Why Economic Incentive May Lead to the Failure of Bitcoin

Let us discuss what defines the profitability of bitcoin mining, what principles for mining speed adaptation were initially embedded into it, and why these principles can lead to the failure of the cryptocurrency in the long run.

We assume that the reader has an idea of basic Bitcoin mechanics such as blockchains, mining, mining pools, and block rewards.

Note: In this article, we investigate a theoretical possibility of how the described scenario may evolve by considering the algorithms embedded in Bitcoin. Our goal was not to make a deep analysis of the structure of miner expenditures, electricity prices in different areas of the world, bank interest rates, or payback periods for equipment.

A 51% attack

The Bitcoin community is well aware of “51% attack”. If a miner controls more than a half of all of the mining hashrate, then he or she is capable of doing the following:

- Pay with his or her bitcoins for a commodity or service or exchange them for traditional money.

- Begin generating blocks that do not include the mentioned transaction, but not show the generated blocks to other miners.

- Wait until the commodity has been delivered.

- Publish the generated chain of blocks.

At the same time, the following happens:

- All of the other miners will have to accept the fraudster’s blockchain version as the only one that is genuine because it is longer and the miner has a mining hashrate that is more powerful than that of all of the participants put together.

- The fraudster receives the commodity and keeps his/her bitcoins, as he or she did not spend them in his or her version of history.

- The fraudster receives the reward for all of the generated blocks, not for one half of the blocks, which is what they would generate if they were playing fair and adding blocks to a common chain.

- The fraudster during the Attack will most likely buy coins of another cryptocurrency using bitcoins, as it is fast, quite safe, and irreversible.

The community concurs that such an attack if it were possible, would raise questions about the further existence of Bitcoin.

It is important to note that a successful attack does not necessarily entail a 51% or higher hashrate. There is some possibility that it can be carried out with a smaller hashrate share. For example, owning 30% of hashrate gives the attacker about an 18% chance of generating a chain of five blocks in a row, which would be longer than the shared one. In that case, the attacker gains all of the same privileges as in a 51% attack. In case of failure, the attacker can just try again. The majority of services that receive bitcoin payments require only five “confirmations”, which means that such a generated chain will be enough.

Adaptation of mining difficulty

After generation of a pack of 2016 blocks, the Bitcoin network adapts the difficulty of mining. The standard of difficulty is when the mining of one block takes around 10 minutes. Therefore, mining 2016 blocks will take two weeks. If the generation process took, for instance, only one week, then the difficulty will be increased twofold after the next reassessment (so that it would take two weeks to generate the next 2016 blocks at the same network hashrate).

It’s worth noting that the Bitcoin network uses software to prohibit changing the difficulty of mining more than four times per one reassessment.

There are direct consequences stemming from these rules. If mining hashrates are added or removed during a period of 2016 blocks, then the following occurs:

- This does not affect the reward received by the remaining miners in any way. The reward is determined by the hashrate of a miner but not their share in the common hashrate. For example, after one half of the hashrates have been deactivated, the remaining miners will mine twice as many blocks; but this will require double the time. Income will be retained.

- This directly affects the output rate. If 99% miners stop mining, then the next difficulty reassessment will occur in 4 years. Creation of one block will take about 16 hours.

The authors of Bitcoin assumed that the described algorithm would smoothly adjust network power by pushing out less power-efficient equipment and restoring the reasonable marginality of the remaining equipment. However, what this rare difficulty reassessment does is open the door to another strategy for miners: they may trick the algorithm by artificially lowering network performance. After all, when a rig is abruptly powered down, the revenue generated for the day stays at the same level; and when a rig is suddenly powered up, costs are lowered.

Mining fees and the free will of miners

In addition to receiving a reward for a block (of an emitted currency), miners also collect fees for transactions that are included in the block. As of today, the fees currently sit at approximately 10% of the block reward. We won’t dwell on this for too long, but, nevertheless, according to our estimations, it turns out that the existence of fees makes the miner strategy that we are researching here even more appealing.

Another aspect is that mining pools frequently do not directly control the mining rigs that are part of those pools. Each participant and rig owner is free to choose the pool that they will work in. The decision to move from one pool to another is usually based on economic grounds.

However, the person in charge of the pool determines the policy regarding powering up and powering down the rigs and switching the rigs to mine an alternative currency (Bitcoin Cash). In other words, we think that the described behavioral strategy should be adopted and implemented by only about 20 participants who are pool owners: the rig owners do not matter in the least here even though they possess their own “free will”.

Let’s suppose that the total hashrate of all of the miners has been stabilized and review one of the strategies for increasing marginality.

An example of miner behavior during a stable Bitcoin network hashrate

For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume that you control one half of all of the hashrates of the Bitcoin network. You can keep the rig turned on all the time and receive the reward for about 1008 blocks (50%).

You could also do the following:

- Wait until the next period of 2016 blocks.

- Turn off your mining rigs.

- Wait until the remaining miners get 2016 blocks within 4 weeks.

- After that, the Bitcoin network will halve the mining difficulty for the next period.

- You can turn on your rigs, and the entire network will mine 2016 blocks within one week.

- You will receive a reward for the same 1008 blocks (approximately) within just a week.

Please note the first scenario assumes that five weeks of regular operation will yield a reward for 5/2 × 1008 = 2520 blocks, but you would have to pay for electricity for the entire time period. The second scenario assumes that the same five weeks will yield a reward for 1008 blocks, but you would have to pay the electricity costs for only one week.

Let’s suppose that the electricity price comprises only about 90% of the reward. It is easy to calculate that the first scenario assumes that a five-week profit is equivalent to a reward for 2520 ? 0.1 = 252 blocks, while the second scenario yields a reward for “reward ? costs” = 1008 ? 0.9 ? 1008/2 = 554.4. This means that the proposed strategy turns out to be twice as lucrative.

Economically profitable miner behavior with different parameters

Let’s assume the following.

- A smart miner controls a share x, of the total network hashrate.

- The bitcoin reward for all of the 2016 blocks is A.

- The electricity and maintenance costs for two weeks of network rig operation equals C. We assume that the rent of premises and downtime costs are insignificant. To simplify the calculation, we deliberately disregard the depreciation of the rig.

Thus, the following happens.

- A miner’s reward is Ax ? Cx for the time period of two weeks of regular operation.

- If a smart miner turns off his mining rig, the network will produce 2016 blocks within the period that will take

as much time.

as much time.

For example, if x = 1/3, then it will take one and a half as much time to finish the task. - After the end of the period when the network adapts the difficulty, and the smart miner turns on the rig, the network will complete the task (1 − x) times faster than the planned two weeks.

For example, if x = 1/3, then it will require 2/3rd of the regular time after the rig has been turned on, which is approximately 10 days. - The total duration of the two periods will be (

) × (2 weeks);

) × (2 weeks); - Thus, in regular conditions (without downtime), working during these two periods lets miners earn

Pregular operation = ( ) × (A − C) = (

) × (A − C) = ( ) × (A − C)

) × (A − C)

This means that all of the miners earn a little more than double the net profit for the prolonged conventional period. - A smart miner who operates with downtime will earn nothing for the first period, but the second period (the shorter one) will yield

Psmart = Ax − Cx(1 − x) = Ax − Cx + Cx2

This means that the smart miner gains a single regular net profit and additionally saves up the share of x of the costs. - During the slow period, all of the non-disconnected miners will earn Pslow period = A ? C,

and for the fast period: Pfast period = A ? C (1 ? x), as the reward is the same, but they work faster.

It is easy to see the following:

- If the expenditures of miners are precisely equal to their rewards (the miners work with a margin of zero), then the clever approach would let them gain a net profit of Ax2.

- If miners pay no electricity costs (a margin of 100%), then they will earn more than double the amount of income within the period of regular operation and a only one regular amount of income when working with downtime.

- Let’s find out how much of the rig power x should be turned off in order to maximize the revenue for all miners with a margin of M = (A − C)/A:

maxx(Pslow period + Pfast period − Pregular operation) =

maxx( − (

− ( )

)

maxx( − (

− ( )M)

)M)

maxx( ) =

) =

maxx( )

)

This equation reaches its maximum at x = 1 −  . For example, smart miners should temporarily disable 80% of their rig power when M = 4%.

. For example, smart miners should temporarily disable 80% of their rig power when M = 4%.

Why miners are not using the described strategy right now

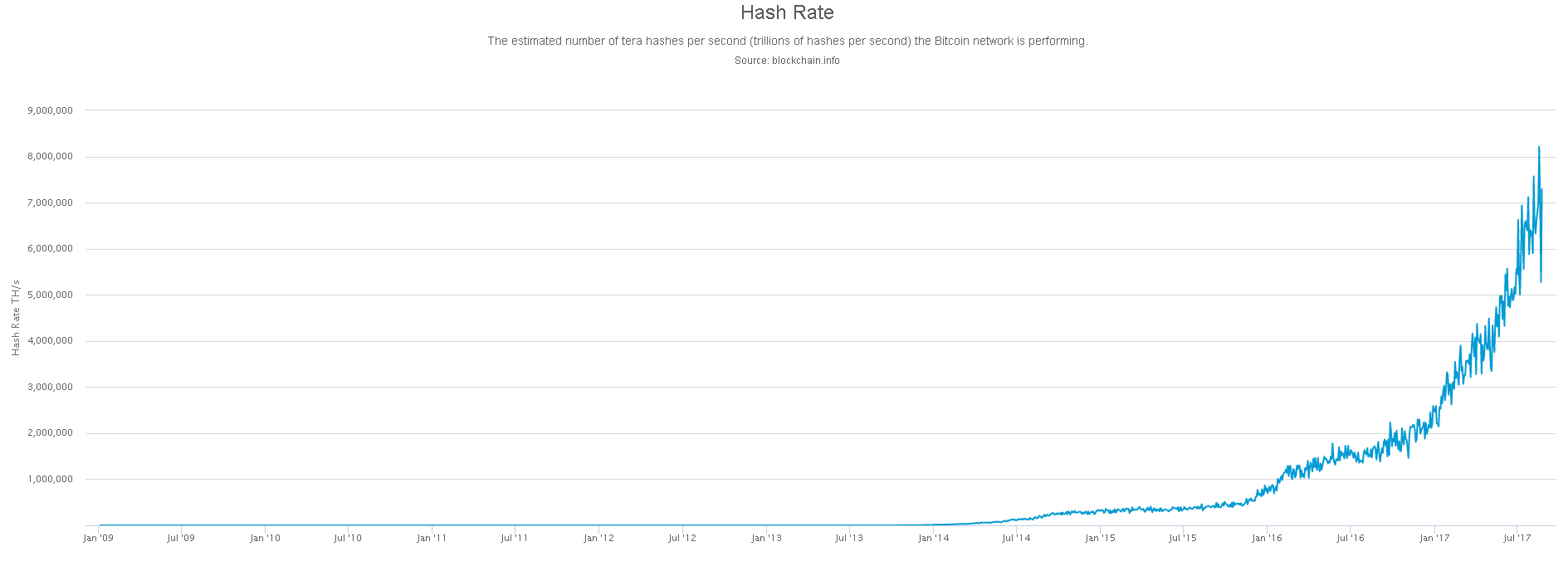

The increase of hashrate on the Bitcoin network. The hashrate of the network has grown by 4 times in a year (Source)

The increase in difficulty on the Bitcoin network for the entire time period. Starting January 2016, the difficulty has been increased by 8 times, just like the value of bitcoin (Source)

The described strategy makes sense only under the condition that the overall network difficulty does not increase over time. Otherwise, turning off rigs will not lead to a decrease in difficulty, which makes this economically unviable.

Up until now, mining hashrates have been increasing at a fast tempo; this is a consequence of the growth of the bitcoin exchange rate. The income of miners is estimated in bitcoins, but they pay for costs in traditional currency.

The growth rate of bitcoin value (Source)

Nevertheless, it would be reasonable to suppose that if the bitcoin does not endlessly grow in price, then at some time introducing new mining hashrates would not be economically viable and electricity costs would sooner or later be practically equal to the reward.

The dangers of turning off mining hashrates

When new mining hashrates are no longer introduced, miners will may resort to the above-mentioned strategy.

An estimate of hashrate distribution among the largest mining pools (Source)

If mining pools maximize their own profit, then 75% of hashrates are expected to be turned off at a margin of 6.25%. There is no sense in switching off more rigs, as the network will not reduce its difficulty by more than 4 times.

After that, in order to carry out a 51% attack, a fraudster must either control more than one half of the remaining hashrate (which can be easily done with the current distribution of hashrates) or suddenly turn on more rigs than were working before (which is currently unfeasible, considering the share of the largest pool).

Now, the question arises as to whether attacking the network is profitable for a person who has invested considerable amounts into increasing mining hashrates. Well, the answer is “yes, it is profitable”. In case of low mining marginality, the price of the existing mining rig is decreased too. In other words, if mining brings no revenue, then playing honestly will no longer be viable. Aside from that, the attacking party may remain anonymous and, among other things, speculate for a fall of the bitcoin price.

A Bitcoin Cash attack

We are intentionally not considering a situation where the price of electricity quickly and significantly goes up or where the price of bitcoins falls quickly and by a significant amount (which is much more likely to happen). If that happens, then the miners’ strategy is quite obvious. During drastic price variations, all miners will turn off their rigs. Perchance, only those who take advantage of free electricity will stay afloat. In that case, network operation will simply stop: finishing the “two weeks” will require a lifetime, while the inability to carry out a transaction will lower the bitcoin’s price even more.

Our colleague from BitcoinMagazine analyzed the situation with the Bitcoin Cash currency just the other day. This currency appeared after Bitcoin network split on August 1, 2017. The new currency has a feature called Emergency Difficulty Adjustment (EDA). The EDA allows for adaptation of the difficulty on the Bitcoin Cash network even more often. This means that the difficulty is lowered by 20% if fewer than 6 blocks were mined in the span of 12 hours. The author comes to a conclusion similar to ours, but what’s more important is that he mentions that he has already been observing manipulations by smart miners. He fears destabilization of the Bitcoin Cash network and is counting on a prompt solution from developers.

Conclusion

We have analyzed one of the economically viable strategies of honest miners after the hashrate of the Bitcoin network stops growing. We have also calculated some of the key values of this strategy and inferred that using it is profitable for each individual participant but also considerably increases the risk of a 51% attack and a potential crash of the Bitcoin network as a whole.

If all of the miners were capable of coming to a solid agreement, they would go even further by turning off all but one of the rigs. This would be optimal in respect to revenue but fatal from the point of view of network security.

How should miners act in order to guarantee security? Here we can see a couple of analogies. The first one is an overproduction crisis. When this happens, manufacturers come to an agreement to publicly eliminate some of their products (at least, this was how it happened in the Middle Ages). The second one is nuclear disarmament, where countries that own large arsenals of nuclear weapons arrange for their proportional reduction.

Ideally, all miners should agree on turning off some of their rigs and, above all, on the controlled destruction of their rigs. It would be important not only to destroy rigs systematically but to control their production in a strict manner as well.

We do not have to rely on such a “peaceful” resolution. The recent split of the Bitcoin chain into two chains and the formation of Bitcoin Cash reveal that miners are not always able or have the desire to solve common problems together. It is possible that the ability to cooperate will become a decisive factor in the future.

Only time will tell how our theoretical research corresponds with actual practice.

Satoshi Bomb

Dragan

“Our goal was not to make a deep analysis of the structure of miner expenditures, electricity prices in different areas of the world, bank interest rates, or payback periods for equipment.”

Whole genius of Satoshi’s invention is the “incentive balance” and for some reason that small fact is discarded.

“We have analyzed one of the economically viable strategies…”

Economy without prices? What kind of economy is that?

Advice:

Attack bitcoin more

Buy scam-coins

Bitcoin price will go up because of failed attacks and scams

Honey Badger doesn’t care. Buy bitcoin.