Kaspersky Lab’s many years of cyberthreat research would suggest that any device with access to the Internet will inevitably be hacked. In recent years, we have seen hacked toys, kettles, cameras, and irons. It would seem that no gadget has escaped the attention of hackers, yet there is one last bastion: “smart” devices for animals. For example, trackers to monitor their location. Such gadgets can have access to the owner’s home network and phone, and their pet’s location.

This report highlights the potential risks for users and manufacturers. In it, we examine several trackers for potential vulnerabilities. For the study, we chose some popular models that have received positive reviews:

- Kippy Vita

- LINK AKC Smart Dog Collar

- Nuzzle Pet Activity and GPS Tracker

- TrackR bravo and pixel

- Tractive GPS Pet Tracker

- Weenect WE301

- Whistle 3 GPS Pet Tracker & Activity Monitor

Technologies used: Bluetooth LE

The four trackers in the study use Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), which in many cases is the weak spot in the device’s protective armor. Let’s take a closer look at this technology. BLE is an energy-saving Bluetooth specification widely used in IoT devices. What we’re interested in is the lack of authentication and the availability of services and characteristics.

Unlike “classic” Bluetooth, where peer devices are connected using a PIN code, BLE is aimed at non-peer devices, one of which may not have a screen or keyboard. Thus, PIN code protection is not implemented in BLE — authentication depends entirely on the developers of the device, and experience shows that it is often neglected.

The second feature of interest to us is the availability of services, characteristics, and descriptors. They form the basis for data transfer between devices in the BLE specification. As we already noted, BLE works with non-peer devices, one of which (the one that does the connecting) is usually a smartphone. The other device, in our case, is a tracker. After connecting to it, several BLE services are available to the smartphone. Each of them contains characteristics which in turn may have descriptors. Both characteristics and descriptors can be used for data transfer.

Hence, the correct approach to device security in the case of BLE involves pre-authentication before characteristics and descriptors are made available for reading and writing. Moreover, it is good practice to break the link shortly after connecting if the pre-authentication stage is not passed. In this case, authentication should be based on something secret that is not accessible to the attacker—for example, the first part of the data can be encrypted with a specific key on the server (rather than the app) side. Or transmitted data and the MAC address of the connected device can be confirmed via additional communication channels, for example, a built-in SIM card.

Kippy Vita

This tracker transfers GPS coordinates to the server via its built-in SIM card, and the pet’s location is displayed in the mobile app. The tracker does not interface “directly” with the smartphone. We could not detect any problems in the device itself, so we turned our focus to the mobile apps.

Here, too, everything looked pretty good: SSL Pinning was implemented, unlike in any other app we tested. Moreover, the Android app encrypts important data before saving it to its own folder.

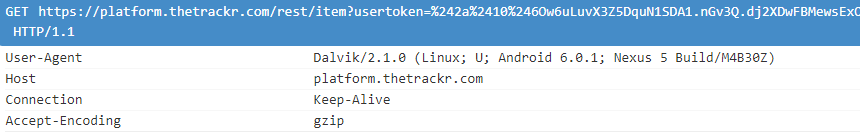

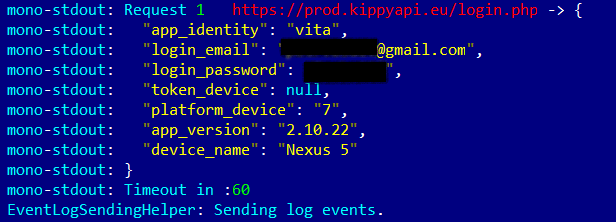

The only problem we did detect was that the app for Android logs data that is transmitted to the server. This data can include the user’s password and login, as well as an authentication token.

Output of the Kippy Vita app with user login and password

Despite the fact that not all apps can read logs (only system apps or ones with superuser rights), it is still a major security issue.

Registered CVE:

CVE-2018-9916

Link AKC

This tracker monitors the pet’s location via GPS and transfers coordinates via the built-in SIM card. What’s more, it can interface with the owner’s phone directly — via Bluetooth LE. And this means that it is always ready to connect devices, which makes a good starting point for the study.

We were pleasantly surprised by Link AKC: the developers did everything right in terms of securing the connection to the smartphone. We couldn’t find any major problems, which is rare for devices with BLE support.

After the smartphone connects to the device and discovers services, it should enable notifications (that is, inform the tracker of expected changes) in two characteristics and a descriptor (otherwise the tracker breaks the link). After that Link AKC is ready to receive commands. They should contain the user ID; if the user does not have rights to use the tracker, the command is not executed. This maintains control over access rights. Even using the ID obtained from the tested device, we could not make the gadget execute a command from another smartphone—it appears that the tracker checks the smartphone’s MAC address.

However, the device cannot be described as completely secure. In the app for Android, we found that the developers had forgotten to disable logging. As a result, the app transfers lots of data to logcat, including:

- the app’s authorization token, which if intercepted can be used to sign into the service and discover the pet’s location:

- User registration data, including name and email address:

- Device coordinates:

Starting with Android 4.1, only some system apps or apps with superuser rights can read the logs of other programs. It is also possible to gain access when connecting the smartphone to a computer, but this requires Android developer mode to be activated.

Despite these restrictions, it is still a problem: attackers can get hold of data to access the victim’s account, even if the likelihood of this happening is small.

On top of that, the Android app does not verify the server’s HTTPS certificate, exposing it to man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks. For a successful attack, attackers need only install their own certificate on the smartphone (which is quite simple to do), allowing them to intercept all transmitted data, including passwords and tokens used for account access:

The Link AKC app for Android is vulnerable to MITM attacks

The authorization token is also stored in unencrypted form in the app folder. Although superuser rights are needed to access it, it is still not the best place to store important data.

The authorization token is stored in unencrypted form

The authorization token is stored in unencrypted form

Registered CVE:

CVE-2018-7041

Nuzzle

In terms of functionality, Nuzzle is like the previous tracker: It too uses a SIM card to transmit the pet’s GPS coordinates and can directly connect to a smartphone via BLE. But on the latter point, Nuzzle performed less well than Link AKC: the lack of authorization and access control means that the device is ready to interface with any smartphone. This lets an attacker take control of the device, just like the owner. For example, it can quickly discharge the battery by turning on the light bulb (for which the value of just one attribute needs changing).

An attacker can receive data from the device as soon as a connection is made. Data is available in two characteristics: one contains telemetry information, including device location, while the other provides device status information (in particular, temperature and battery charge).

What is worse, the continuous reading of data from the telemetry characteristic results in the device being “lost”: to save battery power, the gadget does not transmit coordinates via the mobile network if they have already been sent via BLE. Thus, it is possible to conceal the location of the pet simply by connecting to the tracker using a smartphone.

We detected another security hole in the process of updating the device firmware. The integrity control was found to be easy to bypass. Basically, the firmware consists of two files with the extensions DAT and BIN. The first contains information about the firmware, including the checksum (CRC16) used in the integrity control, and the second contains the firmware itself. All it takes to install modified software on the tracker is to change the checksum in the DAT file.

![]()

AT commands in Nuzzle firmware

To cripple the device, we didn’t even need to analyze the firmware: it is not encrypted or packed, so just by opening it in a hex editor we were able to find the AT commands and the host used to send data by means of the SIM card. After we changed several bytes in the host, updated the firmware checksum, and uploaded it to the device, the tracker stopped working.

As in the case of Link AKC, the Nuzzle app for Android does not check the server certificate, and the authentication token and user email address are stored in the app folder in unencrypted form.

Unencrypted authorization token and user email address

Registered CVE:

CVE-2018-7043

CVE-2018-7042

CVE-2018-7045

CVE-2018-7044

TrackR

Two TrackR devices featured in our study: Bravo and Pixel. These “trinkets” differ from previous devices in that their tracking range (if indeed they are intended to track pets) is limited to 100 meters: unlike other models, they have no GPS module or SIM card, and the only link to them is via Bluetooth LE. Their main purpose is to locate keys, remote controls, etc. around the apartment. However, the developers have equipped the devices with an option that lets them partially track the movements of something: the trackers location can be transmitted “via” the smartphones of other TrackR app users. If the app is running on the smartphone, it will transfer data to the service about all “trinkets” detected nearby, together with the smartphone coordinates. Therein lies the first defect: anyone can sign into the mobile app and send fake coordinates.

We managed to identify a few more problems, but as it turned out, most of them had already been discovered by our colleagues at Rapid7. Although their research was published more than a year ago, some vulnerabilities had yet to be fixed at the time of penning this article.

For instance, the devices have no authentication when connecting via Bluetooth LE, which means they are open to intruders. An attacker could easily connect and turn on the audio signal, for example, simply by changing the value of one characteristics. This could let an attacker find the animal before its owner does or run down the tracker battery.

Structure of TrackR services and attributes

Structure of TrackR services and attributes

Besides, the app for Android does not verify server certificates, meaning that an MITM attack could lead to the interception of the password, authentication token, user email address, and device coordinates.

TrackR Android app requests contain an authentication token

TrackR Android app requests contain an authentication token

On the bright side, the app does not store the authentication token or password in their own folder, which is the proper way to guard against Trojans that use superuser rights to steal data.

Registered CVE:

CVE-2018-7040

CVE-2016-6541

Tractive

Unlike most devices we studied, this tracker does not communicate directly with the smartphone—only through its own servers. This approach is secure enough, but we detected some minor issues in the Android app. First, as in other cases, it does not verify the server certificate, which facilitates MITM attacks. What’s more, the app stores the authentication token in unencrypted form:

As well as pet movement data:

It should be noted that this data is not so easy to steal, since other apps cannot read it. But there are Trojans that can steal data from other apps by exploiting superuser rights.

Update from 31.05.2018:

After the publication of our research, the vendor contacted us and let us know that an updated app has been available from February this year. We checked the app and can confirm that the vendor has added SSL-pinning to their app making the MitM attack impossible. The unencrypted token issue is still in place in the updated version. We appreciate the vendor’s efforts in making its products more secure.

Weenect WE301

This is another tracker that doesn’t interface with the owner’s smartphone directly, but transfers pet coordinates to the server via a built-in SIM card. We didn’t encounter any security issues with this tracker, but problems similar to those in Tractive were detected in the Android version of the app.

First, it does not prevent MITM attacks, allowing attackers to access the user’s account or intercept geoinformation. Second, authentication data is stored in the app folder in unencrypted form, exposing it to Trojans with superuser rights on the device.

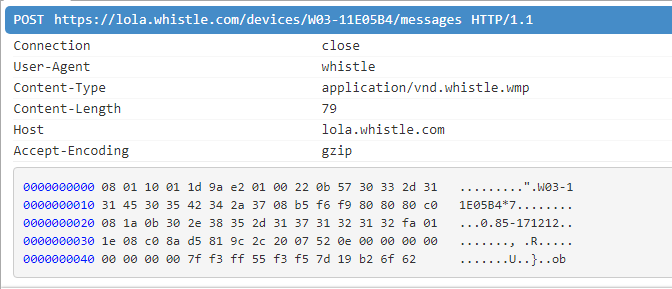

Whistle 3

This is one of the most technically interesting trackers in the study. It can transfer GPS coordinates via its built-in SIM card, via Wi-Fi to its server (if the owner provides a Wi-Fi network password), or directly to the owner’s smartphone via BLE.

We looked at Wi-Fi first of all and found that the developers had taken care to secure the connection: The device transmits small portions of data over HTTPS (that is, in encrypted form).

Wi-Fi data transfer is secured using HTTPS

Wi-Fi data transfer is secured using HTTPS

Next, we checked the BLE connection and found many security issues. The first is the lack of proper authentication. After connecting, the device waits for a certain sequence of actions to be performed, which could be described as pre-authentication. The sequence is so simple that a third party can easily reproduce it. All it takes is to connect to the device, transfer two characteristics to WRITE_TYPE_NO_RESPONSE mode, request a change in the size of transmitted data (MTU), turn on notifications for one characteristics, and transfer a certain number to another characteristics.

Now the tracker is ready to receive and execute commands that do not contain a user ID, which means that anyone can send them. For example, it is possible to send an initiateSession command, and in response the device will send an unencrypted set of data, including the device coordinates. What’s more, if this command is continuously transmitted, the gadget will not send location data via the SIM card, since it will assume that such data has already been received “directly.” Thus, it is possible to “hide” the tracker from its owner.

There is one more problem: the tracker transmits data to the server without any authentication. This means that anyone can substitute it, altering the coordinates in the process.

The app transmits data received from the tracker via BLE

The app transmits data received from the tracker via BLE

The Android app uses the HTTPS protocol (which is good), but does not verify the server certificate.

MITM attacks can intercept user data

MITM attacks can intercept user data

Not only that, the smartphone app stores user data in unencrypted form in its own folder, exposing it to theft by a Trojan with superuser rights. However, authentication data is stored correctly.

Tracker coordinates from the app database

Tracker coordinates from the app database

Note that the Android app writes data to logcat. As mentioned above, despite the fact that other app logs can read only some system utilities or apps with superuser rights, there is no need to write important data to the log.

The Android app can log user and pet data (activity, email address, name, owner’s phone number), as well as one of the used tokens

The Android app can log user and pet data (activity, email address, name, owner’s phone number), as well as one of the used tokens

Registered CVE:

CVE-2018-8760

CVE-2018-8757

CVE-2018-8759

CVE-2018-9917

Conclusions

GPS trackers have long been applied successfully in many areas, but using them to track the location of pets is a step beyond their traditional scope of application for this, they need to be upgraded with new “user communication interfaces” and “trained” to work with cloud services, etc. If security is not properly addressed, user data becomes accessible to intruders, endangering both users and pets.

Research results: four trackers use Bluetooth LE technology to communicate with the owner’s smartphone, but only one does so correctly. The rest can receive and execute commands from anyone. Moreover, they can be disabled or hidden from the owner—all that’s required is proximity to the tracker.

Just one of the tested Android apps verifies the certificate of its server, without relying solely on the system. As a result, they are vulnerable to MITM attacks—intruders can intercept transmitted data by “persuading” victims to install their certificate.

I know where your pet is

Denis Mathieu

Finalement, tout ce que j’ai lu me dis tout simplement “ce n’est pas une bonne idée d’acheter un tracker pour mon chien. Dans tous ceux évalués il n’y en a pas un meilleurs que les autres