Introduction

Online banking is now a run-of-the-mill affair for most. More and more banks are trying to maximize the range of services available to clients online. With the added convenience and speed, it might seem as though there is no downside to online banking. However, where there is money — in any form — there are usually scammers.

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when the first attacks against online banking customers were launched — and in this case, it’s not all that important. We have encountered two types of attacks: attacks that use classic phishing methods, and attacks that employ a variety of malicious programs. Initially, these attacks were meant to identify online banking system users — i.e. to harvest usernames and passwords. As banks improved their security mechanisms, cyber criminals responded by improving malicious programs and learned how to bypass most of the transaction confirmation processes used in online banking systems.

These days, the most popular security features of online banking services are TAN codes (Transaction Authentication Number) with digital signatures. In some cases, banks send TAN codes via a text message (these are called mTANs, or mobile transaction authentication numbers). Prior to September 2010, there were no recorded instances of attacks using mTAN codes. In 2009, rumors went around that hackers were buying up Nokia 1100s in bulk for tens of thousands of dollars — not just any 1100s, but specifically ones that were manufactured at a factory in Bochum, Germany. Allegedly, these particular handsets had special features (or vulnerabilities?) that made it possible to intercept all text messages, including those containing mTAN codes. However, no such cases were ever confirmed.

When the ZeuS Trojan for mobile platforms (aka ZeuS-in-the-Mobile, or ZitMo) came out in late September 2010, it became the first malicious program designed to steal mTAN codes. This article will discuss ZitMo in detail.

ZitMo’s plan of attack

Mobile ZeuS, or Trojan-Spy.*.Zitmo, was designed for one sole purpose: to quickly steal mTAN codes without mobile users noticing. The first important thing to point out is that ZitMo works in close collaboration with the regular ZeuS Trojan. By the regular ZeuS we will mean a modification of the Trojan that targets the Win32 platform and which is classified as Trojan-Spy.Win32.Zbot by Kaspersky Lab.

Readers may recall that ZeuS for PCs running on Windows has been around for some time now. Its first modifications appeared back in 2007. Check out Dmitri Tarakanov’s article for more about ZeuS.

What happens when a user whose computer is infected with ZeuS gets ready to log in to an online banking system? The user attempts to navigate to his bank’s webpage and log into the system. The PC version of ZeuS registers that the victim is going to an address of interest, and modifies this webpage in the browser so that the personal data entered by the user for authentication is not sent to the bank, but to the ZeuS botnet command center.

How ZeuS works

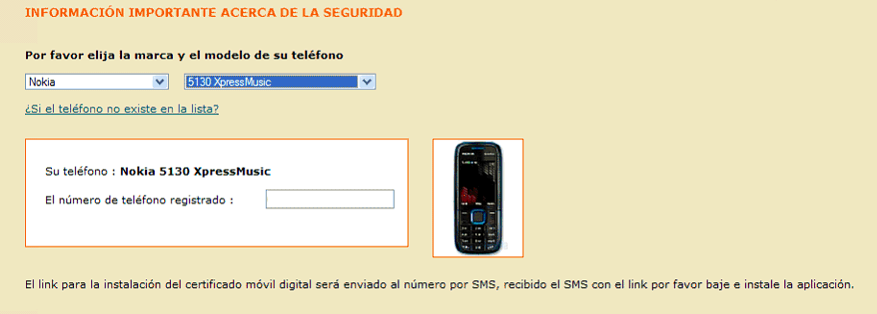

Sometime in September 2010, malicious users added a new function to the PC-based ZeuS. The way it worked remained more or less the same, only now a modified authentication page would also ask the user to enter data about their mobile device (the make, model, and telephone number) in addition to their username and password. Users were told that the data was requested for the alleged purpose of certificate updates.

A portion of an online banking authentication page which has been modified by malicious users. This

page asks users to enter information about their telephone model and number.

(Source: http://securityblog.s21sec.com/2010/09/zeus-mitmo-man-in-mobile-ii.html)

Sooner or later, users who provided information to malicious users about their cell phones would receive a text messages asking them to install a new security certificate. This “security certificate” could be downloaded via a link that was provided in the text message. However, this “certificate” was in fact the mobile version of the ZeuS Trojan. If the user followed the link, downloaded and installed the application, then his mobile phone would be infected by ZitMo, the primary function of which is to send a text message to a malicious user’s phone as specified in the body of the Trojan.

ZitMo is still spread in the same way: users download it to their mobile devices under the assumption that it is legitimate software.

The malicious users who successfully used the PC-based ZeuS to steal personal user data for online banking systems and infect victims’ phones with ZitMo were thus able to overcome the last barrier of online banking security systems: the mTAN code. By entering a user’s login and password, they were able to access their bank accounts and conduct transactions (such as transferring money from the user’s account to their own bank accounts). These transactions required additional authentication using a code sent by the bank via text message to the client’s phone. After the client submitted a transaction request, the bank would send the client an authentication code. The code would be sent to the ZitMo-infected handset, which immediately forwarded it to the malicious user’s number, who would then use the stolen mTAN to authenticate the transaction. And the victim would be none the wiser.

The attacks are generally orchestrated as follows:

- Cyber criminals use the PC-based ZeuS to steal the data needed to access online banking accounts and client cell phone numbers.

- The victim’s mobile phone (see point 1) receives a text message with a request to install an updated security certificate, or some other necessary software. However, the link in the text message will actually lead to the mobile version of ZeuS.

- If the victim installs this software and infects the phone, the malicious user can then use the stolen personal data and attempt to make cash transactions from the compromised account, but still needs an mTAN code to authenticate the transaction.

- The bank sends out a text message with the mTAN code to the client’s mobile phone.

- ZitMo forwards the text message with the mTAN code to the malicious user’s phone.

- The malicious user is then able to use the mTAN code to authenticate the transaction.

Known attacks

ZitMo’s was first detected on September 25, 2010. At that time, the Spanish-based data security company S21sec had written about this threat (see: http://securityblog.s21sec.com/2010/09/zeus-mitmo-man-in-mobile-i.html). However, it was not clear which banks were targeted. All of the data available leads us to believe that the victims were clients of one Spanish bank.

After that article was published, antivirus companies began their own research. S21sec reported it had detected ZitMo on two different mobile platforms: Symbian and BlackBerry. Examples of the malicious program for Symbian were quickly found, but for a long time the mobile version of ZeuS for BlackBerry existed only in theory and on paper as no one was able to get their hands on a sample.

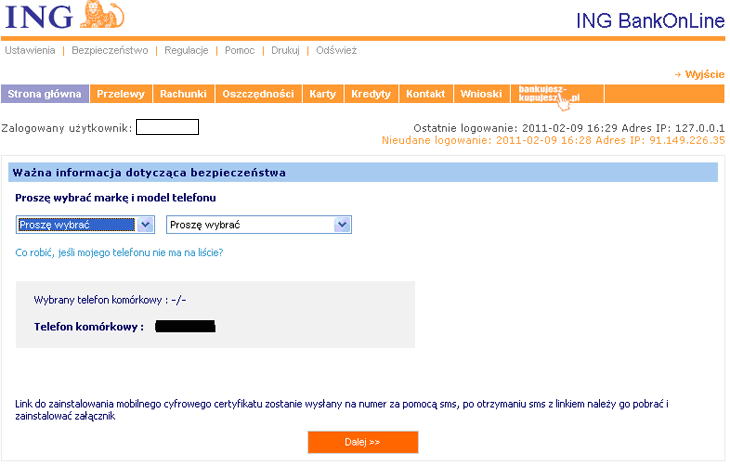

A Polish blogger wrote about the second ZitMo attack on 21 February 2011 (see: http://niebezpiecznik.pl/post/zeus-straszy-polskie-banki/) and the names of the banks whose clients were being targeted finally came to light: ING and mBank.

ZeuS’s modification of ING’s online banking web page

(Source: http://niebezpiecznik.pl/post/zeus-straszy-polskie-banki/)

The list of targeted platforms also grew, and now included smartphones running on Windows Mobile.

At that point, only the ZitMo attacks described above had been detected. It remains unclear whether other attacks had taken place. If so, then they will probably not be discussed in public.

Platforms

At the time of this article’s publication (October 2011), various modifications of ZitMo had been detected for the following platforms: Symbian, Windows Mobile, BlackBerry and Android.

Above, we described the general sequence of events that occur during attacks and the main objective of the mobile version of ZeuS, i.e. to obtain text messages with mTAN codes. The functions for ZitMo versions targeting different platforms (save for Android) are identical, although it’s still important to take a closer look at the individual versions for each mobile platform.

For starters, let us take a look at one crucial and interesting detail of all ZitMo versions, with the exception of Android. A Trojan running on a smartphone is controlled by commands that are received via text message. So essentially, ZitMo is a text-bot, the C&C of which is another telephone, or to be more precise, a telephone number.

By July 2011, the following C&C numbers had been identified:

- +44778148****

- +44778148****

- +44778148****

- +44778620****

- +44778148****

These are all UK numbers. Is this indirect evidence that the authors of the malicious program were located in the UK during the attack? It’s possible.

Symbian

The ZitMo version for Symbian was the first sample of this threat obtained by antivirus companies (in late September 2010). Another point worth mentioning is that this malicious program was given a legitimate digital signature (which has since been recalled).

One of ZitMo’s digital signatures

So how does ZitMo for Symbian operate?

Immediately after a smartphone is infected, the Trojan sends the text message ‘App installed OK’ to the C&C number, thus notifying the malicious users that the program has been installed and is ready to accept commands. ZitMo then creates a database named NumbersDB.db with three tables: tbl_contact, tbl_phone, and tbl_history.

After infection, ZitMo can receive text messages from the C&C number with the following commands:

- ADD SENDER

- REM SENDER

- SET SENDER

- SET ADMIN

- BLOCK ON or OFF

- ON or OFF

The ADD SENDER command is one of the most critical for ZitMo, since it orders the forwarding of text messages from specified telephone numbers (the numbers which banks use to send mTAN codes via text message) to the C&C number. In other words, this command activates the forwarding of text messages with authentication codes for transactions executed by malicious users.

The REM SENDER command ends the forwarding of text messages from the number specified in the command to the C&C number.

The SET SENDER command allows the malicious users to update the telephone number from which the text messages are forwarded to the C&C.

The SET ADMIN command lets malicious users change the C&C number. This is the only command that can be sent to an infected mobile device from a telephone number other than the C&C number, enabling malicious users to change the command center.

The BLOCK ON/BLOCK OFF commands allow malicious users to block or unblock all incoming and outgoing calls.

The ON/OFF command allows the malicious users to switch ZitMo on and off.

ZitMo does not contain any “personal” commands and is designed with one goal in mind: to transfer text messages with mTAN codes.

The second version of ZitMo, detected in a second identified attack, was slightly different from the first, but only negligibly. First of all, what is clear is that the C&C number was different. However, the country code (UK) in this number remained the same. Second, ZitMo began to scan both incoming and outgoing text messages, which is a bit strange, since the primary objective of the Trojan is to harvest mTAN codes. The third difference is that ‘App installed OK’ text messages were sent every time a SET ADMIN command was successfully received and executed. Previously these messages were only sent after a Trojan was installed.

Windows Mobile

ZitMo for Windows Mobile was detected during the Trojan’s second known attack, which also involved the Symbian version. It comes as no surprise that the C&C number for both the Windows Mobile and Symbian versions of the threat was the same.

A fragment of code from Trojan-Spy.WinCE.Zitmo.a

A fragment of code from Trojan-Spy.SymbOS.Zitmo.b

There are no differences in the functions between the Windows Mobile and Symbian versions of ZitMo. The Trojan is capable of receiving and executing the same commands on both platforms.

BlackBerry

The BlackBerry version of ZitMo turned out to be quite complex and a bit of a mystery. The threat was first identified in the same blog which announced the first confirmed appearance of ZitMo. But after five months of research, antivirus companies could not detect any files associated with ZitMo for BlackBerry and some people began to speculate that there was, in fact, no active BlackBerry version of ZitMo. Kaspersky Lab finally detected the file sertificate.cod shortly after the second ZitMo attack in late February 2011, which turned out to be the elusive ZueS-in-the-Mobile for BlackBerry.

A fragment of the sertificate.cod file

A quick glance at the file shows that in terms of the commands for this ZitMo version, there are no major differences from the other versions. A more detailed analysis brought the following to light.

The main methods used by this Trojan are stored in the file OptionDB.java. Among the names of the methods, one can find getAdminNumber, which is used, among other things, in the following Trojan installation confirmation process:

A part of the Trojan’s installation confirmation process

Logical methods can be found, such as isForwardSms, which determines whether or not a text message will be forwarded, and isBlockAllCalls determines whether or not telephone calls will be blocked.

The main processes required by this program’s operations can be found in the file SmsListener.java. These include, for example, a number verification process to identify the senders of incoming text messages that then determines which messages should be forwarded to the malicious users.

Android

ZitMo for Android was detected last of all, in early July 2011. The sample that was found is very different from all previous ZeuS-in-the-Mobile versions. The threat’s functions are so primitive that it might seem as though the APK file is entirely unconnected to ZitMol. However, research confirmed that it really is ZeuS-in-the-Mobile for Android.

We have written about how ZeuS operates. In brief, when a user attempts to visit his bank’s website and log in, he will instead see a page that has been modified by ZeuS asking him to enter data which is then sent to a malicious user’s server, not the bank.

The first attacks using ZitMo for Android began in the first two weeks of June. The tactics used to spread the threat were the same. The following message was found in one of the configuration files of Trojan-Spy.Win32.Zbot:

Once a user selects “Android” and clicks “Continue”, he is led to the following page, where he is “strongly recommended” to download “a special software which will help to protect you from fraud”.

A recommendation to download a so-called anti-fraud utility

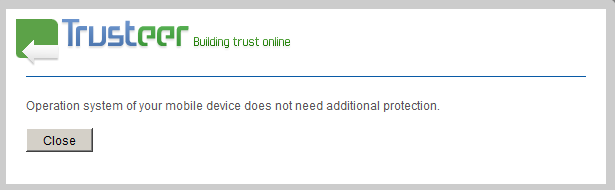

If a user selects an OS other than Android, then nothing will happen. The user will see the following message.

The message for non-Android users stating that no “additional protection” is required

In other words, this specific version of ZitMo targets the Android platform exclusively.

After downloading and installing the allegedly legitimate software, the user will receive the malicious program on his smartphone, the only purpose of which is to forward all incoming text messages (including those with mTAN codes) to a remote server (http://******rifty.com/security.jsp) in the following format:

There are no other additional functions — not even any C&C numbers or text message commands in ZitMo for Android! However, ZitMo for Android still definitely has a connection to the PC-based ZeuS.

Also of note: the malicious program has been on the Android Market for some time now. It was uploaded there on 18 June, although the date it was removed is not clear. It was downloaded from Android Market less than 50 times.

What next?

The ZitMo Trojan, which works in collaboration with the PC-based ZeuS Trojan, is perhaps one of the most complex recent mobile threats for the following reasons:

- It is a Trojan with a very narrow specialization: forwarding incoming text messages with mTAN codes to malicious users (or a server, in cases involving ZitMo for Android) so that the latter can execute financial transactions using hacked bank accounts.

- There are versions for multiple mobile platforms. ZitMo versions for Symbian, Windows Mobile, BlackBerry, and Android have been detected.

- It works with ZeuS as a “team”. If you look at ZitMo separately, i.e. without any connection to the PC-based ZeuS, then it becomes mere spyware capable of forwarding text messages. However, if used in combination with the classic PC-based ZeuS, then malicious users will be able to clear the final hurdle of online banking authentication processes using stolen mTAN codes.

In the future, attacks involving ZitMo (or a malicious program with similar functions) that are designed to somehow steal mTAN codes (or perhaps other confidential information that is sent via text message) will continue, although it is likely that they will become more specifically targeted against a smaller number of victims.

ZeuS-in-the-Mobile – Facts and Theories

Captan

Who is to determine how we can position behind?