When we use popular apps with good ratings from official app stores we assume they are safe. This is partially true – usually these apps have been developed with security in mind and have been reviewed by the app store’s security team. However, we found that because of third-party SDKs many popular apps are exposing user data to the internet, with advertising SDKs usually to blame. They collect user data so they can show relevant ads, but often fail to protect that data when sending it to their servers.

During our research into dating app security, we found that some analyzed apps were transmitting unencrypted user data through HTTP. It was unexpected behavior because these apps were using HTTPS to communicate with their servers. But among the HTTPS requests there were unencrypted HTTP requests to third-party servers. These apps are pretty popular, so we decided to take a closer look at these requests.

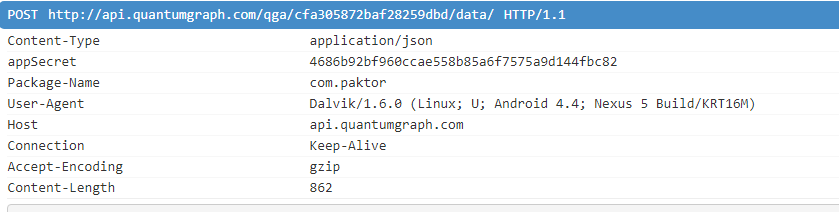

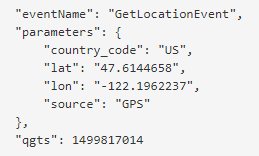

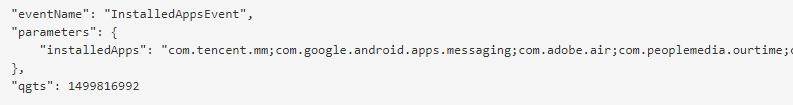

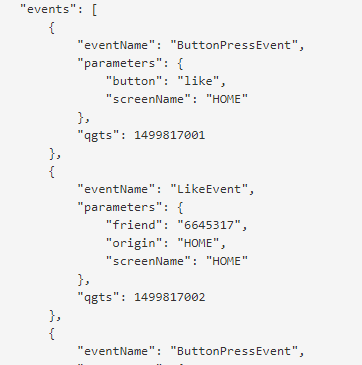

One of the apps was making POST requests to the api.quantumgraph[.]com server. By doing so it was sending an unencrypted JSON file to a server that is not related to the app developers. In this JSON file we found lots of user data, including device information, date of birth, user name and GPS coordinates. Furthermore, this JSON contained detailed information about app usage that included information about profiles liked by the user. All this data was sent unencrypted to the third-party server and the sheer volume makes it really scary. This is due to the use of a qgraph analytics module.

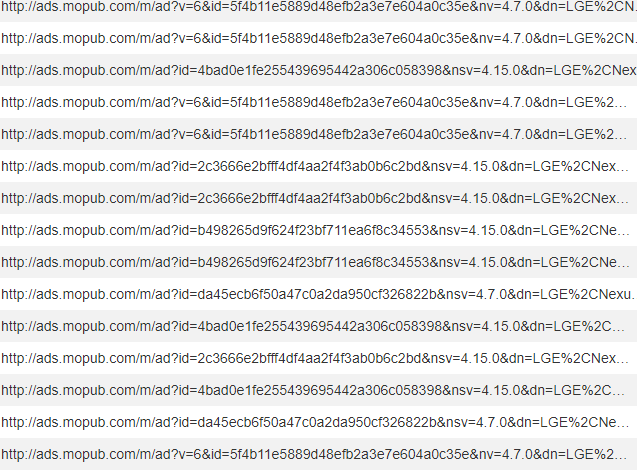

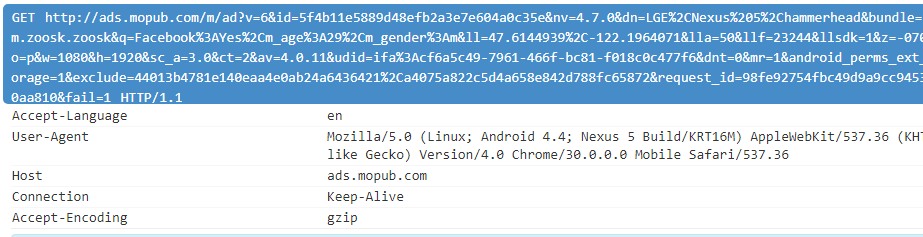

Two other dating apps from our research were basically doing the same. They were using HTTPS to communicate with their servers, but at the same time there were HTTP requests with unencrypted user data being sent to a third-party server. This time it was another server belonging not to an analytics company but to an advertising network used by both dating apps. Another difference was GET HTTP requests with user data being used as parameters in a URL. But in general these apps were doing the same thing – transmitting unencrypted user data to third-party servers.

At this point it already looked bad, so I decided to check my own device, collecting network activity for one hour. It turned out to be enough to identify unencrypted requests with my own data. And again the cause of these requests was a third-party SDK used by a popular app. It was transmitting my location, device information and token for push messages.

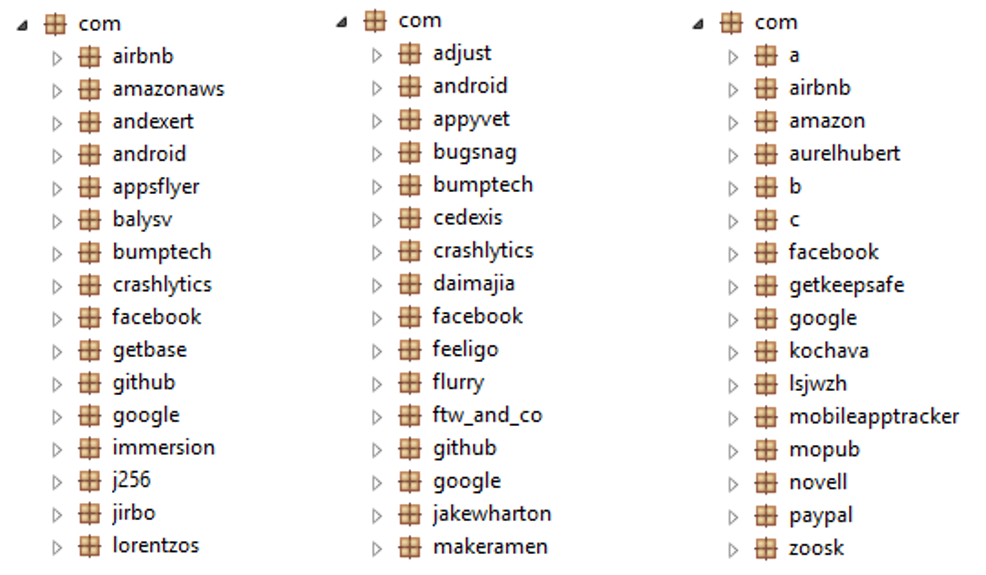

So I decided to take a look at those dating apps with the leaking SDKs to find out why it was happening. It came as no surprise that they were used by more than one third party in these apps – in fact, every app contained at least 40 different modules. They make up a huge part of these apps – at least 75% of the Dalvik bytecode was in third-party modules; in one app the proportion of third-party code was as high as 90%.

Developers often use third-party code to save time and make use of existing functionality. This makes perfect sense and allows developers to focus on their own ideas instead of working on something that has already been developed many times before. However, this means developers are unlikely to know all the details of the third-party code used and it may contain security issues. That’s what happened with the apps from our research.

Getting results

Knowing that there are popular SDKs exposing user data and that almost every app uses several SDKs, we decided to search for more of these apps and SDKs. To do so we used network traffic dumps from our internal Android sandbox. Since 2014 we have collected network activities from more than 13 million APKs. The idea is simple – we install and launch an app and imitate user activity. During app execution we collect logs and network traffic. There is no real user data, but to the app it looks like a real device with a real user.

We searched for the two most popular HTTP requests – GET and POST. In GET requests user data is usually part of the URL parameters, while in POST requests user data is in the Content field of the request, not the URL. In our research, we looked for apps transmitting unencrypted user data using at least one of these requests, though many were exposing user data in both requests.

We were able to identify more than 4 million APKs exposing some data to the internet. Some of them were doing it because their developers had made a mistake, but most of the popular apps were exposing user data because of third-party SDKs. For each type of request (GET or POST) we extracted the domains where apps were transmitting user data. Then we sorted these domains by app popularity – how many users had these apps installed. That’s how we identified the most popular SDKs leaking user data. Most of them were exposing device information, but some were transmitting more sensitive information like GPS coordinates or personal information.

Four most popular domains where apps were exposing sensitive data through GET requests

mopub.com

This domain is part of a popular advertising network. It was used by the two dating apps mentioned at the beginning of this article. We found many more popular apps with this SDK – at least five of them have more than 100 million installations according to Google Play Store and many others with millions of installations.

It transmits the following data in unencrypted form:

- device information (manufacturer name, model, screen resolution)

- network information (MCC, MNC)

- package name of the app

- device coordinates

- Key words

Key words are the most interesting part of the transmitted data. They can vary depending on app parameter settings. In our data there was usually some personal information like name, date of birth and gender. Location needs to be set by an app too – and usually apps provide GPS coordinates to the advertising SDK.

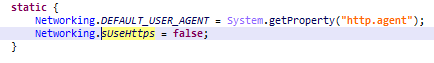

We found several different versions of this SDK. The most common version was able to use HTTPS instead of HTTP. But it needs to be set by the app developers and according to our findings they mostly didn’t bother, leaving the default value HTTP.

rayjump.com

This domain is also part of a popular advertising network. We found two apps with more than 500 million installations, seven apps with more than 100 million installations and many others with millions of installations.

It transmits the following data:

- device information (manufacturer name, model, screen resolution, OS version, device language, time zone, IMEI, MAC)

- network information (MCC, MNC)

- package name of the app

- device coordinates

We should mention that while most of this data was transmitted in plain text as URL parameters, the coordinates, IMEI and MAC address were encoded with Base64. We can’t say they were protected, but at least they weren’t in plain text. We were unable to find any versions of this SDK where it’s possible to use HTTPS – all versions had HTTP URLs hardcoded.

tapas.net

Another popular advertising SDK that collects the same data as the others:

- device information (manufacturer name, model)

- network operator code

- package name of the app

- device coordinates

We found seven apps with more than 10 million installations from Google Play Store and many other apps with fewer installations. We were unable to find any way for the developers to switch from HTTP to HTTPS in this SDK either.

appsgeyser.com

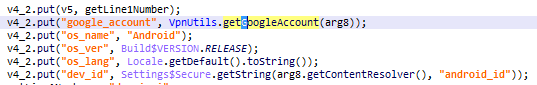

The fourth advertising SDK is appsgeyser and it differs from the others in that it is actually a platform to build an app. It allows people who don’t want to develop an app to simply create one. And that app will have an advertising SDK in it that uses user data in HTTP requests. So, these apps are actually developed by this service and not by developers.

They transmit the following data:

- device information (manufacturer name, model, screen resolution, OS version, android_id)

- network information (operator name, connection type)

- device coordinates

We found a huge amount of apps that have been created with this platform and are using this advertising SDK, but most of them are not very popular. The most popular have just tens of thousands of installations. However, there really are lots of these apps.

According to the appsgeyser.com web page there are more than 6 million apps with almost 2 billion installations between them. And they showed almost 200 billion ads – probably all via HTTP.

Four most popular domains where apps were exposing sensitive data through POST requests

ushareit.com

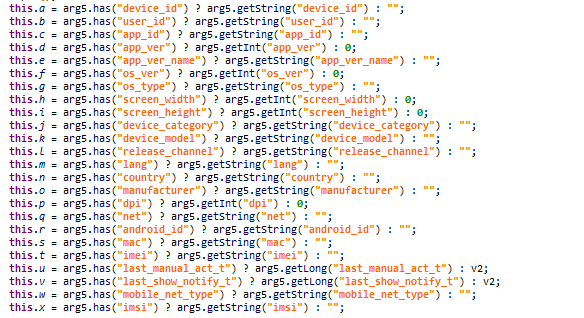

All apps posting unencrypted data to this server were created by the same company, so it isn’t because of third-party code. But these apps are very popular – one of them was installed more than 500 million times from Google Play Store. These apps collect a large amount of device information:

- manufacturer name

- model

- screen resolution

- OS version

- device language

- country

- android_id

- IMEI

- IMSI

- MAC

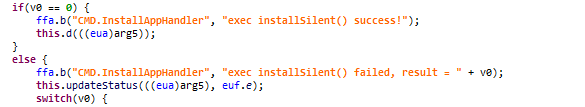

This unencrypted data is then sent to the server. Furthermore, among the data they are uploading is a list of supported commands – one of them is to install an app. The list of commands is transmitted in plain text and the answer from the server is also unencrypted. This means it can be intercepted and modified. What is even worse about this functionality is that the app can silently install a downloaded app. The app just needs to be a system app or have root rights to do so.

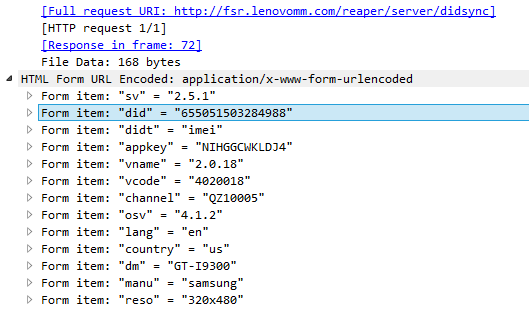

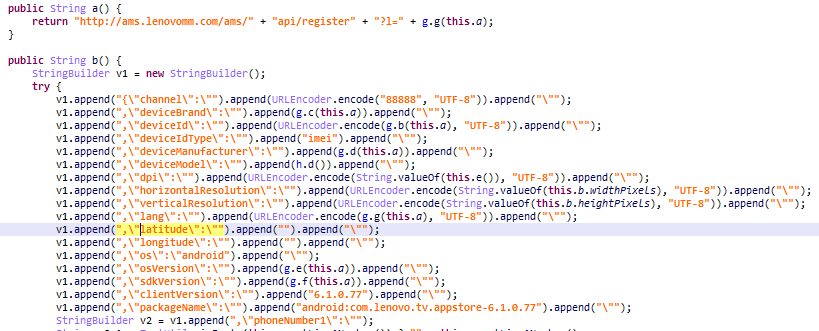

Lenovo

Here is another example of popular apps leaking user data not because of third-party code but because of a mistake by developers. We found several popular Lenovo apps collecting and transmitting unencrypted device information:

- IMEI

- OS version

- language

- manufacturer name

- model

- screen resolution

This information is not very sensitive. But we found several Lenovo apps that were sending more sensitive data in unencrypted form, such as GPS coordinates, phone number and email.

We reported these issues to Lenovo and they fixed everything.

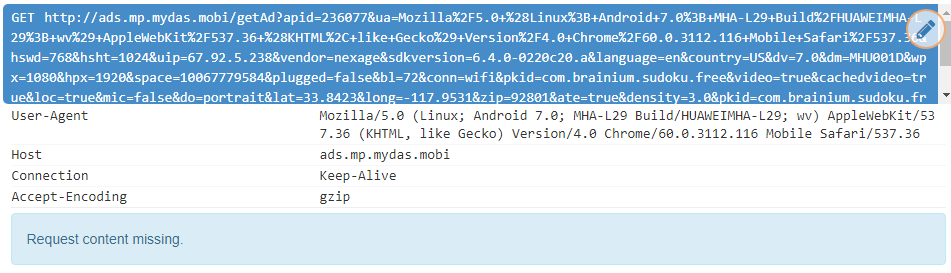

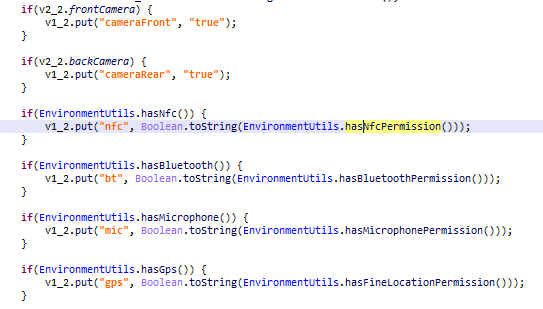

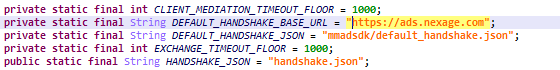

Nexage.com

This domain is used by a very popular advertising SDK. There are tons of apps using it. One of them even has more than 500 million installations and seven other apps have more than 100 million installations. Most of the apps with this SDK are games. There are two interesting things about this SDK – the transmitted data and the protocol used.

This SDK sends the following data to the server:

- device information (screen resolution, storage size, volume, battery level)

- network information (operator name, IP address, connection type, signal strength)

- device coordinates

It also sends information about hardware availability:

- Front/rear camera availability

- NFC permission

- Bluetooth permission

- Microphone permission

- GPS coordinates permission

It may also send some personal information, such as age, income, education, ethnicity, political view, etc. There’s no magic involved – the SDK has no way of finding this information unless the apps that are using this SDK provide it. We have yet to see any app providing these details to the SDK, but we think users should be aware of the risks when entering such details to apps. The information could be passed on to the SDK and the SDK could expose it to the internet.

The second interesting thing about this SDK is that it uses HTTPS to transmit data, but usually only for the initial communication. After that it may receive new configuration settings from the server that specify an HTTP URL. At least that’s what happened on my device and several other times with different apps on our test devices.

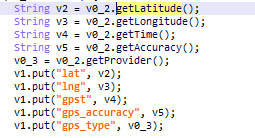

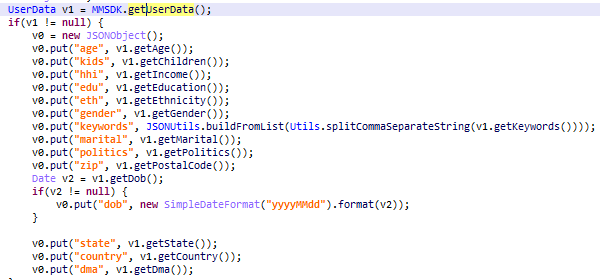

Quantumgraph.com

Another SDK that is leaking data uses the quantumgraph.com domain. This is an analytics SDK, not an advertising one. We found two apps with more than 10 million installations from Google Play Store and another seven apps with more than a million installations. More than 90% of detected users with this SDK were from India.

This SDK posts JSON files with data via HTTP. The data may vary from app to app because it’s an analytics SDK and it sends information provided by the app. In most cases, the following items are among the sent data:

- Device information

- Personal information

- Device coordinates

- App usage

In the case of the dating app, there were likes, swipes and visited profiles – all user activity.

This SDK was using a hardcoded HTTP URL, but after our report they created a version with an HTTPS URL. However, most apps are still using the old HTTP version.

Other SDKs

Of course, there are other SDKs using HTTP to transmit user data, but they are less popular and almost identical to those described above. Many of them expose device locations, while some also expose emails and phone numbers.

Other findings

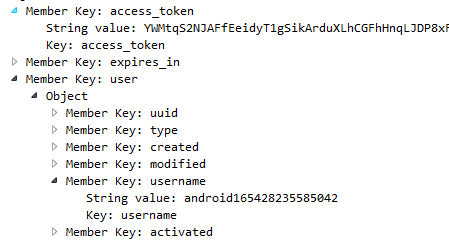

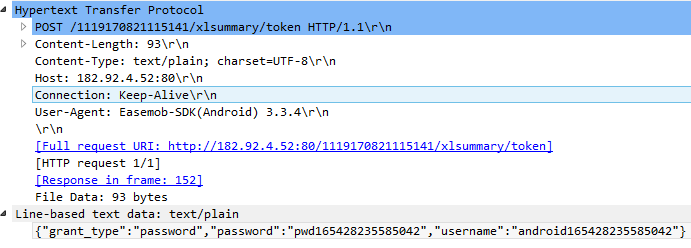

During our research, we found many apps that were transmitting unencrypted authentication details via HTTP. We were surprised to discover how many apps are still using HTTP to authenticate their services.

They weren’t always transmitting user credentials – sometimes they were credentials for their services (for example databases) too. It makes no sense having credentials for such services because they are exposed to the internet. Such apps usually transmit authentication tokens, but we saw unencrypted logins and passwords too.

Malware

Digging into an HTTP request with unencrypted data allowed us to discover a new malicious site. It turns out that many malicious apps use HTTP to transmit user data too. And in the case of malware it is even worse because it can steal more sensitive data like SMSs, call history, contacts, etc. Malicious apps not only steal user data but expose it to the internet making it available for others to exploit and sell.

Leaked data

In this research we analyzed the network activity of more than 13 million APK files in our sandbox. On average, approximately every fourth app with network communications was exposing some user data. The fact that there are some really popular apps transmitting unencrypted user data is significant. According to Kaspersky Lab statistics, on average every user has more than 100 installed apps, including system and preinstalled apps, so we presume most users are affected.

In most cases these apps were exposing:

- IMEI, International Mobile Equipment Identities (unique phone module id) which users can’t reset unless they change their device.

- IMSI, International Mobile Subscriber Identities (unique SIM card id) which users can’t reset unless they change their SIM card.

- Android ID – a number randomly generated during the phone’s setup, so users can change it by resetting their device to factory settings. But from Android 8 onwards there will be a randomly generated number for every app, user and device.

- Device information such as the manufacturer, model, screen resolution, system version and app name.

- Device location.

Some apps expose personal information, mostly the user’s name, age and gender, but it can even include the user’s income. Their phone number and email address can also be leaked.

Why is it wrong?

Because this data can be intercepted. Anyone can intercept it on an unprotected Wi-Fi connection, the network owner could intercept it, and your network operator could find out everything about you. Data will be transmitted through several network devices and can be read on any of them. Even your home router can be infected – there are many examples of malware infecting home routers.

Without encryption this data is being exposed as plain text and can be simply extracted from the requests. By knowing the IMSI and IMEI anyone can track your data from different sources – you need to change both the SIM card and device at the same time to change them. Armed with these numbers, anyone can collect the rest of your leaking data.

Furthermore, HTTP data can be modified. Someone could change the ads being displayed or, even worse, change the link to an app. Because some advertising networks promote apps and ask users to install them, it could result in malware being downloaded instead of the requested app.

Apps can intercept HTTP traffic and bypass the Android permission system. Android uses permissions to protect users from unexpected app activity. This involves apps declaring what access they will need. Starting from Android 6, all permissions have been divided into two groups – normal and dangerous. If an app needs dangerous permissions, it has to ask the user for permission in runtime, not just before installation. So, in order to get the location, the app will need to ask the user to grant access. And to read the IMEI or IMSI the app will also need to ask the user for access, because this is classified as a dangerous permission.

But an app can add a proxy to Wi-Fi settings and read all the data being transmitted from other apps. To do so it needs to be a system app or be provisioned as the Profile or Device Owner. Or an app can set a VPN service on the device transmitting user data to its server. After that the app can find out the device’s location without accessing it just by reading the HTTP requests.

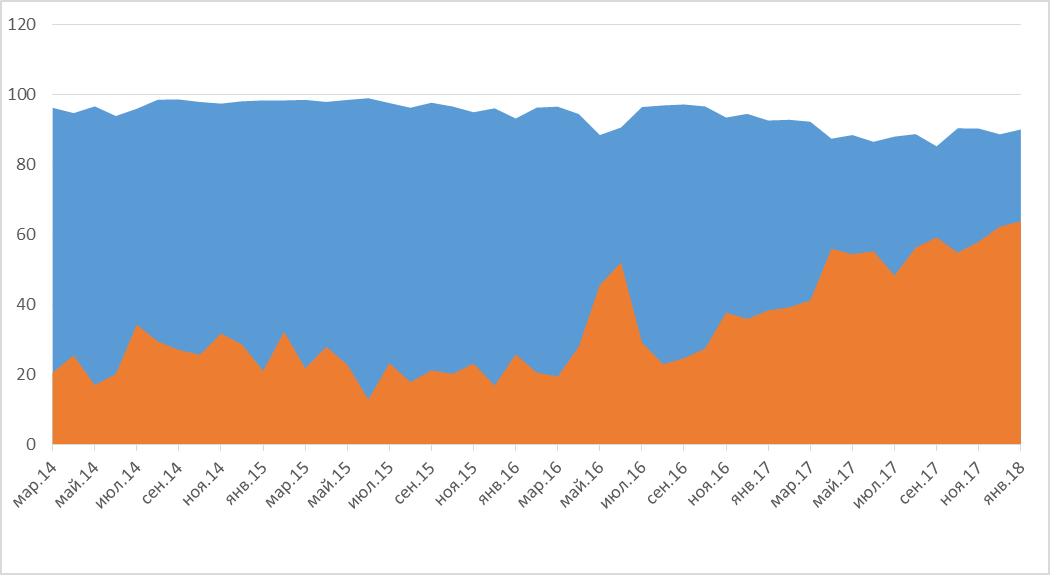

Future

Starting from the second half of 2016, more and more apps have been switching from HTTP to HTTPS. So, we are moving in the right direction, but too slowly. As of January 2018, 63% of apps are using HTTPS but most of them are still also using HTTP. Almost 90% of apps are using HTTP. And many of them are transmitting unencrypted sensitive data.

Advice for developers

- Do not use HTTP. You can expose user data, which is really bad.

- Turn on 301 redirection to HTTPS for your frontends.

- Encrypt data. Especially if you have to use HTTP. Asymmetric cryptography works great.

- Always use the latest version of an SDK. Even if it means additional testing before the release. This is really important because some security issues could be fixed. From what we have seen, many apps do not update third-party SDKs, using outdated versions instead.

- Check your app’s network communications before publishing. It won’t take more than a few minutes but you will be able to find out if any of your SDKs are switching from HTTPS to HTTP and exposing user data.

Advice for users

- Check your app permissions. Do not grant access to something if you don’t understand why. Most apps do not need access to your location. So don’t grant it.

- Use a VPN. It will encrypt the network traffic between your device and external servers. It will remain unencrypted behind the VPN’s servers, but at least it’s an improvement.

Leaking ads

Erik Derr

Interesting findings! Absolutely in line with our research on library detection and security/privacy of online app generators (e.g. Apps Geyser). Do you have more details on the SDKs and versions that leak data?

Dorrie

Read this quite by chance. As a mere mortal I was horrified to learn some of this – thinking I was safe. Hoping my Kaspersky is doing its job, also camera covered over as I can’t understand why it keeps telling me it is in use!

Anonymous

“Turn on 301 redirection to HTTPS for your frontends.”

301 works, but in order to reduce the chances of an SSL stripping attack, HSTS is better.

Charles

I’d like to suggest option #3 at the bottom, for users, namely: Install an ad-blocker on your phones and computers.

Poor security of advertising gets passed on to the end user, who has limited means to deal with the fallout of endless data breaches or the annoyances of retargeting.

Until the ad agencies get serious about security, the ad blockers will solve their security problems for them, permanently. The sooner, the better.