Investigating the security of online dating apps

It seems just about everyone has written about the dangers of online dating, from psychology magazines to crime chronicles. But there is one less obvious threat not related to hooking up with strangers – and that is the mobile apps used to facilitate the process. We’re talking here about intercepting and stealing personal information and the de-anonymization of a dating service that could cause victims no end of troubles – from messages being sent out in their names to blackmail. We took the most popular apps and analyzed what sort of user data they were capable of handing over to criminals and under what conditions.

We studied the following online dating applications:

- Tinder for Android and iOS

- Bumble for Android and iOS

- OK Cupid for Android and iOS

- Badoo for Android and iOS

- Mamba for Android and iOS

- Zoosk for Android and iOS

- Happn for Android and iOS

- WeChat for Android and iOS

- Paktor for Android and iOS

By de-anonymization we mean the user’s real name being established from a social media network profile where use of an alias is meaningless.

User tracking capabilities

First of all, we checked how easy it was to track users with the data available in the app. If the app included an option to show your place of work, it was fairly easy to match the name of a user and their page on a social network. This in turn could allow criminals to gather much more data about the victim, track their movements, identify their circle of friends and acquaintances. This data can then be used to stalk the victim.

Discovering a user’s profile on a social network also means other app restrictions, such as the ban on writing each other messages, can be circumvented. Some apps only allow users with premium (paid) accounts to send messages, while others prevent men from starting a conversation. These restrictions don’t usually apply on social media, and anyone can write to whomever they like.

More specifically, in Tinder, Happn and Bumble users can add information about their job and education. Using that information, we managed in 60% of cases to identify users’ pages on various social media, including Facebook and LinkedIn, as well as their full names and surnames.

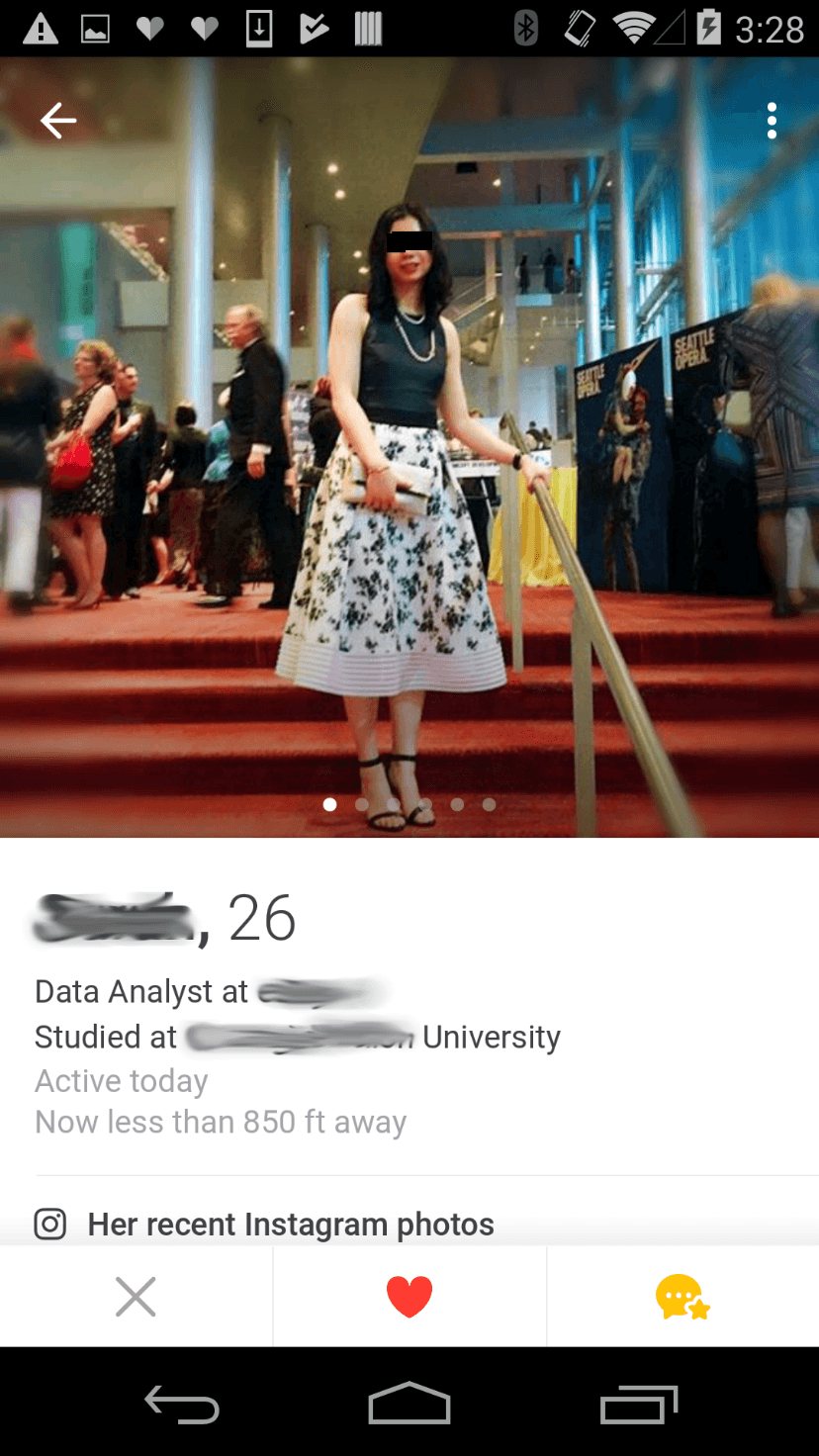

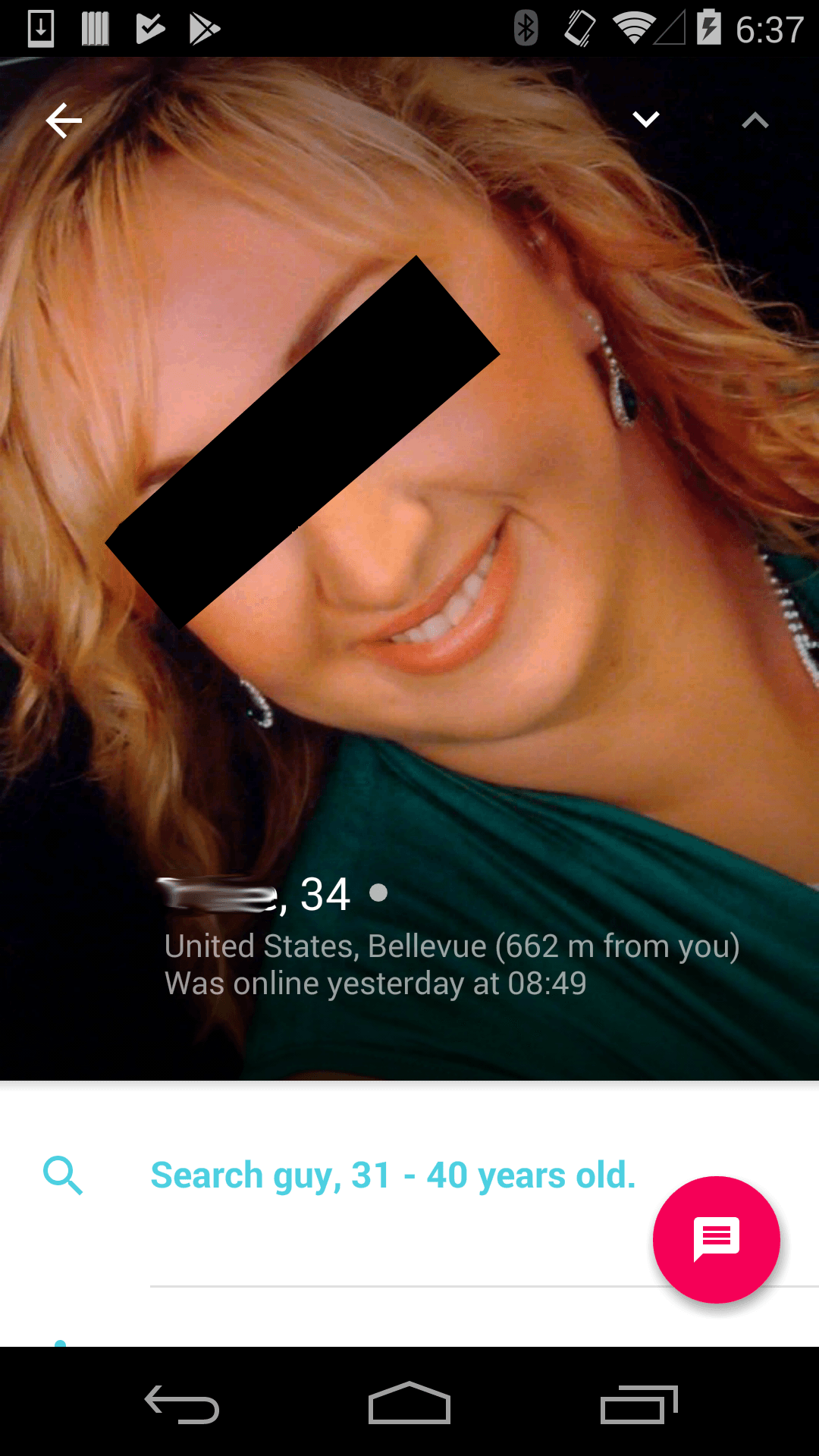

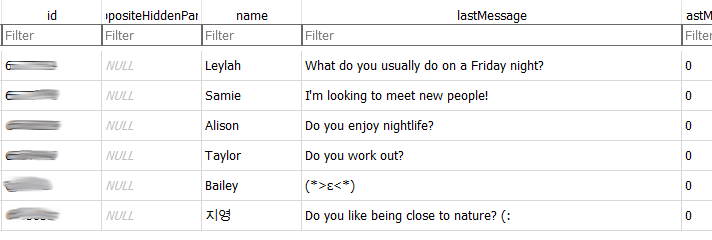

An example of an account that gives workplace information that was used to identify the user on other social media networks

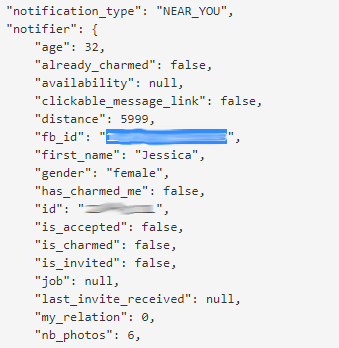

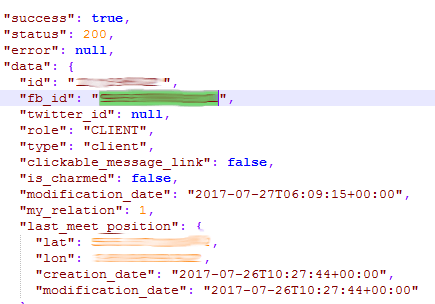

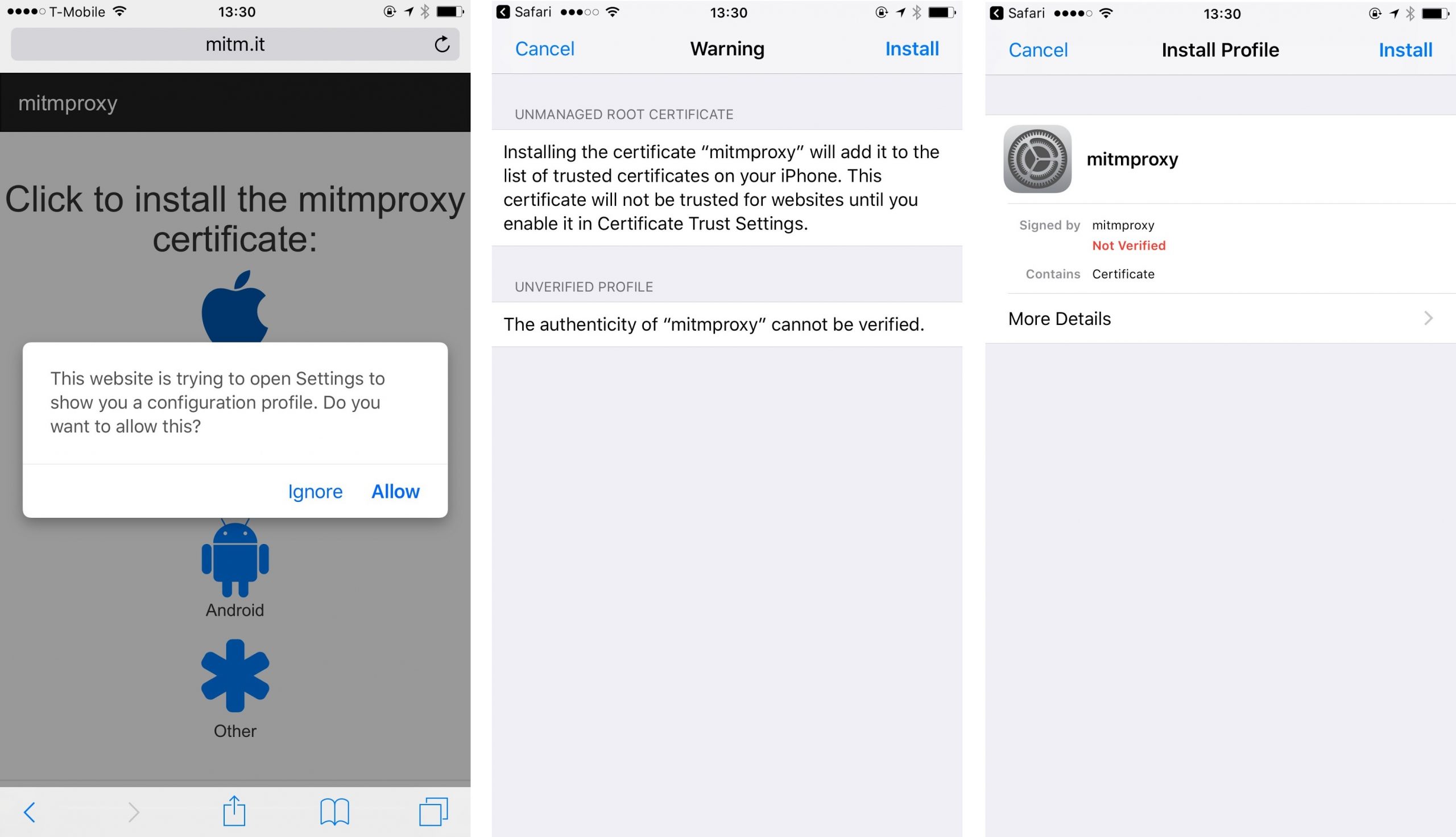

In Happn for Android there is an additional search option: among the data about the users being viewed that the server sends to the application, there is the parameter fb_id – a specially generated identification number for the Facebook account. The app uses it to find out how many friends the user has in common on Facebook. This is done using the authentication token the app receives from Facebook. By modifying this request slightly – removing some of the original request and leaving the token – you can find out the name of the user in the Facebook account for any Happn users viewed.

It’s even easier to find a user account with the iOS version: the server returns the user’s real Facebook user ID to the application.

Information about users in all the other apps is usually limited to just photos, age, first name or nickname. We couldn’t find any accounts for people on other social networks using just this information. Even a search of Google images didn’t help. In one case the search recognized Adam Sandler in a photo, despite it being of a woman that looked nothing like the actor.

The Paktor app allows you to find out email addresses, and not just of those users that are viewed. All you need to do is intercept the traffic, which is easy enough to do on your own device. As a result, an attacker can end up with the email addresses not only of those users whose profiles they viewed but also for other users – the app receives a list of users from the server with data that includes email addresses. This problem is found in both the Android and iOS versions of the app. We have reported it to the developers.

Some of the apps in our study allow you to attach an Instagram account to your profile. The information extracted from it also helped us establish real names: many people on Instagram use their real name, while others include it in the account name. Using this information, you can then find a Facebook or LinkedIn account.

Location

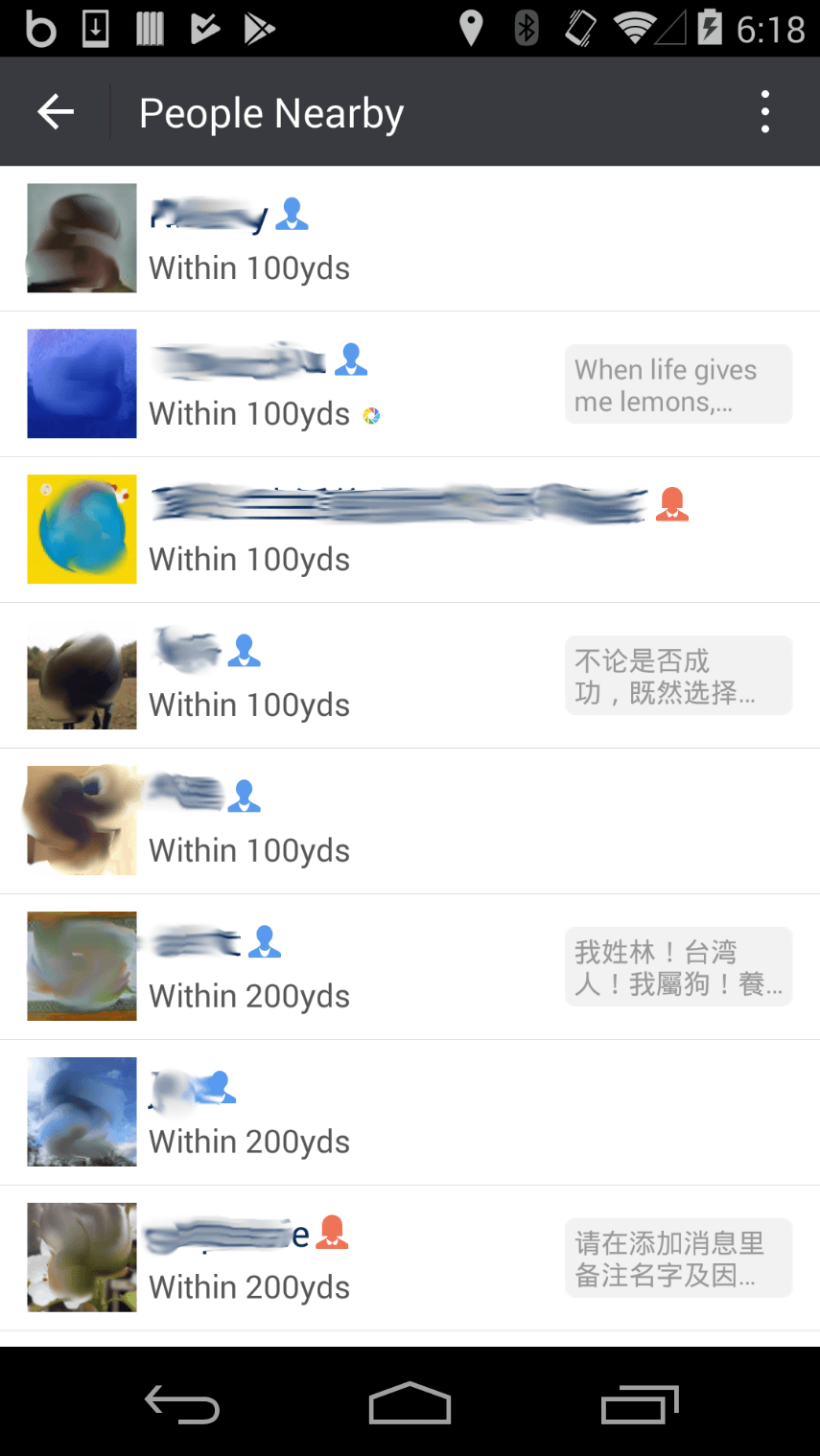

Most of the apps in our research are vulnerable when it comes to identifying user locations prior to an attack, although this threat has already been mentioned in several studies (for instance, here and here). We found that users of Tinder, Mamba, Zoosk, Happn, WeChat, and Paktor are particularly susceptible to this.

The attack is based on a function that displays the distance to other users, usually to those whose profile is currently being viewed. Even though the application doesn’t show in which direction, the location can be learned by moving around the victim and recording data about the distance to them. This method is quite laborious, though the services themselves simplify the task: an attacker can remain in one place, while feeding fake coordinates to a service, each time receiving data about the distance to the profile owner.

Different apps show the distance to a user with varying accuracy: from a few dozen meters up to a kilometer. The less accurate an app is, the more measurements you need to make.

Unprotected transmission of traffic

During our research, we also checked what sort of data the apps exchange with their servers. We were interested in what could be intercepted if, for example, the user connects to an unprotected wireless network – to carry out an attack it’s sufficient for a cybercriminal to be on the same network. Even if the Wi-Fi traffic is encrypted, it can still be intercepted on an access point if it’s controlled by a cybercriminal.

Most of the applications use SSL when communicating with a server, but some things remain unencrypted. For example, Tinder, Paktor and Bumble for Android and the iOS version of Badoo upload photos via HTTP, i.e., in unencrypted format. This allows an attacker, for example, to see which accounts the victim is currently viewing.

The Android version of Paktor uses the quantumgraph analytics module that transmits a lot of information in unencrypted format, including the user’s name, date of birth and GPS coordinates. In addition, the module sends the server information about which app functions the victim is currently using. It should be noted that in the iOS version of Paktor all traffic is encrypted.

The unencrypted data the quantumgraph module transmits to the server includes the user’s coordinates

Although Badoo uses encryption, its Android version uploads data (GPS coordinates, device and mobile operator information, etc.) to the server in an unencrypted format if it can’t connect to the server via HTTPS.

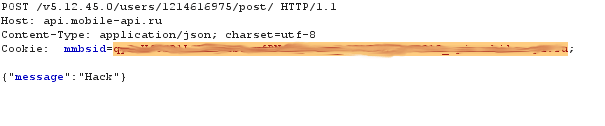

The Mamba dating service stands apart from all the other apps. First of all, the Android version of Mamba includes a flurry analytics module that uploads information about the device (producer, model, etc.) to the server in an unencrypted format. Secondly, the iOS version of the Mamba application connects to the server using the HTTP protocol, without any encryption at all.

This makes it easy for an attacker to view and even modify all the data that the app exchanges with the servers, including personal information. Moreover, by using part of the intercepted data, it is possible to gain access to account management.

Despite data being encrypted by default in the Android version of Mamba, the application sometimes connects to the server via unencrypted HTTP. By intercepting the data used for these connections, an attacker can also get control of someone else’s account. We reported our findings to the developers, and they promised to fix these problems.

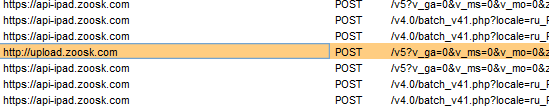

We also managed to detect this in Zoosk for both platforms – some of the communication between the app and the server is via HTTP, and the data is transmitted in requests, which can be intercepted to give an attacker the temporary ability to manage the account. It should be noted that the data can only be intercepted at that moment when the user is loading new photos or videos to the application, i.e., not always. We told the developers about this problem, and they fixed it.

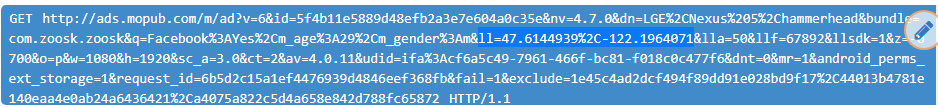

In addition, the Android version of Zoosk uses the mobup advertising module. By intercepting this module’s requests, you can find out the GPS coordinates of the user, their age, sex, model of smartphone – all this is transmitted in unencrypted format. If an attacker controls a Wi-Fi access point, they can change the ads shown in the app to any they like, including malicious ads.

The iOS version of the WeChat app connects to the server via HTTP, but all data transmitted in this way remains encrypted.

Data in SSL

In general, the apps in our investigation and their additional modules use the HTTPS protocol (HTTP Secure) to communicate with their servers. The security of HTTPS is based on the server having a certificate, the reliability of which can be verified. In other words, the protocol makes it possible to protect against man-in-the-middle attacks (MITM): the certificate must be checked to ensure it really does belong to the specified server.

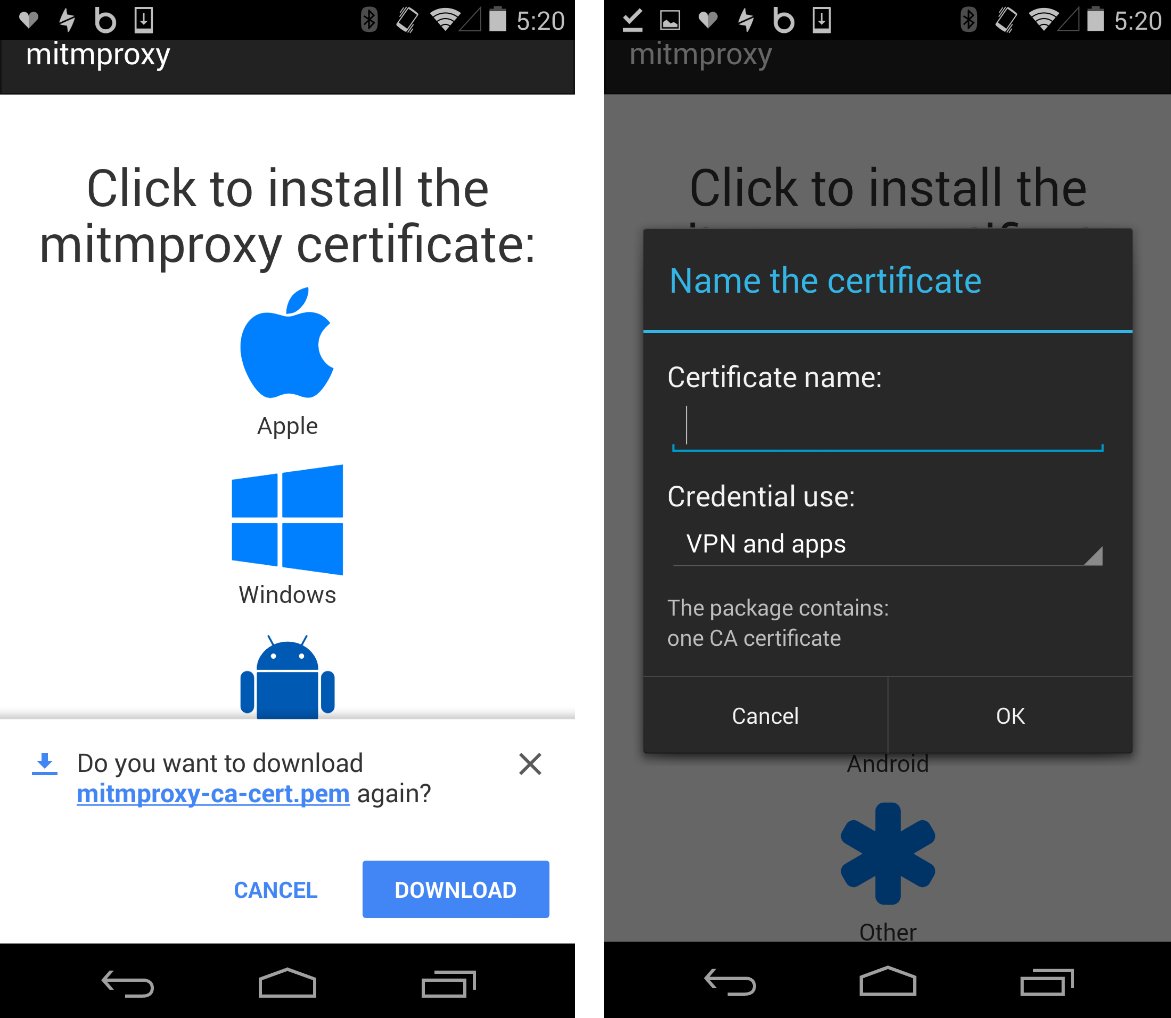

We checked how good the dating apps are at withstanding this type of attack. This involved installing a ‘homemade’ certificate on the test device that allowed us to ‘spy on’ the encrypted traffic between the server and the application, and whether the latter verifies the validity of the certificate.

It’s worth noting that installing a third-party certificate on an Android device is very easy, and the user can be tricked into doing it. All you need to do is lure the victim to a site containing the certificate (if the attacker controls the network, this can be any resource) and convince them to click a download button. After that, the system itself will start installation of the certificate, requesting the PIN once (if it is installed) and suggesting a certificate name.

Everything’s a lot more complicated with iOS. First, you need to install a configuration profile, and the user needs to confirm this action several times and enter the password or PIN number of the device several times. Then you need to go into the settings and add the certificate from the installed profile to the list of trusted certificates.

It turned out that most of the apps in our investigation are to some extent vulnerable to an MITM attack. Only Badoo and Bumble, plus the Android version of Zoosk, use the right approach and check the server certificate.

It should be noted that though WeChat continued to work with a fake certificate, it encrypted all the transmitted data that we intercepted, which can be considered a success since the gathered information can’t be used.

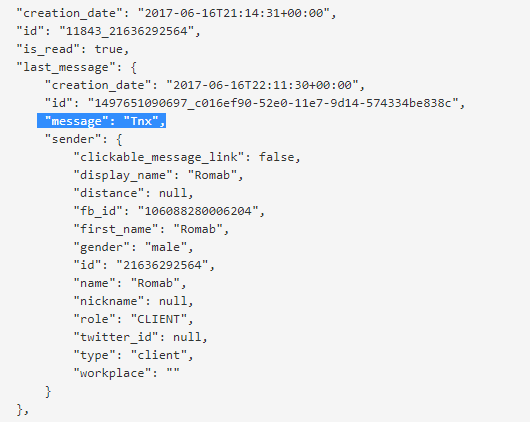

Remember that most of the programs in our study use authorization via Facebook. This means the user’s password is protected, though a token that allows temporary authorization in the app can be stolen.

A token is a key used for authorization that is issued by the authentication service (in our example Facebook) at the request of the user. It is issued for a limited time, usually two to three weeks, after which the app must request access again. Using the token, the program gets all the necessary data for authentication and can authenticate the user on its servers by simply verifying the credibility of the token.

It’s interesting that Mamba sends a generated password to the email address after registration using the Facebook account. The same password is then used for authorization on the server. Thus, in the app, you can intercept a token or even a login and password pairing, meaning an attacker can log in to the app.

App files (Android)

We decided to check what sort of app data is stored on the device. Although the data is protected by the system, and other applications don’t have access to it, it can be obtained with superuser rights (root). Because there are no widespread malicious programs for iOS that can get superuser rights, we believe that for Apple device owners this threat is not relevant. So only Android applications were considered in this part of the study.

Superuser rights are not that rare when it comes to Android devices. According to KSN, in the second quarter of 2017 they were installed on smartphones by more than 5% of users. In addition, some Trojans can gain root access themselves, taking advantage of vulnerabilities in the operating system. Studies on the availability of personal information in mobile apps were carried out a couple of years ago and, as we can see, little has changed since then.

Analysis showed that most dating applications are not ready for such attacks; by taking advantage of superuser rights, we managed to get authorization tokens (mainly from Facebook) from almost all the apps. Authorization via Facebook, when the user doesn’t need to come up with new logins and passwords, is a good strategy that increases the security of the account, but only if the Facebook account is protected with a strong password. However, the application token itself is often not stored securely enough.

Using the generated Facebook token, you can get temporary authorization in the dating application, gaining full access to the account. In the case of Mamba, we even managed to get a password and login – they can be easily decrypted using a key stored in the app itself.

Most of the apps in our study (Tinder, Bumble, OK Cupid, Badoo, Happn and Paktor) store the message history in the same folder as the token. As a result, once the attacker has obtained superuser rights, they will have access to correspondence.

In addition, almost all the apps store photos of other users in the smartphone’s memory. This is because apps use standard methods to open web pages: the system caches photos that can be opened. With access to the cache folder, you can find out which profiles the user has viewed.

Conclusion

Having gathered together all the vulnerabilities found in the studied dating apps, we get the following table:

| App | Location | Stalking | HTTP (Android) | HTTP (iOS) | HTTPS | Messages | Token |

| Tinder | + | 60% | Low | Low | + | + | + |

| Bumble | – | 50% | Low | NO | – | + | + |

| OK Cupid | – | 0% | NO | NO | + | + | + |

| Badoo | – | 0% | Medium | NO | – | + | + |

| Mamba | + | 0% | High | High | + | – | + |

| Zoosk | + | 0% | High | High | – (+ iOS) |

– | + |

| Happn | + | 100% | NO | NO | + | + | + |

| + | 0% | NO | NO | – | – | – | |

| Paktor | + | 100% emails | Medium | NO | + | + | + |

Location — determining user location (“+” – possible, “-” not possible)

Stalking — finding the full name of the user, as well as their accounts in other social networks, the percentage of detected users (percentage indicates the number of successful identifications)

HTTP — the ability to intercept any data from the application sent in an unencrypted form (“NO” – could not find the data, “Low” – non-dangerous data, “Medium” – data that can be dangerous, “High” – intercepted data that can be used to get account management).

HTTPS — interception of data transmitted inside the encrypted connection (“+” – possible, “-” not possible).

Messages — access to user messages by using root rights (“+” – possible, “-” not possible).

TOKEN — possibility to steal authentication token by using root rights (“+” – possible, “-” not possible).

As you can see from the table, some apps practically do not protect users’ personal information. However, overall, things could be worse, even with the proviso that in practice we didn’t study too closely the possibility of locating specific users of the services. Of course, we are not going to discourage people from using dating apps, but we would like to give some recommendations on how to use them more safely. First, our universal advice is to avoid public Wi-Fi access points, especially those that are not protected by a password, use a VPN, and install a security solution on your smartphone that can detect malware. These are all very relevant for the situation in question and help prevent the theft of personal information. Secondly, do not specify your place of work, or any other information that could identify you. Safe dating!

Dangerous liaisons

Fernando Ardenghi

Perhaps many of those dating apps are not interested at all in security.

Moreover, they could be involved with a mafia of white hat hackers in the spyware business.

Badoo is in big war with Tinder (Match Group). When Match Group (fka IAC Personals) bought OKCupid (6+ years ago) for an astronomical amount of money, the OKCupid team had the task to copycat Badoo, but they failed in that mission.

IAC / Match Group “acquired” HatchLabs to “develop” Tinder copycat of Badoo.

Then Badoo backed Bumble to fight back and destroy Tinder (last December 2014).

Regards, Fernando.

Robert

It’s a useful article. So when there in NO in the comparison table for HTTP, does it mean that messages cannot be read on a public network by anyone else?