We may only be six months in, but there’s little doubt that 2020 will go down in history as a rather unpleasant year. In the field of cybersecurity, the collective hurt mostly crystallized around the increasing prevalence of targeted ransomware attacks. By investigating a number of these incidents and through discussions with some of our trusted industry partners, we feel that we now have a good grasp on how the ransomware ecosystem is structured.

Structure of the ransomware ecosystem

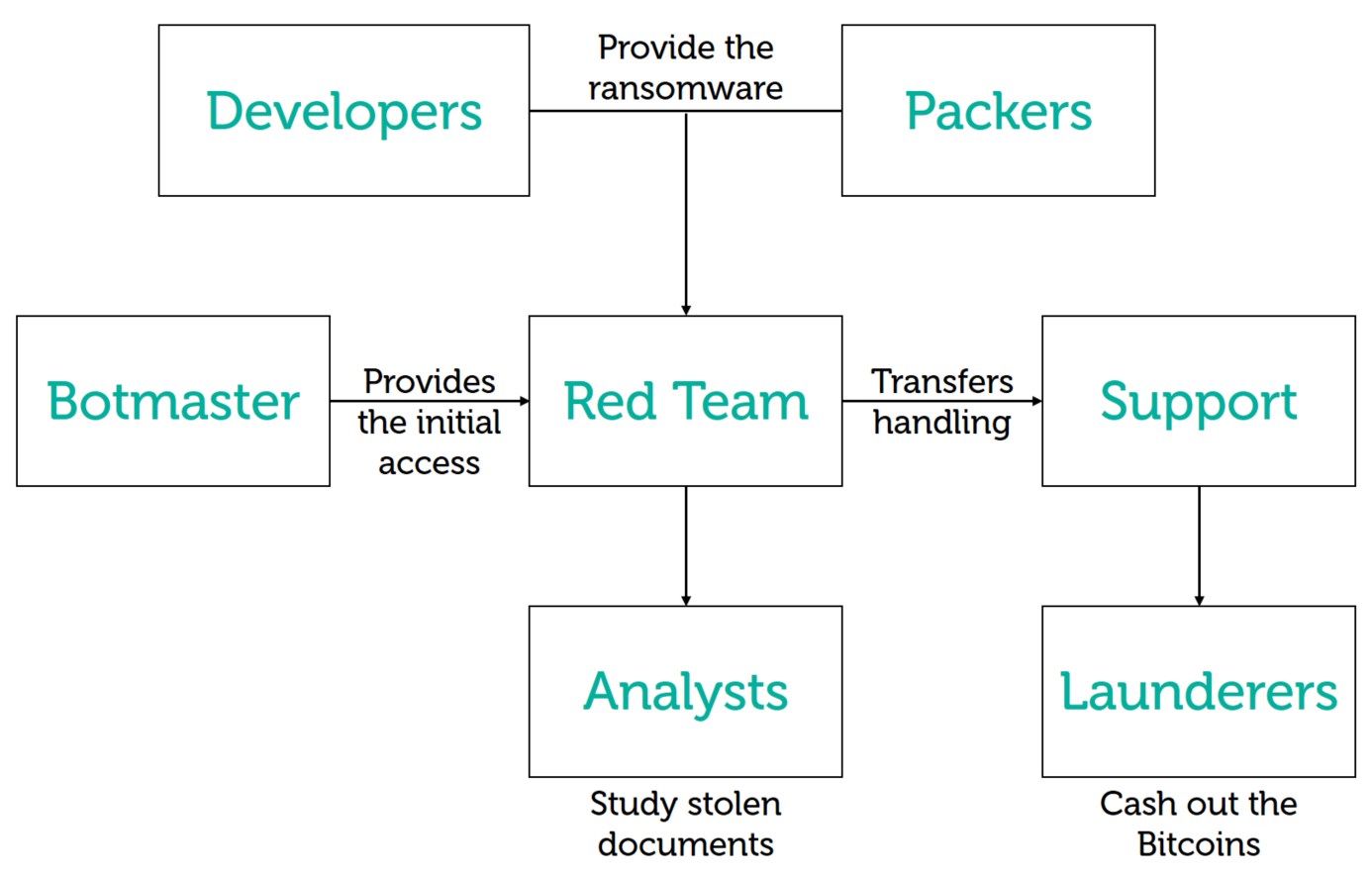

Criminals piggyback on widespread botnet infections (for instance, the infamous Emotet and Trickbot malware families) to spread into the network of promising victims and license ransomware “products” from third-party developers. When the attackers have a good understanding of the target’s finances and IT processes, they deploy the ransomware on all the company’s assets and enter the negotiation phase.

This ecosystem operates in independent, highly specialized clusters, which in most cases have no links to each other beyond their business ties. This is why the concept of threat actors gets fuzzy: the group responsible for the initial breach is unlikely to be the party that compromised the victim’s Active Directory server, which in turn is not the one that wrote the actual ransomware code used during the incident. What’s more, over the course of two incidents, the same criminals may switch business partners and could be leveraging different botnet and/or ransomware families altogether.

But of course, no complex ecosystem could ever be described by a single, rigid set of rules and this one is no exception. In this blog post, we describe one of these outliers over two separate investigations that occurred between March and May 2020.

Case #1: The VHD ransomware

This first incident occurred in Europe and caught our attention for two reasons: it features a ransomware family we were unaware of, and involved a spreading technique reminiscent of APT groups (see the “spreading utility” details below). The ransomware itself is nothing special: it’s written in C++ and crawls all connected disks to encrypt files and delete any folder called “System Volume Information” (which are linked to Windows’ restore point feature). The program also stops processes that could be locking important files, such as Microsoft Exchange and SQL Server. Files are encrypted with a combination of AES-256 in ECB mode and RSA-2048. In our initial report published at the time we noted two peculiarities with this program’s implementation:

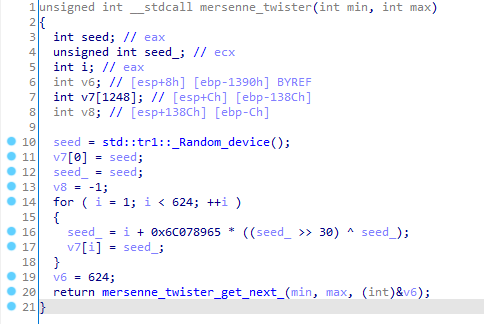

- The ransomware uses Mersenne Twister as a source of randomness, but unfortunately for the victims the RNG is reseeded every time new data is consumed. Still, this is unorthodox cryptography, as is the decision to use the “electronic codebook” (ECB) mode for the AES algorithm. The combination of ECB and AES is not semantically secure, which means the patterns of the original clear data are preserved upon encryption. This was reiterated by cybersecurity researchers who analyzed Zoom security in April 2020.

- VHD implements a mechanism to resume operations if the encryption process is interrupted. For files larger than 16MB, the ransomware stores the current cryptographic materials on the hard drive, in clear text. This information is not deleted securely afterwards, which implies there may be a chance to recover some of the files.

The Mersenne Twister RNG is reseeded every time it is called.

To the best of our knowledge, this malware family was first discussed publicly in this blog post.

A spreading utility, discovered along the ransomware, propagated the program inside the network. It contained a list of administrative credentials and IP addresses specific to the victim, and leveraged them to brute-force the SMB service on every discovered machine. Whenever a successful connection was made, a network share was mounted, and the VHD ransomware was copied and executed through WMI calls. This stood out to us as an uncharacteristic technique for cybercrime groups; instead, it reminded us of the APT campaigns Sony SPE, Shamoon and OlympicDestroyer, three previous wipers with worming capabilities.

We were left with more questions than answers. We felt that this attack did not fit the usual modus operandi of known big-game hunting groups. In addition, we were only able to find a very limited number of VHD ransomware samples in our telemetry, and a few public references. This indicated that this ransomware family might not be traded widely on dark market forums, as would usually be the case.

Case #2: Hakuna MATA

A second incident, two months later, was handled by Kaspersky’s Incident Response team (GERT). That meant we were able to get a complete picture of the infection chain leading to the installation of the VHD ransomware.

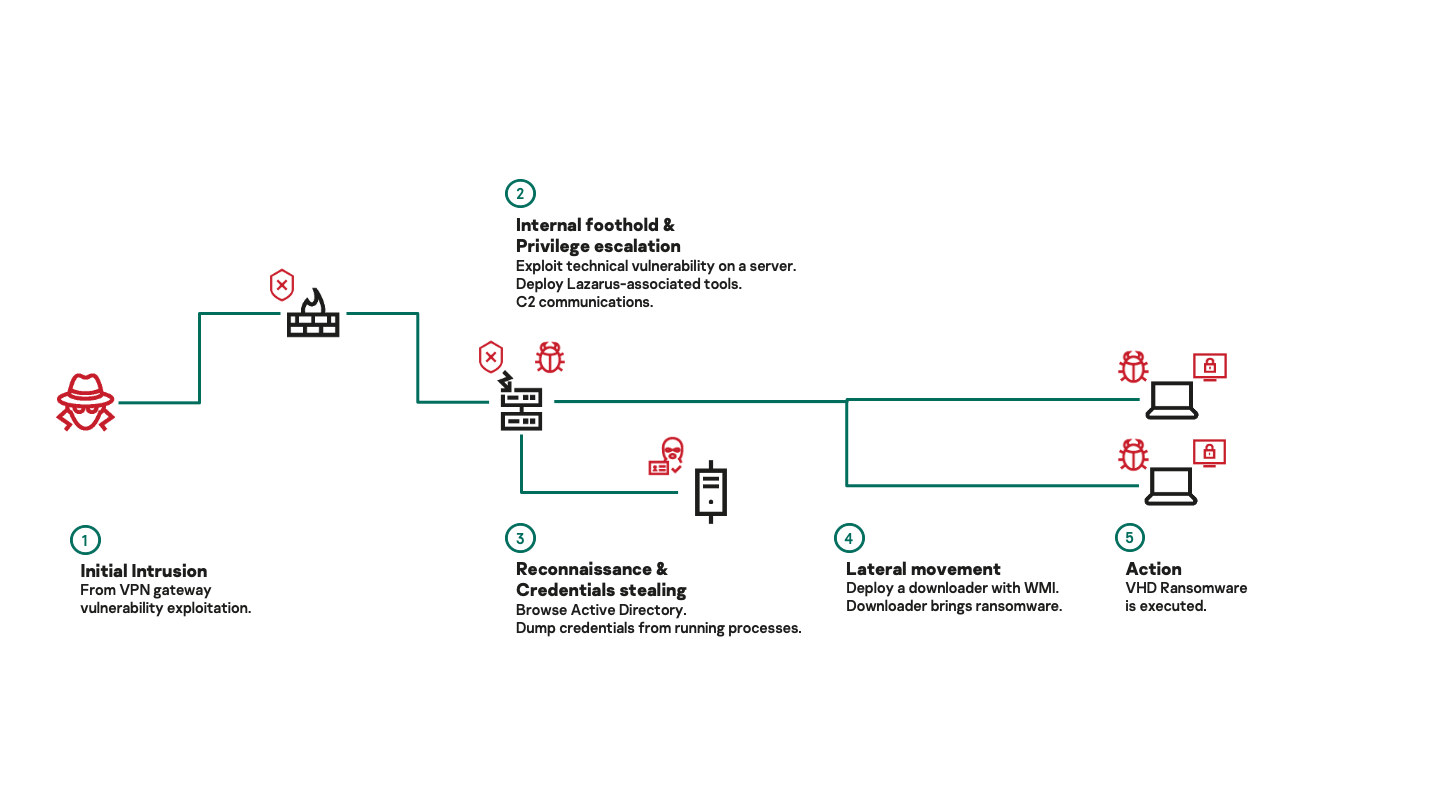

In this instance, we believe initial access was achieved through opportunistic exploitation of a vulnerable VPN gateway. After that, the attackers obtained administrative privileges, deployed a backdoor on the compromised system and were able to take over the Active Directory server. They then deployed the VHD ransomware to all the machines in the network. In this instance, there was no spreading utility, but the ransomware was staged through a downloader written in Python that we still believe to be in development. The whole infection took place over the course of 10 hours.

A more relevant piece of information is that the backdoor used during this incident is an instance of a multiplatform framework we call MATA (some vendors also call it Dacls). On July 22, we published a blog article dedicated to this framework. In it, we provide an in-depth description of its capabilities and provide evidence of its links to the Lazarus group. Other members of the industry independently reached similar conclusions.

The forensics evidence gathered during the incident response process is strong enough that we feel comfortable stating with a high degree of confidence that there was only a single threat actor in the victim’s network during the time of the incident.

Conclusion

The data we have at our disposal tends to indicate that the VHD ransomware is not a commercial off-the-shelf product; and as far as we know, the Lazarus group is the sole owner of the MATA framework. Hence, we conclude that the VHD ransomware is also owned and operated by Lazarus.

Circling back to our introduction, this observation is at odds with what we know about the cybercrime ecosystem. Lazarus has always existed at a special crossroads between APT and financial crime, and there have long been rumors in the threat intelligence community that the group was a client of various botnet services. We can only speculate about the reason why they are now running solo ops: maybe they find it difficult to interact with the cybercrime underworld, or maybe they felt they could no longer afford to share their profits with third parties.

It’s obvious the group cannot match the efficiency of other cybercrime gangs with their hit-and-run approach to targeted ransomware. Could they really set an adequate ransom price for their victim during the 10 hours it took to deploy the ransomware? Were they even able to figure out where the backups were located? In the end, the only thing that matters is whether these operations turned a profit for Lazarus.

Only time will tell whether they jump into hunting big game full time, or scrap it as a failed experiment.

Indicators of compromise

The spreader utility contains a list of administrative credentials and IP addresses specific to the victim, which is why it’s not listed in the IoC section.

As the instance of the MATA framework was extracted from memory, no relevant hashes can be provided for it in the IoC section.

VHD ransomware

6D12547772B57A6DA2B25D2188451983

D0806C9D8BCEA0BD47D80FA004744D7D

DD00A8610BB84B54E99AE8099DB1FC20

CCC6026ACF7EADADA9ADACCAB70CA4D6

EFD4A87E7C5DCBB64B7313A13B4B1012

Domains and IPs

172.93.184[.]62 MATA C2

23.227.199[.]69 MATA C2

104.232.71[.]7 MATA C2

mnmski.cafe24[.]com Staging endpoint for the ransomware (personal web space hosted at a legit web service and used as a redirection to another compromised legit website).

Lazarus on the hunt for big game