Targeted attacks and malware campaigns

Lazarus targets cryptocurrency exchange

Lazarus is a well-established threat actor that has conducted cyber-espionage and cybersabotage campaigns since at least 2009. In recent years, the group has launched campaigns against financial organizations around the globe. In August we reported that the group had successfully compromised several banks and infiltrated a number of global cryptocurrency exchanges and fintech companies. While assisting with an incident response operation, we learned that the victim had been infected with the help of a Trojanized cryptocurrency trading application that had been recommended to the company over email.

An unsuspecting employee had downloaded a third-party application from a legitimate looking website, infecting their computer with malware known as Fallchill, an old tool that Lazarus has recently started using again.

It seems as though Lazarus has found an elaborate way to create a legitimate looking site and inject a malicious payload into a ‘legitimate looking’ software update mechanism – in this case, creating a fake supply chain rather than compromising a real one. At any rate, the success of the Lazarus group in compromising supply chains suggests that it will continue to exploit this method of attack.

The attackers went the extra mile and developed malware for non-Windows platforms – they included a Mac OS version and the website suggests that a Linux version is coming soon. This is probably the first time that we’ve seen this APT group using malware for Mac OS. It would seem that in the chase after advanced users, software developers from supply chains and some high-profile targets, threat actors are forced to develop Mac OS malware tools. The fact that the Lazarus group has expanded its list of targeted operating systems should be a wake-up call for users of non-Windows platforms.

This campaign should be a lesson to all of us and a warning to businesses relying on third-party software. Do not automatically trust the code running on your systems. Neither a good-looking website, nor a solid company profile, nor digital certificates guarantee the absence of backdoors. Trust has to be earned and proven.

You can read our Operation AppleJeus report here.

LuckyMouse

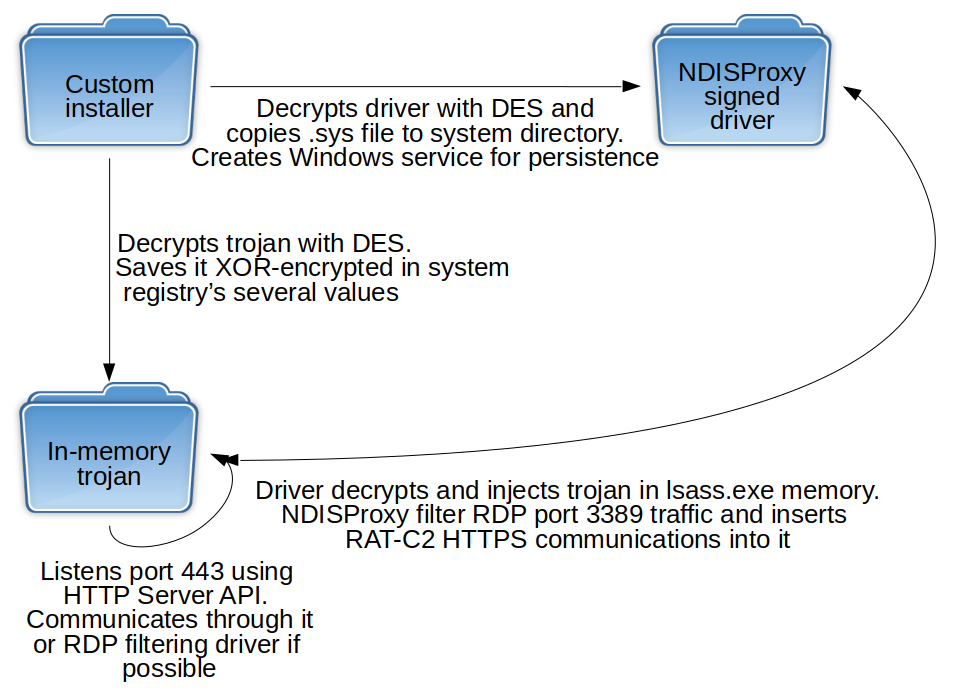

Since March 2018, we have found several infections where a previously unknown Trojan was injected into the ‘lsass.exe’ system process memory. These implants were injected by the digitally signed 32- and 64-bit network filtering driver NDISProxy. Interestingly, this driver is signed with a digital certificate that belongs to the Chinese company LeagSoft, a developer of information security software based in Shenzhen, Guangdong. We informed the company about the issue via CN-CERT.

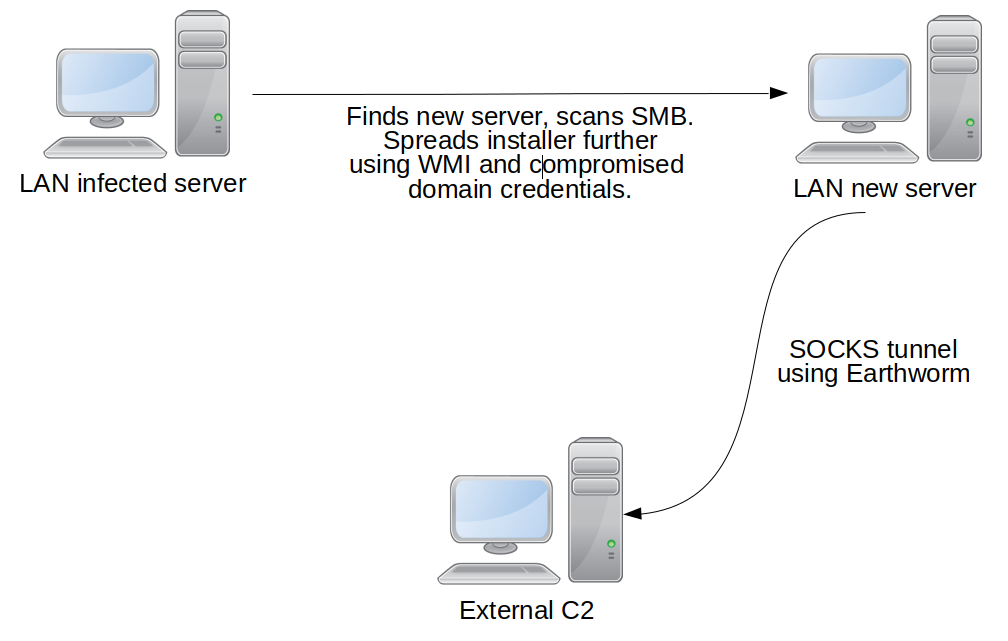

The campaign targeted Central Asian government organizations and we believe the attack was linked to a high-level meeting in the region. We believe that the Chinese-speaking threat actor LuckyMouse is responsible for this campaign. The choice of the Earthworm tunneler used in the attack is typical for Chinese-speaking actors. Also, one of the commands used by the attackers (“-s rssocks -d 103.75.190[.]28 -e 443”) creates a tunnel to a previously known LuckyMouse command-and-control (C2) server. The choice of victims in this campaign also aligns with the previous interests shown by this threat actor.

The malware consists of three modules: a custom C++ installer, the NDISProxy network filtering driver and a C++ Trojan:

We have not seen any indications of spear phishing or watering hole activity. We think the attackers spread their infectors through networks that were already compromised.

The Trojan is a full-featured RAT capable of executing common tasks such as command execution, and downloading and uploading files. The attackers use it to gather a target’s data, make lateral movements and create SOCKS tunnels to their C2 using the Earthworm tunneler. This tool is publicly available and is popular among Chinese-speaking actors. Given that the Trojan is an HTTPS server itself, we believe that the SOCKS tunnel is used for targets without an external IP, so that the C2 is able to send commands.

You can read our LuckyMouse report here.

Financial fraud on an industrial scale

Usually, attacks on industrial enterprises are associated with cyber-espionage or sabotage. However, we recently discovered a phishing campaign designed to steal money from such organizations – primarily manufacturing companies.

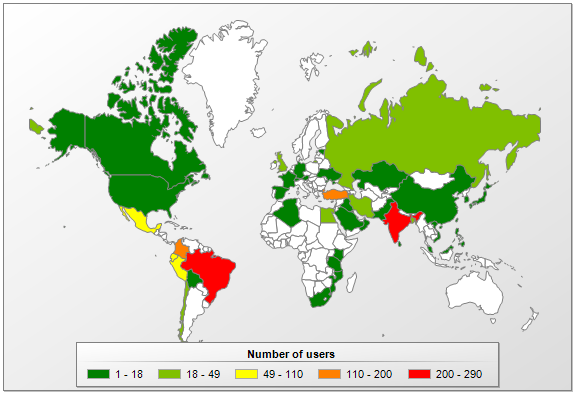

The attackers use standard phishing techniques to lure their victims into clicking on infected attachments, using emails disguised as commercial offers and other financial documents. The criminals use legitimate remote administration applications – either TeamViewer or RMS (Remote Manipulator System). These programs were employed to gain access to the device, then scan for information on current purchases, and financial and accounting software. The attackers then use different ploys to steal company money – for example, by replacing the banking details in transactions. At the time we published our report, on August 1, we had seen infections on around 800 computers, spread across at least 400 organizations in a wide array of industries – including manufacturing, oil and gas, metallurgy, engineering, energy, construction, mining and logistics. The campaign has been ongoing since October 2017.

Our research highlights that even when threat actors use simple techniques and known malware they can successfully attack industrial companies by using social engineering tricks and hiding their code in target systems – using legitimate remote administration software to evade detection by antivirus solutions. Remote administration capabilities give criminals full control of compromised systems, so possible attack scenarios are not limited to the theft of money. In the process of attacking their targets, the attackers steal sensitive data belonging to target organizations, their partners and customers, carry out surreptitious video surveillance of company employees and record audio and video using devices connected to infected machines. While the series of attacks targets primarily Russian organizations, the same tactics and tools could be successfully used in attacks against industrial companies anywhere.

You can find out more about how attackers use remote administration tools to compromise their targets here, and an overview of attacks on ICS systems in the first half of 2018 here.

Malware stories

Exploiting the digital gold rush

For some time now, we’ve been tracking a dramatic decline in ransomware and a massive growth in cryptocurrency mining. The number of people who encountered miners grew from 1,899,236 in 2016-17 to 2,735,611 in 2017-18. This is clearly because it’s a lucrative activity for cybercriminals – we estimate that mining botnets generated more than $7,000,000 in the second half of 2017. Not only are we seeing purpose-built cryptocurrency miners, we’re also seeing existing malware adding this functionality to their arsenal.

The ransomware Trojan Rakhni is a case in point. The malware loader chooses which component to install depending on the device. The malware, which we have seen in Russia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, Germany and India, is distributed through spam mailings with malicious attachments. One of the samples we analysed masquerades as a financial document. When loaded, this appears to be a document viewer. The malware displays an error message explaining why nothing has opened. It then disables Windows Defender and installs forged digital certificates.

The malware checks to see if there are Bitcoin-related folders on the computer. If there are, it encrypts files and demands a ransom. If not, it installs a cryptocurrency miner. Finally, the malware tries to spread to other computers within the network. You can read our analysis of Rakhni here.

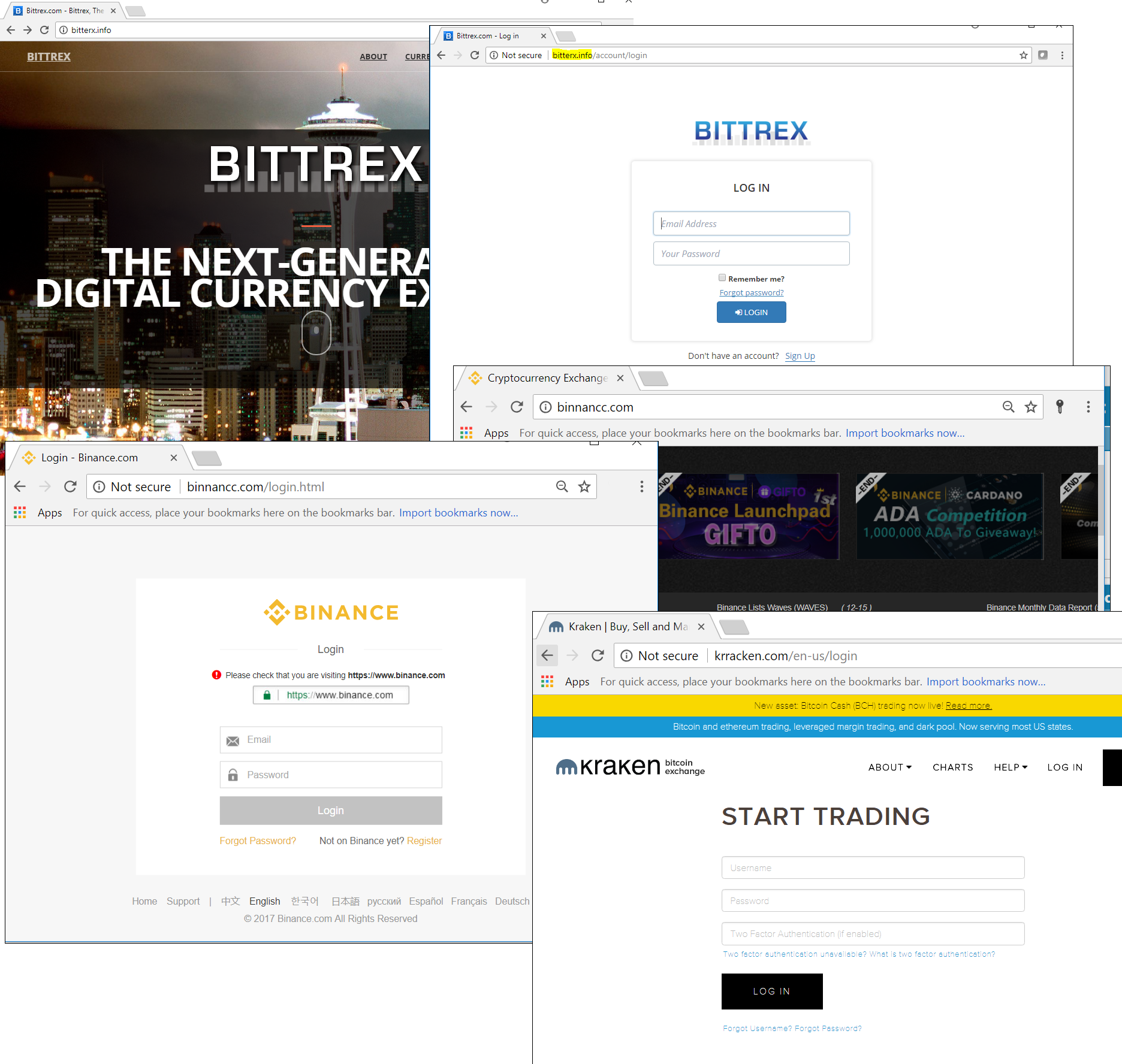

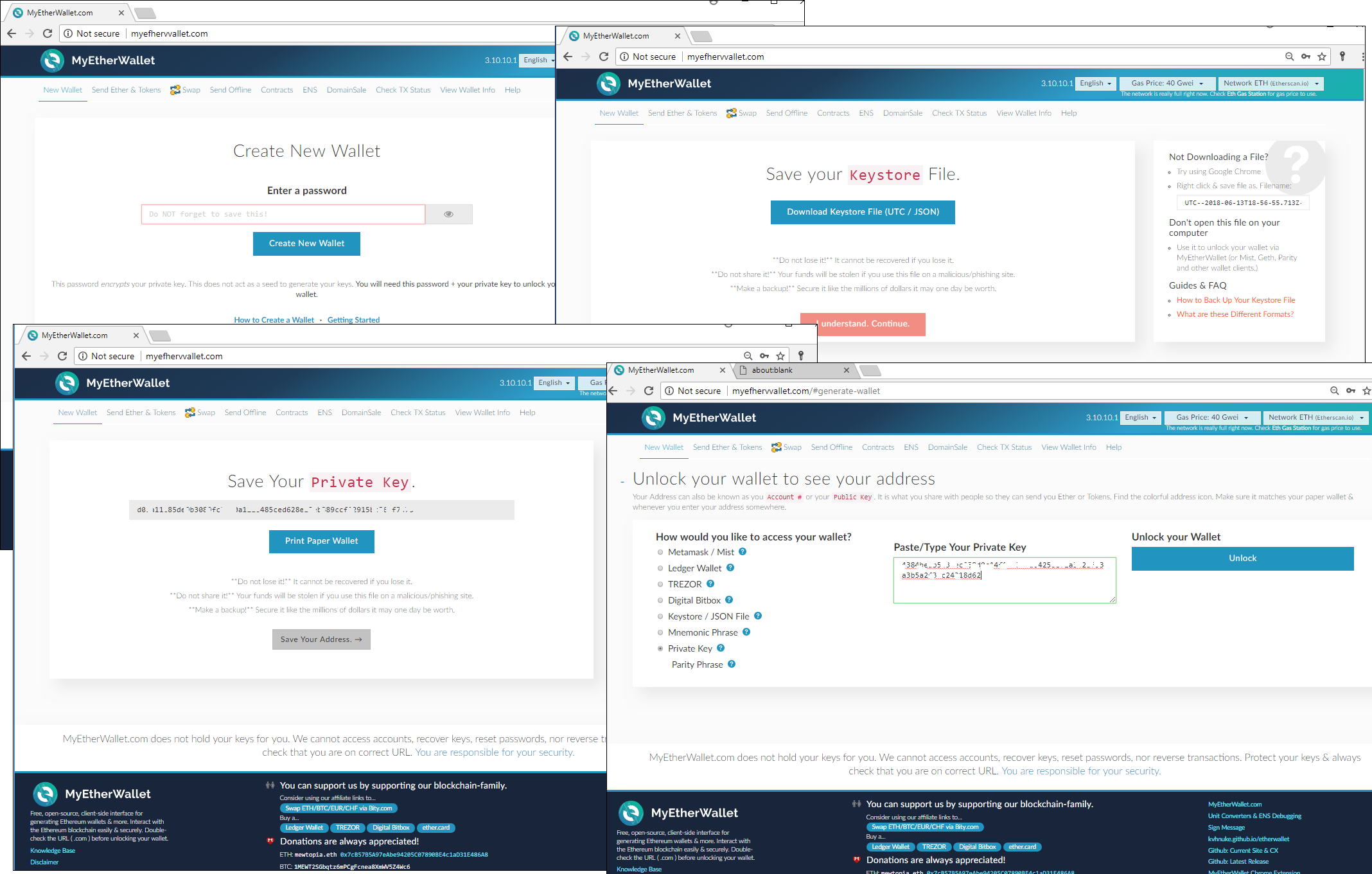

Cybercriminals don’t just use malware to cash in on the growing interest in cryptocurrencies; they also use established social engineering techniques to trick people out of their digital money. This includes sending links to phishing scams that mimic the authorization pages of popular crypto exchanges, to trick their victims into giving the scammers access to their crypto exchange account – and their money. In the first half of 2018, we saw 100,000 of these attempts to redirect people to such fake pages.

The same approach is used to gain access to online wallets, where the ‘hook’ is a warning that the victim will lose money if they don’t go through a formal identification process – the attackers, of course, harvest the details entered by the victim. This method works just as well where the victim is using an offline wallet stored on their computer.

Scammers also try to use the speculation around cryptocurrencies to trick people who don’t have a wallet: they lure them to fake crypto wallet sites, promising registration bonuses, including cryptocurrency. In some cases, they harvest personal data and redirect the victim to a legitimate site. In others, they open a real wallet for the victim, which is compromised from the outset. Online wallets and exchanges aren’t the only focus of the scammers; we have also seen spoof versions of services designed to facilitate transactions with digital coins stored on the victim’s computer.

Earlier this year, we provided some advice on choosing a crypto wallet.

We recently discovered a cryptocurrency miner, named PowerGhost, focused mainly on workstations and servers inside corporate networks – thereby hoping to commandeer the power of multiple processors in one fell swoop. It’s not uncommon to see cybercriminals infect clean software with a malicious miner to promote the spread of their malware. However, the creators of PowerGhost went further, using fileless methods to establish it in a compromised network. PowerGhost tries to log in to network user accounts using WMI (Windows Management Instrumentation), obtaining logins and passwords using the Mimikatz data extraction tool. The malware can also be distributed using the EternalBlue exploit (used last year in the WannaCry and ExPetr outbreaks). Once a device has been infected, PowerGhost tries to enhance its privileges using operating system vulnerabilities. Most of the attacks we’ve seen so far have been in India, Turkey, Brazil and Colombia.

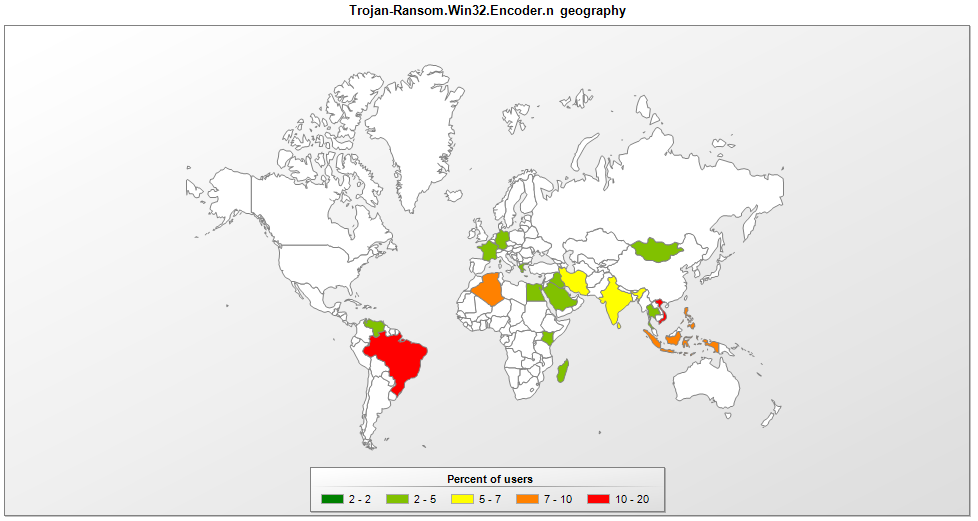

KeyPass ransomware

The number of ransomware attacks has been declining in the last year or so. Nevertheless, this type of malware remains a problem and we continue to see the development of new ransomware families. Early in August, our anti-ransomware module started detecting the ‘KeyPass‘ Trojan. In just two days, we found this malware in more than 20 countries – Brazil and Vietnam were hardest hit, but we also found victims in Europe, Africa and the Far East.

We believe that the criminals behind KeyPass use fake installers that download the malware.

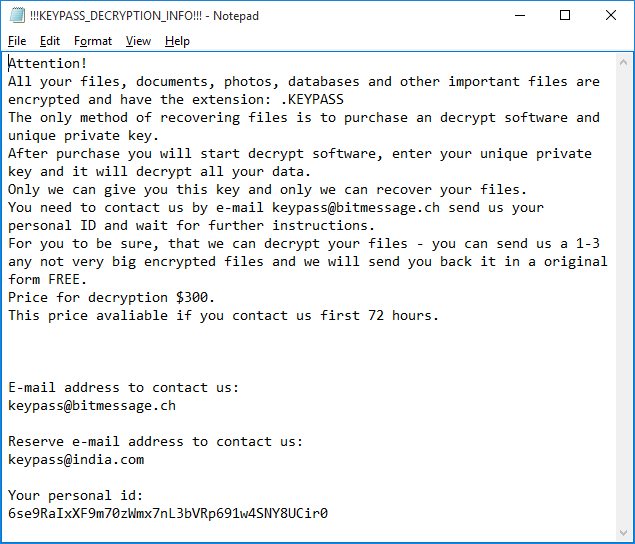

KeyPass encrypts all files, regardless of extension, on local drives and network shares that are accessible from the infected computer. It ignores some files located in directories that are hardcoded in the malware. Encrypted files are given the additional extension ‘KEYPASS’, and ransom notes called ‘!!!KEYPASS_DECRYPTION_INFO!!!.txt’ are saved in each directory containing encrypted files.

The creators of this Trojan implemented a very simplistic scheme. The malware uses the symmetric algorithm AES-256 in CFB mode with zero IV and the same 32-byte key for all files. The Trojan encrypts a maximum of 0x500000 bytes (~5 MB) of data at the start of each file.

Shortly after launch, the malware connects to its C2 server and obtains the encryption key and infection ID for the current victim. The data is transferred over plain HTTP in the JSON format. If the C2 is unavailable – for example, the infected computer is not connected to the internet, or the server is down – the malware uses a hardcoded key and ID. As a result, in the case of offline encryption, decryption of the victim’s files will be trivial.

Probably the most interesting feature of the KeyPass Trojan is its ability to take ‘manual control’. The Trojan contains a form that is hidden by default, but which can be shown after pressing a special button on the keyboard. This form allows the criminals to customize the encryption process by changing such parameters as the encryption key, the name of the ransom note, the text of the ransom, the victim ID, the extension of encrypted files and the list of directories to be excluded from encryption. This capability suggests that the criminals behind the Trojan might intend to use it in manual attacks.

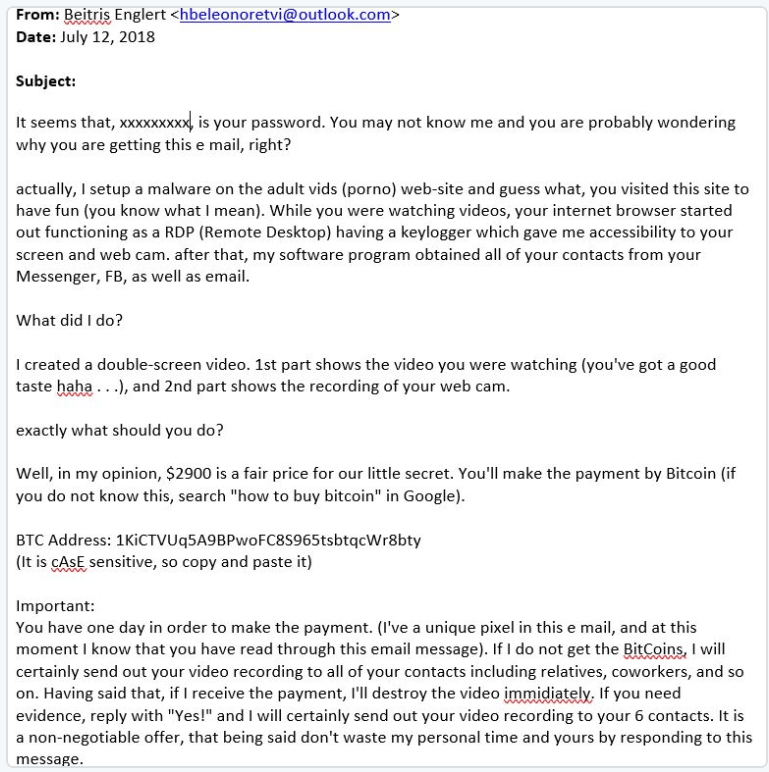

Sextortion with a twist

Scams come in many forms, but the people behind them are always on the lookout for ways to lend credibility to the scam and maximise their opportunity to make money. One recent ‘sextortion’ scam uses stolen passwords for this purpose. The victim receives an email message claiming that their computer has been compromised and that the attacker has recorded a video of them watching pornographic material. The attackers threaten to send a copy of the video to the victim’s contacts unless they pay a ransom within 24 hours. The ransom demand is $1,400, payable in bitcoins.

The scammer includes a legitimate password in the message, in a bid to convince the victim that they have indeed been compromised. It seems that the passwords used are real, although in some cases at least they are very old. The passwords were probably obtained in an underground market and came from an earlier data breach.

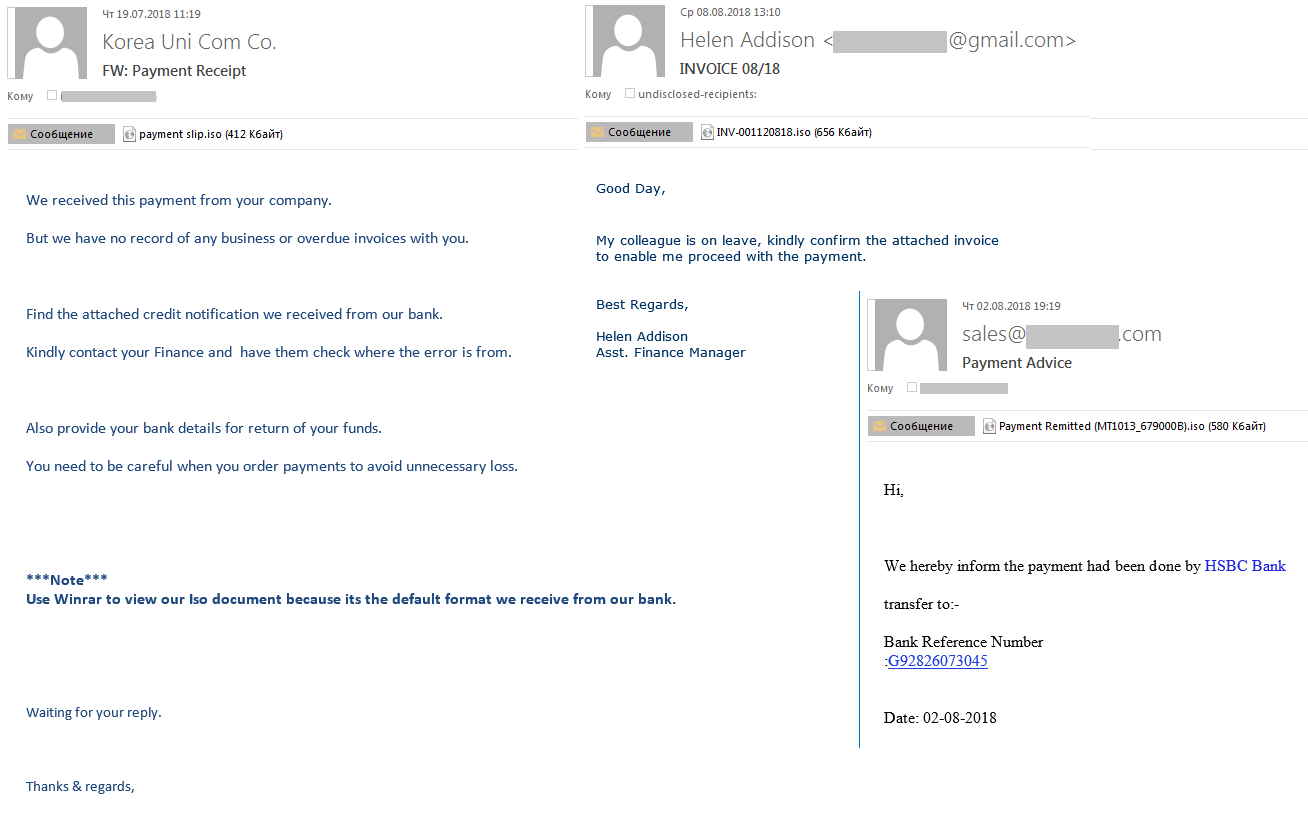

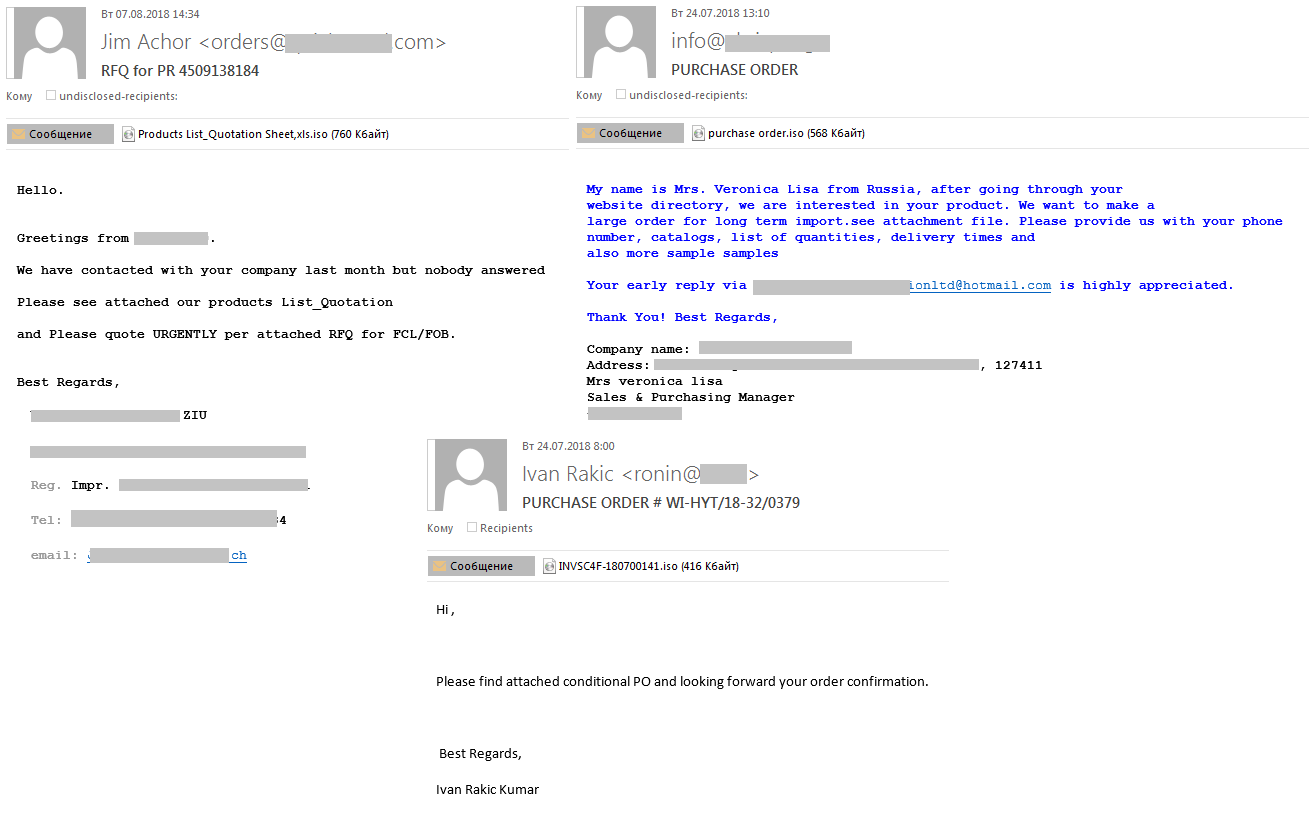

The hunt for corporate passwords

It’s not just individuals who are targeted by phishing attacks – starting from early July, we saw malicious spam activity targeting corporate mailboxes. The messages contained an attachment with an .ISO extension that we detect as Loki Bot. The objective of the malware is to steal passwords from browsers, messaging applications, mail and FTP clients, and cryptocurrency wallets, and then to forward the data to the criminals behind the attacks.

The messages are diverse in nature. They include fake notifications from well-known companies:

Or fake orders or offers:

The scammers pass off malicious files as financial documents: invoices, transfers, payments, etc. This is a fairly popular malicious spamming technique, with the message body usually consisting of no more than a few lines and the subject mentioning the fake attachment.

Each year we see an increase in spam attacks on the corporate sector aimed at obtaining confidential corporate information: intellectual property, authentication data, databases, bank accounts, etc. That’s why it’s essential for corporate security strategy to include both technical protection and staff education – to stop them becoming the entry-point for a cyberattack.

Botnets: the big picture

Spam mailshots with links to malware, and bots downloading other malware, are just two botnet deployment scenarios. The choice of payload is limited only by the imagination of the botnet operator or their customers. It might be ransomware, a banker, a miner, a backdoor, etc. Every day we intercept numerous file download commands sent to bots of various types and families. We recently presented the results of our analysis of botnet activity for H2 2017 and H1 2018.

Here are the main trends that we identified by analyzing the files downloaded by bots:

- The share of miners in bot-distributed files is increasing, as cybercriminals have begun to view botnets as a tool for cryptocurrency mining.

- The number of downloaded droppers is also on the rise, reflecting the fact that attacks are multi-stage and growing in complexity.

- The share of banking Trojans among bot-downloaded files in 2018 decreased, but it’s too soon to speak of an overall reduction in number, since they are often delivered by droppers.

- Increasingly, botnets are leased according to the needs of the customer, so in many cases it is difficult to pinpoint the ‘specialization’ of the botnet.

Using USB devices to spread malware

USB devices, which have been around for almost 20 years, offer an easy and convenient way to store and transfer digital files between computers that are not directly connected to each other or to the internet. This capability has been exploited by cyberthreat actors – most notably in the case of the state-sponsored threat Stuxnet, which used USB devices to inject malware into the network of an Iranian nuclear facility.

These days the use of USB devices as a business tool is declining, and there is greater awareness of the security risks associated with them. Nevertheless, millions of USB devices are still produced for use at home, in businesses and in marketing promotion campaigns such as trade show giveaways. So they remain a target for attackers.

Kaspersky Lab data for 2017 showed that one in four people worldwide were affected by a local cyber-incident, i.e. one not related to the internet. These attacks are detected directly on a victim’s computer and include infections caused by removable media such as USB devices.

We recently published a review of the current cyberthreat landscape for removable media, particularly USBs, and offered advice and recommendations for protecting these little devices and the data they carry.

Here is a summary of our findings.

- USB devices and other removable media have been used to spread cryptocurrency mining software since at least 2015. Some victims were found to have been carrying the infection for years.

- The rate of detection for the most popular bitcoin miner, Trojan.Win64.Miner.all, is growing by around one-sixth year-on-year.

- Every tenth person infected via removable media in 2018 was targeted with this cryptocurrency miner: around 9.22% – up from 6.7% in 2017 and 4.2% in 2016.

- Other malware spread through removable media includes the Windows LNK family of Trojans, which has been among the top three USB threats detected since at least 2016.

- The Stuxnet exploit, CVE-2010-2568, remains one of the top 10 malicious exploits spread via removable media.

- Emerging markets are the most vulnerable to malicious infection spread by removable media – with Asia, Africa and South America among the most affected – but isolated hits were also detected in countries in Europe and North America.

- Dark Tequila, a complex banking malware reported in August 2018 has been claiming consumer and corporate victims in Mexico since at least 2013, with the infection spreading mainly through USB devices.

New trends in the world of IoT threats

The use of smart devices is increasing. Some forecasts suggest that by 2020 the number of smart devices will exceed the world’s population several times over. Yet manufacturers still don’t prioritize security: there are no reminders to change the default password during initial setup or notifications about the release of new firmware versions, and the updating process itself can be complex for the average consumer. This makes IoT devices a prime target for cybercriminals. Easier to infect than PCs, they often play an important role in the home infrastructure: some manage internet traffic, others shoot video footage and still others control domestic devices – for example, air conditioning.

Malware for smart devices is increasing not only in quantity but also quality. More and more exploits are being weaponized by cybercriminals, and infected devices are used to launch DDoS attacks, to steal personal data and to mine cryptocurrency.

You can read our report on IoT threats here, including tips on how to reduce the risk of smart devices being infected.

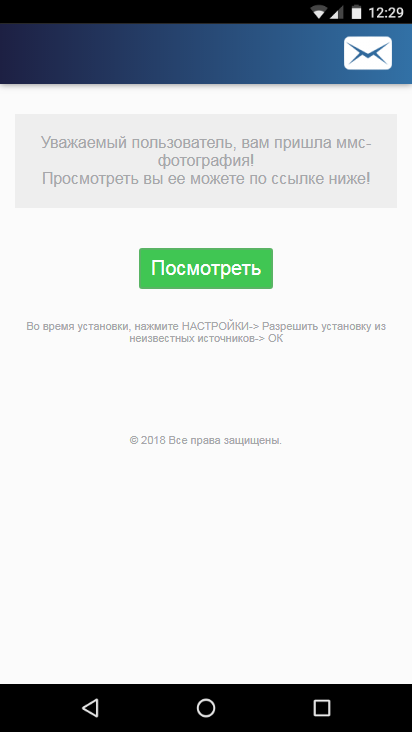

A look at the Asacub mobile banking Trojan

The first version of Asacub, which we saw in June 2015, was a basic phishing app: it was able to send a list of the victim’s apps, browser history and contact list to a remote C2 server, send SMS messages to a specific phone number and turn off the screen on demand. This mobile Trojan has evolved since then, off the back of a large-scale distribution campaign by its creators in spring and summer 2017), helping it to claim top spot in last year’s ranking of mobile banking Trojans – out-performing other families such as Svpeng and Faketoken. The Trojan has claimed victims in a number of countries, but the latest version steals money from owners of Android devices connected to the mobile banking service of one of Russia’s largest banks.

The malware is spread via an SMS messages containing a link and an offer to view a photo or MMS message. The link directs the victim to a web page containing a similar sentence and a button for downloading the Trojan APK file to the device.

Asacub masquerades as an MMS app or a client of a popular free ads service.

Once installed, the Trojan starts to communicate with the C2 server. Data is transferred in JSON format and includes information about the victim’s device – smartphone model, operating system, mobile operator and Trojan version.

Asacub is able to withdraw funds from a bank card linked to the phone by sending an SMS for the transfer of funds to another account using the number of the card or mobile phone. Moreover, the Trojan intercepts SMS messages from the bank that contain one-time passwords and information about the balance of the linked bank card. Some versions of the Trojan can autonomously retrieve confirmation codes from such SMS messages and send them to the required number. What’s more, the victim can’t subsequently check the balance via mobile banking or change any settings, because after receiving a command with the code 40, the Trojan prevents the banking app from running on the phone.

You can read more here.

BusyGasper – the unfriendly spy

Early in 2018, our mobile intruder detection technology was triggered by a suspicious Android sample that turned out to belong to a new spyware family that we named BusyGasper. The malware isn’t sophisticated, but it does demonstrate some unusual features for this type of threat. BusyGasper is a unique spy implant with stand-out features such as device sensor listeners, including motion detectors that have been implemented with a degree of originality. It has an incredibly wide-ranging protocol – about 100 commands – and an ability to bypass the Doze battery saver. Like other modern Android spyware, it is capable of exfiltrating data from messaging applications – WhatsApp, Viber and Facebook. It also includes some keylogging tools – the malware processes every user tap, gathering its co-ordinates and calculating characters by matching given values with hardcoded ones.

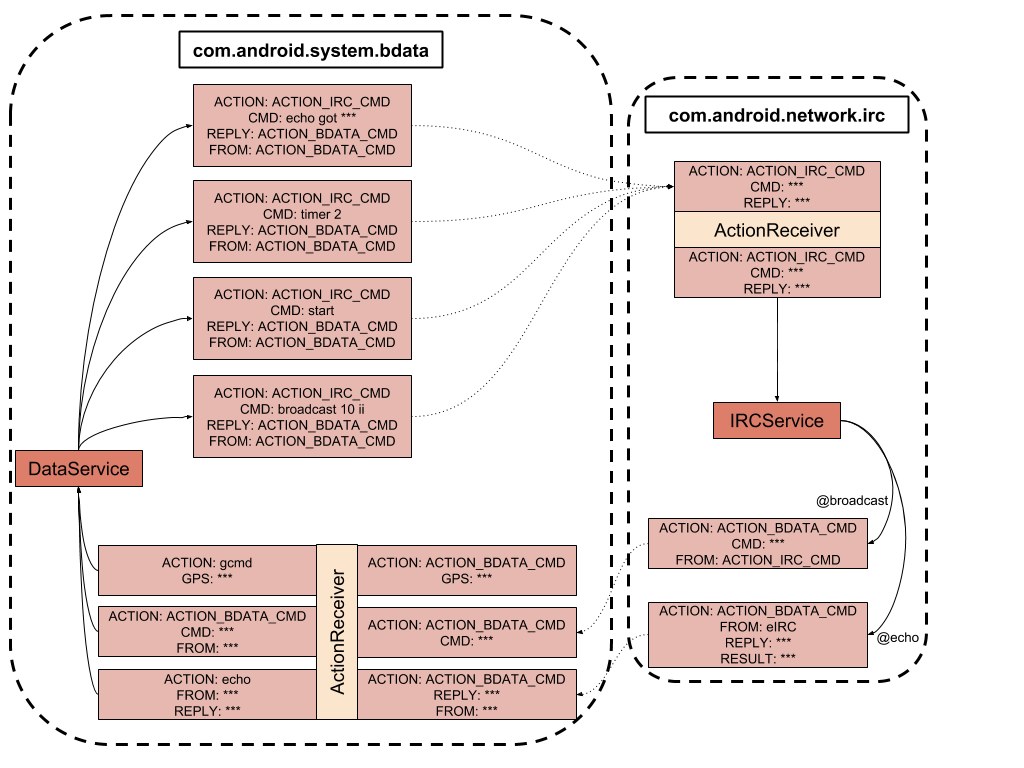

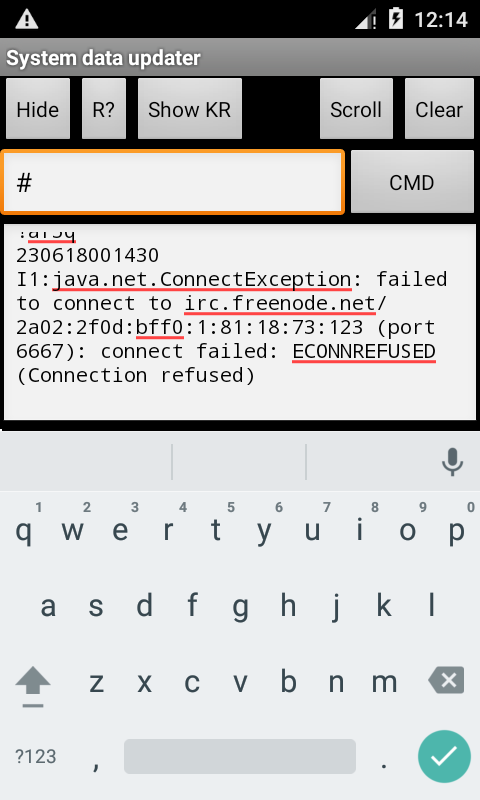

The malware has a multi-component structure and can download a payload or updates from its C2 server, which happens to be an FTP server belonging to the free Russian web hosting service Ucoz. It is noteworthy that BusyGasper supports the IRC protocol, which is rarely seen among Android malware. In addition, it can log in to the attacker’s email inbox, parse emails in a special folder for commands and save any payloads to a device from email attachments.

There is a hidden menu for controlling the different implants that seems to have been created for manual operator control. To activate the menu, the operator needs to call the hardcoded number 9909 from an infected device.

The operator can use this interface to type any command. It also shows a current malware log.

This particular operation has been active since May. We have found no evidence of spear phishing or other common infection method. Some clues, such as the existence of a hidden menu mentioned above, suggest a manual installation method – the attackers gaining physical access to a victim’s device in order to install the malware. This would explain the number of victims – less than 10 in total, all located in the Russia. There are no similarities to commercial spyware products or to other known spyware variants, which suggests that BusyGasper is self-developed and used by a single threat actor. At the same time, the lack of encryption, use of a public FTP server and the low OPSEC level could indicate that less skilled attackers are behind the malware.

Thinking outside the [sand]box

One of the security principles built into the Android operating system is that all apps must be isolated from one another. Each app, along with its private files, operate in ‘sandbox’ that can’t be accessed by other apps. The point is to ensure that, even if a malicious app infiltrates your device, it’s unable to access data held by legitimate apps – for example, the username and password for your online banking app, or your message history. Unsurprisingly, hackers try to find ways to circumvent this protection mechanism.

In August, at DEF CON 26, Checkpoint researcher, Slava Makkaveev, discussed a new way of escaping the Android sandbox, dubbed a ‘Man-in-the-Disk’ attack.

Android also has a shared external storage, named External Storage. Apps must ask the device owner for permission to access this storage area – the privileges required are not normally considered dangerous, and nearly every app asks for them, so there is nothing suspicious about the request per se. External storage is used for lots of useful things, such as to exchange files or transfer files between a smartphone and a computer. However, external storage is also often used for temporarily storing data downloaded from the internet. The data is first written to the shared part of the disk, and then transferred to an isolated area that only that particular app can access. For example, an app may temporarily use the area to store supplementary modules that it installs to expand its functionality, additional content such as dictionaries, or updates.

The problem is that any app with read/write access to the external storage can gain access to the files and modify them, adding something malicious. In a real-life scenario, you may install a seemingly harmless app, such as a game, that may nevertheless infect your smartphone with malware. Slava Makkaveev gave several examples in his DEF CON presentation.

Google researchers discovered that the same method of attack could be applied to the Android version of the popular game, Fortnite. To download the game, players need to install a helper app first, and it is supposed to download the game files. However, using the Man-in-the-Disk attack, someone can trick the helper into installing a malicious app. Fortnite developers – Epic Games – have already issued a new version of the installer. So, if you’re a Fortnite player, use version 2.1.0 or later to be sure that you’re safe. If you have Fortnite already installed, uninstall it and then reinstall it from scratch using the new version.

How safe are car sharing apps?

There has been a growth in car sharing services in recent years. Such services clearly provide flexibility for people wanting to get around major cities. However, it raises the question of security – how safe is the personal information of people using these services?

The obvious reason why cybercriminals might be interested in car sharing is because they want to ride in someone’s car at someone else’s expense. But this could be the least likely scenario – it’s a crime that requires a physical point of presence and there are ways to cross check if the person who makes the booking is the one who gets the ride. The selling of hijacked accounts might be a more viable reason – driven by demand from those who don’t have a driving license or who have been refused registration by the car sharing service’s security team. Offers of this nature already exist on the market. In addition, if someone manages to hijack someone else’s car sharing account, they can track all their trips and steal things that are left behind in the car. Finally, a car that is fraudulently rented in somebody else’s name can always be driven to some remote place and cannibalized for spare parts, or used for criminal activity.

We tested 13 apps to see if their developers have considered security.

First, we checked to see if the apps could be launched on an Android device with root privileges and to see how well the code is obfuscated. This is important because most Android apps can be decompiled, their code modified (for example, so that user credentials are sent to a C2 server), then re-assembled, signed with a new certificate and uploaded again to an app store. An attacker on a rooted device can infiltrate the app’s process and gain access to authentication data.

Second, we checked to see if it was possible to create a username and password when using a service. Many services use a person’s phone number as their username. This is quite easy for cybercriminals to obtain as people often forget to hide it on social media, while car sharing customers can be identified on social media by their hashtags and photos.

Third, we looked at how the apps work with certificates and if cybercriminals have any chance of launching successful Man-in-the-Middle attacks. We also checked how easy it is to overlay an app’s interface with a fake authorization window.

The results of our tests were not encouraging. It’s clear that app developers don’t fully understand the current threats to mobile platforms – this is true for both the design stage and when creating the infrastructure. A good first step would be to expand the functionality for notifying customers of suspicious activities – only one service currently sends notifications to customers about attempts to log in to their account from a different device. The majority of the apps we analysed are poorly designed from a security standpoint and need to be improved. Moreover, many of the programs are not only very similar to each other but are actually based on the same code.

You can read our report here, including advice for customers of car sharing services and recommendations for developers of car sharing apps.

IT threat evolution Q3 2018