During the 2021 edition of the SAS conference, I had the pleasure of delivering a workshop focused on reverse-engineering Go binaries. The goal of the workshop was to share basic knowledge that would allow analysts to immediately start looking into malware written in Go. A YouTube version of the workshop was released around the same time. Of course, the drawback of providing entry-level or immediately actionable information is that a few subtleties must be omitted. One particular topic I brushed aside was related to the way that Go creates objects.

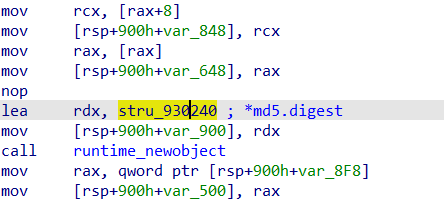

In this screenshot taken from IDA Pro, we can see a call to the runtime.newobject function, which receives a structure as an argument (here, in the RDX register, two lines above the call). The malware presented in the workshop (Sunshuttle, from the DarkHalo APT, MD5 5DB340A70CB5D90601516DB89E629E43) is straightforward to the extent that it can be understood without paying too much attention to these objects. In the videos, I recommend ignoring these calls and instead focusing on documented Golang API functions. With the help of a debugger, it is easy to obtain the arguments and mentally reconstruct the original source code of the application.

However, Go malware following different coding practices could be littered with this kind of objects, to a point where the reverse engineer has no choice but to understand their nature to figure out what the code is supposed to do. Unfortunately, the contents of the structure passed as an argument to runtime.newobject does not immediately appear to contain useful information:

To find out more about this structure, we need to have a look at the Go source code to find the definition for the rtype structure. At the time of writing, its definition for the latest version of Go is as shown below.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 |

type rtype struct { size uintptr ptrdata uintptr // number of bytes in the type that can contain pointers hash uint32 // hash of type; avoids computation in hash tables tflag tflag // extra type information flags align uint8 // alignment of variable with this type fieldAlign uint8 // alignment of struct field with this type kind uint8 // enumeration for C // function for comparing objects of this type // (ptr to object A, ptr to object B) -> ==? equal func(unsafe.Pointer, unsafe.Pointer) bool gcdata *byte // garbage collection data str nameOff // string form ptrToThis typeOff // type for pointer to this type, may be zero } |

There are two fields in this structure that are relevant to us. The first one is “kind”, which is an enum (defined in the same file) representing a sort of base type for the object: Boolean, integers of various lengths, but also arrays, maps, interfaces, etc. The other is “nameOff”, which is a pointer to a string representation of the described type for the purposes of reflection. The latter is extremely useful to reverse engineers, as it immediately tells us what the object is. This structure can itself be contained in specialized ones for interfaces, maps, and so on.

Alas, the result of creating these structures in IDA Pro and applying the correct one to the newobject argument is somewhat underwhelming:

Where is our human-readable name? It turns out that the offset provided by nameOff is relative to the .rdata section of the PE in the case of Windows programs – this is something you can confirm with a hex editor.

The offset leads us to another structure, which contains some information about the string, including its size, and finally, the string itself. Initially, the size of the string had a fixed length (2 bytes), but that appears to have changed in Go 1.17 (now varint-encoded). Nonetheless, the coveted information lies here: the object instantiated in our original newobject call was an md5.digest, which we can now look up in the documentation if needed.

Go programs may contain hundreds of these calls, and newobject is not the only function that relies on these rtype structures (i.e. runtime.makechan, runtime.makemap, etc.), so it is obviously impractical to manually look up each type using a hex editor. Enter IDA scripting! It is, in fact, possible to entirely automate this operation by writing a few lines of Python.

The script I use in my daily work has been included in SentinelOne’s recently released AlphaGoLang repository, as step 5 of the process. It performs the following actions:

- Inspect all the calls to functions, such as newobject, and look at their arguments to find rtype

- Apply the structure shown above to those bytes in IDA to make them easier to read.

- Look up the corresponding string representation for the type and add it as a comment wherever it is referred to.

One thing the script struggles with a little is figuring out how the string size is encoded, as I was not able to find an easy way of determining the Go version from a Python script (yet). Should this cause problems, the many comments should allow you to update the script to fit your use case. If you are new to IDA scripting, I would also recommend that you go have a look at the source code, as it is a great example of the many things you can do with the Python API! And if you would like to learn even more on the subject (and more) with detailed video tutorials, please consider signing up for our online reverse-engineering course on the Xtraining platform.

I hope you find the script useful! Feel free to report any bugs or submit fixes and updates on GitHub!

Extracting type information from Go binaries

Jayme Silvestri

Gentlemen……I think the software on a computer is called a programme.

I’m astonished to hear some one reasonably technically capable calling soft ware an “”””app”” (!!!!!)…………….. that is for 16 year olds with toy phones…….

Viz a vai you have a computer programmer……..I haven’t yet heard of computer “”app”” writer??