The first member of the Proton malware family?

An interesting aspect of studying a particular piece of malware is tracing its evolution and observing how the creators gradually add new monetization or entrenchment techniques. Also of interest are developmental prototypes that have had limited distribution or not even occurred in the wild. We recently came across one such sample: a macOS backdoor that we named Calisto.

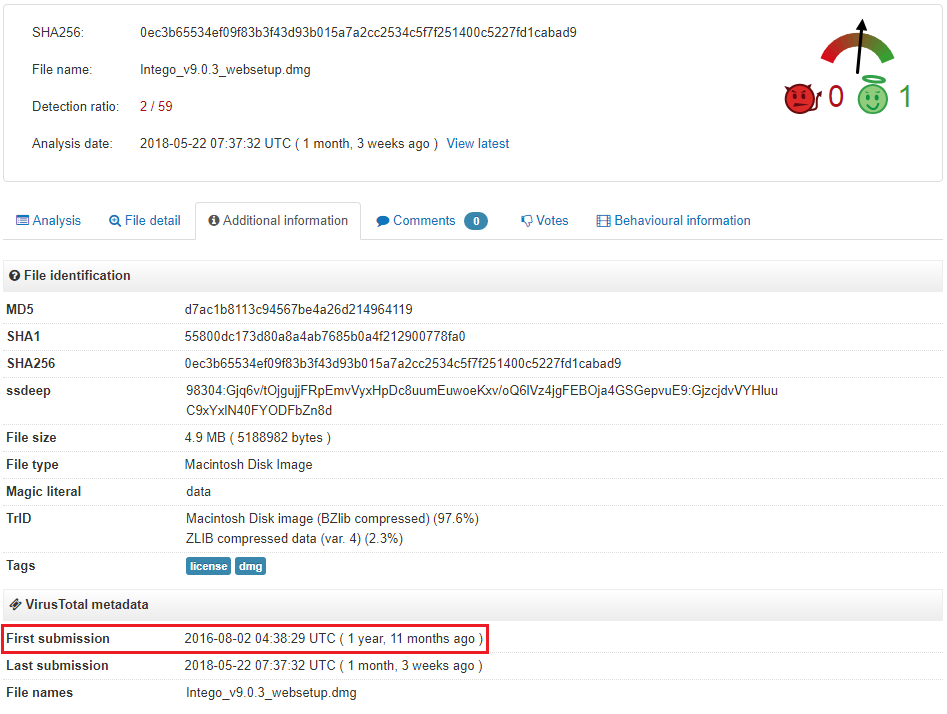

The malware was uploaded to VirusTotal way back in 2016, most likely the same year it was created. But for two whole years, until May 2018, Calisto remained off the radar of antivirus solutions, with the first detections on VT appearing only recently.

Malware for macOS is not that common, and this sample was found to contain some suspiciously familiar features. So we decided to unpick Calisto to see what it is and why its development was stopped (or was it?).

Propagation

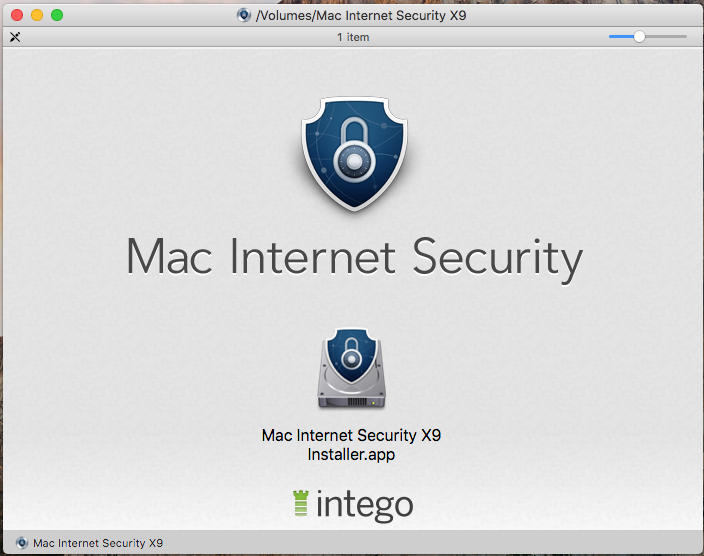

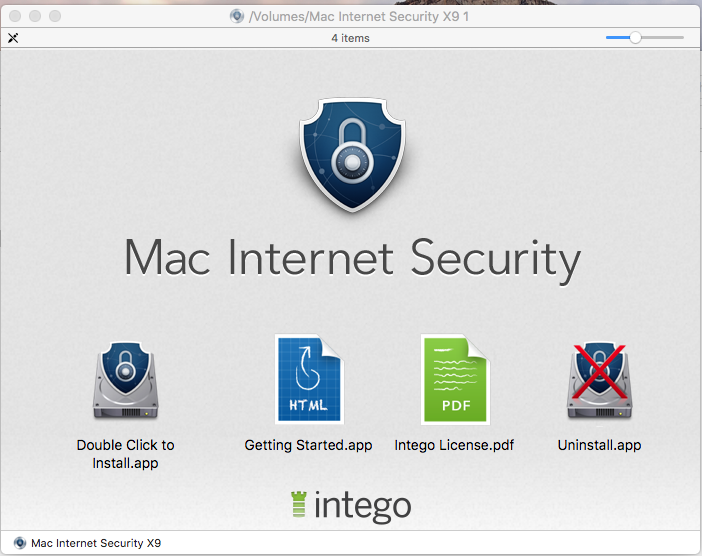

We have no reliable information about how the backdoor was distributed. The Calisto installation file is an unsigned DMG image under the guise of Intego’s security solution for Mac. Interestingly, Calisto’s authors chose the ninth version of the program as a cover which is still relevant.

For illustrative purposes, let’s compare the malware file with the version of Mac Internet Security X9 downloaded from the official site.

| Backdoor | Intego Mac Internet Security 2018 |

| Unsigned | Signed by Intego |

|

|

|

|

It looks fairly convincing. The user is unlikely to notice the difference, especially if he has not used the app before.

Installation

As soon as it starts, the application presents us with a sham license agreement. The text differs slightly from the Intego’s one — perhaps the cybercriminals took it from an earlier version of the product.

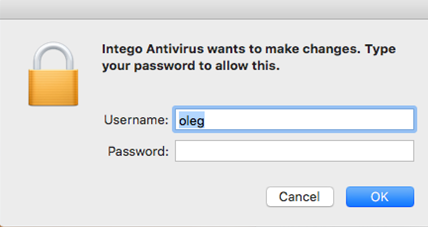

Next, the “antivirus” asks for the user’s login and password, which is completely normal when installing a program able to make changes to the system on macOS.

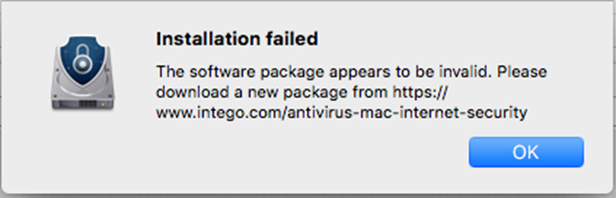

But after receiving the credentials, the program hangs slightly before reporting that an error has occurred and advising the user to download a new installation package from the official site of the antivirus developer.

The technique is simple, but effective. The official version of the program will likely be installed with no problems, and the error will soon be forgotten. Meanwhile, in the background, Calisto will be calmly getting on with its mission.

Analysis of the Trojan

With SIP enabled

Calisto’s activity on a computer with SIP (System Integrity Protection) enabled is rather limited. Announced by Apple back in 2015 alongside the release of OSX El Capitan, SIP is designed to protect critical system files from being modified — even by a user with root permissions. Calisto was developed in 2016 or earlier, and it seems that its creators simply didn’t take into account the then-new technology. However, many users still disable SIP for various reasons; we categorically advise against doing so.

Calisto’s activity can be investigated using its child processes log and decompiled code:

We can see that the Trojan uses a hidden directory named .calisto to store:

- Keychain storage data

- Data extracted from the user login/password window

- Information about the network connection

- Data from Google Chrome: history, bookmarks, cookies

Recall that Keychain stores passwords/tokens saved by the user, including ones saved in Safari. The encryption key for the storage is the user’s password.

Next, if SIP is enabled, an error occurs when the Trojan attempts to modify system files. This violates the operational logic of the Trojan, causing it to stop.

With SIP disabled/not available

Observing Calisto with SIP disabled is far more interesting. To begin with, Calisto executes the steps from the previous chapter, but as the Trojan is not interrupted by SIP, it then:

- Copies itself to /System/Library/ folder

- Sets itself to launch automatically on startup

- Unmounts and uninstalls its DMG image

- Adds itself to Accessibility

- Harvests additional information about the system

- Enables remote access to the system

- Forwards the harvested data to a C&C server

Let’s take a closer look at the malware’s implementation mechanisms.

Adding itself to startup is a classic technique for macOS, and is done by creating a .plist file in the /Library/LaunchAgents/ folder with a link to the malware:

The DMG image is unmounted and uninstalled via the following command:

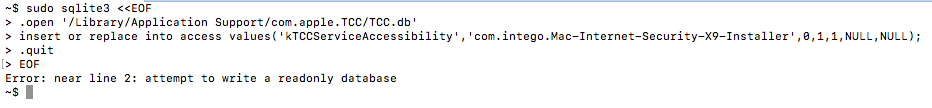

To extend its capabilities, Calisto adds itself to Accessibility by directly modifying the TCC.db file, which is bad practice and an indicator of malicious activity for the antivirus. On the other hand, this method does not require user interaction.

An important feature of Calisto is getting remote access to the user system. To provide this, it:

- Enables remote login

- Enables screen sharing

- Configures remote login permissions for the user

- Allows remote login to all

- Enables a hidden “root” account in macOS and sets the password specified in the Trojan code

The commands used for this are:

Note that although the user “root” exists in macOS, it is disabled by default. Interestingly, after a reboot, Calisto again requests user data, but this time waits for the input of the actual root password, which it previously changed itself (root: aGNOStIC7890!!!). This is one indication of the Trojan’s rawness.

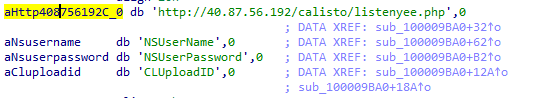

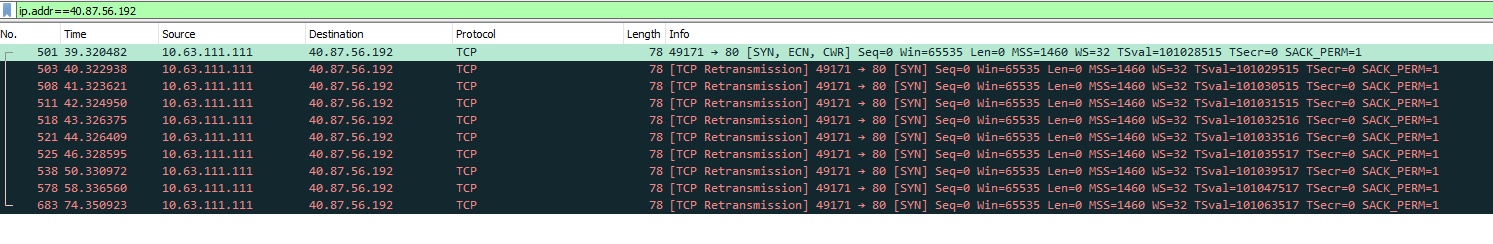

At the end, Calisto attempts to transfer all data from the .calisto folder to the cybercriminals’ server. But at the time of our research, the server was no longer responding to requests and seemed to be disabled:

Extra functions

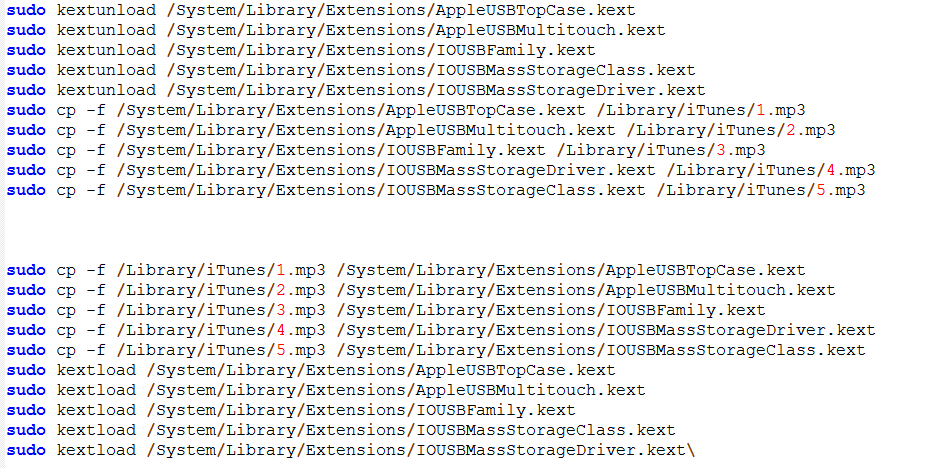

Static analysis of Calisto revealed unfinished and unused additional functionality:

- Loading/unloading of kernel extensions for handling USB devices

- Data theft from user directories

- Self-destruction together with the OS

Connections with Backdoor.OSX.Proton

Conceptually, the Calisto backdoor resembles a member of the Backdoor.OSX.Proton family:

- The distribution method is similar: it masquerades as a well-known antivirus (a Backdoor.OSX.Proton was previously distributed under the guise of a Symantec antivirus product)

- The Trojan sample contains the line “com.proton.calisto.plist”

- Like Backdoor.OSX.Proton, this Trojan is able to steal a great amount of personal data from the user system, including the contents of Keychain

Recall that all known members of the Proton malware family were distributed and discovered in 2017. The Calisto Trojan we detected was created no later than 2016. Assuming that this Trojan was written by the same authors, it could well be one of the very first versions of Backdoor.OSX.Proton or even a prototype. The latter hypothesis is supported by the large number of unused and not fully implemented functions. However, they were missing from later versions of Proton.

To protect against Calisto, Proton, and their analogues:

- Always update to the current version of the OS

- Never disable SIP

- Run only signed software downloaded from trusted sources, such as the App Store

- Use antivirus software

MD5

DMG image: d7ac1b8113c94567be4a26d214964119

Mach-O executable: 2f38b201f6b368d587323a1bec516e5d

Calisto Trojan for macOS