Q2 in figures

- According to KSN data, Kaspersky Lab products detected and neutralized a total of 983 051 408 threats in the second quarter of 2013.

- Kaspersky Lab solutions detected 577 159 385 attacks launched from online resources located all over the world.

- Kaspersky Lab antivirus programs successfully blocked a total of 400 604 327 attempts to locally infect user computers connected to the Kaspersky Security Network.

- A total of 29 695 new malware modifications targeting mobile devices were detected.

Overview

Cyber Espionage and Targeted Attacks

NetTraveler

In early June, Kaspersky Lab announced a discovery that opened a whole new chapter in the field of cyber-espionage.

Named NetTraveler, this is family of malicious programs used by APT actors to successfully compromise more than 350 high-profile victims in 40 countries. The NetTraveler group infected victims across both the public and private sector including government institutions, embassies, the oil and gas industry, research centers, military contractors and activists.

The threat, which has been active since as early as 2004, is aimed at stealing data related to space exploration, nano-technology, energy production, nuclear power, lasers, medicine and communications.

The attackers infected victims by sending spear-phishing emails with malicious Microsoft Office attachments that are rigged with two commonly exploited vulnerabilities (CVE-2012-0158 and CVE-2010-3333). Even though Microsoft already issued patches for these vulnerabilities, they are still widely used for exploitation in targeted attacks and have proven to be effective.

Data exfiltrated from infected machines typically included file system listings, keylogs, and various types of files including PDFs, Excel spreadsheets, Word documents and files. In addition, the NetTraveler toolkit was able to install additional info-stealing malware as a backdoor, and was customized to steal other types of sensitive information such as configuration details for an application or computer-aided design files.

In conjunction with the C&C data analysis, Kaspersky Lab’s researchers used the Kaspersky Security Network (KSN) to identify additional infection statistics. The top ten countries with victims detected by KSN were Mongolia followed by Russia, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, China, Tajikistan, South Korea, Spain and Germany.

Winnti

In early April, Kaspersky Lab published a detailed report exposing a sustained cyber-espionage campaign conducted by a cybercrime group known as “Winnti”. The Winnti group has been attacking online gaming companies since 2009 and focuses on stealing digital certificates signed by legitimate software vendors in addition to intellectual property theft. The group has also stolen source code for online game projects.

The Trojan used in these attacks is a DLL library compiled for 64-bit Windows environments. It used a properly signed malicious drive and served as a fully functional Remote Administration Tool (RAT) that gives attackers the ability to control a victim’s computer without the user’s knowledge. The finding was significant as this Trojan was the first malicious program on 64-bit versions of Microsoft Windows that had a valid digital signature.

Kaspersky Lab’s experts began analyzing the Winnti group’s campaign and found that more than 30 companies in the online gaming industry had been infected, with the majority being software development companies producing online video games in South East Asia. However, online gaming companies in Germany, the United States, Japan, China, Russia, Brazil, Peru, and Belarus were also identified as victims of the group.

The Winnti group is still active and Kaspersky Lab’s investigation is ongoing.

Winnti follow-up – stolen certs reused in Tibetan & Uyghur attacks

Just one week after we published our report on Winnti, our research team found a Flash Player exploit on a caregiver site that supports Tibetan refugee children. This website was compromised in order to distribute backdoors signed with stolen certificates from the Winnti case.

This was a prime example of a ‘watering hole’ attack, where the attackers researched preferred websites of the victims and compromised them in order to infect their machines. Along with the previously mentioned website, other Tibetan- and Uyghur-related sites were affected and serving “Exploit.SWF.CVE-2013-0634.a”.

Q2 Malware & Hacking Stories

The Carberp story

In March and April this year, members of two different cybercriminal groups were arrested on charges related to bank account theft in Russia and Ukraine.

The arrested groups consisted of both users and allegedly also developers of the Carberp Trojan, which is a classic example for both online banking fraud and establishing hundreds of botnets around the world. The authors were active selling Carberp on underground forums for years, often in a built-to-order fashion and the Trojan even made its way into the mobile world, intercepting transaction authorization numbers (TANs) and sending them via SMS.

In June 2013, a 2 GB archive was released publicly, containing source code from Carberp. While we can observe that the number of attacks using modifications of Carberp is decreasing, unfortunately that is not the entire story. As in previous cases where source code from popular malware was publicly leaked, it’s pretty safe to assume that rival cybercriminals will recycle parts of it to improve their own creations and expand their “market-share” as well as creating their own variants of Carberp, as was the case after Zeus’ source code got leaked in 2011.

Bitcoin madness

The value of Bitcoins has risen dramatically over the last year or so. A unit used to be worth less than one US cent, but the value suddenly skyrocketed into the $130 range. Although the currency may be volatile, its exchange rate continues to grow gradually. Unfortunately, where there’s money to be made, there will be crime, and this applies to Bitcoins as well.

The Bitcoin has established itself as a currency of choice in the criminal underworld due to the fact that it’s harder for law enforcement authorities to trace, making it a more secure, anonymous method of payment.

In April, Kaspersky Lab’s research team discovered a campaign in which cybercriminals used Skype to distribute malware for Bitcoin mining. It used social engineering as the initial threat vector and downloaded further malware to be installed on the victim’s machine. The campaign achieved clicking rates of more than 2000 clicks per hour. Bitcoins mined by the affected machines were then sent to the account of the cybercriminal behind the scam.

One month later, our research team noticed a Brazilian phishing campaign against Bitcoin. Legitimate websites were compromised and iFrames were inserted to launch a Java applet, that in turn redirected users to a fake MtGox website via the malicious use of PAC files. MtGox is a Japanese trading platform for Bitcoin that claims to handle more than 80% of all Bitcoin transactions. The obvious goal of this campaign is to capture the login credentials of the victim and to steal Bitcoins.

Web security and data breaches

The second quarter of 2013 also had its share of data breaches, in which confidential data, including user information, were compromised.

For users, especially those with lots of accounts, the chances of falling foul of a data breach are increasing, with high profile incidents seen every month this quarter.

Some examples included:

Drupal notified its users in late May that hackers managed to get access to usernames, email addresses and hashed passwords. The content management systems developer responded by resetting all passwords as a precaution. Luckily, the passwords were mostly stored in a hashed and salted fashion. The breach was found during a security audit and involved an exploit in vulnerable third-party software installed on their web portal. According to Drupal, credit card information was not compromised.

On 19 June, the web browser Opera was delivering malicious browser updates to its users after its internal network was compromised and a code signing certificate stolen. Even though the certificate had already expired at the time of the attack, it could still result in successful infections, as not all versions of Windows are handling certificate checks thoroughly enough. Despite the short time in which the malicious payload was active, several thousand Opera users could have received the malicious update. Kaspersky Lab detects the Trojan with keylogging and data-stealing capabilities used in this attack as Trojan-PSW.Win32.Tepfer.msdu.

Botnet Specials

Botnet attacks WordPress installations

In the beginning of April, GatorHost spread the word about a botnet counting over 90,000 unique IP addresses that was used to launch a global brute force attack on WordPress installations. It is assumed that the goal of the attack was to place a backdoor onto the servers to include them in the existing botnet. In some cases the infamous BlackHole Exploit kit was successfully planted.

Gaining access to WordPress servers and abusing them is a boon for cybercriminals because of the higher bandwidth and performance compared to most desktop machines. There is also the added possibility of further distributing malware via established blogs with regular readers.

IRC botnet strikes unpatched Plesk vulnerability

Two months after WordPress installations were attacked by a botnet, researchers found an IRC botnet exploiting a vulnerability in Plesk, the widely used hosting control panel. Exploiting this vulnerability (CVE-2012-1823) resulted in remote code execution with the rights of the Apache user. The vulnerability affected Plesk 9.5.4 and earlier versions. According to Ars Technica, more than 360,000 installations were at risk.

The IRC botnet was infecting vulnerable web servers with a backdoor that connected to the C&C server. Interestingly, the C&C server itself was susceptible to the very same Plesk vulnerability. Researchers used this vulnerability to monitor the botnet and found that about 900 infected webservers were trying to connect. A tool was written to disinfect the zombie servers and make the new botnet vanish.

Mobile Malware Still on the Rise

Steady rise of quantity, quality and diversity

Android has established itself as the cybercriminal’s target of choice when it comes to mobile operating systems and can be considered the mobile world’s equivalent to Windows.

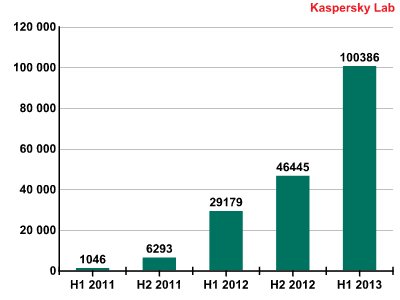

Virtually all mobile samples that were discovered in the mobile realm were targeting Android in Q2 – just like in the first quarter of the year. One remarkable milestone was reached right at the end of the quarter – on 30 June the 100,000 modifications barrier (consisting of 629 malware families) was broken.

Please note that we’re not counting individual malicious apps, but malicious code samples. These code samples, however, are mostly used in multiple Trojanized apps, resulting in a significantly higher number of malicious apps waiting to be downloaded. The common procedure for cybercriminals is to download legitimate apps, adding malicious code and using them as a vehicle for distribution. The repackaged apps are then uploaded again, especially to third-party app stores. Popular apps are targeted to abuse their reputation, since users are actively searching for them and this therefore makes life easier for cybercriminals.

Statistically, the second quarter saw a steady increase from the first, with a total of 29,695 modifications (Q1 2013: 22,749). April saw 7,141 modifications, representing the lowest value in Q2. In both May and June, however, Kaspersky Lab detected more than 11,000 modifications – 11,399 and 11,155 respectively. Overall, 2013 has seen a massive leap in terms of the number of new mobile modifications.

Number of samples in our collection

While the most prevalent mobile species in attack figures has traditionally been SMS-Trojans, its respective share in our collection sample base shows a different picture.

First place goes to Backdoors with a share of 32.3%, followed by Trojans (23.2%) and SMS-Trojans. Trojan-Spies are ranked fourth with 4.9%. In terms of capabilities and flexibility, the trend of mobile malware converges with malware from the PC landscape. Modern samples make use of obfuscation technologies to evade analysis and frequently carry multiple payloads to make the infection more persistent, exfiltrate additional information or download and install additional malware.

Obad – the most sophisticated Android Trojan ever

In Q2 2013 we detected what is probably the most sophisticated Android Trojan so far. It can send SMS messages to premium numbers, download and install other malware on the infected device and/or send it via Bluetooth, as well as remotely perform commands from the console. Kaspersky Lab products detect the malicious program as Backdoor.AndroidOS.Obad.a.

The creators of Backdoor.AndroidOS.Obad.a have found a flaw in the popular dex2jar program used by analysts to convert APK files to the JAR format, which is easier to work with and analyze. The vulnerability discovered by the cybercriminals disrupts the conversion of Dalvik bytecode to Java bytecode, making it more difficult to perform static analysis on the Trojan.

The cybercriminals also discovered an Android OS error related to parsing the file AndroidManifest.xml, which is present in every Android application and is used to describe the application’s structure, define its launch parameters etc. The malware writers have modified AndroidManifest.xml in such a way that it does not comply with the standard defined by Google but, due to the vulnerability, is correctly parsed on the smartphone. This greatly complicates dynamic analysis of the Trojan.

Those who created Backdoor.AndroidOS.Obad.a took advantage of yet another previously unknown flaw in Android OS, which enables a malicious program to gain extended Device Administrator privileges without being listed among the applications having such privileges. This makes it impossible to remove the malware from the mobile device.

Overall, the malicious program exploits three previously unpublished vulnerabilities. We have never encountered anything like it before in mobile malware.

The extended Device Administrator privileges can be used by the Trojan to block the device’s screen briefly (for no more than 10 seconds). This typically happens after connecting to free Wi-Fi or activating Bluetooth, which can be used by the malware to send copies of itself and other malicious applications to other devices nearby. It is possible that Backdoor.AndroidOS.Obad.a does this as an attempt to keep the user from noticing malicious activity.

To send information about an infected device and the ‘work’ performed, Backdoor.AndroidOS.Obad.a uses the internet connection that is currently active. If no connection is available, the Trojan searches for nearby Wi-Fi networks that do not require authentication and connects to one of the networks it finds.

After the first launch, the malicious application collects the Bluetooth device’s MAC address, operator name, phone number and IMEI, account balance, local time and information on whether Device Administrator or superuser (root) privileges have been obtained. All of the above information is sent to the command server. The malware also provides the command server with up-to-date tables of premium numbers and prefixes for sending SMS messages, a list of tasks and a list of C&C (command) servers. During the first communication session, an empty table and C&C list is sent to the command server; in the course of the session the Trojan may get an updated table of premium numbers and a new C&C address list.

Cybercriminals can control the Trojan with text messages: the Trojan can receive key strings defining certain actions (key_con, key_url, key_die) from the server; it will then search incoming text messages for these key strings. Each incoming message is checked for the presence of any one of the key strings. If a key has been found, the corresponding action is performed: key_con – connect to the server immediately; key_die – remove tasks from the database; key_url – switch to a different C&C server (the text should include the new C&C address). This enables the cybercriminals to create a new C&C server and send its address by SMS with a key_url key, after which all the infected devices will switch to the new server.

The Trojan receives commands from the C&C and enters them into a database. Each record in the database contains the command number, the execution time specified by the server and its parameters. The list of actions that can be performed by the Trojan after receiving commands is provided below:

- Send a text message. Parameters include the target number and the text to be sent. Replies are deleted;

- Ping;

- Get balance via USSD;

- Operate as a proxy server;

- Connect to the specified address;

- Download and install a file from the server;

- Send the server a list of applications installed on the device;

- Send information about an application specified by the command server;

- Send the user’s contacts to the server;

- Remote Shell. Perform commands specified by the cybercriminal from the console;

- Send a file to all Bluetooth devices discovered.

FakeDefender: ransomware for Android

In June, the word spread that ransomware had reached mobile devices, or more precisely, a crossover between fakeAV and ransomware. The associated app is called “Free Calls Update”. After it is installed and launches the app tries to gain device administrator rights in order to change settings on the device and switch on/off Wi-Fi and 3G Internet. The installation file will be deleted after the installation, in an attempt to hinder genuine anti-malware software if it’s installed on the system. The app itself is a fake-AV which pretends to scan for malware and shows non-existent malware and prompts the victim to buy a license to obtain the full version – a ploy that has already been adopted on PCs for some time now.

While browsing, the app shows a pop-up window, scaring the user by warning that malware is trying to steal pornographic content from the phone; this note is persistent and locks up the whole device. If device administrator rights have been granted, any attempts to delete the app or launch other apps are denied by FakeDefender.

Statistics

All the statistics used in this report were obtained from the cloud-based Kaspersky Security Network (KSN). The statistics were collected from KSN users who consented to share their local data. Millions of users of Kaspersky Lab products in 213 countries take part in the global information exchange on malicious activity.

Online threats

The statistics in this section were derived from web antivirus components which protect users when malicious code attempts to download from infected websites. Infected websites might be created by malicious users, or they could also be made up of user-contributed content (such as forums) and legitimate resources that have been hacked.

Online threat detection

In the second quarter this year, Kaspersky Lab products detected 577 159 385 attacks launched from online resources around the world.

The Top 20 detectable online threats

| Rank | Name* | % of all attacks** |

| 1 | Malicious URL | 91.52% |

| 2 | Trojan.Script.Generic | 3.61% |

| 3 | Trojan.Script.Iframer | 0.80% |

| 4 | AdWare.Win32.MegaSearch.am | 0.54% |

| 5 | Exploit.Script.Blocker | 0.41% |

| 6 | Trojan-Downloader.Script.Generic | 0.27% |

| 7 | Exploit.Java.Generic | 0.16% |

| 8 | Trojan.Win32.Generic | 0.16% |

| 9 | Exploit.Script.Blocker.u | 0.12% |

| 10 | AdWare.Win32.Agent.aece | 0.11% |

| 11 | Trojan-Downloader.JS.JScript.cb | 0.11% |

| 12 | Trojan.JS.FBook.q | 0.10% |

| 13 | Trojan-Downloader.Win32.Generic | 0.09% |

| 14 | Exploit.Script.Generic | 0.08% |

| 15 | Trojan-Downloader.HTML.Iframe.ahs | 0.05% |

| 16 | Packed.Multi.MultiPacked.gen | 0.05% |

| 17 | Trojan-Clicker.HTML.Iframe.bk | 0.05% |

| 18 | Trojan.JS.Iframe.aeq | 0.04% |

| 19 | Trojan.JS.Redirector.xb | 0.04% |

| 20 | Exploit.Win32.CVE-2011-3402.a | 0.04% |

*These statistics represent detection verdicts of the web-based antivirus module and were submitted by the users of Kaspersky Lab products who consented to share their local data.

**The percentage of unique incidents recorded by web-based antivirus on user computers.

First place in the Q2 2013 Top 20 Detectable Threats was taken once again by denylisted malicious links. Their percentage increased by 0.08% from the first quarter of the year, and ultimately represented 91.55% of all web-based antivirus detections.

Verdicts identifying Trojan.Script.Generic (2nd place) and Trojan.Script.Iframer (3rd place) were still in the Top 5 detectable threats this past quarter. These threats are blocked during attempted drive-by attacks, which are currently one of the most common methods used to attack user computers. The percentage of Trojan.Script.Generic detections rose 0.82%, while Trojan.Script.Iframer was up by 0.07%.

In Q2 2013, nearly all of the Top 20 threats that can be detected by web antivirus components were malicious programs that are somehow involved in drive-by attacks.

Countries where online resources are seeded with malware

This indicator highlights the countries where websites which are seeded with malicious programs are physically located. In order to determine the geographical source of web-based attacks, a method was used by which domain names are matched up against actual domain IP addresses, and then the geographical location of a specific IP address (GEOIP) is established.

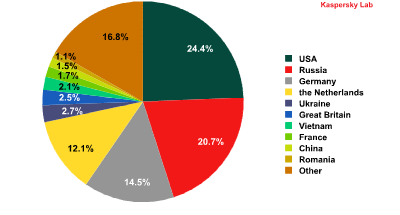

Some 83% of online resources used to spread malicious programs are located in 10 countries. In Q2 2013, this number was up by 2%.

The distribution of online resources seeded with malicious programs in Q2 2013.

The countries with the largest number of malicious hosting services changed just slightly since the first quarter of the year. While the US (24.4%) and Russia (20.7%) held on to their leading positions, Ireland dropped out of the Top 10, and was replaced by Vietnam in seventh place, with 2.1%.

Countries where users face the greatest risk of online infection

In order to assess the risk level for online infection faced by users in different countries, we calculated just how often users with Kaspersky Lab products encountered web-based antivirus detections over the course of the past three months.

| Rank | Country | % |

| 1 | Armenia | 53.92% |

| 2 | Russia | 52.93% |

| 3 | Kazakhstan | 52.82% |

| 4 | Tajikistan | 52.52% |

| 5 | Azerbaijan | 52.38% |

| 6 | Vietnam | 47.01% |

| 7 | Moldova | 44.80% |

| 8 | Belarus | 44.68% |

| 9 | Ukraine | 43.89% |

| 10 | Kyrgyzstan | 42.28% |

| 11 | Georgia | 39.83% |

| 12 | Uzbekistan | 39.04% |

| 13 | Sri Lanka | 36.33% |

| 14 | Greece | 35.75% |

| 15 | India | 35.47% |

| 16 | Thailand | 34.97% |

| 17 | Austria | 34.85% |

| 18 | Turkey | 34.74% |

| 19 | Libya | 34.40% |

| 20 | Algeria | 34.10% |

The Top 20 countries* with the highest levels of infection risk** in Q2 2013

*For the purposes of these calculations, we excluded countries where the number of Kaspersky Lab product users is relatively small (less than 10,000).

**The percentage of unique users in the country with computers running Kaspersky Lab products that blocked web-borne threats.

The Top 10 countries where users most frequently encounter malicious programs are almost completely comprised of countries from the former Soviet Union, with the exception of Vietnam. Russia (52.9%) ranked second in Q2. The second quarter of the year also brought some newcomers to this Top 20: Libya (34.4%), Austria (34.9%), and Thailand (35%).

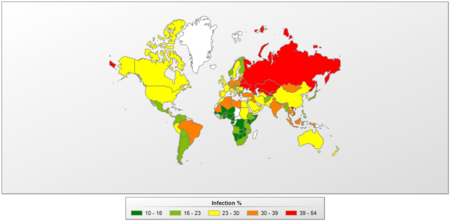

All of the countries can be divided into four basic groups.

- No countries qualified for the maximum risk group (countries where over 60% of users encountered an online threat at least once) this past quarter.

- High risk. The first ten countries from the Top 20 were in this group (three fewer than in Q1 2013). They include Vietnam and countries from the FSU, specifically Armenia (53.9%), Russia (52.9%), Kazakhstan (52.8%), Moldova (44.8%), Belarus (44.7%) and Ukraine (43.9%).

- Moderate risk. This group includes countries where 21-40.9% of all users encountered at least one online threat, and included 82 countries in the second quarter this year. These include Italy (29.2%), Germany (33.7%), France (28.5%), Sudan (28.2%), Spain (28.4%), Qatar (28.2%), the US (28.6%), Ireland (27%), the UK (28.3%), the UAE (25.6%), and the Netherlands (21.9%).

- Low risk. In Q2 2013, this group included 52 countries with percentages ranging from 9 to 20.9%. The lowest numbers (under 20%) of web-based attacks were in African countries, where the Internet is still underdeveloped. The exceptions were Denmark (18.6%) and Japan (18.1%).

The risk of online infection around the world in Q2 2013

An average of 35.2% of computers connected to KSN were subjected to at least one attack while surfing the web during the past three months — a 3.9% increase from the first quarter this year.

Local threats

This section contains an analysis of statistics based on data obtained from the on-access scanner and scanning statistics for different disks, including removable media.

Threats detected on user computers

In Q2 2013, Kaspersky Lab’s antivirus solutions successfully blocked 400 604 327 attempted local infections on user computers participating in the Kaspersky Security Network.

The Top 20 threats detected on user computers

| Rank | Name | % of individual users* |

| 1 | DangerousObject.Multi.Generic | 34.47% |

| 2 | Trojan.Win32.Generic | 28.69% |

| 3 | Trojan.Win32.AutoRun.gen | 21.18% |

| 4 | Virus.Win32.Sality.gen | 13.19% |

| 5 | Exploit.Win32.CVE-2010-2568.gen | 10.97% |

| 6 | AdWare.Win32.Bromngr.i | 8.89% |

| 7 | Trojan.Win32.Starter.lgb | 8.03% |

| 8 | Worm.Win32.Debris.a | 6.53% |

| 9 | Virus.Win32.Generic | 5.30% |

| 10 | Trojan.Script.Generic | 5.11% |

| 11 | Virus.Win32.Nimnul.a | 5.10% |

| 12 | Net-Worm.Win32.Kido.ih | 5.07% |

| 13 | HiddenObject.Multi.Generic | 4.79% |

| 14 | Net-Worm.Win32.Kido.ir | 4.27% |

| 15 | Exploit.Java.CVE-2012-1723.gen | 3.91% |

| 16 | AdWare.Win32.Yotoon.e | 3.62% |

| 17 | AdWare.JS.Yontoo.a | 3.61% |

| 18 | DangerousPattern.Multi.Generic | 3.60% |

| 19 | Trojan.Win32.Starter.lfh | 3.52% |

| 20 | Trojan.WinLNK.Runner.ea | 3.50% |

These statistics are compiled from malware detection verdicts generated by the on-access and on-demand scanner modules on the computers of those users running Kaspersky Lab products that have consented to submit their statistical data.

* The proportion of individual users on whose computers the antivirus module detected these objects as a percentage of all individual users of Kaspersky Lab products on whose computers a malicious program was detected.

As before, there are three clear leaders of this Top 20.

Malicious programs classified as DangerousObject.Multi.Generic detected using cloud technologies ranked in first place with 34.47% — that’s almost double the percentage recorded in Q1. Cloud technologies work when there are still no signatures in antivirus databases, and no heuristics for detecting malicious programs, but Kaspersky Lab’s cloud already has data about the threat. This is essentially how the newest malicious programs are detected.

The threat Trojan.Win32.Generic ranked second (28.69%) based on verdicts issued by the heuristic analyzer in the proactive detection of numerous malicious programs. Trojan.Win32.AutoRun.gen (21.18%) ranked third, and includes malicious programs that use the autorun feature.

Countries where users face the highest risk of local infection

The figures below show the average rate of infection among user computers in different countries. KSN participants who provide Kaspersky Lab with information had at least one malicious file detected on nearly every third (29.9%) computer – either on their hard drive or a removable disk connected to the computer. That’s 1.5% lower than last quarter.

| Rank | Country | % |

| 1 | Vietnam | 59.88% |

| 2 | Bangladesh | 58.66% |

| 3 | Nepal | 54.20% |

| 4 | Mongolia | 53.54% |

| 5 | Afghanistan | 51.79% |

| 6 | Sudan | 51.58% |

| 7 | Algeria | 50.49% |

| 8 | India | 49.46% |

| 9 | Pakistan | 49.45% |

| 10 | Cambodia | 48.82% |

| 11 | Laos | 48.60% |

| 12 | The Maldives | 47.70% |

| 13 | Djibouti | 47.07% |

| 14 | Iraq | 46.91% |

| 15 | Mauritania | 45.71% |

| 16 | Yemen | 45.23% |

| 17 | Indonesia | 44.52% |

| 18 | Egypt | 44.42% |

| 19 | Morocco | 43.98% |

| 20 | Tunisia | 43.95% |

Computer infection levels* by country — Q2 2013 Top 20**

* The percentage of unique users in the country with computers running Kaspersky Lab products that blocked web-borne threats.

** When calculating, we excluded countries where there are fewer than 10,000 Kaspersky Lab users.

For the fifth consecutive quarter, the Top 20 positions in this category were held by countries in Africa, the Middle East, and South East Asia. Vietnam ranked first in terms of the percentage of computers with blocked malicious code (59.9%), and Bangladesh, which was in first place last quarter, was a close second this time around with 58.7%, or 9.1 percentage points lower than in Q1 2013.

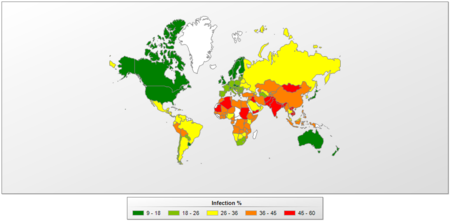

Local infection rates can also be broken down into four groups based on risk level:

- Maximum local infection rate (over 60%). Happily, no countries qualified for this category during the past three months.

- High local infection rate (41-60%). A total of 34 countries in Q2 2013, including Vietnam (59.9%), Bangladesh (58.7%), Nepal (54.2%), India (49.5%), and Iran (42.6%).

- Moderate local infection rate (21-40.9%). A total of 77 countries, including: Lebanon (40%), China (36.7%), Qatar (34.1%), Russia (30.5%), Ukraine (30.1%), Spain (23.9%), Italy (21.2%), and Cyprus (21.6%).

- Low local infection rate (under 21%). A total of 33 countries, including: France (19.6%), Belgium (17.5%), the US (17.9%), the UK (17.5%), Australia (17.5%), Germany (18.5%), Estonia (15.2%), the Netherlands (14.6%), Sweden (12.1%), Denmark (9.7%), and Japan (9.1%).

The risk of local infection around the world — Q2 2013

The Top 10 countries with the lowest risk of local infection were:

| Rank | Country | % |

| 1 | Japan | 9.01% |

| 2 | Denmark | 9.72% |

| 3 | Finland | 11.83% |

| 4 | Sweden | 12.10% |

| 5 | Czech Republic | 12.78% |

| 6 | Martinique | 13.94% |

| 7 | Norway | 14.22% |

| 8 | Ireland | 14.47% |

| 9 | The Netherlands | 14.55% |

| 10 | Slovenia | 14.70% |

In Q2 2013, two new countries appeared in this Top 10 — Martinique and Slovenia, pushing out Switzerland and New Zealand.

IT Threat Evolution: Q2 2013