![]() Download the full report (PDF)

Download the full report (PDF)

Targeted attacks and malware campaigns

Cha-ching! Skimming off the cream

Earlier in the year, as part of an incident response investigation, we uncovered a new version of the Skimer ATM malware. The malware, which first surfaced in 2009, has been re-designed. So too have the tactics of the cybercriminals using it. The new ATM infector has been targeting ATMs around the world, including the UAE, France, the United States, Russia, Macau, China, the Philippines, Spain, Germany, Georgia, Poland, Brazil and the Czech Republic.

Rather than the well-established method of fitting a fake card-reader to the ATM, the attackers take control over the whole ATM. They start by installing the Skimer malware on the ATM – either through physical access or by compromising the bank’s internal network. The malware infects the ATM’s core – the part of the device responsible for interaction with the wider bank infrastructure, card processing and dispensing of cash. In contrast to a traditional card skimmer, there are no physical signs that the ATM is infected, leaving the attackers free to capture data from cards used at the ATM (including a customer’s bank account number and PIN) or steal cash directly.

The cybercriminal ‘wakes up’ the infected ATM by inserting a card that contains specific records on the magnetic stripe. After reading the card, Skimer is able execute a hard-coded command, or receive commands through a special menu activated by the card. The Skimer user interface appears on the display only after the card is ejected and only if the cybercriminal enters the correct session key within 60 seconds. The menu offers 21 different options, including dispensing money, collecting details of cards that have been inserted in the ATM, self-deletion and performing updates. The cybercriminal can save card details on the chip of their card, or print the details it has collected.

The attackers are careful to avoid attracting attention. Rather than take money directly from the ATM – which would be noticed immediately – they wait (sometimes for several months) before taking action. In most cases, they collect data from skimmed cards in order to create cloned cards later. They use the cloned cards in other, non-infected ATMs, casually withdrawing money from the accounts of the victims in a way that can’t be linked back to the compromised ATM.

Kaspersky Lab has several recommendations to help banks protect themselves. They should carry out regular anti-virus scans; employ allowlisting technologies; apply a good device management policy; make use of full disk encryption; password protect the BIOS of ATMs; enforce hard disk booting and isolate the ATM network from the rest of the bank infrastructure. The magnetic strip of the card used by the cybercriminals to activate the malware contains nine hard-coded numbers. Banks may be able to proactively look for these numbers within their processing systems: so we have shared this information, along with other Indicators of Compromise (IoCs).

In April, one of our experts provided an in-depth examination of ATM jackpotting and offered some insights into what should be done to secure these devices.

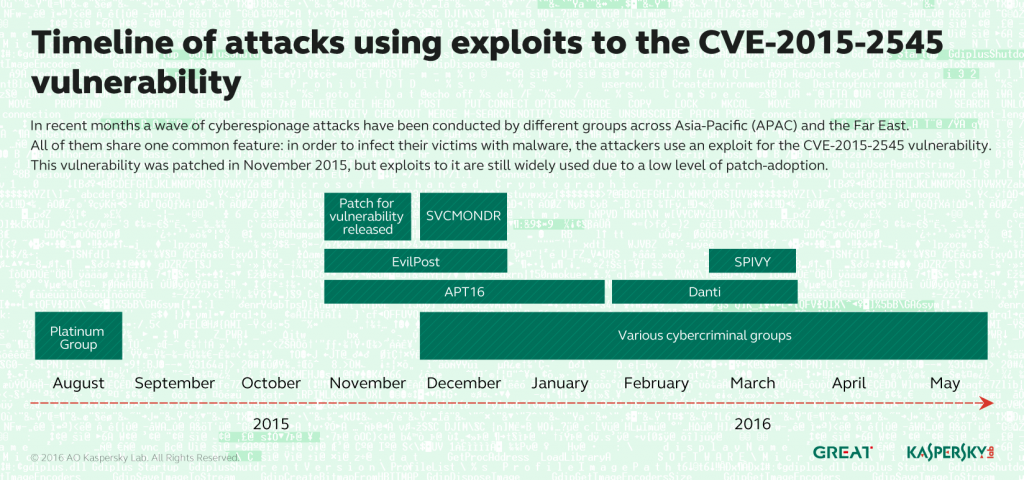

New attacks, old exploit

In recent months we have been tracking a wave of cyber-espionage attacks conducted by different APT groups across the Asia-Pacific and Far East regions. They all share one common feature: they exploit the CVE-2015-2545 vulnerability. This flaw enables an attacker to execute arbitrary code using a specially crafted EPS image file. It uses PostScript and can evade the Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) and Data Execution Prevention (DEP) protection methods built into Windows. The Platinum, APT16, EvilPost and SPIVY groups were already known to use this exploit. More recently, it has also been used by the Danti group.

Danti, first identified in February 2016 and still active, is highly focused on diplomatic bodies. The group predominantly targets Indian government organizations, but data from the Kaspersky Security Network (KSN) indicates that it has also infected targets in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Myanmar, Nepal and the Philippines.

The exploit is delivered using spear-phishing e-mails spoofed to look as though they have been sent by high-ranking Indian government officials. When the victim clicks on the attached DOCX file, the Danti backdoor is installed, allowing the attackers to capture sensitive data.

The origin of the Danti group is unclear, but we suspect that it might be connected to the NetTraveler and DragonOK groups: it’s thought that Chinese-speaking hackers are behind these attacks.

Kaspersky Las has also seen another campaign that makes use of the CVE-2015-2545 vulnerability: we’ve called this SVCMONDR after the Trojan that is downloaded once the attackers get a foothold in the victim’s computer. This Trojan is different to the one used by the Danti group, but it shares some common features with Danti and with APT16 – the latter is a cyber-espionage group believed to be of Chinese origin.

One of the most striking aspects of these attacks is that they are successfully making use of a vulnerability that was patched by Microsoft in September 2015. In November, we predicted that APT campaigns would invest less effort in developing sophisticated tools and make greater use of off-the-shelf malware to achieve their goals. This is a case in point: using a known vulnerability, rather than developing a zero-day exploit. This underlines the need for companies to pay more attention to patch management to secure their IT infrastructure.

New attack, new exploit

Of course, there will always be APT groups that seek to take advantage of zero-day exploits. In June, we reported on a cyber-espionage campaign – code-named ‘Operation Daybreak‘ and launched by a group named ScarCruft – that uses a previously unknown Adobe Flash Player exploit (CVE-2016-1010). This group is relatively new and has so far managed to stay under the radar. We think the group might have previously deployed another zero-day exploit (CVE-2016-0147) that was patched in April.

The group have targeted a range of organizations in Russia, Nepal, South Korea, China, India, Kuwait and Romania. These include an Asian law enforcement agency, one of the world’s largest trading companies, a mobile advertising and app monetization company in the United States, individuals linked to the International Association of Athletics Federations and a restaurant located in one of Dubai’s top shopping centres. The attacks started in March 2016: since some of them are very recent, we believe that the group is still active.

The exact method used to infect victims is unclear, but we think that the attackers use spear-phishing e-mails that point to a hacked website hosting the exploit. The site performs a couple of browser checks before redirecting victims to a server controlled by the hackers in Poland. The exploitation process consists of three Flash objects. The one that triggers the vulnerability in Adobe Flash Player is located in the second SWF file delivered to the victim. At the end of the exploitation chain, the server sends a legitimate PDF file, called ‘china.pdf’, to the victim: this seems to be written in Korean.

In Q2 2016, @kaspersky #mobile security products detected 3.6M malicious installation packages #KLreport

Tweet

The attackers use a number of interesting methods to evade detection, including exploiting a bug in the Windows Dynamic Data Exchange (DDE) component in order to bypass security solutions – a method not seen before. This flaw has been reported to Microsoft.

Flash Player exploits are becoming rare, because in most cases they need to be coupled with a sandbox bypass exploit – this makes them tricky to do. Moreover, although Adobe is planning to drop Flash support soon, it continues to implement new mitigations to make exploitation of Flash Player increasingly difficult. Nevertheless, resourceful groups such as ScarCruft will continue to try and find zero-day exploits to target high-profile victims.

While there’s no such thing as 100 per cent security, the key is to increase security defences to the point that it becomes so expensive for an attacker to breach them that they give up or choose an alternative target. The best defence against targeted attacks is a multi-layered approach that combines traditional anti-virus technologies with patch management, host-based intrusion prevention and a default-deny allowlisting strategy. According to a study by the Australian Signals Directorate, 85 per cent of targeted attacks analysed could have been stopped by employing four simple mitigation strategies: application allowlisting, updating applications, updating operating systems and restricting administrative privileges.

Kaspersky Lab products detect the Flash exploit as ‘HEUR:Exploit.SWF.Agent.gen’. The attack is also blocked proactively by our Automatic Exploit Prevention (AEP) component. The payloads are detected as ‘HEUR:Trojan.Win32.ScarCruft.gen’.

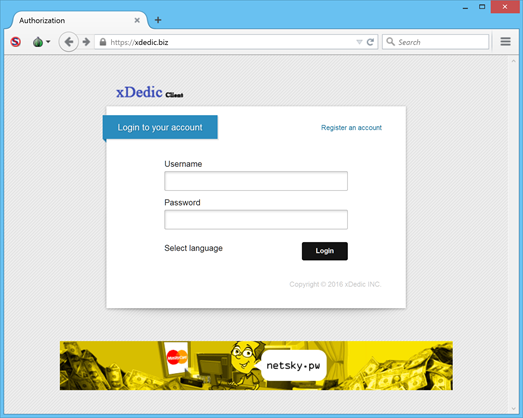

XDedic: APT-as-a-Service

Kaspersky Lab recently investigated an active cybercriminal trading platform called xDedic, an online black market for hacked server credentials around the world – all available through the Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP). We initially thought that this market extended to 70,000 servers, but new data suggests that the XDedic market is much wider – including credentials for 176,000 servers. XDedic includes a search engine, enabling potential buyers to find almost anything – from government and corporate networks – for as little as $8 per server. This low price provides ‘customers’ with access to data on such servers and their use as a bridgehead for further targeted attacks.

The owners of the ‘xdedic[.]biz’ domain claim that they have no relation to those selling access to hacked servers – they are simply selling a secure trading platform for others. The XDedic forum has a separate sub-domain, ‘partner[.]xdedic[.]biz’, for the site’s ‘partners’ – that is, those selling hacked servers. The Xdedic owners have developed a tool that automatically collects information about the system, including websites available, software installed and more. They also provide others tools to its partners, including a patch for RDP servers to support multiple logins for the same user and proxy installers.

The existence of underground markets is not new. But we are seeing a greater level of specialisation. And while the model adopted by the XDedic owners isn’t something that can be replicated easily, we think it’s likely that other specialized markets are likely to appear in the future.

Data from KSN helped us identify several files that were downloaded from the XDedic partner portal: Kaspersky Lab products detect these files as malicious. We have also denylisted the URLs of control servers used for gathering information about the infected systems. Our detailed report on XDedic contains more information on hosts and network-based IoCs.

Lurking around the Russian Internet

Sometimes our researchers find malware that is particular about where it infects. On the closed message boards used by Russian cybercriminals, for example, you sometimes see the advice ‘Don’t work with RU’ – offered by experienced criminals to the younger generation: i.e. don’t infect Russian computers, don’t steal money from Russians and don’t use them to launder money. There are two good reasons for this. First, online banking is not as common as it is in the west. Second, victims outside Russia are unlikely to lodge a complaint with the Russian police – assuming, of course, that they even know that Russian cybercriminals are behind the malware that has infected them.

But there are exceptions to every rule. One of these is the Lurk banking Trojan that has been used to steal money from victims in Russia for several years. The cybercriminals behind Lurk are interested in telecommunications companies, mass media and news aggregators and financial institutions. The first provide them with the means to transfer traffic to the attackers’ servers. The news sites provide them with a way to infect a large number of victims in their ‘target audience’ – i.e. the financial sector. The Trojan’s targets appear to include Russia’s four largest banks.

The primary method used to spread the Lurk Trojan is drive-by download, using the Angler exploit pack: the attackers place a link on compromised websites that leads to a landing page containing the exploit. Exploits (including zero-days) are typically implemented in Angler before being used in other exploit packs, making it particularly dangerous. The attackers also distribute code through legitimate websites, where infected files are served to visitors from the .RU zone, but others receive clean files. The attackers use one infected computer in a corporate network as a bridgehead to spread across the organization. They use the legitimate PsExec utility to distribute the malware to other computers; and then use a mini-dropper to execute the Trojan’s main module on the additional computers.

In Q2 2016, @kaspersky #mobile security products detected 83,048 mobile #ransomware Trojans #KLreport

Tweet

There are a number of interesting features of the Lurk Trojan. One distinct feature, that we discussed soon after it first appeared, is that it is ‘file-less’ malware, i.e. it exists only in RAM and doesn’t write its code to the hard drive.

The Trojan is also set apart because it is highly targeted. The authors do their best to ensure that they infect victims that are of interest to them without catching the attention of analysts or researchers. The incidents known to us suggest Lurk is successful at what it was designed for: we regularly receive reports of thefts from online banking systems; and forensic investigations after the incidents reveal traces of Lurk on the affected computers.

Malware stories

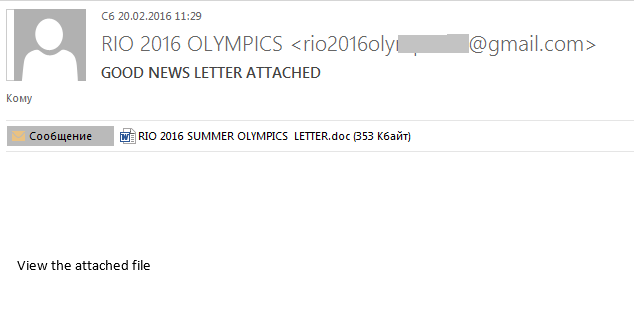

Cybercriminals get ready for Rio

Fraudsters are always on the lookout for opportunities to make money off the back of major sporting events, so it’s no surprise that we’ve seen an increase in cybercriminal activity related to the forthcoming Olympic Games in Brazil.

We’ve seen an increase in spam e-mails. The spammers try to cash in on people’s desire to watch the games live, sending out messages informing the recipient that they have won a (fake) lottery (supposedly organized by the International Olympic Committee and the Brazilian government): all they need to do to claim their tickets is to reply to the e-mail and provide some personal details.

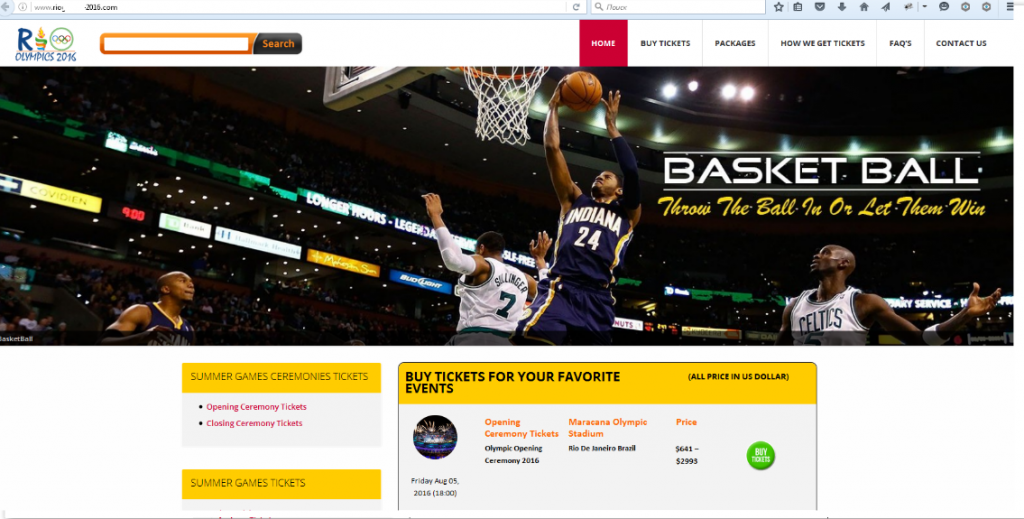

Some messages point to fake websites, like this one offering direct sale of tickets without the need to make an application to the official lottery:

These fake ticketing sites are very convincing. Some fraudsters go the extra mile by obtaining legitimate SSL certificates to provide a secure connection between the victim’s browser and the site – displaying ‘https’ in the browser address bar to lure victims into a false sense of security. The scammers inform their victims that they will receive their tickets two or three weeks before the event, so the victim doesn’t become suspicious until it’s too late and their card details have been used by the cybercriminals. Kaspersky Lab is constantly detecting and blocking new malicious domains, many of which include ‘rio’ or ‘rio2016’ in the title.

It’s too late to buy tickets through official channels, so the best way to see the games is to watch on TV or online. We advise everyone to beware of malicious streaming websites – probably the last-ditch attempt by cybercriminals to scam people out of their money.

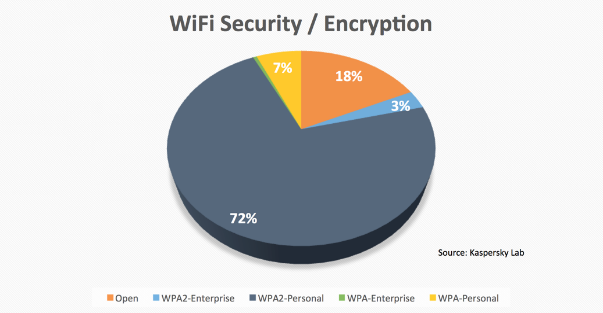

Cybercriminals also take advantage of our desire to stay connected wherever we go – to share our pictures, to update our social network accounts, to find out the latest news or to locate the best places to eat, shop or stay. Unfortunately, mobile roaming charges can be very high, so often people look for the nearest Wi-Fi access point. This is dangerous, because data sent and received over an open Wi-Fi network can be intercepted. So passwords, PINs and other sensitive data can be stolen easily. On top of this, cybercriminals also install fake access points, configured to direct all traffic through a host that can be used to control it – even functioning as a ‘man-in-the-middle’ device that is able to intercept and read encrypted traffic.

To gauge the extent of the problem, we drove by three major Rio 2016 locations and passively monitored the available Wi-Fi networks that visitors are most likely to try and use during their stay – the Brazilian Olympic Committee building, the Olympic Park and the Maracana, Maracanazinho and Engenhao stadiums. We were able to find around 4,500 unique access points. Most are suitable for multimedia streaming. But around a quarter of them are configured with weak encryption protocols: this means that attackers can use them to sniff the data of unsuspecting visitors that connect to them.

To reduce your exposure, we would recommend any traveller (not just those who plan to visit Rio!) to use a VPN connection, so that data from your device travels to the Internet through an encrypted data channel. Be careful though. Some VPNs are vulnerable to DNS leak attacks – meaning that, although your immediate sensitive data is sent via the VPN, your DNS requests are sent in plain text to the DNS servers set by the access point hardware. This would allow an attacker to see what you’re browsing and, if they have access to the compromised Wi-Fi network, define malicious DNS servers – i.e. letting them redirect you from a legitimate site (your bank, for example) to a malicious site. If your VPN provider doesn’t support its own DNS servers, consider an alternative provider or a DNSCrypt service.

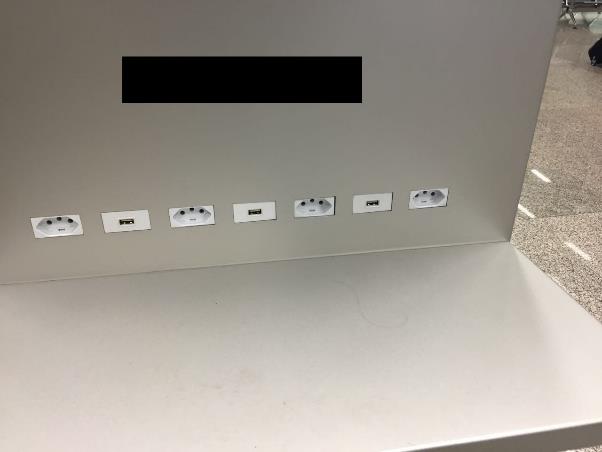

There’s one other thing that we need if we want to stay connected – electricity: we need to keep our mobile devices charged. Today you can find charging-points in shopping centres, airports and even taxis. Typically they provide connectors for leading phone models, as well as a USB connector that a visitor can use with their own cable. Some also provide a traditional power supply that can be used with a phone charger.

But remember that you don’t know what’s connected to the other end of the USB connector. If an attacker compromises the charging-point, they can execute commands that allow them to obtain information about your device, including the model, IMEI number, phone number and more: information they can use to run a device-specific attack that would then enable them to infect the device. You can find more information about the data that’s transmitted when you connect a device using USB and how an attacker could use it to compromise a mobile device.

This doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t charge your device when you’re away from home. But you should take steps to protect yourself. It’s always best to use your own charger, rather than using charging cables at a public charging-point or buying one from an unknown source. You should also use a power outlet, instead of a USB socket.

Cybercriminals also continue to exploit established ways to make money. This includes using ATM skimmers to steal credit card data. The most basic skimmers install a card reader and a camera to record the victim’s PIN. The best way to protect yourself from this is to cover the keypad as you enter your PIN. However, sometimes cybercriminals replace the whole ATM, including the keypad and screen, in which case the typed password is stored on the fake ATM system. So it’s also important to check the ATM before you insert your card. Check to see if the green light on the card reader is on: typically, they replace the card reader with a version where there is no light, or it’s switched off. Also check the machine to see if there is anything suspicious, such as missing or broken parts.

Card cloning is another problem facing visitors to Rio 2016. While chip-and-PIN makes life harder for cybercriminals, it’s possible for them to exploit flaws in the EMV transaction implementation. It’s difficult to protect yourself against this type of attack, because usually the point-of-sale is modified in order to save the data – to be collected later by the cybercriminals. Sometimes they don’t need physical access to extract the stolen data, as they collect it via Bluetooth. However, there are some steps you can take to reduce your exposure to this type of attack. Sign up for SMS notifications of card transactions from your bank, if they provide this service. Never give your card to the retailer: if they can’t bring the machine to you, go to the machine. If the device looks suspicious, use a different payment method. Before typing your PIN, make sure you’re on the card payment screen and ensure that your PIN isn’t going to be displayed on the screen.

Ransomware: backup or pay up?

Towards the end of last year, we predicted that ransomware would gain ground on banking Trojans – for the attackers, ransomware is easily monetized and involves a low cost per victim. So it’s no surprise that ransomware attacks are increasing. Kaspersky Lab products blocked 2,315,931 ransomware attacks between April 2015 and April 2016 – that’s an increase of 17.7 per cent on the previous year. The number of cryptors (as distinct from blockers) increased from 131,111 in 2014-15 to 718,536 in 2015-16. Last year, 31.6 per cent of all ransomware attacks were cryptors. You can find further information, including an overview of the development of ransomware, in our KSN Report: PC ransomware in 2014-16.

Most ransomware attacks are directed at consumers – 6.8 per cent of attacks in 2014-15 and 13.13 percent in 2015-16 targeted the corporate sector.

However, the figures are different for cryptors: throughout the 24 months covered by the report, around 20 per cent of cryptor attacks targeted the corporate sector.

Hardly a month goes by without reports of ransomware attacks in the media – including recent reports of a hospital and online casino falling victim to ransomware attacks. Yet while public awareness of the problem is growing, it’s clear that consumers and organizations alike are not doing enough to combat the threat; and cybercriminals are capitalizing on this – this is clearly reflected in the number of attacks we’re seeing.

It’s important to reduce your exposure to ransomware (and we’ve outlined important steps you can take here and here). However, there’s no such thing as 100 per cent security, so it’s also important to mitigate the risk. In particular, it’s vital to ensure that you have a backup, to avoid facing a situation where the only choices are to pay the cybercriminals or lose your data. It’s never advisable to pay the ransom. Not only does this validate the cybercriminals’ business model, but there’s no guarantee that they will decrypt your data once you’ve paid them – as one organization discovered recently to its cost. If you do find yourself in a situation where your files are encrypted and you don’t have a backup, ask if your anti-malware vendor is able to help. Kaspersky Lab, for example, is able to help recover data encrypted by some ransomware.

Mobile malware

Displaying adverts remains one of the main methods of monetization for detected mobile objects. Trojan.AndroidOS.Iop.c became the most popular mobile Trojan in Q2 2016, accounting for more than 10% of all detected mobile malware encountered by our users during the reporting period. It displays adverts and installs, usually secretly, various programs using superuser privileges. Such activity quickly renders the infected device virtually unusable due to the amount of adverts and new applications on it. Because this Trojan can gain superuser privileges, it is very difficult to delete the programs that it installs.

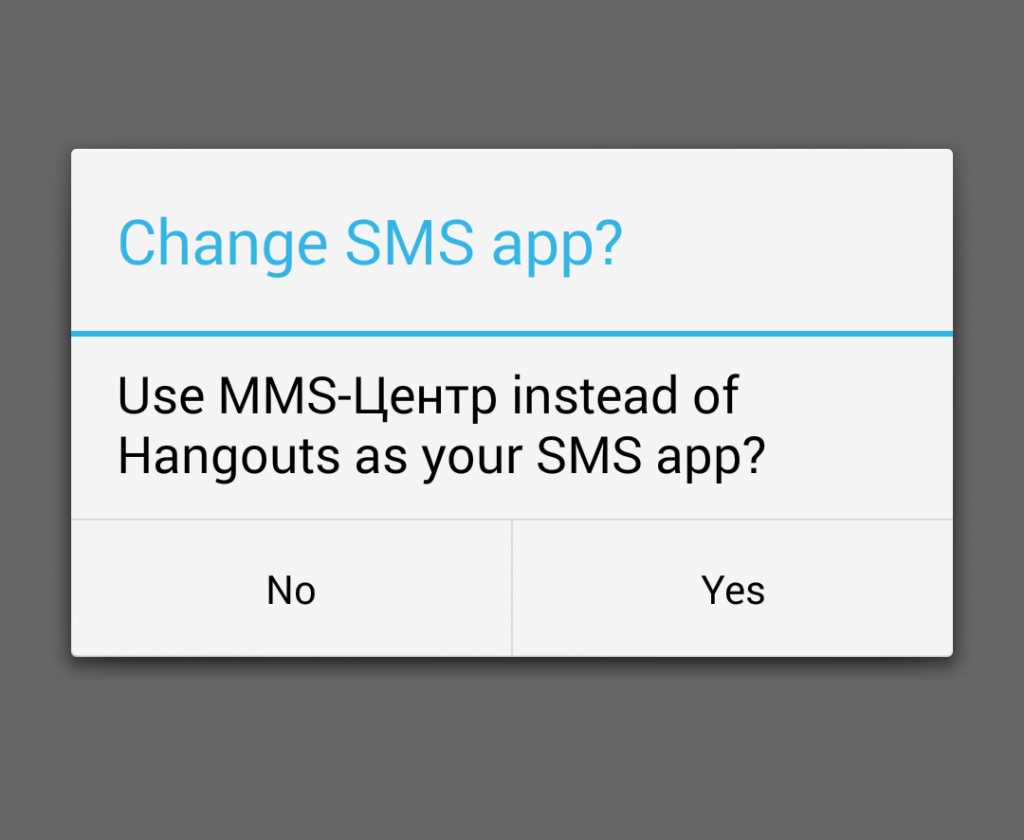

In our report IT threat evolution in Q1 2016 we wrote about the Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Asacub family of banking malware. Representatives of this family have an unusual technique for bypassing the security mechanisms used by operating systems – they overlay the regular system window requesting device administrator privileges with their own window containing buttons. The Trojan thereby conceals the fact that it is gaining elevated privileges in the system, and tricks the user into approving these privileges. In Q2 2016, Asacub introduced yet another method for deceiving users: the Trojan acquired SMS messenger functionality and started offering its services in place of the device’s standard SMS app.

Dialog window of Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Asacub.i asking for the rights to be the main SMS application

This allows the Trojan to bypass system constraints first introduced in Android 4.4 as well as delete or hide incoming SMSs from the user.

Back in October 2015, we wrote about representatives of the Trojan-PSW.AndroidOS.MyVk family that steal passwords from user accounts on the VK.com social network. This quarter, those responsible for distributing Trojans from this family introduced a new approach for bypassing Google Play security mechanisms that involved first publishing an app containing useful functionality with no malicious code. Then, at least once, they updated it with a new version of the application – still without any malicious code. It was more than a month after the initial publication that the attackers eventually added malicious code to an update. As a result, thousands of users downloaded Trojan-PSW.AndroidOS.MyVk.i.

Data breaches

Personal information is a valuable commodity, so it’s no surprise that cybercriminals target online providers, looking for ways to bulk-steal data in a single attack. We’ve become accustomed to the steady stream of security breaches reported in the media. This quarter has been no exception, with reported attacks on beautifulpeople.com, the nulled.io hacker forum (underlining the fact that it’s not just legitimate systems that are targeted), kiddicare, Tumblr and others.

Some of these attacks resulted in the theft of huge amounts of data, highlighting the fact that many companies are failing to take adequate steps to defend themselves. It’s not simply a matter of defending the corporate perimeter. There’s no such thing as 100 per cent security, so it’s not possible to guarantee that systems can’t be breached. But any organization that holds personal data has a duty of care to secure it effectively. This includes hashing and salting customer passwords and encrypting other sensitive data.

Consumers can limit the damage of a security breach at an online provider by ensuring that they choose passwords that are unique and complex: an ideal password is at least 15 characters long and consists of a mixture of letters, numbers and symbols from the entire keyboard. As an alternative, people can use a password manager application to handle all this for them automatically. Unfortunately, all too often people use easy-to-guess passwords and re-use the same password for multiple online accounts – so that if the password for one is compromised, all the victim’s online IDs are vulnerable. This issue was highlighted publicly in May 2016 when a hacker known as ‘Peace’ attempted to sell 117 million LinkedIn e-mails and passwords that had been stolen some years earlier. More than one million of the stolen passwords were ‘123456’!

Many online providers offer two-factor authentication – i.e. requiring customers to enter a code generated by a hardware token, or one sent to a mobile device, in order to access a site, or at least in order to make changes to account settings. Two-factor authentication certainly enhances security – if people choose to take advantage of it.

Several companies are hoping to replace passwords altogether. Apple allows fingerprint authorization for iTunes purchases and payments using Apple Pay. Samsung has said it will introduce fingerprint, voice and iris recognition for Samsung Pay. Amazon has announced ‘selfie-pay’. MasterCard and HSBC have announced the introduction of facial and voice recognition to authorize transactions. The chief benefit, of course, is that it replaces something that customers have to remember (a password) with something they have – with no opportunity to short-circuit the process (as they do when they choose a weak password).

Biometrics are seen by many as the way forward. However, they are not a security panacea. Biometrics can be spoofed, as we’ve discussed before (here, here and here); and biometric data can be stolen. In the end, multi-factor authentication is essential – combining something you know, something you have and something you are.

IT threat evolution in Q2 2016. Overview