September in figures

The following statistics were compiled in September using data collected from computers running Kaspersky Lab products:

- 213,602,142 network attacks were blocked;

- 80,774,804 web-borne infections were prevented;

- 263,437,090 malicious programs were detected and neutralized on user computers;

- 91,767,702 heuristic verdicts were registered.

The cybercriminals’ new bag of tricks

BIOS infections: the final frontier?

September saw events that could well have a major bearing on the future development of malware and antivirus technology, following the discovery by experts from several antivirus companies of a Trojan capable of infecting BIOS.

By launching from BIOS immediately after the computer is turned on, a malicious program can gain control of all the boot-up stages of the computer or operating system. Injection of malicious code at this level was previously unheard of. Back in 1998, the CIH virus was capable of reprogramming BIOS, but all it could do was corrupt BIOS making it impossible to start the computer; it couldn’t gain control of the system.

Clearly, this is something that would interest virus writers, although the process is fraught with complications. The primary challenge is a nonstandard BIOS format: the author of a malicious program must support each and every manufacturer’s BIOS and get a handle on the ROM firmware algorithms.

The rootkit detected in September is designed to infect BIOS manufactured by Award and appears to have originated in China. The Trojan’s code is clearly unfinished and contains debug information, but we have verified its functionality and it works.

The rootkit has two main functions, with the main operations found in the code that is executed from the MBR. The sole task of the code injected into BIOS is to make sure that the infected backup is in the MBR and to restore the infection if it is absent. Since the infected boot record and corresponding sectors are in the same ISA ROM module, if any discrepancies are found then the MBR can be re-infected directly from the BIOS. This greatly increases the likelihood that the computer will remain infected, even if the MBR is cleaned up.

Kaspersky Lab technologies can successfully detect infections by this rootkit . There remains the question of whether infected BIOS can be treated, but this will become clear if more malware with similar functionality appears. We currently take the view that Rootkit.Win32.Mybios.a is a proof of concept and not intended for mass distribution. An article by our expert Vyacheslav Rusakov analyzes this ‘Bioskit’ in more detail at

https://securelist.com/.

Attacks against individual users

Closure of the Hlux/Kelihos botnet

September saw a major breakthrough in the battle against botnets – the closure of the Hlux botnet. Cooperation between Kaspersky Lab, Microsoft and Kyrus Tech not only led to the takeover of the network of Hlux-infected machines, the first time this had ever been done with a P2P botnet, but also the closure of the entire cz.cc domain. Throughout 2011 this domain was a hotbed of various threats: rogue antivirus programs (including for MacOS), backdoors and spyware. It also hosted the command and control centers for dozens of botnets.

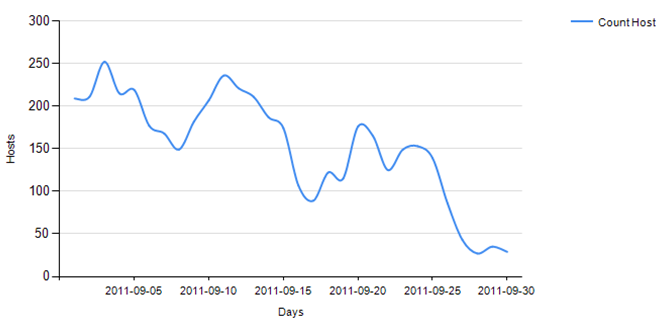

The fall in the number of malicious sites in the cz.cc domain (source: Kaspersky Security Network)

At the time it was taken offline the Hlux botnet numbered over 40,000 computers and was capable of sending out tens of millions of spam messages on a daily basis, performing DDoS attacks and downloading malware to victim machines. Kaspersky Lab tracked the botnet from early 2011 and following an analysis of all its components we cracked Hlux’s communication protocol and developed the corresponding tools to take control of its network. Microsoft has also taken legal action against a number of individuals it believes are linked to the creation of the botnet in a civil case.

Kaspersky Lab currently controls the botnet and we are in contact with the service providers of the affected users to help clean up infected systems. Detection for Hlux has been added to Microsoft’s Malicious Software Removal Tool, helping to significantly reduce the number of infected machines.

You can read more about the Hlux botnet and how it was closed it down in a blog by our expert Tillman Werner at

https://securelist.com.

The war on botnets continues unabated, and we currently have a number of dangerous zombie networks in our sights, so expect more news about similar closures in the future.

The DigiNotar hack

We have added the attack on Dutch certificate authority DigiNotar to the list of threats affecting individual users. Although it was the computers of commercial organizations that were compromised, one of the main aims of the hackers was the creation of fake SSL certificates for a number of popular resources, including social networks and email services that are used by individual users.

The hack occurred at the end of July and went unnoticed throughout August while the attacker manipulated the DigiNotar system to create several dozen certificates for resources such as Gmail, Facebook and Twitter. Their use was later recorded on the Internet as part of an attack on Iranian users. The fake certificates enable man-in-the-middle attacks to be conducted and, being installed at the provider level, allow all information between users and a server to be intercepted.

An anonymous hacker from Iran eventually admitted he was responsible for the attack and provided proof that he was involved. It was the same hacker who created several spoof certificates after a similar attack on a partner of Comodo, another certificate authority.

The DigiNotar story once again raises questions about how secure the existing system of hundreds of certificate authorities is, and merely discredits the very idea of digital certificates. There is little doubt that the security flaws exposed by these attacks are serious enough to require immediate attention and the creation of additional authorization tools that involve IT security companies, browser vendors as well as the certificate authorities, whose number most probably needs to be reduced.

Pushing rogue AV via Skype

Back in March Skype calls were being used to lure unsuspecting users to download rogue antivirus programs. If users’ Skype settings didn’t restrict calls from people not on their contact list, then they may well have received calls from specially created malicious accounts with names such as ONLINE REPORT NOTICE or System Service. If the calls were accepted, an automated voice informed users that their system was at risk and that they needed to visit a specific website. The site performed a fake system scan and, of course, “detected” security vulnerabilities or malware. In order to remove these threats the users were asked to purchase “antivirus software” which did nothing more than imitate antivirus activity.

This tactic was not particularly widespread earlier in the year, but more cases were registered in September, with users complaining about calls from an account named URGENT NOTICE. The calls stated that the security system on their computers was inactive. The users were told to visit a website where they were asked to pay $19.95 to activate security on their computers. The address of the offending website suggests that the same people that were behind the attacks in spring.

In order to block spam on Skype, you need to configure your settings so that you only receive calls, videos or messages from users on your contact list. If an account is being used as a service to call random users and your settings don’t block it, then you should inform the Skype administrators so it can be blocked.

Mobile threats

We detected 680 new variations of malicious programs for different mobile platforms in September – 559 of them were for Android. In recent months we have noticed a significant increase in the overall number of malicious programs for Android and, in particular, the number of backdoors: of the 559 malicious programs detected for Android, 182 (32.5%) were modifications with backdoor functionality (the corresponding figure for July was 46 and in August it had risen slightly to 54).

It was obvious that sooner or later the majority of malicious programs for mobile devices were going to make extensive use of the Internet for such things as connecting to remote servers to receive commands.

SpitMo + SpyEye = stolen mTANs

There are currently two known mobile Trojans – ZitMo and SpitMo – that are designed to intercept text messages containing mTANs sent by banks to their online customers. The former works in tandem with ZeuS, while the latter is linked to another notorious Trojan – SpyEye. ZitMo leads the way in terms of the number of platforms it can infect, although September saw SpitMo add a version capable of working on Android.

SpitMo and its partner in crime, SpyEye, operate in virtually the same way as the

ZitMo-Zeus duo. SpyEye’s configuration files suggest that it was targeting customers of several Spanish banks. Users of computers infected by SpyEye receive a message on a page that has been modified by the malware telling them to install an important smartphone application that supposedly protects text messages containing mTAN codes. In actual fact the malicious program SpitMo is installed, which sends all incoming SMS messages to a remote server that belongs to malicious users. The messages are sent in the following format:

SpitMo contains an XML configuration file which determines how the intercepted text message is sent: via HTTP or SMS. This type of functionality is new and we can no doubt expect to see further modifications being made to this kind of malware in the future.

Attacks via QR codes

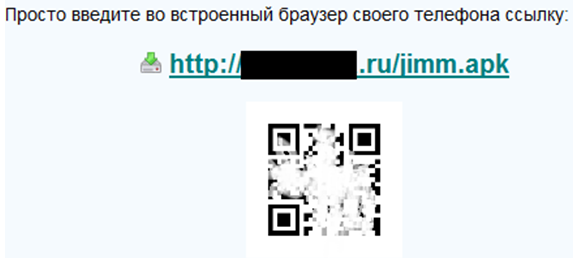

At the end of September we detected the first attempts at using QR codes in malicious attacks. Nowadays a lot of people use their PCs to find new apps for their mobile devices. When it comes to installing software on smartphones a variety of websites offer users a simplified process that involves scanning a QR code to start downloading an app without having to enter a URL manually.

Cybercriminals, it appears, have also decided to simplify downloads of malicious software. We detected several malicious websites containing QR codes for mobile apps (e.g. Jimm and Opera Mini) which included a Trojan capable of sending text messages to premium-rate short numbers.

By early October we had detected QR codes linked to malware for Android and J2ME – the cybercriminals’ favorite mobile platforms.

MacOS threats: the new Trojan concealed inside a PDF

In late September our F-Secure colleagues detected yet more malicious code aimed at Mac OS X users (detected by Kaspersky Lab as Backdoor.OSX.Imuler.a). This malicious program is capable of receiving additional commands from a control server as well as downloading random files and screenshots to the server from an infected system.

Unlike

Backdoor.OSX.Olyx.a, which was distributed in a RAR archive via email, in this case the cybercriminals have used a PDF document as a mask.

Receiving email attachments that have additional file extensions such as .pdf.exe or .doc.exe may well be normal for many Windows users, who simply delete them without opening them. However, the tactic proved to be a novelty for Mac users, especially given that there is no .exe. file extension in UNIX-like systems. As a result, Mac users who receive such files via email are more prone to launch malicious code masquerading as a PDF, an image or a doc etc.

Interestingly, in attacks of this type a password is not requested when the malicious code is launched — the code is installed in the directory of the current user and only functions with temporary folders.

This sort of technology has already been detected in the MacDefender malicious program. Fortunately, in the case of Imuler the scale of the problem was significantly smaller.

Attacks on state and corporate networks

It seems not a month goes by without an attack on a major company or state organization somewhere in the world. September was no exception.

Attack on Mitsubishi

News about an attack on the Japanese corporation Mitsubishi appeared in the middle of the month, although our research suggests that it was most probably launched as far back as in July and entered its active phase in August.

According to the Japanese press, approximately 80 computers and servers were infected at plants manufacturing equipment for submarines, rockets and the nuclear industry. Malicious programs, for example, were detected on computers at a shipbuilding yard in Kobe that specializes in the production of submarines and components for nuclear plants. Plants in Nagoya producing rockets and rocket engines were also targeted by attacks, as well as a plant in Nagasaki that builds patrol boats. Malware was also detected on computers at the company’s headquarters.

Kaspersky Lab experts managed to obtain samples of the malware used in the attack. It is safe to say that the attack was carefully planned and executed. It followed a familiar scenario: in late July a number of Mitsubishi employees received emails from cybercriminals containing a PDF file, which was an exploit for a vulnerability in Adobe Reader. The malicious component was installed as soon as the file was opened, resulting in the hackers getting full remote access to the affected system. From the infected computer the hackers then penetrated the company’s network still further, cracking servers and gathering information that was then forwarded to the hackers’ server. A dozen or so different malicious programs were used in the attack, some specifically developed with the company’s internal network structure in mind.

There is now no way of knowing exactly what information was stolen by the hackers, but it is likely that the affected computers contained confidential information of strategic importance.

Lurid

A potentially far more serious incident was uncovered by Trend Micro during research by the company’s experts. They managed to intercept requests to several servers that were being used to control a network of 1,500 compromised computers located mainly in Russia, former Soviet republics and countries in eastern Europe. This particular incident has been named Lurid.

Thanks to our colleagues at Trend Micro we managed to analyze the list of Russian victims. Analysis showed that we are dealing with a targeted attack against very specific organizations. The attackers were interested in the aerospace industry, scientific research institutes, several commercial organizations, state bodies and a number of media outlets.

Lurid simultaneously affected users in several countries and was launched at least as long ago as March of this year. As was the case with the Mitsubishi attack, emails were used at the initial stages. The actual volume and content of the data stolen are also difficult to pinpoint in the case of Lurid, though the list of targets speaks for itself.

Lessons from history: 10th anniversary of the Nimda worm

One of the more significant stories of the early 21st century was that of the Nimda worm. Ten years ago Nimda used a variety of methods to infect PCs and servers, but the most prominent infections, which amounted to a global epidemic, were spread via email attachments. On 18 September 2001, cybercriminals sent messages with attachments that contained a malicious executable file. This was a novelty at the time and unsuspecting users launched the application contained in the email. These days, nearly every user is aware of the risks of not only launching a program from a spam message but also of clicking links contained in messages from unknown senders.

The tactics may have changed in the past 10 years, but email still remains one of the most popular methods of spreading malware. Malicious users are a lot more cunning than they were 10 years ago, making use of vulnerabilities in popular document software. Users usually associate files with extensions such as .doc, .pdf, and .xls with documents containing texts and tables, and they do not normally arouse suspicion.

Vulnerabilities in programs are constantly being fixed, but many users fail to update the software installed on their computers and cybercriminals actively exploit this. The majority of users are wary of messages from strangers. That’s why, once a computer is infected, cybercriminals will steal the victim’s account details for email services, social networking sites, instant messengers etc. and send messages in the victim’s name to the people on his/her contact lists.

Attacks via email are particularly popular when a targeted attack is being carried out on an organization.

September ratings

Top 10 threats on the Internet

| 1 | Blocked | 89,37% |

| 2 | UFO:Blocked | 3,45% |

| 3 | Trojan.Script.Iframer | 2,27% |

| 4 | Trojan.Script.Generic | 1,79% |

| 5 | AdWare.Win32.Eorezo.heur | 1,47% |

| 6 | Exploit.Script.Generic | 1,02% |

| 7 | Trojan.Win32.Generic | 0,90% |

| 8 | Trojan-Downloader.Script.Generic | 0,74% |

| 9 | WebToolbar.Win32.MyWebSearch.gen | 0,65% |

| 10 | AdWare.Win32.Shopper.ee | 0,45% |

Top 10 sources of malware

| 1 | United States | 22,14% |

| 2 | Russian Federation | 15,18% |

| 3 | Germany | 14,37% |

| 4 | Netherlands | 7,27% |

| 5 | United Kingdom | 4,92% |

| 6 | Ukraine | 4,56% |

| 7 | China | 2,84% |

| 8 | Virgin Islands, British | 2,51% |

| 9 | France | 2,28% |

| 10 | Romania | 1,97% |

Top 10 malware hosts

| 1 | ru-download.in | 13.94% |

| 2 | jimmok.ru | 10.54% |

| 3 | ak.imgfarm.com | 10.15% |

| 4 | 72.51.44.90 | 9.05% |

| 5 | lxtraffic.com | 7.77% |

| 6 | literedirect.com | 5.90% |

| 7 | adult-se.com | 5.87% |

| 8 | jimmmedia.com | 4.70% |

| 9 | best2banners.com | 3.76% |

| 10 | h1.ripway.com | 3.75% |

Top 10 malicious domain zones

| 1 | com | 36982032 |

| 2 | ru | 19796243 |

| 3 | net | 2999267 |

| 4 | info | 2898749 |

| 5 | in | 2712188 |

| 6 | org | 1885626 |

| 7 | cc | 1103876 |

| 8 | tv | 1046426 |

| 9 | kz | 954370 |

| 10 | tk | 585603 |

Top 10 countries with the highest percentage of attacks against users’ computers (Web Antivirus)

| 1 | Russian Federation | 41,103 |

| 2 | Armenia | 40,1141 |

| 3 | Kazakhstan | 34,5965 |

| 4 | Belarus | 33,9831 |

| 5 | Oman | 31,752 |

| 6 | Azerbaijan | 31,1518 |

| 7 | Ukraine | 30,8786 |

| 8 | Korea, Republic of | 30,7139 |

| 9 | Iraq | 29,1809 |

| 10 | Sudan | 29,094 |

Monthly Malware Statistics: September 2011