In June 2018, we came across an unusual set of samples spreading throughout South and Southeast Asian countries targeting diplomatic, government and military entities. The campaign, which may have started as far back as 2012, featured a multi-stage approach and was dubbed EasternRoppels. The actor behind this campaign, believed to be related to the notorious PLATINUM APT group, used an elaborate, previously unseen steganographic technique to conceal communication.

As a first stage the operators used WMI subscriptions to run an initial PowerShell downloader which, in turn, downloaded another small PowerShell backdoor. We collected many of the initial WMI PowerShell scripts and noticed that they had different hardcoded command and control (C&C) IP addresses, different encryption keys, salt for encryption (also different for each initial loader) and different active hours (meaning the malware only worked during a certain period of time every day). The C&C addresses were located on free hosting services, and the attackers made heavy use of a large number of Dropbox accounts (for storing the payload and exfiltrated data). The purpose of the PowerShell backdoor was to perform initial fingerprinting of a system since it supported a very limited set of commands: download or upload a file and run a PowerShell script.

At the time, we were investigating another threat, which we believe to be the second stage of the same campaign. We were able to find a backdoor that was implemented as a DLL and worked as a WinSock NSP (Nameservice Provider) to survive a reboot. The backdoor shares several features with the PowerShell backdoor described above: it has hardcoded active hours, it uses free domains as C&C addresses, etc. The backdoor also has a few very interesting features of its own. For example, it can hide all communication with its C&C server by using text steganography.

After deeper analysis we realized that the two threats were related. Among other things, both attacks used the same domain to store exfiltrated data, and we discovered that some of the victims were infected by both types of malware at the same time. It’s worth mentioning that in the second stage, all executable files were protected with a runtime crypter and after unpacking them we found another, previously undiscovered, backdoor that is known to be related to PLATINUM.

Our paper only includes a description of the two previously undiscovered backdoors while the full report is available to customers of the Kaspersky Intelligence Reporting service (contact intelreports@kaspersky.com).

Steganography backdoor

The main binary backdoor is installed with a dedicated dropper. When the dropper is run, it decrypts files that are embedded into its “.arch” section:

Next, it creates directories for the backdoor to operate in and saves the malware-related files in these. It normally uses paths like those used by legitimate software.

Typically, the malware drops two files: the backdoor itself and its configuration file.

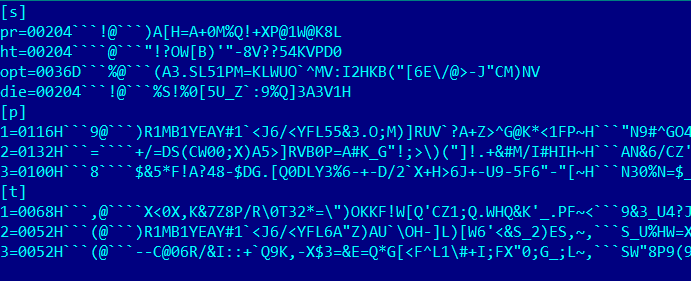

After this, the dropper runs the backdoor, installs it to enable a persistence mechanism and removes itself. The configuration file always has a .cfg or .dat extension and contains the following options, encrypted with AES-256 CBC and encoded:

- pr – stands for “Poll Retries” and specifies the interval in minutes after which the malware sends the C&C server a request for new commands to execute;

- ht – unused;

- sl – specifies the date and time when the malware starts running. When the date arrives, the malware clears this option.

- opt – stands for “Office Hours”. This specifies the hours and minutes during the day when the malware is active;

- die – stands for “Eradicate Days”. This specifies how many days the malware will work inside the victim’s computer;

- Section “p” lists malware C&C addresses;

- Section “t” lists legitimate URLs that will be used to ensure that an internet connection is available.

Persistence

The main backdoor is implemented as a dynamic link library (DLL) and exports a function with the name “NSPStartup”. After dropping it, the installer registers the backdoor as a winsock2 namespace provider with the help of the WSCInstallNameSpace API function and runs it by calling the WSCEnableNSProvider.

As a result of this installation, during initialization of the “svchost -k netsvcs” process upon system startup, the registered namespace provider will be loaded into the address space of the process and the function “NSPStartup” will be called.

C&C interaction

Once up and running, the backdoor compares the current time against the “Eradicate Days”, activation date and “Office Hours” values, and locates valid proxy credentials in “Credential Store” and “Protected Storage”.

When all the rules are fulfilled, the backdoor connects to the malware server and downloads an HTML page.

On the face of it, the HTML suggests that the C&C server is down:

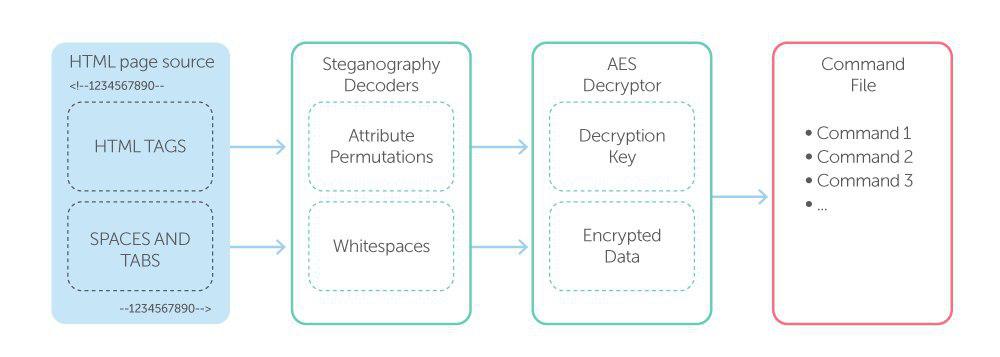

However, this is because of the steganography. The page contains embedded commands that are encrypted with an encryption key, also embedded into the page. The embedded data is encoded with two steganography techniques and placed inside the <--1234567890> tag (see below).

On line 31, the attributes “align”, “bgcolor”, “colspan” and “rowspan” are listed in alphabetical order, whereas on line 32, the same attributes are listed in a different order. The first steganography technique is based on the principle that HTML is indifferent to the order of tag attributes. We can encode a message by permuting the attributes. Line 31 in the example above contains four tags; the number of permutations in the four tags is 4! = 24, so the line encodes log2(24) = 4 bits of information. The backdoor decodes line by line and collects an encryption key for the data, which is placed right after the HTML tags in an encoded state too, but using a second steganography technique.

The image above shows that the data is encoded as groups of spaces delimited with tabs. Each group contains from zero to seven spaces and the number of spaces represents the next three bits of data. For example, the first group on line 944 contains six spaces, so it will be decoded as 610 = 1102.

Decryption of the decoded data using the decoded AES-256 CBC key is a logical continuation.

The result is a list of commands to execute, protected the same way as the backdoor configuration file:

Commands

The backdoor that we’ve discovered supports the uploading, downloading and execution of files, it can handle requests for a process list and directory list, upgrade and uninstall itself and modify its configuration file. Each command has its own parameters, e.g. the C&C server that it requests to download or upload files, or split a file while uploading.

Config manager

While investigating further, we found another tool that turned out to be a configuration manager – an executable whose purpose was to create configuration and command files for the backdoors. The utility can configure more than 150 options.

For example, below is the result of executing the showcfg command.

The second command it supports is updatecfg, whose job was to put values specified by the operator into the configuration file.

Also, the config manager supports Upload, Download, Execute, Search, UpdateConfig, AddKeyword, ChangeKeywordFile, ChangeKey, Upgrade and Uninstall commands. After executing any of these it creates a command file, protected the same way as the configuration file, and stores it in the “CommandDir” directory (the path is specified in the configuration, option 11). As described in the ‘Steganography backdoor’ section, this backdoor doesn’t handle command files and doesn’t support commands such as ChangeKeywordFile and ChangeKey, so we figured that there was another backdoor, which made a pair with the config manager we had found. Although it would appear such a utility should run on the attacker side, we found a victim infected with this and a corresponding backdoor located in the vicinity. We called it a P2P backdoor.

P2P backdoor

This backdoor shares many features with the previous one. For example, many of the commands have similar names, both backdoors’ configuration files have options with identical names and are protected the same way, and the paths to the backdoor files are similar to legitimate ones. However, there are significant differences, too. The new backdoor actively uses many more of the options from the config, supports more commands, is capable of interacting with other infected victims and connecting them into a network (see the “Commands” section for details), and works with the C&C server in a different way. In addition, this backdoor actively uses logging: we found a log file dating back to 2012 on one victim PC.

C&C interaction

This backdoor has the ability to sniff network traffic. After the backdoor is run, it starts a sniffer for each network interface, in order to detect a specially structured packet, which is sent to the victim’s ProbePort specified in the configuration. When the sniffer finds a packet like that, it interprets it as a request to establish a connection and sets TransferPort (specified in the configuration) to listening mode. The requester immediately connects to the victim’s TransferPort and both sides perform additional checks, exchanging their encryption keys. Then the connection requester sends commands to the victim, and the victim processes these interactively. This approach allows the backdoor to maintain listening mode without keeping any socket in listening mode – it only creates a listening socket when it knows that someone is trying to connect.

Commands

The backdoor supports the same commands as the steganography backdoor and implements an additional one. The backdoor leverages the Windows index service and can search files for keywords provided by the attacker. This search can be initiated by an attacker request or on a schedule – keywords for a scheduled search are stored in a dedicated file.

All commands are supplied to the backdoor through command files. The command files are protected the same way as the config (see below).

This consists of a command id (id), a command date (dt), a command name (t) and arguments (cmd).

The creators of the malware also provide the ability to combine infected victims into a P2P network. This can help the attacker, for example, when two infected victims share the same local network, but only one of them has access to the internet. In this case, the attacker can send a command file to the unreachable victim via the reachable one. The instruction for the reachable victim that the command is intended for the other host is placed directly inside the command file. When the attacker prepares the file, a list of infected hosts involved in transferring the file to the destination is included as the h1, h2, h3, etc. options. The order in which the command file will be transferred through the victims to the destination host is included as the p1, p2, etc. options. For example, if the p1 option equals ‘2->3->1’ and the p2 option equals to ‘2->3->4’ the command file will be delivered to the hosts with the indexes 1 and 4 through hosts 2 and then 3. Each host is described as follows: %Host IP%:%Host ProbePort%:%Host TransferPort%.

Conclusion

We have discovered a new attack by this group and noted that the actors are still working on improving their malicious utility and using new techniques for making the APT stealthier. A couple of years ago, we predicted that more and more APT and malware developers would use steganography, and here is proof: the actors used two interesting steganography techniques in this APT. One more interesting detail is that the actors decided to implement the utilities they need as one huge set – this reminds us of the framework-based architecture that is becoming more and more popular. Finally, based on the custom cryptor used by the actors, we have been able to attribute this attack to the notorious PLATINUM group, which means this group is still active.

IoCs

This list includes only IoCs related to the described modules of the attack. All IoCs are available to customers of the Kaspersky Intelligence Reporting service (contact intelreports@kaspersky.com)

Steganography backdoor installer:

- 26a83effbe14b63683f0c3e0a3f657a9

- 4b4c3b57416c03ca7f57ff7241797456

- 58b10ac25df04a318a19260110d43894

Obsolete steganography backdoor launcher:

- d95d939337d789046bbda2083f88a4a0

- b22499568d51759cf13bf8c05322dba2

Steganography backdoor:

- 5591704fd870919930e8ae1bd0447706

- 9179a84643bd6d1c1b8e6fe0d2330dab

- c7fda2be17735eeaeb6c56d30fc86215

- d1936dc97566625b2bfcab3103c048cb

- d1a5801abb9f0dc0a44f19b2208e2b9a

P2P backdoor:

- 0668df90c701cd75db2aa43a0481718d

- e764a1ff12e68badb6d54f16886a128f

Config manager:

- 8dfabe7db613bcfc6d9afef4941cd769

- 37c76973a55134925c733f4f50108555

Platinum is back

Markus Freitag

I do not understand why they put so much effort into the steganographic encryption of the remaining malicious code once the backdoor is installed and acting anyway.