Once again, it’s time for us to deliver our customary retrospective of the key events that have defined the threat landscape in 2013. Let’s start by looking back at the things we thought would shape the year ahead, based on the trends we observed in the previous year.

- Targeted attacks and cyber-espionage

- The onward march of ‘hacktivism’

- Nation-state-sponsored cyber-attacks

- The use of legal surveillance tools

- Cloudy with a chance of malware

- Vulnerabilities and exploits

- Cyber extortion

- Who do you trust?

- Mac OS malware

- Mobile malware

- Dude, where’s my privacy?!

If we now focus on the highlights on 2013, you can judge for yourself how well we did in predicting the future.

The top stories of 2013

Here’s our shortlist of the top security stories of 2013.

1. New “old” cyber-espionage campaigns

In any retrospective of top stories of 2013 you might expect to read about incidents that occurred this year. But it’s not quite that straightforward when looking at targeted attacks. Often, the roots of the attack reach back in time from the point at which they become known and are analyzed and reported. You might remember, for example, that this was the case with Stuxnet – the more we analyzed it, the further back we had to place its date of origin. It’s true also of some of the major cyber-espionage campaigns we’ve seen this year.

Red October is a cyber-espionage campaign that has affected hundreds of victims around the world – including diplomatic and government agencies, research institutions, energy and nuclear groups and trade and aerospace organizations. The malware is highly sophisticated – among other things, it includes a ‘resurrection mode’ that enables the malware to re-infect computers. The code is highly modular, allowing the attackers to tweak the code easily for each specific target. Interestingly, Red October didn’t just harvest information from traditional endpoints, but also from mobile devices connected to the victims’ networks – a clear recognition by cybercriminals that mobile devices are a core component of today’s business environment and contain valuable information. We published the results of our analysis in January 2013, but it’s clear that the campaign dates back to 2008.

In February, we published our analysis of MiniDuke, designed to steal data from government agencies and research institutions. Our analysis uncovered 59 high profile victim organizations in 23 countries, including Ukraine, Belgium, Portugal, Romania, the Czech Republic, Ireland, Hungary and the US. Like many targeted attacks, MiniDuke combined the use of ‘old school’ social engineering tactics with sophisticated techniques. For example, MiniDuke included the first exploit capable of bypassing the Adobe Acrobat Reader sandbox. In addition, compromised endpoints received instructions from the command-and-control server via pre-defined Twitter accounts (and used Google search as a fallback method).

We learned of a wave of attacks in March that targeted top politicians and human rights activists in CIS countries and Eastern Europe. The attackers used the TeamViewer remote administration tool to control the computers of their victims, so the operation became known as ‘TeamSpy’. The purpose of the attacks was to gather information from compromised computers. Though not as sophisticated as Red October, NetTraveler and other campaigns, this campaign was nevertheless successful – indicating that not all successful targeted attacks need to build code from scratch.

NetTraveler (also known as “NetFile”), which we announced in June, is another threat that, at the time of discovery, had long been active – in this case, since 2004.

This campaign was designed to steal data relating to space exploration, nano-technology, energy production, nuclear power, lasers, medicine and telecommunications. NetTraveler was successfully used to compromise more than 350 organizations across 40 countries – including Mongolia, Russia, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, China, Tajikistan, South Korea, Spain and Germany. The targets were from state and private sector organizations that included government agencies, embassies, oil and gas companies, research centers, military contractors and activists.

If your organization has never suffered an attack, it’s easy to tell yourself that ‘it won’t happen to me’, or to imagine that most of what we hear about malware is just hype. It’s easy to read the headlines and draw the conclusion that targeted attacks are a problem only for large organizations. But not all attacks involve high profile targets, or those involved in ‘critical infrastructure’ projects. In truth, any organization can become a victim. Every organization holds data that could be of value to cybercriminals, or they can be used as a ‘stepping-stones’ to reach other companies. This point was amply illustrated by the Winnti and Icefog attacks.

In April we published a report on the cybercrime group ‘Winnti’. This group, active since 2009, focuses on stealing digital certificates signed by legitimate software vendors, as well as intellectual property theft (including theft of source code for online game projects). The Trojan used by the group is a DLL library compiled for 64-bit Windows environments. It uses a properly signed driver and operates as a fully-functional Remote Administration Tool – giving the attackers full control over the compromised computer. In total, we found that more than 30 companies in the online gaming industry fell victim to the group’s activities – mostly in South-East Asia, but also affecting companies in Germany, the US, Japan, China, Russia, Brazil, Peru, Belarus and the UK. This group is still active.

The Icefog attacks that we announced in September (discussed in the next section of this report) were focused on the supply chain and, as well assensitive data from within the target networks, also gathered e-mail and network credentials to resources outside the target networks.

2. Cyber-mercenaries: a new emerging trend

On the face of it, Icefog seems to be a targeted attack like any other. It’s a cyber-espionage campaign, active since 2011, focused mainly in South Korea, Taiwan and Japan, but also in the US, Europe and China. Similarly, the attackers use spear-phishing e-mails – containing either attachments or links to malicious web sites – to distribute the malware to their victims. As with any such attack, it’s difficult to say for sure how many victims there have been, but we have seen several dozen victims running Windows and more than 350 running Mac OSX (most of the latter are in China).

However, there are some key distinctions from other attacks that we’ve discussed already. First, Icefog is part of an emerging trend that we’re seeing – attacks by small groups of cyber-mercenaries who conduct small hit-and-run attacks. Second, the attackers specifically targeted the supply chain – their would-be victims include government institutions, military contractors, maritime and ship-building groups, telecommunications operators, satellite operators, industrial and high technology companies and mass media. Third, their campaigns rely on custom-made cyber-espionage tools for Windows and Mac OSX and they directly control the compromised computers; and in addition to Icefog, we have noticed that they use backdoors and other malicious tools for lateral movement within the target organizations and for exfiltration of data.

The Chinese group ‘Hidden Lynx’, whose activities were reported by researchers at Symantec in September , fall into the same category – ‘guns-for-hire’ performing attacks to order using cutting-edge custom tools. This group was responsible for, among others, an attack on Bit9 earlier this year.

Going forward, we predict that more of these groups will appear as an underground black market for “APT” services begins to emerge.

3. Hacktivism and leaks

Stealing money – either by directly accessing bank accounts or by stealing confidential data – is not the only motive behind security breaches. They can also be launched as a form of political or social protest, or to undermine the reputation of the company being targeted. The fact is that the Internet pervades nearly every aspect of life today. For those with the relevant skills, it can be easier to launch an attack on a government or commercial web site than it is to co-ordinate a real-world protest or demonstration.

One of the weapons of choice for those who have an ax to grind is the DDoS (Distributed Denial of Service) attack. One of the biggest such attacks in history (some would say *the* biggest) was directed at Spamhaus in March. It’s estimated that, at its peak, the attack reached a throughput of 300gbps. One organization suspected of launching it was called Cyberbunker. The conflict between this organization and Spamhaus dates back to 2011, but reached a peak when Cyberbunker was denylisted by Spamhaus a few weeks before the incident. The owner of Cyberbunker denied responsibility, but claimed to be a spokesperson for those behind it. The attack was certainly launched by someone capable of generating huge amounts of traffic. To mitigate this, Spamhaus was forced to move to CloudFlare, a hosting and service provider known for dissipating large DDoS attacks. While some of the ‘it’s the end of the world as we know it’ headlines might have overstated the effects of this event, the incident highlights the impact that a determined attacker can have.

While the attack on Spamhaus appears to have been an isolated incident, ongoing hacktivist activities by groups who have been active for some time have continued this year. This includes the ‘Anonymous’ group. This year it has claimed responsibility for attacks on the US Department of Justice, MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and the web sites of various governments – including Poland, Greece, Singapore, Indonesia and Australia (the last two incidents involved an exchange between Anonymous groups in their respective countries). The group also claims to have hacked the wi-fi network of the British parliament during protests in Parliament Square during the first week of November.

Those claiming to be part of the ‘Syrian Electronic Army’ (supporters of Syria’s president, Bashar-al-Assad) have also been active throughout the year. In April, they claimed responsibility for hacking the Twitter account of Associated Press and sending a false tweet reporting explosions at the White House – which wiped $136 billion off the DOW. In July the group compromised the Gmail accounts of three White House employees and the Twitter account of Thomson Reuters.

It’s clear that our dependence on technology, together with the huge processing power built into today’s computers, means that we’re potentially vulnerable to attack by groups of people with diverse motives. So it’s unlikely that we’ll see an end to the activities of hacktivists or anyone else choosing to launch attacks on organizations of all kinds.

4. Ransomware

The methods used by cybercriminals to make money from their victims are not always subtle. ‘Ransomware’ programs operate like a computer-specific ‘denial-of-service’ attack – they block access to a computer’s file system, or they encrypt data files stored on the computer. The modus operandi can vary. In areas where levels of software piracy are high, for example, ransomware Trojans may claim to have identified unlicensed software on the victim’s computer and demand payment to regain access to the computer. Elsewhere, they purport to be pop-up messages from police agencies claiming to have found child pornography or other illegal content on the computer and demanding a fine. In other cases, there’s no subterfuge at all – they simply encrypt the data and warn you that you must pay in order to recover your data. This was the case with the Cryptolocker Trojan that we analyzed in October.

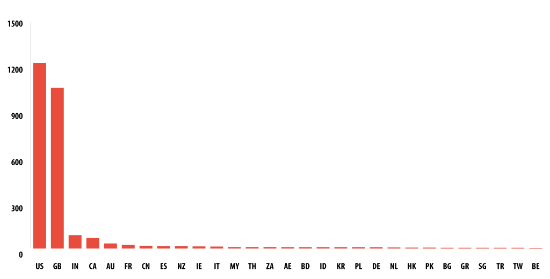

Cryptolocker downloads an RSA public key from its command-and-control (C2) server. A unique key is created for each new victim and only the authors have access to the decryption keys. To connect to the C2 server, Cryptolocker uses a domain generation algorithm that products 1,000 unique candidate domain names every day. The cybercriminals give their victims only three days to pay up – and they reinforce their message with scary wallpaper that warns them that if they don’t pay up in time their data will be gone forever. They accept different forms of payment, including Bitcoin. The most affected countries are the UK and US, distantly followed by India, Canada and Australia.

In this case there’s little difficulty in removing the malicious application, or even rebuilding the infected computer. But the data may potentially be lost forever. Sometimes in the past, we’ve been able decrypt the hijacked data. But that isn’t always possible if the encryption is very strong, as with some of the Gpcode variants. It is also true of Cryptolocker. That’s why it’s essential that individuals and businesses always make regular backups. If data is lost – for any reason – an inconvenience doesn’t turn into a disaster.

Cryptolocker wasn’t the only extortion program that made the headlines this year. In June we saw an Android app called ‘Free Calls Update’ – a fake anti-malware program designed to scare its victims into paying money to remove non-existent malware from the device. Once installed, the app tries to gain administrator rights: this allows it to turn wi-fi and 3G on and off; and prevents the victim from simply removing the app. The installation file is deleted afterwards, in a ploy to evade detection by any legitimate anti-malware program that may be installed. The app pretends to identify malware and prompts the victim to buy a license for the full version to remove the malware. While the app is browsing, it displays a warning that malware is trying to steal pornographic content from the phone.

5. Mobile malware and app store (in)security

The explosive growth in mobile malware that began in 2011 has continued this year. There are now more than 148,427 mobile malware modifications in 777 families. The vast majority of it, as in recent years, is focused on Android – 98.05% of mobile malware found this year targets this platform. This is no surprise. This platform ticks all the boxes for cybercriminals: it’s widely-used, it’s easy to develop for and people using Android devices are able to download programs (including malware) from wherever they choose. This last factor is important: cybercriminals are able to exploit the fact that people download apps from Google Play, from other marketplaces, or from other web sites. It’s also what makes it possible for cybercriminals to create their own fake web sites that masquerade as legitimate stores. For this reason, there is unlikely to be any slowdown in development of malicious apps for Android.

The malware targeting mobile devices mirrors the malware commonly found on infected desktops and laptops – backdoors, Trojans and Trojan-Spies. The one exception is SMS-Trojan programs – a category exclusive to smartphones.

The threat isn’t just growing in volume. We’re seeing increased complexity too. In June we analyzed the most sophisticated mobile malware Trojan we’ve seen to-date, a Trojan named Obad. This threat is multi-functional: it sends messages to premium rate numbers, downloads and installs other malware, uses Bluetooth to send itself to other devices and remotely performs commands at the console. This Trojan is also very complex. The code is heavily obfuscated and it exploits three previously unpublished vulnerabilities. Not least among these is one that enables the Trojan to gain extended Device Administrator privileges – but without it being listed on the device as one of the programs that has these rights. This makes it impossible for the victim to simply remove the malware from the device. It also allows the Trojan to block the screen. It does this for no more than 10 seconds, but that’s enough for the Trojan to send itself (and other malware) to nearby devices – a trick designed to prevent the victim from seeing the Trojan’s activities.

Obad also uses multiple methods to spread. We’ve already mentioned the use of Bluetooth. In addition, it spreads through a fake Google Play store, by means of spam text messages and through redirection from cracked sites. On top of this, it’s also dropped by another mobile Trojan – Opfake.

The cybercriminals behind Obad are able to control the Trojan using pre-defined strings in text messages. The Trojan can perform several actions. including sending text messages, pinging a specified resource, operating as a proxy server, connecting to a specified address, downloading and installing a specified file, sending a list of apps installed on the device, sending information on a specific app, sending the victim’s contacts to the server and performing commands specified by the server.

The Trojan harvests data from the device and sends it to the command-and-control server – including the MAC address of the device, the operating name, the IMEI number, the account balance, local time and whether or not the Trojan has been able to successfully obtain Device Administrator rights. All of this data is uploaded to the Obad control-and-command server: the Trojan first tries to use the active Internet connection and, if no connection is available, searches for a nearby Wi-Fi connection that doesn’t require authentication.

6. Watering-hole attacks

You might be familiar with the terms ‘drive-by download’ and spear-phishing. The former is where cybercriminals look for insecure web sites and plant a malicious script into HTTP or PHP code on one of the web pages. This script may directly install malware onto the computer of someone who visits the site, or it may use an IFRAME to redirect the victim to a malicious site controlled by the cybercriminals. The latter is a targeted form of phishing, often used as the starting-point for a targeted attack. An e-mail is directed to a specific person within a target organization, in the hope that they will click on a link or launch an attachment that runs the attacker’s code and helps them to gain an initial foothold within the company.

When you combine the two approaches (drive-by downloads and spear-phishing) you end up with what’s called a ‘watering-hole’ attack. The attackers study the behavior of people who work for a target organization, to learn about their browsing habits. Then they compromise a web site that is frequently used by employees – preferably one that is run by a trusted organization that is a valuable source of information. Ideally, they will use a zero-day exploit. So when an employee visits a web page on the site, they are infected – typically a backdoor Trojan is installed that allows the attackers to access the company’s internal network. In effect, instead of chasing the victim, the cybercriminal lies in wait at a location that the victim is highly likely to visit – hence the watering-hole analogy.

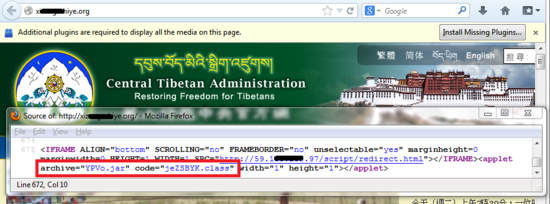

It’s a method of attack that has proved successful for cybercriminals this year. Hard on the heels of our report on the Winnti attacks, we found a Flash Player exploit on a care-giver web site that supports Tibetan refugee children, the ‘Tibetan Homes Foundation’. It turned out that this web site was compromised in order to distribute backdoors signed with stolen certificates from the Winnti case. This was a classic case of a watering-hole attack – the cybercriminals had researched the preferred sites of their victims and compromised them in order to infect their computers. We saw the technique used again in August, when code on the Central Tibetan Administration web site started to redirect Chinese-speaking visitors to a Java exploit that dropped a backdoor used as part of a targeted attack.

Then in September we saw further watering-hole attacks directed against these groups as part of the NetTraveler campaign.

It’s important to note that the watering-hole attack is just one method used by cybercriminals, rather than a replacement for spear-phishing and other methods. And the attacks mentioned above are just part of a series of attacks on Tibetan and Uyghur sites stretching back over two years or more.

Finally, all of these attacks are further testimony to the fact that you don’t need to be a multi-national corporation, or other high-profile organization, to become the victim of a targeted attack.

7. The need to re-forge the weakest link in the security chain

Many of today’s threats are highly sophisticated. This is especially true for targeted attacks, where cybercriminals develop exploit code to make use of unpatched application vulnerabilities, or create custom modules to help them steal data from their victims. However, often the first kind of vulnerability exploited by attackers is the human one. They use social engineering techniques to trick individuals who work for an organization into doing something that jeopardizes corporate security. People are susceptible to such approaches for various reasons. Sometimes they simply don’t realize the danger. Sometimes they’re taken in by the lure of ‘something for nothing’. Sometimes they cut corners to make their lives easier – for example, using the same password for everything.

Many of the high profile targeted attacks that we have analyzed this year have started by ‘hacking the human’. Red October, the series of attacks on Tibetan and Uyghur activists, MiniDuke, NetTraveler and Icefog all employed spear-phishing to get an initial foothold in the organizations they targeted. They frame their approaches to employees using data that they’re able to gather from a company web site, public forums and by sifting through the various snippets of information that people post in social networks. This helps them to generate e-mails that look legitimate and catch people off-guard.

Of course, the same approach is also adopted by those behind the mass of random, speculative attacks that make up the majority of cybercriminal activities – the phishing messages sent out in bulk to large numbers of consumers.

Social engineering can also be applied at a physical level; and this dimension of security is sometimes overlooked. This was highlighted this year in the attempts to install KVM switches in the branches of two British banks. In both cases, the attackers masqueraded as engineers in order to gain physical access to the bank and install equipment that would have let them monitor network activity. You can read about the incidents here and here.

The issue was also highlighted by our colleague, David Jacoby, in September: he conducted a small experiment in Stockholm to see how easy it would be to gain access to business systems by exploiting the willingness of staff to help a stranger in need. You can read David’s report here.

Unfortunately, companies often ignore the human dimension of security. Even if the need for staff awareness is acknowledged, the methods used are often ineffective. Yet we ignore the human factor in corporate security at our peril, since it’s all too clear that technology alone can’t guarantee security. Therefore it’s important for all organizations to make security awareness a core part of their security strategy.

8. Privacy loss: Lavabit, Silent Circle, NSA and the loss of trust

No ITSec overview of 2013 would be complete without mentioning Edward Snowden and the wider privacy implications which followed up to the publication of stories about Prism, XKeyscore and Tempora, as well as other surveillance programs.

Perhaps one of the first visible effects was the shutdown of the encrypted Lavabit e-mail service. We wrote about it here. Silent Circle, another encrypted e-mail provider, decided to shut down their service as well, leaving very few options for private and secure e-mail exchange. The reason why these two services shut down was their inability to provide such services under pressure from Law Enforcement and other governmental agencies.

Another story which has implications over privacy is the NSA sabotage of the elliptic curve cryptographic algorithms released through NIST. Apparently, the NSA introduced a kind of “backdoor” in the Dual Elliptic Curve Deterministic Random Bit Generation (or Dual EC DRBG) algorithm. The “backdoor” supposedly allows certain parties to perform easy attacks against a particular encryption protocol, breaking supposedly secure communications. RSA, one of the major encryption providers in the world noted that this algorithm was default in its encryption toolkit and recommended all their customers to migrate away from it. The algorithm in question was adopted by NIST in 2006, having been available and used on a wide scale at least since 2004.

Interestingly, one of the widely discussed incidents has direct implications for the antivirus industry. In September, Belgacom, a Belgian telecommunications operator announced it was hacked. During a routine investigation, Belgacom staff identified an unknown virus in a number of servers and employee computers. Later, speculations appeared about the origin of the virus and the attack, which pointed towards GCHQ and NSA. Although samples of the malware have not been made available to the security industry, further details appeared which indicate the attack took place through “poisoned” LinkedIn pages that had been booby-trapped through man-in-the-middle techniques, with links pointing to CNE (computer network exploitation) servers.

All these stories about surveillance have also raised questions about the level of cooperation between security companies and governments. The EFF, together with other groups, published a letter on 25th October, asking security vendors a number of questions regarding the detection and blocking of state-sponsored malware.

At Kaspersky Lab, we have a very simple and straightforward policy concerning the detection of malware: We detect and remediate any malware attack, regardless of its origin or purpose. There is no such thing as “right” or “wrong” malware for us. Our research team has been actively involved in the discovery and disclosure of several malware attacks with links to governments and nation-states. In 2012, we published thorough research into Flame and Gauss, two of the biggest nation-state mass-surveillance operations known to date. We have also issued public warnings about the risks of so-called “legal” surveillance tools such as HackingTeam’s DaVinci and Gamma’s FinFisher. It’s imperative that these surveillance tools do not fall into the wrong hands, and that’s why the IT security industry can make no exceptions when it comes to detecting malware. In reality, it is very unlikely that any competent and knowledgeable government organization will request an antivirus developer (or developers) to turn a blind eye to specific state-sponsored malware. It is quite easy for the “undetected” malware to fall into the wrong hands and be used against the very same people who created it.

9. Vulnerabilities and zero-days

Cybercriminals have continued to make widespread use of vulnerabilities in legitimate software to launch malware attacks. They do this using exploits – fragments of code designed to use a vulnerability in a program to install malware on a victim’s computer without the need for any user interaction. This exploit code may be embedded in a specially-crafted e-mail attachment, or it may target a vulnerability in the browser. The exploit acts as a loader for the malware the cybercriminal wishes to install.

Of course, if an attacker exploits a vulnerability is known only to the attacker – a so-called ‘zero-day’ vulnerability – everyone using the vulnerable application will remain unprotected until the vendor has developed a patch that closes up the loophole. But in many cases cybercriminals make successful use of well-known vulnerabilities for which a patch has already been released. This is true for many of the major targeted attacks of 2013 – including Red October, MiniDuke, TeamSpy and NetTraveler. And it’s also true for many of the random, speculative attacks that make up the bulk of cybercrime.

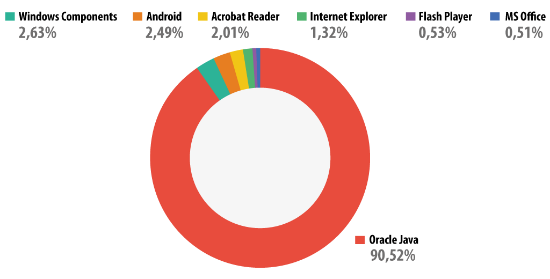

Cybercriminals focus their attention on applications that are widely-used and are likely to remain unpatched for the longest time – giving them a large window of opportunity through which to achieve their goals. In 2013, Java vulnerabilities accounted for around 90.52% of attacks, while Adobe Acrobat Reader accounted for 2.01%. This follows an established trend and isn’t surprising. Java is not only installed on a huge number of computers (3 billion, according to Oracle), but its updates are not installed automatically. Adobe Reader continues to be an application exploited by cybercriminals, though the volume of exploits for this application has reduced greatly over the last 12 months, as a result of Adobe’s more frequent (and, in the latest version, automatic) patch routine.

To reduce their ‘attack surface’, businesses must ensure that they run the latest versions of all software used in the company, apply security updates as they become available and remove software that is no longer needed in the organization. They can further reduce risks by using a vulnerability scanner to identify unpatched applications and by deploying an anti-malware solution that prevents the use of exploits in un-patched applications.

10. The ups and downs of cryptocurrencies – how the Bitcoins rule the world

In 2009, a guy named Satoshi Nakamoto published a paper that would revolutionize the world of e-currencies. Named “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System”, the paper defined the foundations for a distributed, de-centralized financial payment system, with no transaction fees. The Bitcoin system was implemented and people started using it. What kind of people? In the beginning, they were mostly hobbyists and mathematicians. Soon, they were joined by others – mostly ordinary people, but also cybercriminals and terrorists.

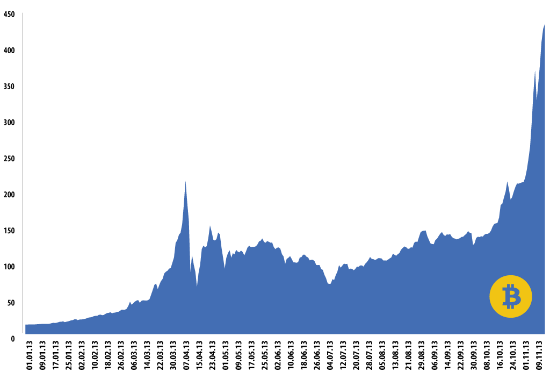

Back in January 2013, the Bitcoin was priced at 13$. As more and more services started adopting the Bitcoin as a means for payment, the price rose. On April 9, 2013, it reached $260 dollars (the average price was $214) before crashing the next day as Bitcoin-rich entities started swapping them for real life money.

Bitcoin daily average price (Mt. Gox)

In November 2013, the Bitcoin started gaining strength again, surpassing the 400$ mark, heading towards 450$ and perhaps above.

So why are Bitcoins so popular? First of all, they provide an almost anonymous and secure means of paying for goods. In the wake of the surveillance stories of 2013, there is perhaps little surprise that people are looking for alternative forms of payment. Secondly, there is perhaps little doubt that they are also popular with cybercriminals, who are looking at ways to evade the law.

In May, we wrote about Brazilian cybercriminals trying to impersonate Bitcoin exchange houses. Bitcoin mining botnets have also appeared, as well as malware designed to steal Bitcoin wallets.

On Friday, October 25, during a joint operation between the FBI and the DEA, the infamous Silk Road was shut down. Silk Road was “a hidden website designed to enable its users to buy and sell illegal drugs and other unlawful goods and services anonymously and beyond the reach of law enforcement”, according to the Press Release from the US Attorney’s Office. It was operating on Bitcoins, which allowed both sellers and customers to remain unknown. The FBI and DEA seized about 140k Bitcoins (worth approximately $56 mil, at today’s rates) from “Dread Pirate Roberts”, Silk Road’s operator. Founded in 2011, Silk Road was operating through the TOR Onion network, having amassed over 9.5 million BTC in sales revenue.

Although it’s clear that cybercriminals have found safe havens in Bitcoins, there are also many other users who have no malicious intentions. As Bitcoin becomes more and more popular, it will be interesting to see if there is any government crackdown on the exchanges in a bid to put a stop to their illicit usage.

If you happen to own Bitcoins, perhaps the most important problem is how to keep them safe. You can find some tips in this post published by our colleagues Stefan Tanase and Sergey Lozhkin.

Conclusions and looking forward: “2014, the year of trust”

Back in 2011, we said the year was explosive. We also predicted 2012 to be revealing and 2013 to be eye opening.

Indeed, some of the revelations of 2013 were eye opening and raised questions about the way we use the Internet nowadays and the category of risks we face. In 2013, advanced threat actors have continued large-scale operations, such as RedOctober or NetTraveler. New techniques have been adopted, such as watering-hole attacks, while zero-days are still popular with advanced actors. We’ve also noticed the emergence of cyber-mercenaries, specialized “for hire” APT groups focusing on hit-and-run operations. Hacktivists were constantly in the news, together with the term “leak”, which is sure to put fear into the heart of any serious sys-admin out there. In the meantime, cybercriminals were busy devising new methods to steal your money or Bitcoins; and ransomware has become almost ubiquitous. Last but not least, mobile malware remains a serious problem, for which no easy solution exists.

Of course, everyone is curious about how all these stories are going to influence 2014. In our opinion, 2014 will be all about rebuilding trust.

Privacy will be a hot subject, with its ups and downs. Encryption will be back in fashion and we believe countless new services will appear, claiming to keep you safe from prying eyes. The Cloud, the wonder child of previous years, is now forgotten as people have lost trust and countries begin thinking more seriously about privacy implications. In 2014, financial markets will probably feel the ripples of the Bitcoin, as massive amounts of money are being pumped in from China and worldwide. Perhaps the Bitcoin will reach the mark of $10,000, or perhaps it will crash and people will start looking for more trustworthy alternatives.

Kaspersky Security Bulletin 2013. Malware Evolution