Today, we are announcing the release of KTAE, the Kaspersky Threat Attribution Engine. This code attribution technology, developed initially for internal use by the Kaspersky Global Research and Analysis Team, is now being made available to a wider audience. You can read more about KTAE in our official press release, or go directly to its info page on the Kaspersky Enterprise site. From an internal tool, to prototype and product, this is a road which took about 3 years. We tell the story of this trip below, while throwing in a few code examples as well. However, before diving into KTAE, it’s important to talk about how it all started, on a sunny day, approximately three years ago.

May 12, 2017, a Friday, started in a very similar fashion to many other Fridays: I woke up, made coffee, showered and drove to work. As I was reading e-mails, one message from a colleague in Spain caught my attention. Its subject said “Crisis … (and more)”. Now, crisis (and more!) is not something that people appreciate on a Friday, and it wasn’t April 1st either. Going through the e-mail from my colleague, it became obvious something was going on in several companies around the world. The e-mail even had an attachment with a photo, which is now world famous:

Soon after that, Spain’s Computer Emergency Response Team CCN-CERT, posted an alert on their site about a massive ransomware attack affecting several Spanish organizations. The alert recommended the installation of updates in the Microsoft March 2017 Security Bulletin as a means of stopping the spread of the attack. Meanwhile, the National Health Service (NHS) in the U.K. also issued an alert and confirmed infections at 16 medical institutions.

As we dug into the attack, we confirmed additional infections in several additional countries, including Russia, Ukraine, and India.

Quite essential in stopping these attacks was the Kaspersky System Watcher component. The System Watcher component has the ability to rollback the changes done by ransomware in the event that a malicious sample manages to bypass other defenses. This is extremely useful in case a ransomware sample slips past defenses and attempts to encrypt the data on the disk.

As we kept analysing the attack, we started learning more things; for instance, the infection relied on a famous exploit, (codenamed “EternalBlue”), that has been made available on the internet through the Shadowbrokers dump on April 14th, 2017 and patched by Microsoft on March 14. Despite the fact the patch has been available for two months, it appeared that many companies didn’t patch. We put together a couple of blogs, updated our technical support pages and made sure all samples were detected and blocked even on systems that were vulnerable to the EternalBlue exploit.

- WannaCry ransomware used in widespread attacks all over the world

- WannaCry FAQ: What you need to know today

Meanwhile, as everyone was trying to research the samples, we were scouting for any possible links to known criminal or APT groups, trying to determine how a newcomer malware was able to cause such a pandemic in just a few days. The explanation here is simple – for ransomware, it is not very often that we get to see completely new, built from scratch, pandemic-level samples. In most cases, ransomware attacks make use of some popular malware that is sold by criminals on underground forums or, “as a service”.

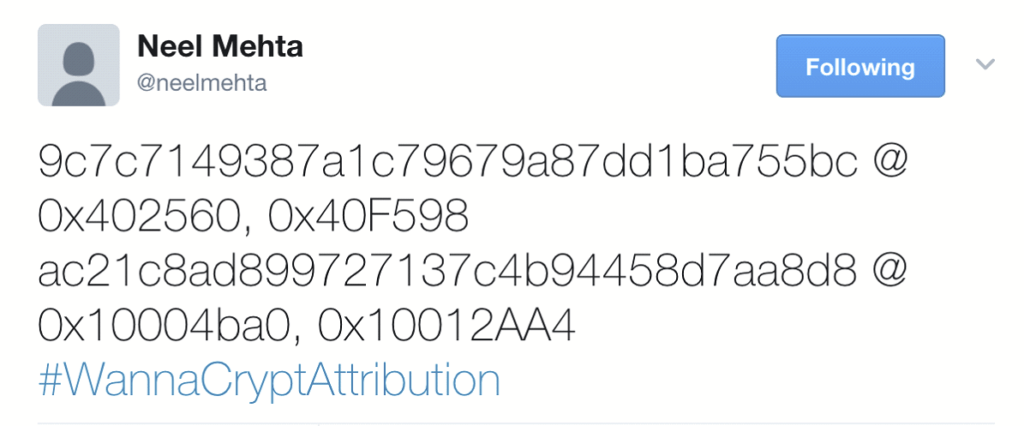

And yet, we couldn’t spot any links with known ransomware variants. Things became a bit clearer on Monday evening, when Neel Mehta, a researcher at Google, posted a mysterious message on Twitter with the #WannaCryptAttribution hashtag:

The cryptic message in fact referred to a similarity between two samples that have shared code. The two samples Neel refers to in the post were:

- A WannaCry sample from February 2017 which looks like a very early variant

- A Lazarus APT group sample from February 2015

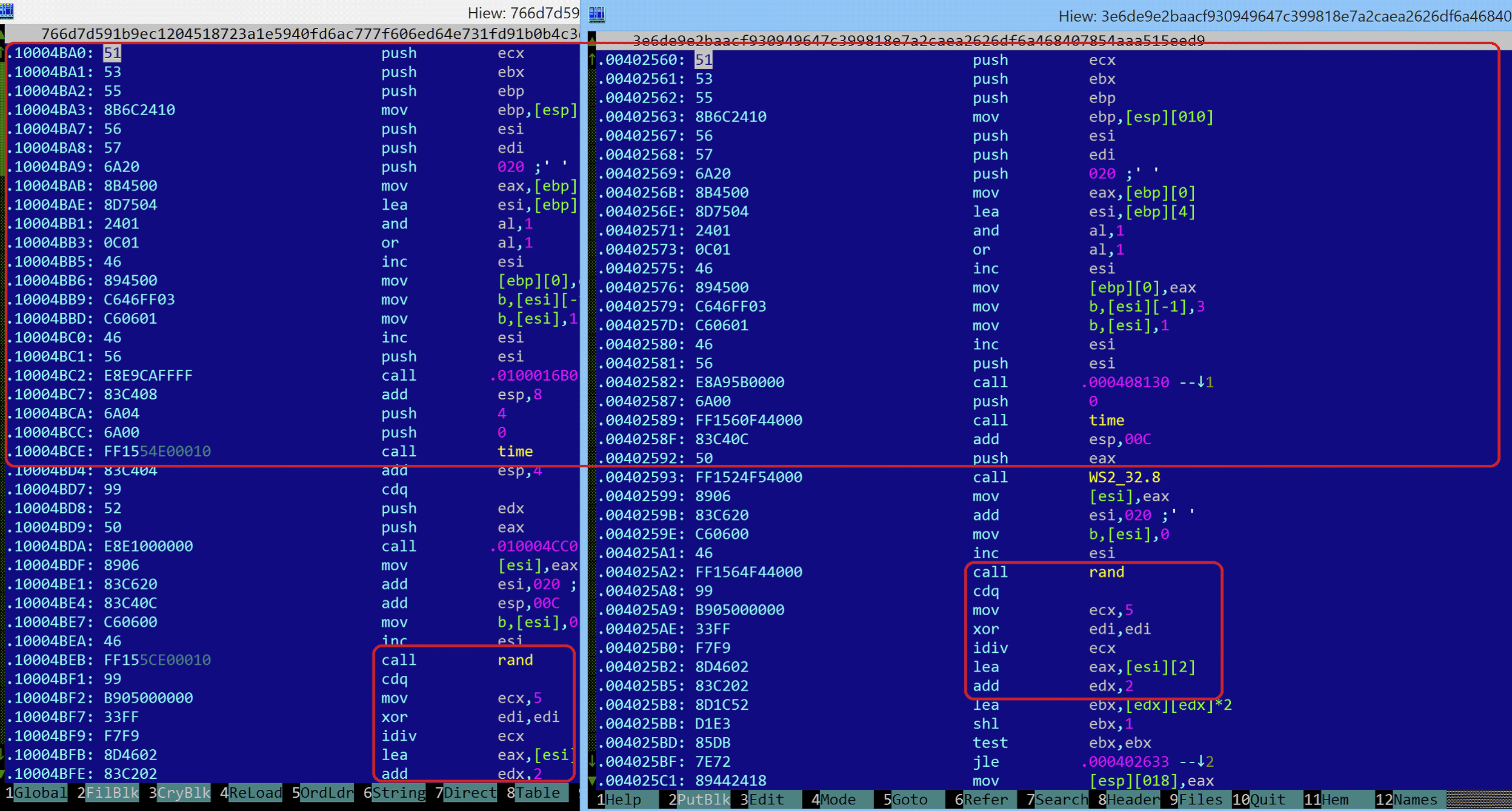

The similarity can be observed in the screenshot below, taken between the two samples, with the shared code highlighted:

Although some people doubted the link, we immediately realized that Neel Mehta was right. We put together a blog diving into this similarity, “WannaCry and Lazarus Group – the missing link?”. The discovery of this code overlap was obviously not a random hit. For years, Google integrated the technology they acquired from Zynamics into their analysis tools making it possible to cluster together malware samples based on shared code. Obviously, the technology seemed to work rather nicely. Interestingly, one month later, an article was published suggesting the NSA also reportedly believed in this link.

Thinking about the story, the overlap between WannaCry and Lazarus, we put a plan together – what if we built a technology that can quickly identify code reuse between malware attacks and pinpoint the likely culprits in future cases? The goal would be to make this technology available in a larger fashion to assist threat hunters, SOCs and CERTs speed up incident response or malware triage. The first prototype for this new technology was available internally June 2017, and we continued to work on it, fine-tuning it, over the next months.

In principle, the problem of code similarity is relatively easy. Several approaches have been tested and discussed in the past, including:

- Calculating checksums for subs and comparing them against a database

- Reconstructing the code flow and creating a graph from it; comparing graphs for similar structures

- Extracting n-grams and comparing them against a database

- Using fuzzy hashes on the whole file or parts of it

- Using metadata, such as the rich header, exports or other parts of the file; although this isn’t code similarity, it can still yield some very good results

To find the common code between two malware samples, one can, for instance, extract all 8-16 byte strings, then check for overlaps. There’s two main problems to that though:

- Our malware collection is too big; if we want to do this for all the files we have, we’d need a large computing cluster (read: thousands of machines) and lots of storage (read: Petabytes)

- Capex too small

Additionally, doing this massive code extraction, profiling and storage, not to mention searching, in an efficient way that we can provide as a stand-alone box, VM or appliance is another level of complexity.

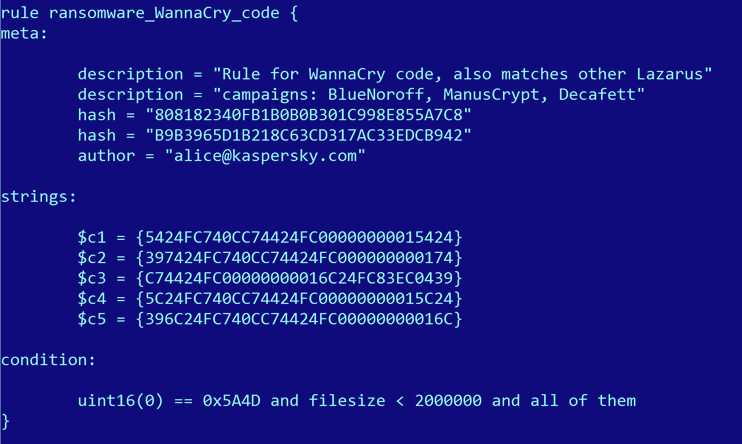

To refine it, we started experimenting with code-based Yara rules. The idea was also simple and beautiful: create a Yara rule from the unique code found in a sample, then use our existing systems to scan the malware collection with that Yara rule.

Here’s one such example, inspired by WannaCry:

This innocent looking Yara rule above catches BlueNoroff (malware used in the Bangladesh Bank Heist), ManusCrypt (a more complex malware used by the Lazarus APT, also known as FALLCHILL) and Decafett, a keylogger that we previously couldn’t associate with any known APT.

A breakthrough in terms of identifying shared code came in Sep 2017, when for the first time we were able to associate a new, “unknown” malware with a known entity or set of tools. This happened during the #CCleaner incident, which was initially spotted by Morphisec and Cisco Talos.

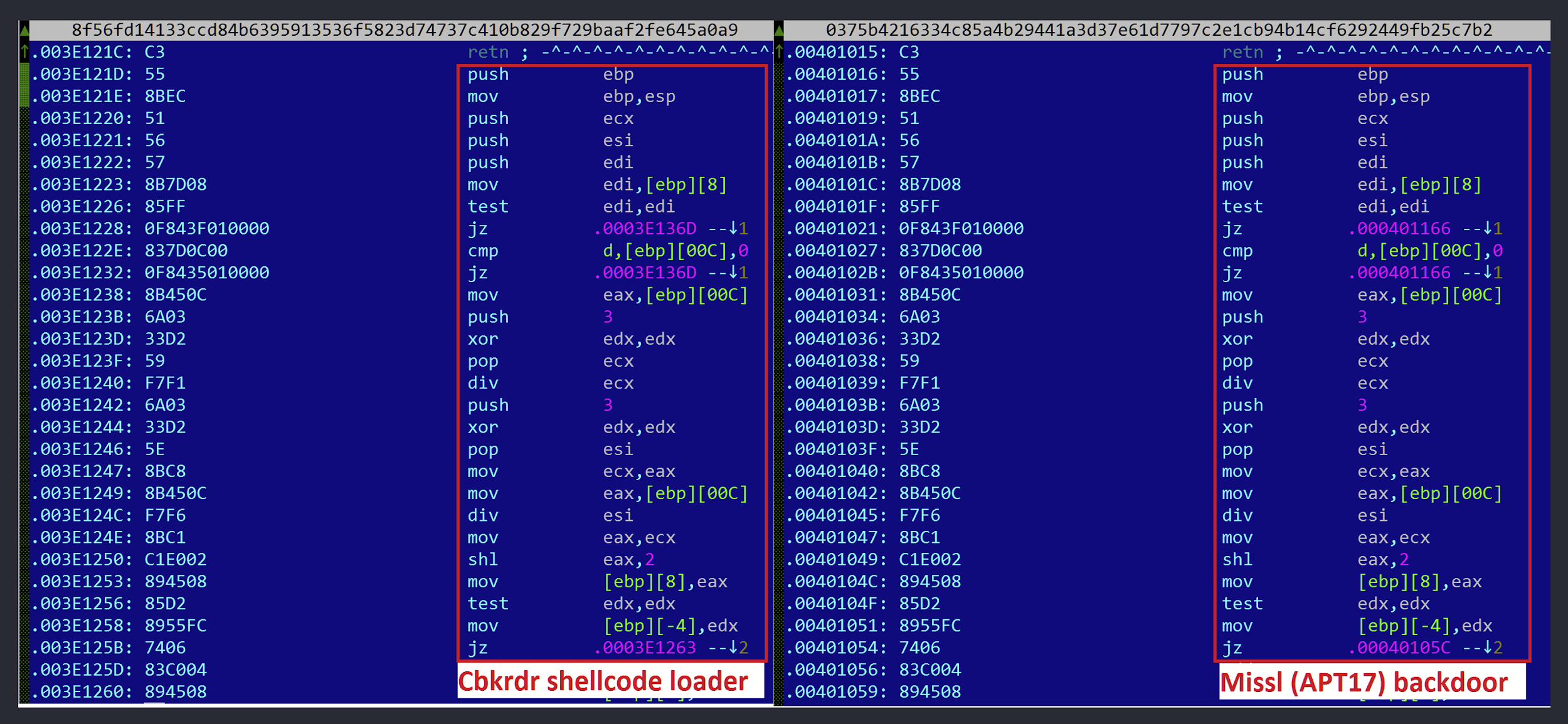

In particular, our technology spotted a fragment of code, part of a custom base64 encoding subroutine, in the Cbkrdr shellcode loader that was identical to one seen in a previous malware sample named Missl, allegedly used by APT17:

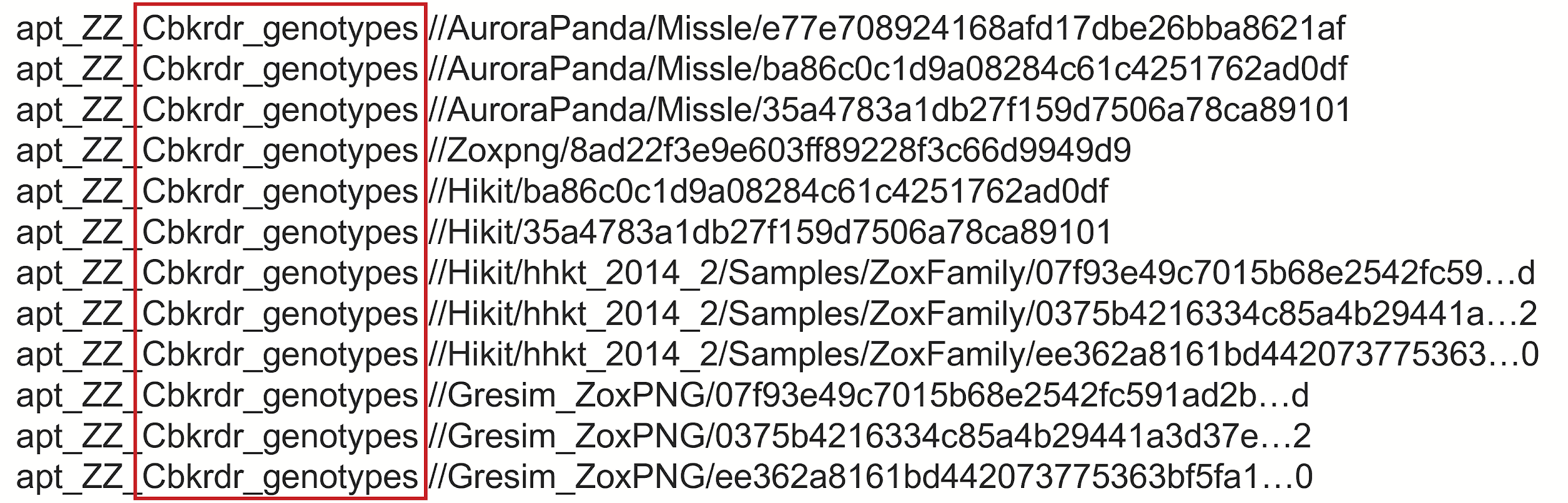

Digging deeper, we identified at least three malware families that shared this code: Missl, Zoxpng/Gresim and Hikit, as shown below in the Yara hits:

In particular, the hits above are the results of running a custom Yara rule, based on what we call “genotypes” – unique fragments of code, extracted from a malware sample, that do not appear in any clean sample and are specific to that malware family (as opposed to being a known piece of library code, such as zlib for instance).

As a side note, Kris McConkey from PwC delivered a wonderful dive into Axiom’s tools during his talk “Following APT OpSec failures” at SAS 2015 – highly recommended if you’re interested in learning more about this APT super-group.

Soon, the Kaspersky Threat Attribution Engine – “KTAE” – also nicknamed internally “Yana”, became one of the most important tools in our analysis cycle.

Digging deeper, or more case studies

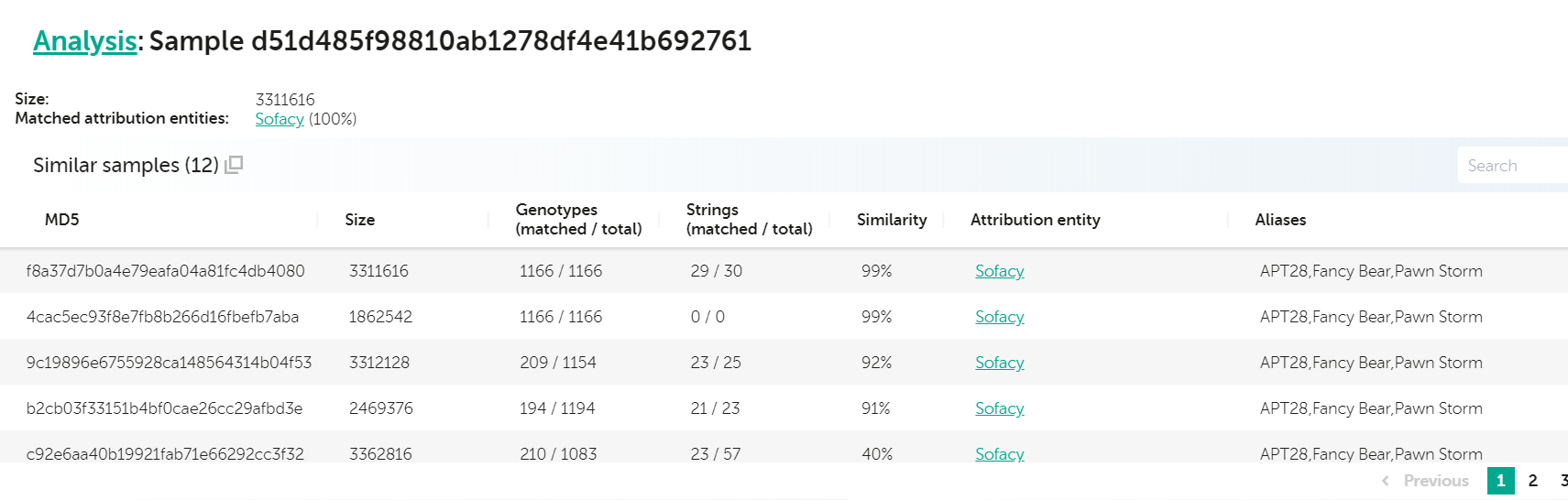

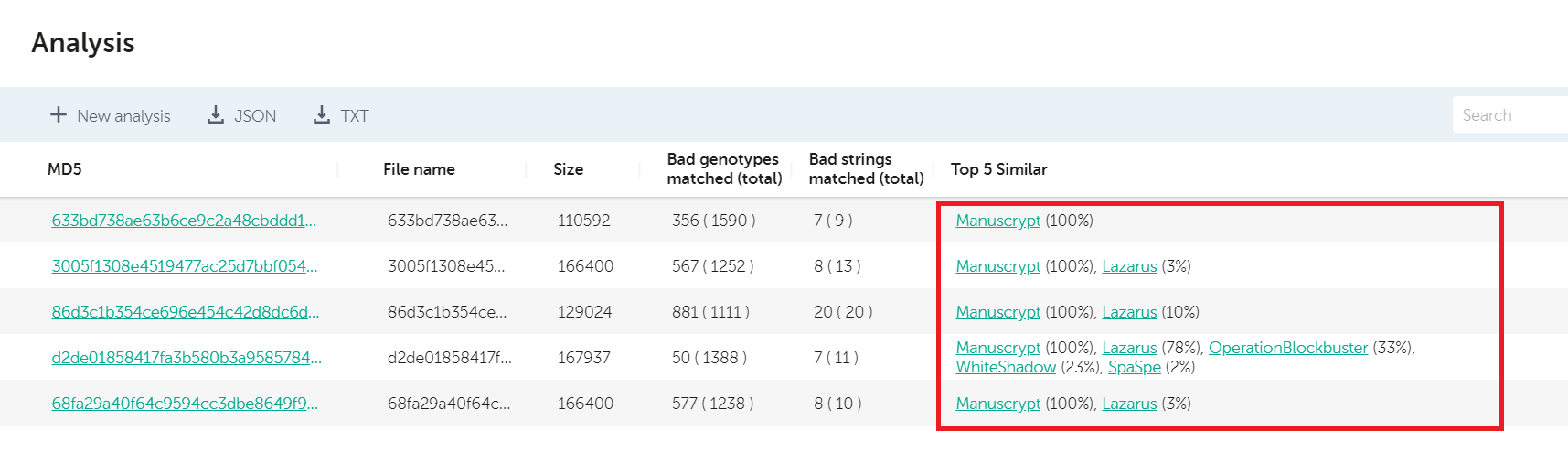

The United States Cyber Command, or in short, “USCYBERCOM”, began posting samples to VirusTotal in November 2018, an excellent move in our opinion. The only drawback for these uploads was the lack of any context, such as the malware family, if it’s APT or criminal, which group uses them and whether they were found in the wild, or scooped from certain places. Although the first upload, a repurposed Absolute Computrace loader, wasn’t much of an issue to recognize, an upload from May 2019 was a bit more tricky to identify. This was immediately flagged as Sofacy by our technology, in particular, as similar to known XTunnel samples, a backdoor used by the group. Here’s how the KTAE report looks like for the sample in question:

Analysis for d51d485f98810ab1278df4e41b692761

In February 2020, USCYBERCOM posted another batch of samples that we quickly checked with KTAE. The results indicated a pack of different malware families, used by several APT groups, including Lazarus, with their BlueNoroff subgroup, Andariel, HollyCheng, with shared code fragments stretching back to the DarkSeoul attack, Operation Blockbuster and the SPE Hack.

Going further, USCYBERCOM posted another batch of samples in May 2020, for which KTAE revealed a similar pattern.

Of course, one might wonder, what else can KTAE do except help with the identification of VT dumps from USCYBERCOM?

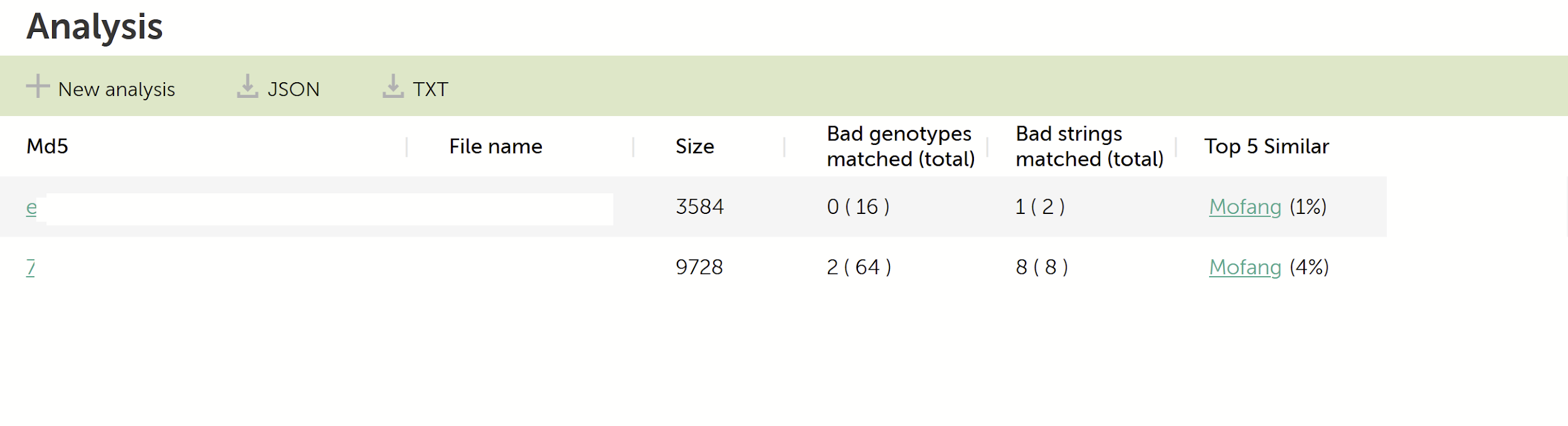

For a more practical check, we looked at the samples from the 2018 SingHealth data breach that, according to Wikipedia, was initiated by unidentified state actors. Although most samples used in the attack are rather custom and do not show any similarity with previous attacks, two of them have rather interesting links:

KTAE analysis for two samples used in the SingHealth data breach

Mofang, a suspected Chinese-speaking threat actor, was described in more detail in 2016 by this FOX-IT research paper, written by Yonathan Klijnsma and his colleagues. Interestingly, the paper also mentioned Singapore as a suspected country where this actor is active. Although the similarity is extremely weak, 4% and 1% respectively, they can easily point the investigator in the right direction for more investigation.

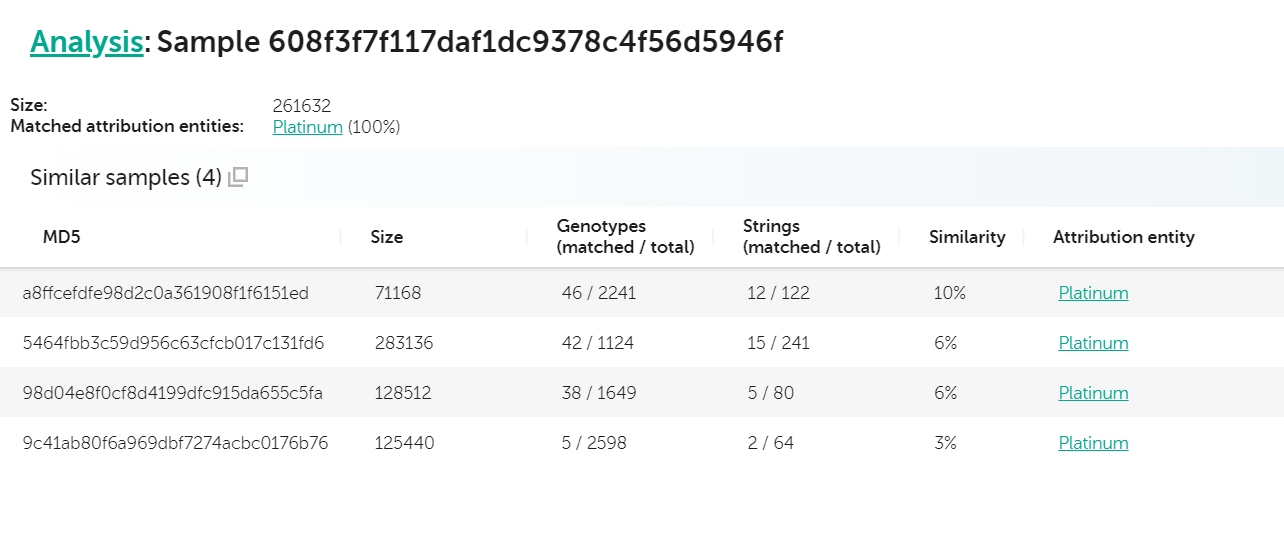

Another interesting case is the discovery and publication (“DEADLYKISS: HIT ONE TO RULE THEM ALL. TELSY DISCOVERED A PROBABLE STILL UNKNOWN AND UNTREATED APT MALWARE AIMED AT COMPROMISING INTERNET SERVICE PROVIDERS“) from our colleagues at Telsy of a new, previously unknown malware deemed “DeadlyKiss”. A quick check with KTAE on the artifact with sha256 c0d70c678fcf073e6b5ad0bce14d8904b56d73595a6dde764f95d043607e639b (md5: 608f3f7f117daf1dc9378c4f56d5946f) reveals a couple of interesting similarities with other Platinum APT samples, both in terms of code and unique strings.

Analysis for 608f3f7f117daf1dc9378c4f56d5946f

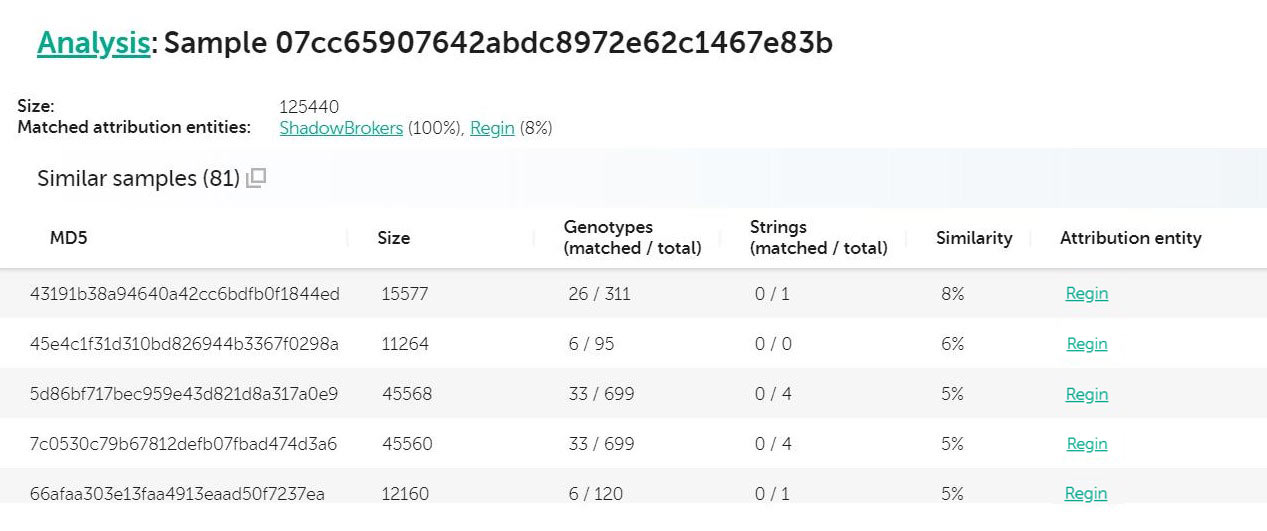

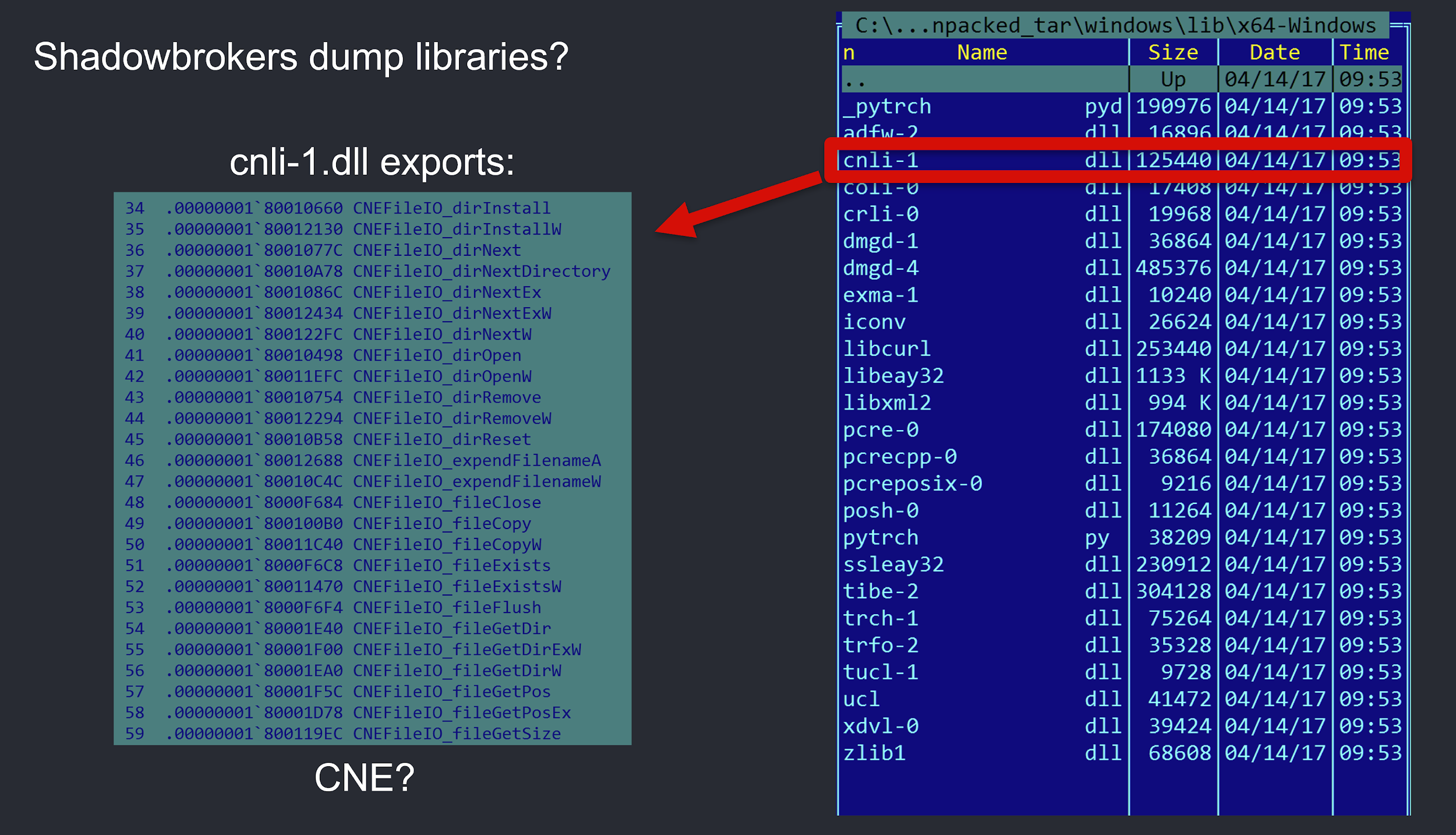

Another interesting case presented itself when we were analysing a set of files included in one of the Shadowbrokers dumps.

Analysis for 07cc65907642abdc8972e62c1467e83b

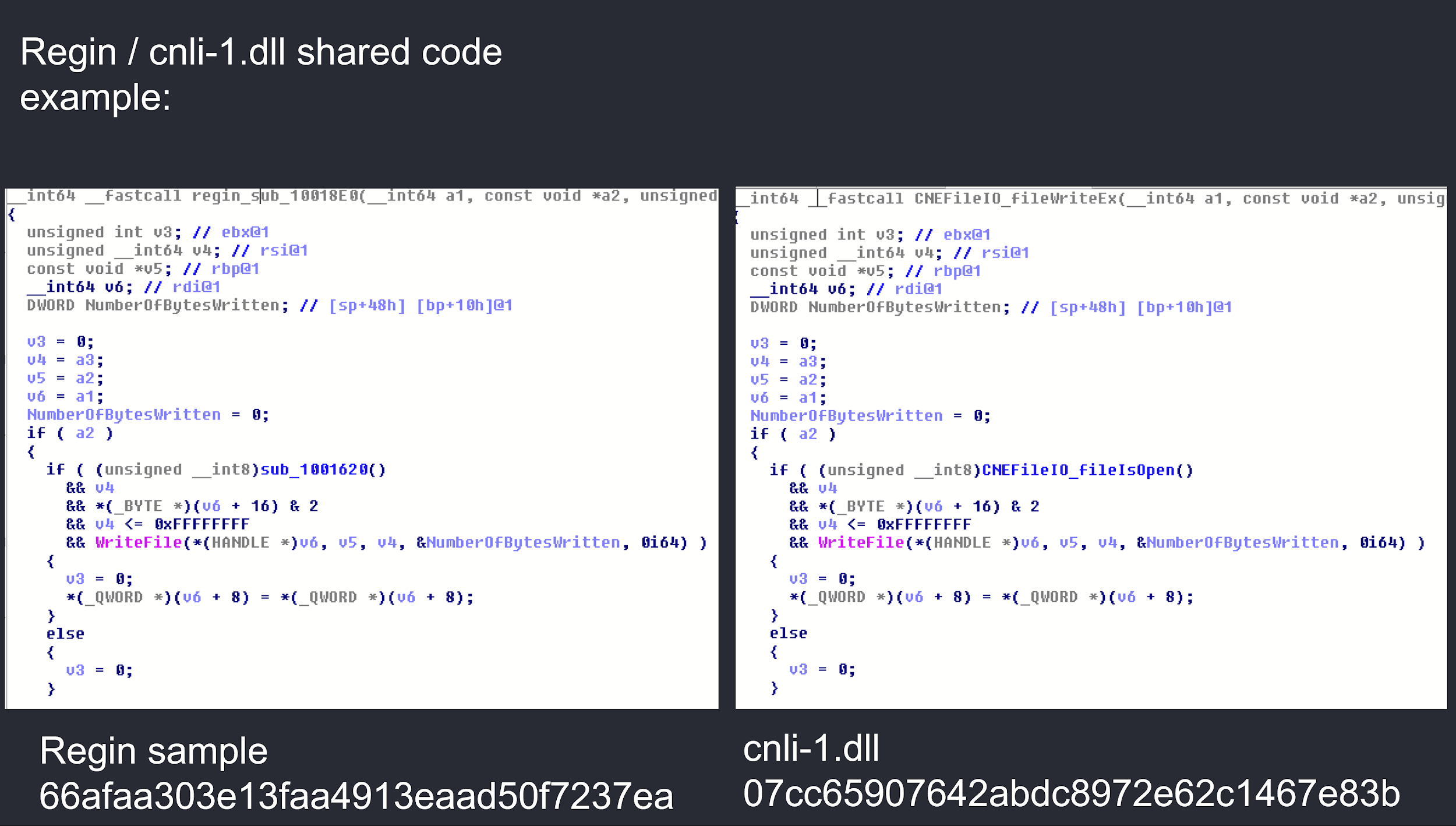

In the case above, “cnli-1.dll” (md5: 07cc65907642abdc8972e62c1467e83b) is flagged as being up to 8% similar to Regin. Looking into the file, we spot this as a DLL, with a number of custom looking exports:

Looking into these exports, for instance, fileWriteEx, shows the library has actually been created to act as a wrapper for popular IO functions, most likely for portability purposes, enabling the code to be compiled for different platforms:

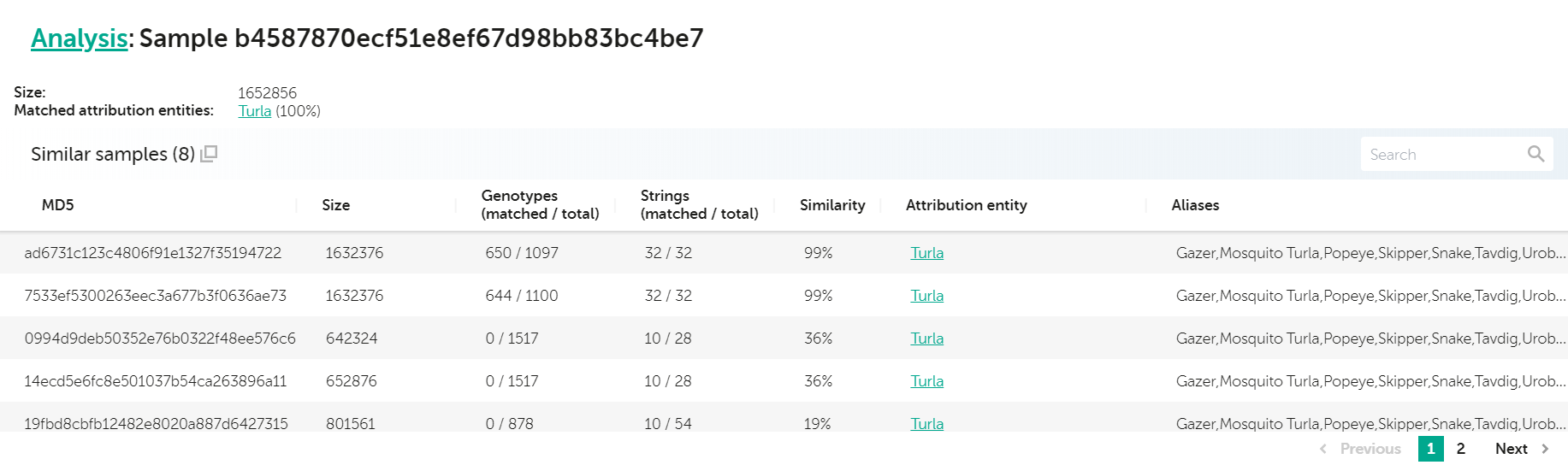

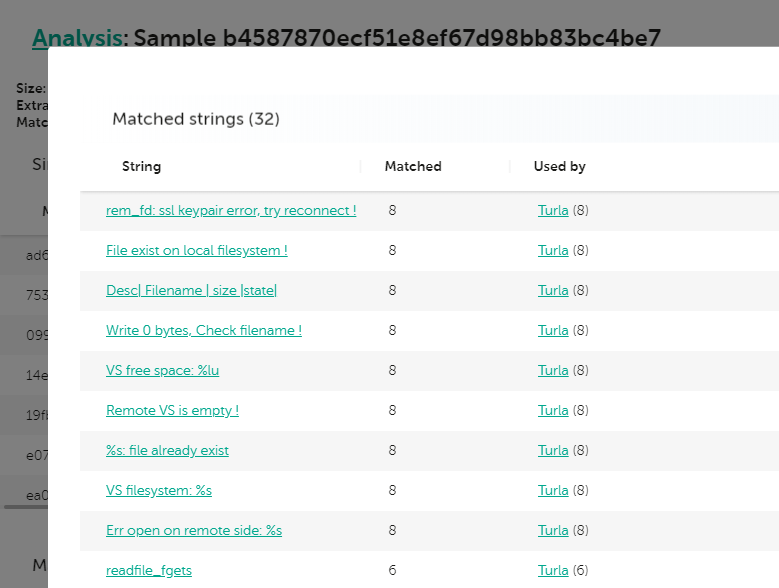

Speaking of multiplatform malware, recently, our colleagues from Leonardo published their awesome analysis of a new set of Turla samples, targeting Linux systems. Originally, we published about those in 2014, when we discovered Turla Penquin, which is one of this group’s backdoors for Linux. One of these samples (sha256: 67d9556c695ef6c51abf6fbab17acb3466e3149cf4d20cb64d6d34dc969b6502) was uploaded to VirusTotal in April 2020. A quick check in KTAE for this sample reveals the following:

Analysis for b4587870ecf51e8ef67d98bb83bc4be7 – Turla 64 bit Penquin sample

We can see a very high degree of similarity with two other samples (99% and 99% respectively) as well as other lower similarity hits to other known Turla Penquin samples. Looking at the strings they have in common, we immediately spot a few very good candidates for Yara rules—quite notably, some of them were already included in the Yara rules that Leonardo provided with their paper.

When code similarity fails

When looking at an exciting, brand new technology, sometimes it’s easy to overlook any drawbacks and limitations. However, it’s important to understand that code similarity technologies can only point in a certain direction, while it’s still the analyst’s duty to verify and confirm the leads. As one of my friends used to say, “the best malware similarity technology is still not a replacement for your brain” (apologies, dear friend, if the quote is not 100% exact, that was some time ago). This leads us to the case of OlympicDestroyer, a very interesting attack, originally described and named by Cisco Talos.

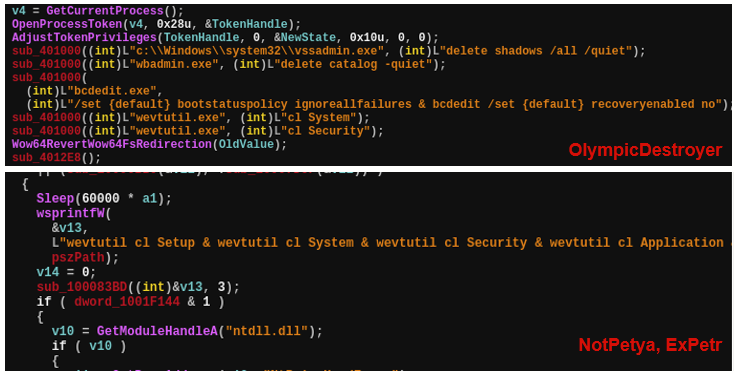

In their blog, the Cisco Talos researchers also pointed out that OlympicDestroyer used similar techniques to Badrabbit and NotPetya to reset the event log and delete backups. Although the intention and purpose of both implementations of the techniques are similar, there are many differences in the code semantics. It’s definitely not copy-pasted code, and because the command lines were publicly discussed on security blogs, these simple techniques became available to anyone who wants to use them.

In addition, Talos researchers noted that the evtchk.txt filename, which the malware used as a potential false-flag during its operation, was very similar to the filenames (evtdiag.exe, evtsys.exe and evtchk.bat) used by BlueNoroff/Lazarus in the Bangladesh SWIFT cyberheist in 2016.

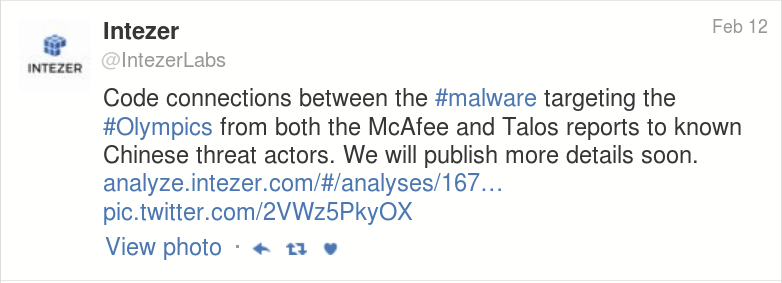

Soon after the Talos publication, the Israeli company IntezerLabs tweeted that they had found links to Chinese APT groups. As a side node, IntezerLabs have an exceptional code similarity technology themselves that you can check out by visiting their site at analyze.intezer.com.

IntezerLabs further released a blogpost with an analysis of features found using their in-house malware similarity technology.

A few days later, media outlets started publishing articles suggesting potential motives and activities by Russian APT groups: “Crowdstrike Intelligence said that in November and December of 2017 it had observed a credential harvesting operation operating in the international sporting sector. At the time it attributed this operation to Russian hacking group Fancy Bear”…

On the other hand, Crowdstrike’s own VP of Intelligence, Adam Meyers, in an interview with the media, said: “There is no evidence connecting Fancy Bear to the Olympic attack”.

Another company, Recorded Future, decided to not attribute this attack to any actor; however, they claimed that they found similarities to BlueNoroff/Lazarus LimaCharlie malware loaders that are widely believed to be North Korean actors.

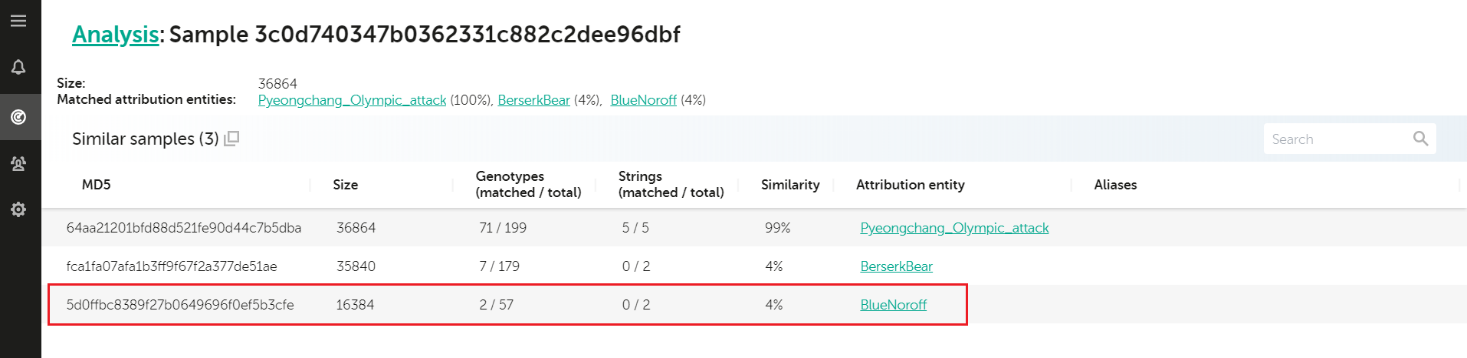

During this “attribution hell”, we also used KTAE to check the samples for any possible links to previous known campaigns. And amazingly, KTAE discovered a unique pattern that also linked Olympic Destroyer to Lazarus. A combination of certain code development environment features stored in executable files, known as a Rich header, may be used as a fingerprint identifying the malware authors and their projects in some cases. In the case of the Olympic Destroyer wiper sample analyzed by Kaspersky, this “fingerprint” produced a match with a previously known Lazarus malware sample. Here’s how today’s KTAE reports it:

Analysis for 3c0d740347b0362331c882c2dee96dbf

The 4% similarity shown above comes from the matches in the sample’s Rich header. Initially, we were surprised to find the link, even though it made sense; other companies also spotted the similarities and Lazarus was already known for many destructive attacks. Something seemed odd though. The possibility of North Korean involvement looked way off mark, especially since Kim Jong-un’s own sister attended the opening ceremony in Pyeongchang. According to our forensic findings, the attack was started immediately before the official opening ceremony on 9 February, 2018. As we dug deeper into this case, we concluded it was an elaborate false flag; further research allowed us to associate the attack with the Hades APT group (make sure you also read our analysis: “Olympic destroyer is here to trick the industry“).

This proves that even the best attribution or code similarity technology can be influenced by a sophisticated attacker, and the tools shouldn’t be relied upon blindly. Of course, in 9 out of 10 cases, the hints work very well. As actors become more and more skilled and attribution becomes a sensitive geopolitical topic, we might experience more false flags such as the ones found in the OlympicDestroyer.

If you liked this blog, then you can hear more about KTAE and using it to generate effective Yara rules during the upcoming “GReAT Ideas, powered by SAS” webinar, where, together with my colleague Kurt Baumgartner, we will be discussing practical threat hunting and how KTAE can boost your research. Make sure to register for GReAT Ideas, powered by SAS, by clicking here.

Register: https://www.brighttalk.com/webcast/15591/414427

Note: more information about the APTs discussed here, as well as KTAE, is available to customers of Kaspersky Intelligence Reporting. Contact: intelreports@kaspersky.com

Looking at Big Threats Using Code Similarity. Part 1

Chris

Hi Costin, excellent article. I just wanted to ask if I can get permission to use some of your graphs, with reference to this article, in my dissertation. I want to show what code-overlap looks like, and how malware families are identified.