How does a computer get infected if you’re just surfing the Internet? And how do cybercriminals make money from tricking users? This article aims to answer these questions.

The goal

In recent years, the threat of infection on the Internet has been increasing steadily. This is partly due, on the one hand, to the increasing number of people using the Internet, and an increasing number of online resources. It is also due, on the other hand, to cybercriminals’ desire to make as much money as possible. Today, attacks launched over the Internet are both the most numerous type of threat, as well as the most dangerous. Our monthly malware statistics confirm a huge number of online attacks, which are becoming ever more sophisticated. The most complex threats of late include ZeuS, Sinowal, and TDSS, all of which spread via the Internet. The plague of rogue antivirus solutions and blocker programs regularly encountered by Internet users tell a similar story. Operation Aurora, a targeted attack which received wide media attention was also conducted over the web (see: Operation Aurora). And this is just the tip of the iceberg.

In Internet attacks, the primary aim of cybercriminals is to download and install a malicious executable file onto a victim computer. Naturally, there are attacks such as cross-site scripting, also known as XSS, and cross-site forgery requests, or CSRF), which do not involve downloading or installing executable files on victim machines. However, being able to control an infected system from within opens up a whole world of opportunity; a successful attack provides cybercriminals with access to user data and system resources. And the cybercriminals will use this to make money from their victims in one way or another.

The attack

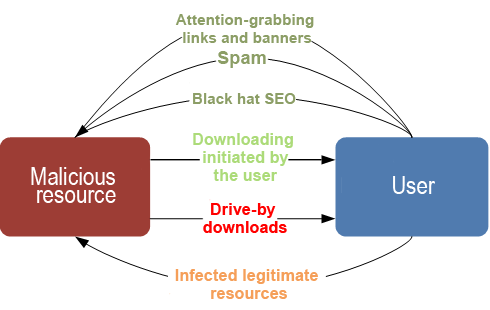

In general, an attack involves two steps: redirecting a user to a malicious resource, and downloading a malicious executable file onto his/ her computer.

Cybercriminals employ every possible channel in order to lure users to their malicious resources: email, instant messaging, social networks, search engines, advertising –malicious links can be found anywhere and everywhere. Sometimes, cybercriminals don’t have to do anything particular to attract users – they simply hack a legitimate website with a large number of visitors. Recently, cybercriminals have been resorting to this approach with increasing frequency.

Once a user has opened a “bad” resource, the only thing that remains is for malware to be downloaded and installed to his/ her computer. Cybercriminals have two choices: cause the user to download the program by him/ herself, or conduct a drive-by download. In the first case, social engineering methods are commonly used (see: engineering), where cybercriminals play on naivety and/or lack of experience. In the second case, cybercriminals exploit a vulnerability in software running on the victim’s computer.

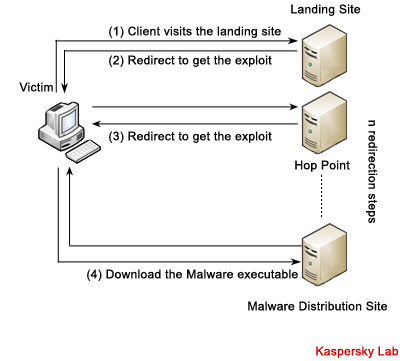

The picture below shows how attacks via the Internet download and install malicious files:

An Internet-based attack involving the download and installation of a malicious file

Let’s take a more detailed look at everyday Internet use and how a typical user may happen upon a “bad” web page, resulting in an infected computer.

Spam

Spam is one of the most tactics most commonly used by cybercriminals to lure users to malicious sites. And this type of spam exploits the possibilities of today’s Internet to the maximum. Even a few years ago, the word ‘spam’ was only associated only with advertising emails. Today, spam is spread via a number of different channels: instant messaging, social networking sites, blogs, forums, and even text messages.

Quite often, spam emails contain malicious executable files or links to malicious resources. Cybercriminals aggressively use social engineering in order to persuade users to click on links, and/or to download malicious files: they fill messages with links that appear to lead to hot news items or popular Internet resources and companies. In general, the cybercriminals play on human weaknesses: fear, curiosity, and excitement. This article does not examine social engineering techniques in detail, as a great number of examples of how malicious programs are spread using social engineering have already been published on our site.

Attention-grabbing links and banners

One method currently being used to attract users to malicious resources are banner ads and interesting-looking links. As a rule, these methods are most commonly found on illegal sites which offer unlicensed software or adult content.

Here’s an example of such an attack. When a user Googled “download crack for assassin’s creed 2” -this was a popular search in May 2010 – the results included the address of a web page that, when loaded, displayed a floating banner advertising Forex-Bazar.

A floating banner on a website offering unlicensed software

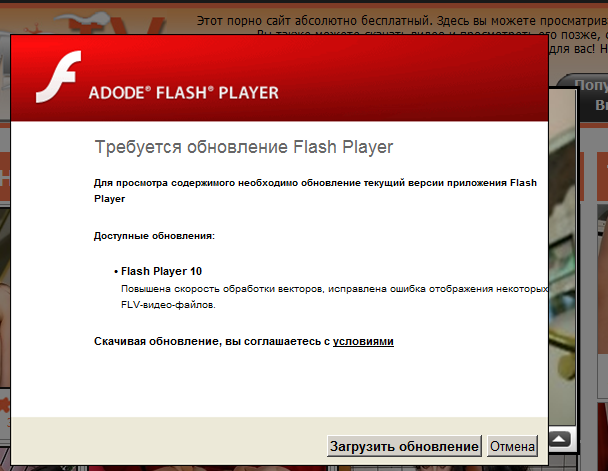

An attempt to close the banner resulted in a new browser window opening. This window displayed a website offering adult content videos. A click to ‘preview’ any of the videos, resulted in a message would being displayed saying an Adobe Flash Player update was needed in order to view the video.

Message appearing on a website afteran attempt to view an adult content video

Clicking on ‘download update’ and then ‘install update,’ results in, not an Adobe update being installed, but one of the most recent variants of Trojan-Ransom.Win32.XBlocker. This program then opens a window over all other windows, saying that a text message must be sent to a short number in order to get a key to “immediately uninstall the module,” and close the window.

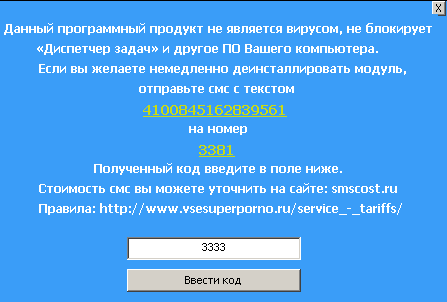

Window that appears after installing Trojan-Ransom.Win32.XBlocker

Black hat SEO

SEO (Search Engine Optimization) refers to methods used to improve a website’s position in search results returned by search engines in response to specific search terms. Today, search engines are a key resource when looking for information; the easier it is to find a website, the more demand there will be for services offered by the site.

There are numerous SEO methods – legitimate and prohibited by search engines. Kaspersky Lab is particularly interested in the use of prohibited SEO methods, also known as Blackhat SEO. These techniques are commonly used by cybercriminals to promote malicious resources.

Here is a general overview of how users come into contact with “optimized” resources, and how cybercriminals make their resources more visible.

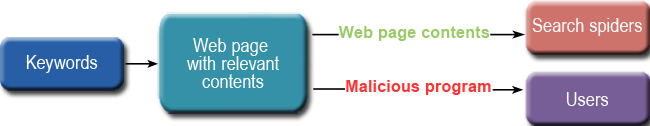

By using keywords, which can be entered either manually or automatically (for example, using Google Trends), cybercriminals create websites containing relevant content. Usually, this is done automatically: bots create search engines queries and steal content (fragments of text, for example) from pages that come top of the search results.

In order to ensure that a new website falls among the top search results, first and foremost, the creators have to force web crawlers, or spiders, to index it. The simplest way to initiate the indexing process is manually, by using, for example, the pages on Add your URL to Google, where users can enter their website into the search engine’s index. In order to push the site up toward the top of the results more quickly, a link to the site may be posted on resources that are already known to search engines, such as forums, blogs, or social networks. The link to the target page on these websites will make it appear more prominent during the indexing process. Furthermore, a site can be “optimized” with the help of botnets: infected computers conduct a search using specific keywords, and then select the cybercriminal website from the results.

A script is then put on the newly-created web page that, with the help of HTTP header processing, can be used to identify visitors. If the visitor is a web crawler, it will be “shown” a page with content associated with the chosen keywords. As a result, the page will be pushed up the list of search results returned. If a user is led to the site from a search engine, then s/he will be redirected to a malicious site.

Black hat SEO: creating and presenting data

Websites that are promoted using illegal or dubious methods are promptly removed by search engines from search results. This is why cybercriminals, as a rule, use automated processes to create and optimize such sites; this speeds up the process and multiplies the number of new malicious web resources.

Automatically created web pages can be placed anywhere: on cybercriminal resources, on legitimate resources that have been infected, or on free hosting services or blog platforms.

Close

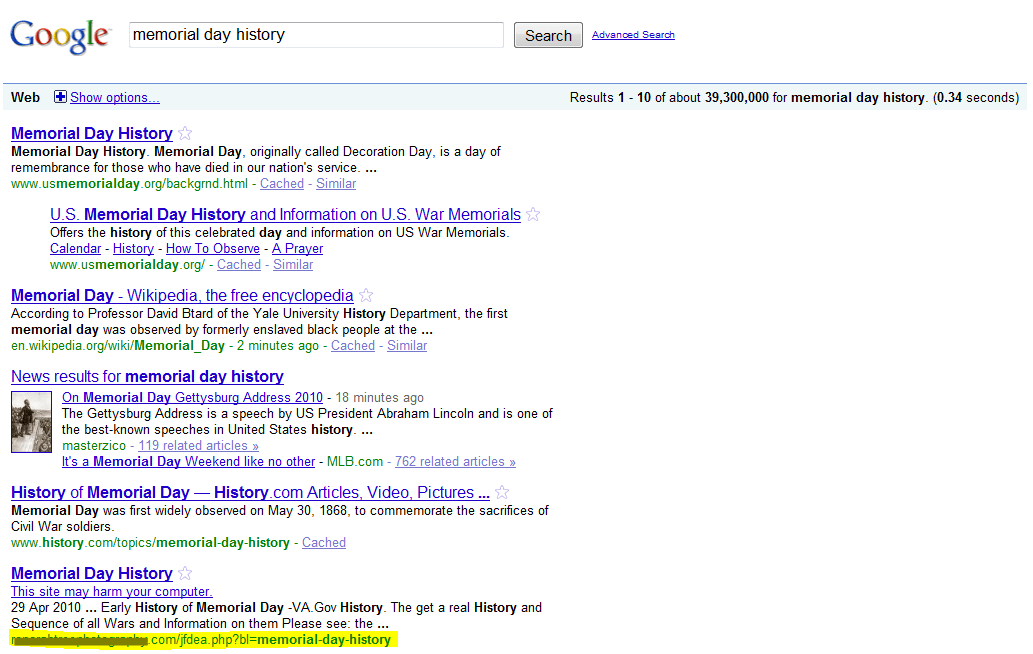

Here’s an example of black hat SEO. In May 2010, “memorial day history” was one of the most popular search terms. (This was connected to the US national holiday, Memorial Day, which is celebrated on the last Monday in May. The first page of results returned by Google includes a link that Google marked as suspicious.

Google results for “memorial day history.”

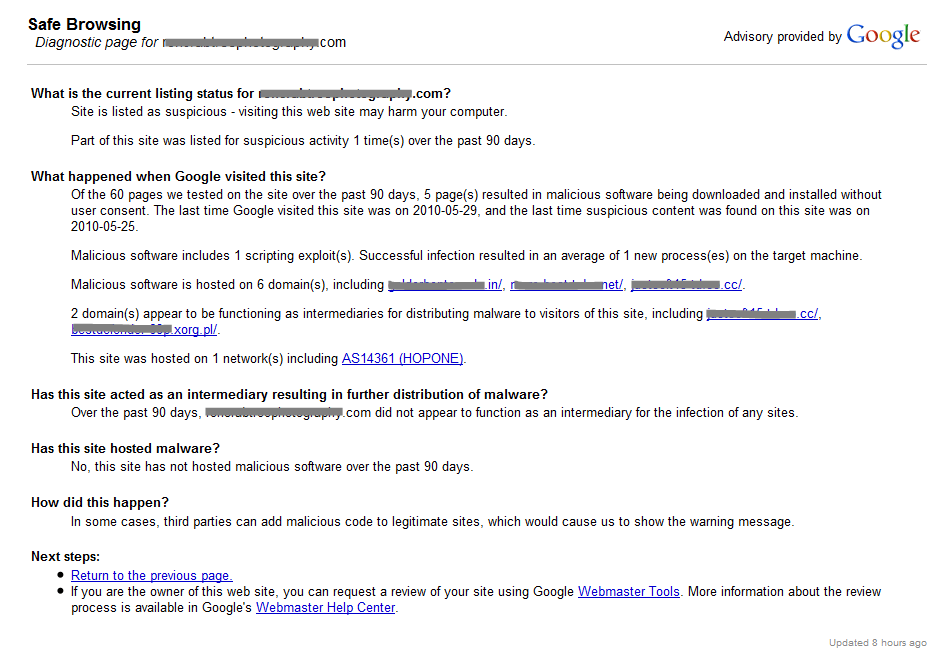

Google’s Safe Browsing statistics for this website reveal that numerous attack attempts have been made through this site.

Google’s Safe Browsing statistics for the website in question

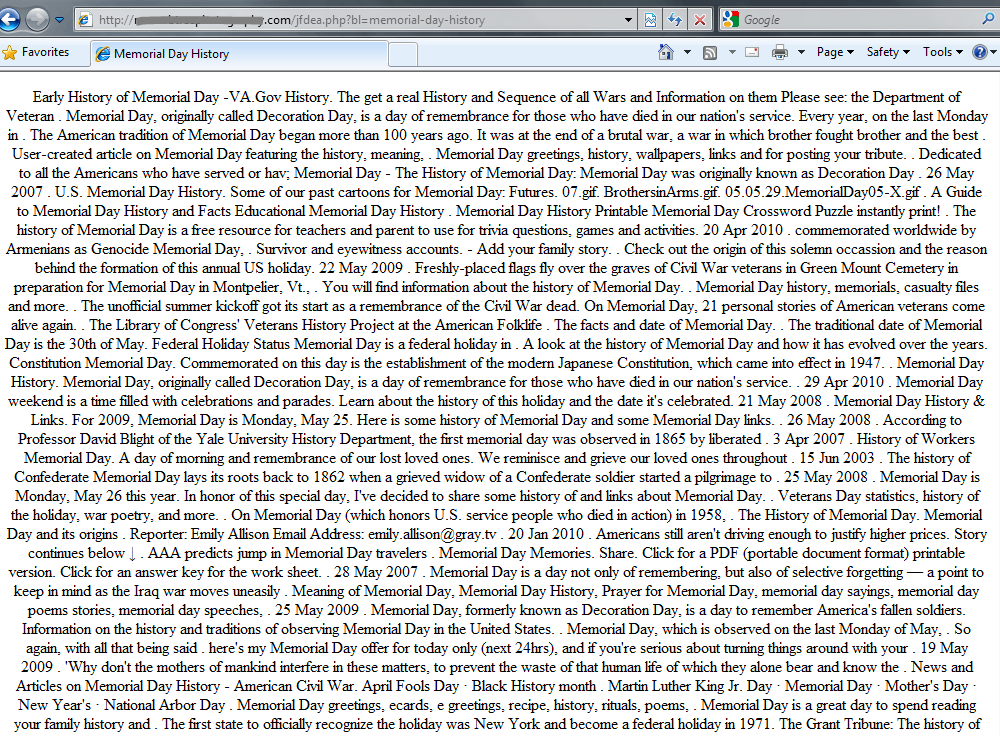

We attempted to visit this site by entering the address in the address bar in the browser, rather than following the link from the Google results. The site displayed a text document containing a large amount of text fragments relevant to “memorial day history” — just what search engine spiders are looking for!

Website content whichis returned when the URL is entered manually

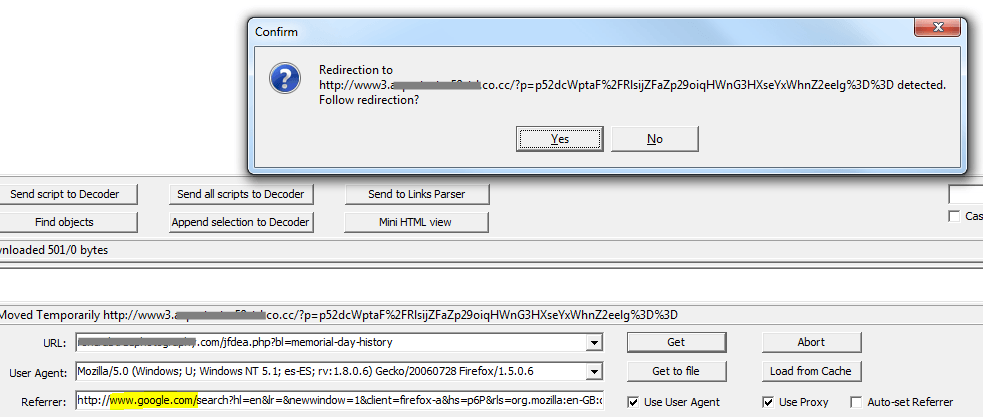

So what happens if a user visits the site by following the link in the Google results? The result is different: the server redirects the user to a different web resource.

Website contents when a user follows the link from Google’s list of search results

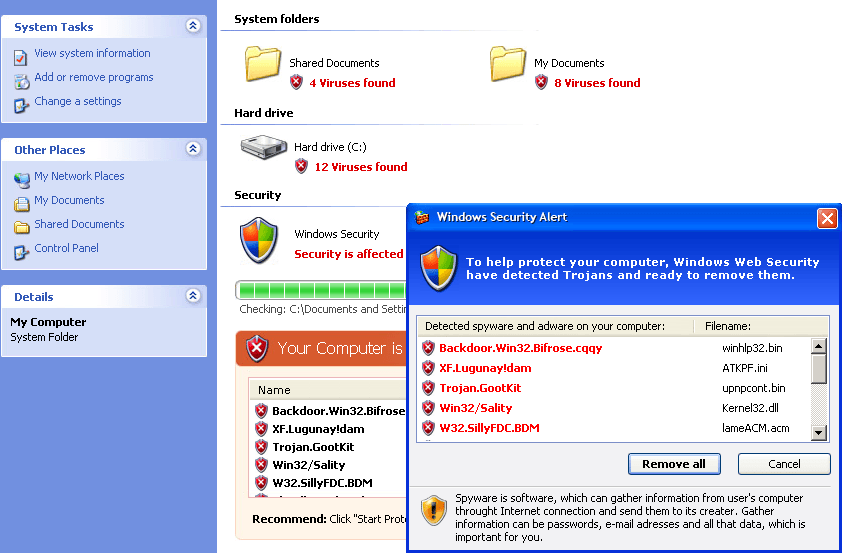

As a result of several similar redirects, a user will eventually arrives at a site displaying a message insisting that s/he should download an antivirus program (which is, naturally, a rogue solution).

Message saying the computer is infected, and that the user should install an “antivirus” program

It’s worth noting that just like the final page, the executable file also online hosted on a free service. As it is extremely easy for cybercriminals to register with free hosting services, all they then have to do to launch attacks is set up a redirect.

Close

The infection methods described above are only successful if the user agrees to download the program. More often than not, a user will download the file if he is inexperienced or not paying attention. Human weakness also plays a role in this process. For example, if a window pops up claiming that the computer is infected, the user may become concerned, and an inexperienced user may try to click on “remove all threats” as fast as possible. A window suggesting that the user download an update for Adobe Flash Player or a codec will not arouse suspicion, particularly as it looks legitimate; additionally, the user will often have clicked to download such standard, legitimate updates many times in the past.

Infected legitimate resources

One method in particular used to spread malicious programs has become increasingly prevalent: hidden drive-by downloads. In a drive-by attack, a computer is infected without the user noticing anything, and no user involvement is required. Most drive-by attacks are launched from infected legitimate resources.

Infected legitimate resources are perhaps one of the most serious and acute problems on the Internet today. Media outlets have published pieces with headlines such as “Mass hack plants malware on thousands of webpages“, “WordPress Security Issues Lead To Mass Hacking. Is Your BlogNext?” and “ Lenovo Support Website Infects Visitors with Trojan“. Every day, Kaspersky Lab identifies thousands of infected resources that download malicious code to a computer without user knowledge or consent. Drive-by downloads: the Internet under siege provides a more detailed overview of this type of attack.

As a rule, drive-by attacks do not entail persuading a user to visit a particular site; the user will come across the site as part of his regular routine. Such a site might be, for example, a legitimate (but infected) website that that the user visits daily in order to read the news or order a particular product.

A resource usually becomes infected in one of two ways: either via a vulnerability in the resource itself (for example, SQL injection), or by using previously-stolen confidential data to access a website. The most common method is to add a hidden tag called an iframe to the page’s source code. The iframe tag includes a link to a malicious resource and will automatically redirect a user when s/he visits an infected website.

The malicious resource hosts an exploit or a exploit pack that launches if the user has vulnerable software running on his/her computer. This leads to a malicious executable being downloaded and launched.

The illustration (from Google) below shows how such attacks work:

How the typical drive-by attack works

Exploit packs

Exploit packs are very commonly used in today’s drive-by attacks. An exploit pack is a set of programs that exploit vulnerabilities in legitimate software programs running on the victim machine. In other words, the exploits open a sort of back door via which malicious programs can infect the computer. Since attacks on the web take place through the browser, cybercriminals need to exploit vulnerabilities in the browser, in browser add-ons, or in third-party software which is used by the browser to process content. The main purpose of exploit packs is to download and launch executable malicious files without the user noticing.

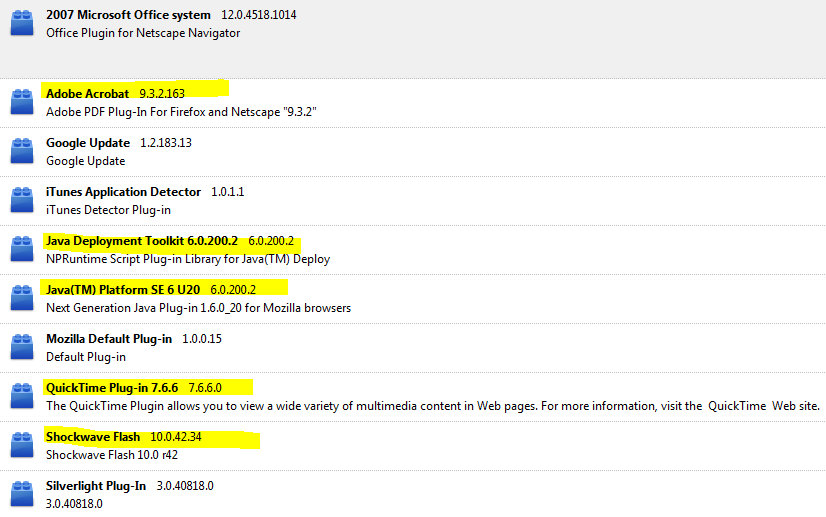

The screenshot below shows a typical set of add-ons for Firefox. The versions with vulnerabilities that have been exploited in previous attacks against users are highlighted. Furthermore, other vulnerabilities have been identified (and exploited) in Firefox itself.

Typical set of Firefox add-ons

Today, exploit packs represent the evolutionary peak of drive-by download attacks, and are regularly modified and updated. This is to ensure that they both include exploits for new vulnerabilities and are able to effectively counteract security measures.

Exploit packs have consolidated their niche on the cybercrime services market. At present, there are a great many exploit packs for sale on the black market; they differ in terms of price, the number of exploits included, the usability of the admin interface, and the level of customer service offered. In addition to the “off-the-shelf” exploit packs offered for sale, exploit packs can also be made to order, a service that is used by some cybercrime gangs.

The most common made to order exploit packs are those used in Gumblar and Pegel (script downloader) attacks.

What’s remarkable about the most recent version of Gumblar is the automated process used to infect websites and end user machines. Both exploits and executable files are used in the attacks, and these are placed on hacked legitimate resources. When a user visits a Gumblar-infected resource, he is redirected to another infected website, which will then infect his/ her machine.

In Gumblar attacks, known vulnerabilities in Internet Explorer, Adobe Acrobat/Reader, Adobe Flash Player, and Java are exploited.

Pegel also spreads via infected legitimate websites, but victim machines are infected via servers controlled by cybercriminals. This method makes it easier for cybercriminals to modify both the executable file and the exploit pack, enabling them to react quickly to new vulnerabilities. For example, one cybercriminal added an exploit to an exploit pack in order to target the vulnerability in theJava Deployment Toolkit. This was done almost as soon as the source code became available. The Twetti downloader is another Trojan that uses some interesting techniques. This malicious program creates a number of requests to the Twitter API, and uses the data it receives to generate a pseudo-random domain name. Users are then redirected to this domain name. Cybercriminals employ a similar algorithm to obtain a domain name, register it and then place malicious programs on the site to be downloaded to victim machines.

Close

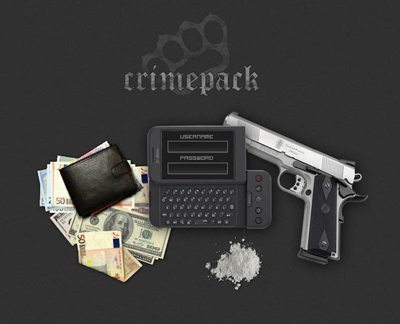

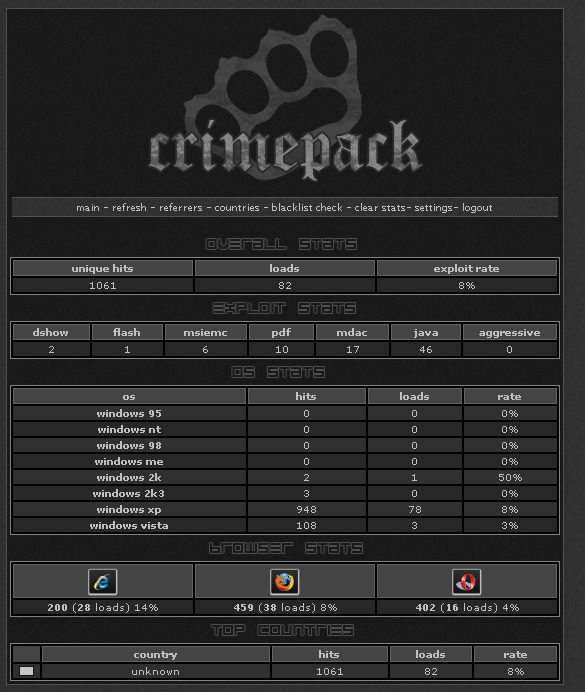

As an example, let’s take a look at one of the most common exploit packs currently on open sale: Crimepack Exploit System.

Crimepack features its own control panel with a high-quality user interface.

Crimepack admin panel: the authentication screen

The admin panel web interface can be used to modify the configuration of the exploit pack. It also provides statistics on the number of downloads, successful exploits, and the operating systems and browsers running on victim computers.

Crimepacks statistics page in the admin panel

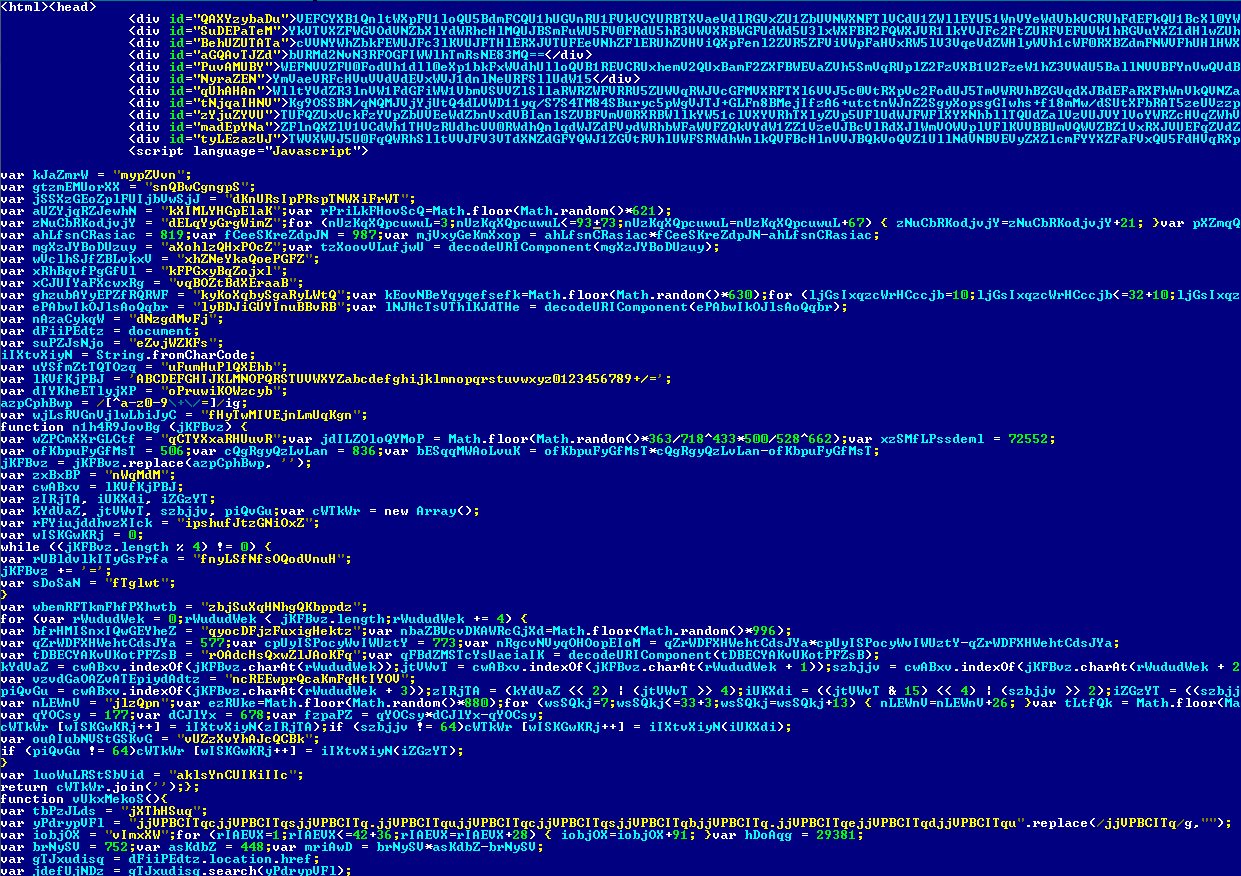

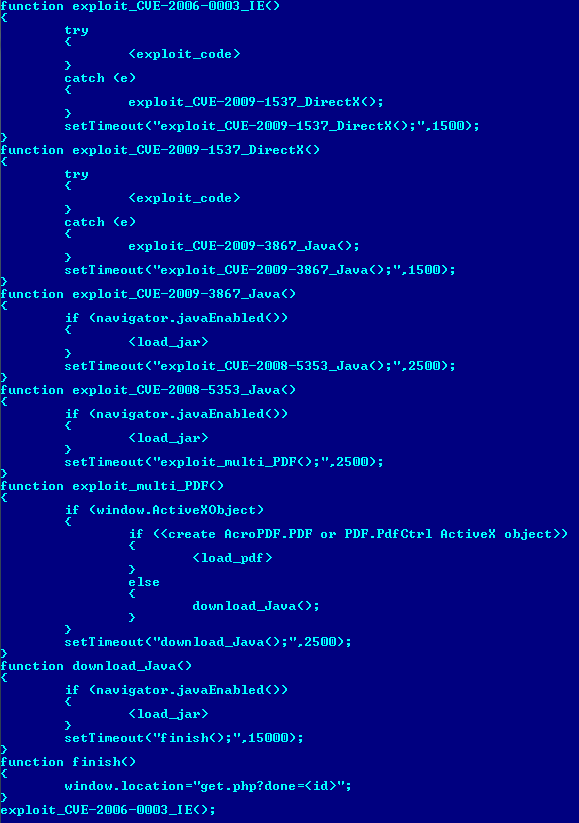

The exploit pack itself is an encrypted and obfuscated HTML page that includes JavaScript.

Crimepack exploits: source code

Analysis of the decrypted page makes it possible to trace Crimepack’s main functionality. The script within the page attempts, at set intervals, to exploit vulnerabilities in Internet Explorer, DirectX, Java, and Adobe Reader. During exploit attempts, a range of components are used, including malicious PDF and JAR files, which are loaded as the original script runs.

Crimepack exploits: main functionality

By early July 2010, Crimepack Exploit System had reached its third version, which contains 14 exploits targeting Microsoft, Adobe, Mozilla, and Opera products.

Close

Money

So who is making money from these attacks, and how?

Attacks using banner ads are lucrative for the owners of the web resource displaying the banner, as they are paid to display it. If XBlocker is downloaded and installed to a victim machine, then the cybercriminals using the malware benefit, but only if the user sends an SMS to the fee-based short number. Often, inexperienced users do end up taking the bait.

With regard to black hat SEO and attacks using sites which have been optimized in this way, it is those who have set up the distribution system, those who developed the software to automatically create fake websites and those who link the parties together who profit. If a user downloads and installs a rogue antivirus program, the cybercriminals who launched the attack will reap the benefits. Less experienced users will generally agree to install and pay for rogue antivirus solutions, which creates income for those who develop such programs.

Developers of exploit packs make money from drive-by attacks, as do those who use the packs. For example, the ZeuS Toolkit exploit pack is an efficient way to harvest confidential user data which can then be sold on the black market. As a result, regular Pegel attacks launched by malicious users have resulted in a botnet comprised of computers infected with Backdoor.Win32.Bredolab. The botnet can be used to download other malicious programs to victim machines.

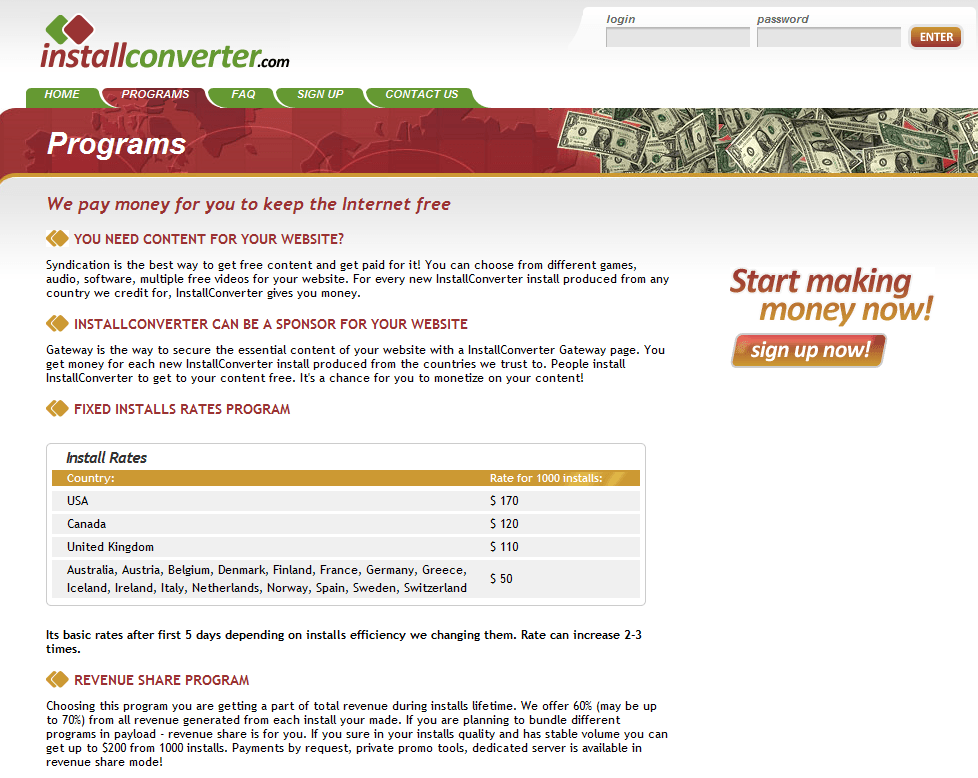

Does this all mean that cybercriminals make money when victims download malicious programs? Yes, of course! Affiliate networks (referred to in Russian as ‘partnerka’, i.e. partnership) and schemes are used to channel the profits made to the appropriate party or parties.

Affiliate networks

Affiliate networks have been around for some time now; they were initially used primarily to spread adware bundled with free applications. As a result, a ‘bonus’ of adware would be downloaded along with the application. Affiliate networks are now frequently used to spread malware.

The “black”, or illegal, pay-per-install (PPI) model includes the following main players (i.e., partners):

- The clients: cybercriminals who have a certain amount of money, and malware which they want to spread.

- Executors: these are the people who spread the program and earn money for doing so. Often, this affiliate won’t ask questions about what he is distributing; this can lead to becoming an unwitting accessory to cybercrime (however, ignorance does not constitute innocence).

- The PPI resource: this is an organization that connects clients with executors, and which earns commission on their transactions.

In addition to PPIs, which anyone can participate in, there are also numerous “closed” affiliate networks. These are only open to major players on the cybercrime scene, such as botnet owners, for example. Needless to say, huge sums must be circulating across such networks.

One question remains: where, or who, is this money coming from? The answer is, of course, from users. It is their personal funds, their confidential data, and/or the computing power of their machines at stake.

Close

InstallConverter is one of the more common PPIs out there today. As a rule, a PPI resource will pay for 1,000 unique downloads, with the amount per install depending on the location of the victim machine. The maximum payment is $170 which is paid for downloads to computers located in the U.S.

InstallConverter main page

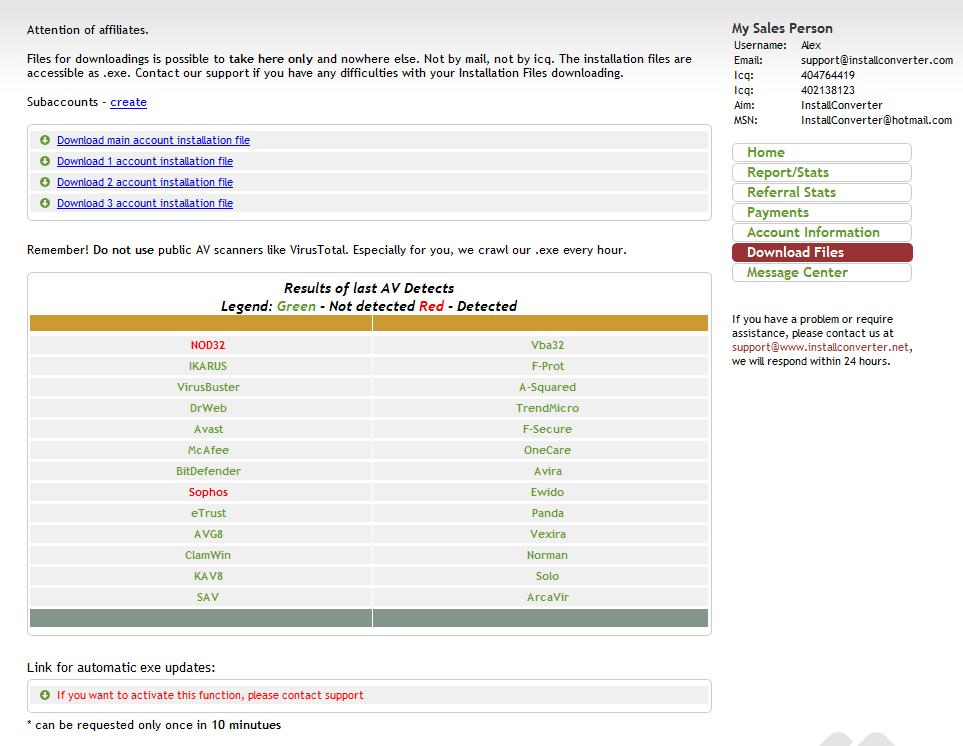

Once an affiliate has registered on the site and been approved, the owners will suggest that the affiliate download a “personal” executable file, which should then be distributed. “Personal” means that the affiliate’s assigned number is linked to the executable file, and this is used to track the partner’s progress. After getting the executable, the affiliate can distribute it by any means he wishes: via the web, via P2P sites (BitTorrent, eMule, DC++, or others), instant messaging clients, or even a botnet. The affiliate also has the ability to download a new executable via a link if the original file is detected by antivirus programs.

The ‘Download Files’ section, where affiliates can download executable files

However, the executable is not intended to be distributed directly; what should be spread is, for example, a small downloader program which will then download the malicious file. Alternatively, the malicious file will be “bundled” with a legitimate program and distributed to users disguised as a legitimate program. Another technique is to encrypt the executable using certain particular packing programs and distribute it in that form. In other words, the affiliate is limited only by his imagination and ability to put plans into practice.

It’s difficult to determine exactly which malicious programs have been distributed using InstallConverter since it first appeared, but over the past several months, it has been the exclusive method for installing TDSS, one of the most complex and dangerous backdoors currently in existence. TDSS is also able to download other malicious programs to infected computers. This means that owners of networks made up of TDSS-infected computers can act as affiliates and earn money from downloads.

Close

Conclusion

While the approaches and techniques described above do not cover every method used by cybercriminals, this article nevertheless addresses cover a large number of them.

The Internet is a dangerous place these days — all you have to do is click on a link provided in search results, or visit a favorite webpage that has recently been infected — and before you know it, your computer is part of a botnet. Cybercriminals’ primary objective is to ‘relieve’ users of their money and their confidential data; the data can then be monetized for further profit. This is why cybercriminals use everything they have in their arsenal in order to deploy malicious programs to user computers.

In order to protect yourself, you need to update your software regularly, especially software that works in tandem with your web browser. A security solution which is kept up-to-date also plays an important role. And, most importantly, you should always be cautious regarding information which is spread via the Internet.

The Perils of the Internet