Targeted attacks and malware campaigns

Operation Parliament

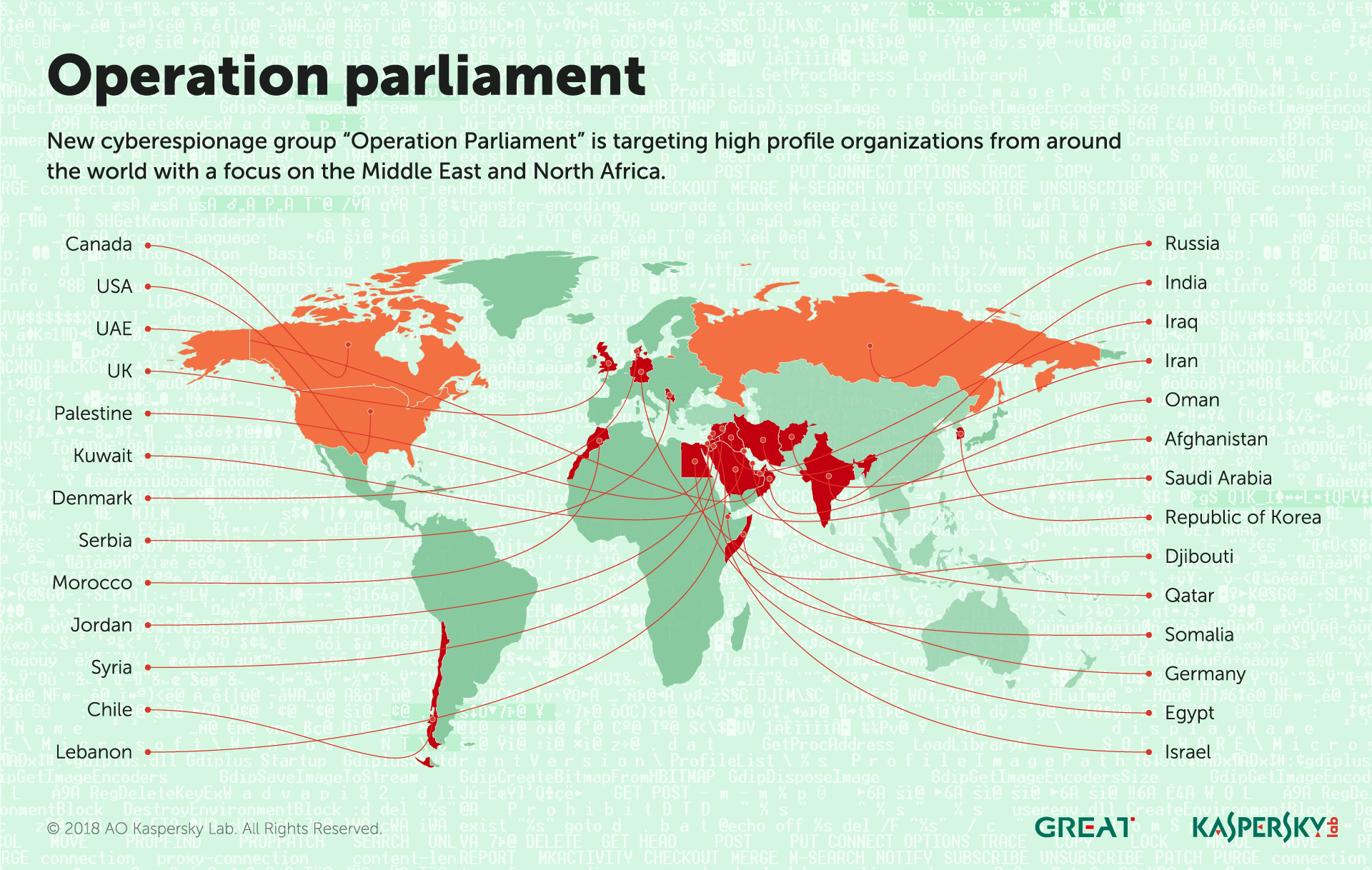

In April, we reported the workings of Operation Parliament, a cyber-espionage campaign aimed at high-profile legislative, executive and judicial organizations around the world – with its main focus in the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region, especially Palestine. The attacks, which started early in 2017, target parliaments, senates, top state offices and officials, political science scholars, military and intelligence agencies, ministries, media outlets, research centers, election commissions, Olympic organizations, large trading companies and others.

The attackers have taken great care to stay under the radar, imitating another attack group in the region. The targeting of victims is unlike that of previous campaigns in the Middle East, by Gaza Cybergang or Desert Falcons, and points to an elaborate information-gathering exercise that was carried out prior to the attacks (physical and/or digital). The attackers have been particularly careful to verify victim devices before proceeding with the infection, safeguarding their C2 (Command-and-Control) servers. The attacks seem to have slowed down since the start of 2018, probably after the attackers achieved their objectives.

The malware basically provides a remote CMD/PowerShell terminal for the attackers, enabling them to execute any scripts or commands and receive the result via HTTP requests.

This campaign is a further symptom of escalating tensions in the Middle East.

Energetic Bear

Crouching Yeti (aka Energetic Bear) is an APT group that has been active since at least 2010, mainly targeting energy and industrial companies. The group targets organizations around the world, but with a particular focus on Europe, the US and Turkey – the latter being a new addition to the group’s interests during 2016-17. The group’s main tactics include sending phishing e-mails with malicious documents and infecting servers for different purposes, including hosting tools and logs and watering-hole attacks. Crouching Yeti’s activities against US targets have been publicly discussed by US-CERT and the UK National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC).

In April, Kaspersky Lab ICS CERT provided information on identified servers infected and used by Crouching Yeti and presented the findings of an analysis of several web servers compromised by the group during 2016 and early 2017.

Our findings are as follows.

- With rare exceptions, the group’s members get by with publicly available tools. The use of publicly available utilities by the group to conduct its attacks renders the task of attack attribution without any additional group ‘markers’ very difficult.

- Potentially, any vulnerable server on the internet is of interest to the attackers when they want to establish a foothold in order to develop further attacks against target facilities.

- In most cases that we have observed, the group performed tasks related to searching for vulnerabilities, gaining persistence on various hosts, and stealing authentication data.

- The diversity of victims may indicate the diversity of the attackers’ interests.

- It can be assumed with some degree of certainty that the group operates in the interests of or takes orders from customers that are external to it, performing initial data collection, the theft of authentication data and gaining persistence on resources that are suitable for the attack’s further development.

You can read the full report here.

ZooPark

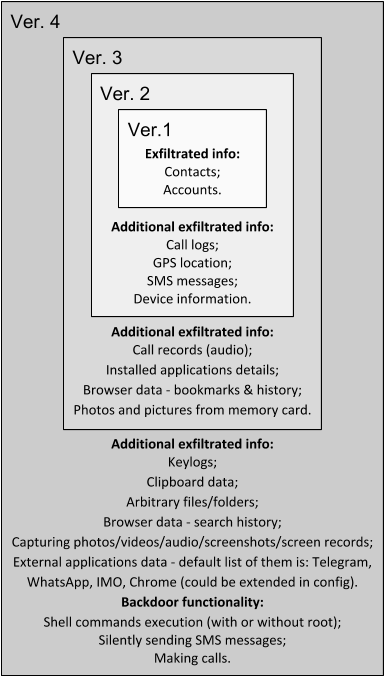

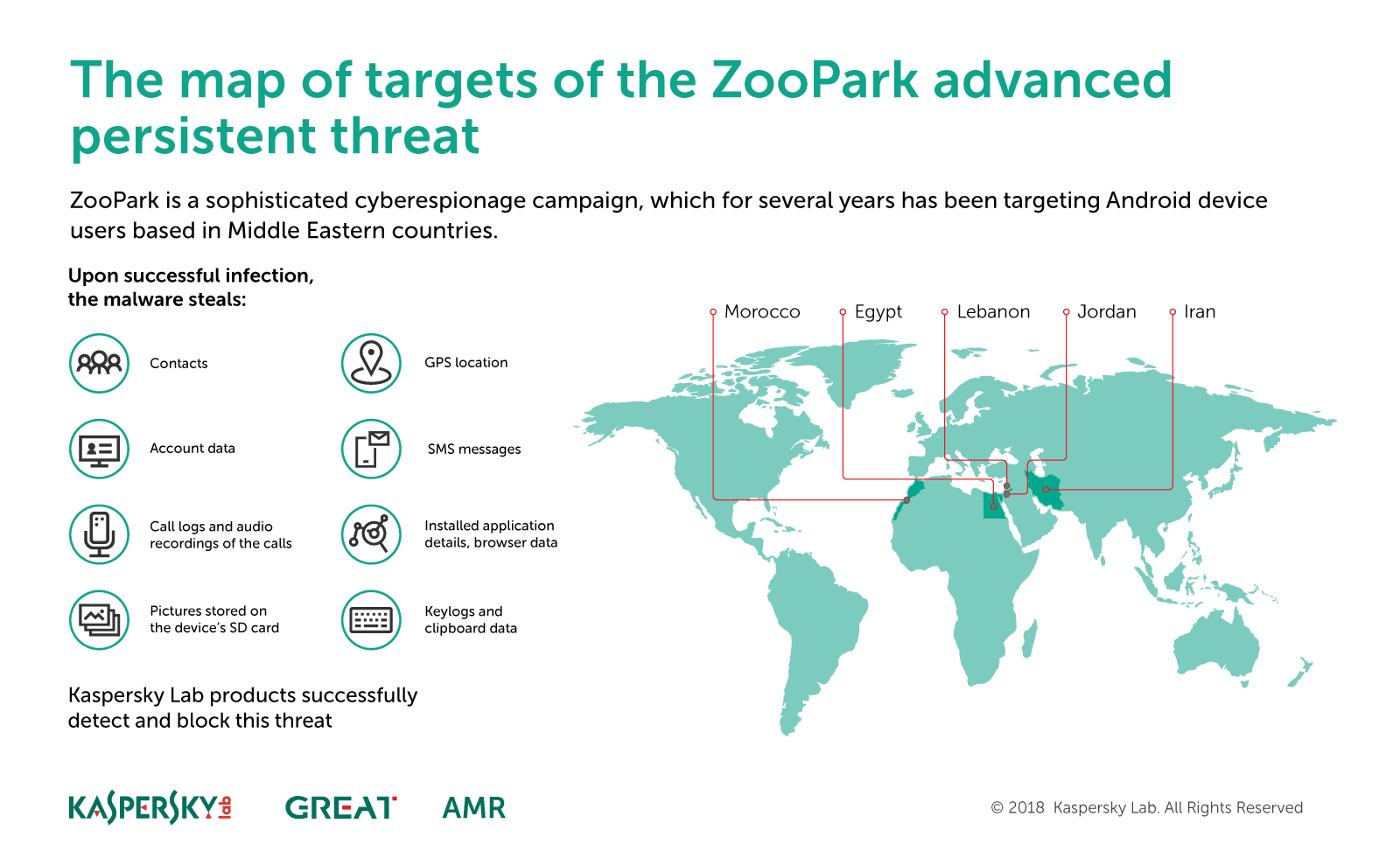

The use of mobile platforms for cyber-espionage has been growing in recent years – not surprising, given the widespread use of mobile devices by businesses and consumers alike. ZooPark is one such operation. The attackers have been focusing on targets in the Middle East since at least June 2015, using several generations of malware to target Android devices, which we have labelled versions one to four.

Each version marks a progression – from very basic first and second versions, to the commercial spyware fork in the third version and then to the complex spyware that is the fourth version. The last step is especially interesting, showing a big leap from straightforward code functionality to highly sophisticated malware.

This suggests that the latest version may have been bought from a vendor of specialist surveillance tools. This wouldn’t be surprising, since the market for these espionage tools is growing, becoming popular among governments, with several known cases in the Middle East. At this point, we cannot confirm attribution to any known threat actor. If you would like to learn more about our intelligence reports, or request more information on a specific report, contact us at intelreports@kaspersky.com.

We have seen two main distribution vectors for ZooPark – Telegram channels and watering-holes. The second of these has been the preferred method: we found several news websites that have been hacked by the attackers to redirect visitors to a downloading site that serves malicious APKs. Some of the themes observed in the campaign include ‘Kurdistan referendum’, ‘TelegramGroups’ and ‘Alnaharegypt news’, among others.

The target profile has evolved in the last few years of the campaign, focusing on victims in Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Lebanon and Iran.

Some of the samples we have analyzed provide clues about the intended targets. For example, one sample mimics a voting application for the independence referendum in Kurdistan. Other possible high-profile targets include the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) for Palestine refugees in the Near East in Amman, Jordan.

The king is dead, long live the king!

On April 18, someone uploaded an interesting exploit to VirusTotal. This was detected by several security vendors, including Kaspersky Lab – using our generic heuristic logic for some older Microsoft Word documents.

This turned out to be a new zero-day vulnerability for Internet Explorer (CVE-2018-8174) –patched by Microsoft on May 8, 2018. Following processing of the sample in our sandbox system, we noticed that it successfully exploited a fully patched version of Microsoft Word. This led us to carry out a deeper analysis of the vulnerability.

The infection chain consists of the following steps. The victim receives a malicious Microsoft Word document. After opening it, the second stage of the exploit is downloaded – an HTML page containing VBScript code. This triggers a UAF (Use After Free) vulnerability and executes shellcode.

Despite the initial attack vector being a Word document, the vulnerability is actually in VBScript. This is the first time we have seen a URL Moniker used to load an IE exploit in Word, but we believe that this technique will be heavily abused by attackers in the future, since it allows them to force victims to load IE, ignoring the default browser settings. It’s likely that exploit kit authors will start abusing it in both drive-by attacks (through the browser) and spear-phishing campaigns (through a document).

To protect against this technique, we would recommend applying the latest security updates and using a security solution with behavior detection capabilities.

VPNFilter

In May, researchers from Cisco Talos published the results of their investigation into VPNFilter, malware used to infect different brands of routers – mainly in Ukraine, although affecting routers in 54 countries in total. Initially, they believed that the malware had infected around 500,000 routers – Linksys, MikroTik, Netgear and TP-Link networking equipment in the small office/home office (SOHO) sector, and QNAP network-attached storage (NAS) devices. However, it later became clear that the list of infected routers was much longer – 75 in total, including ASUS, D-Link, Huawei, Ubiquiti, UPVEL and ZTE.

The malware is capable of bricking the infected device, executing shell commands for further manipulation, creating a TOR configuration for anonymous access to the device or configuring the router’s proxy port and proxy URL to manipulate browsing sessions.

Further research by Cisco Talos showed that the malware is able to infect more than just targeted devices. It is also spread into networks supported by the device, thereby extending the scope of the attack. Researchers also identified a new stage-three module capable of injecting malicious code into web traffic.

The C2 mechanism has several stages. First, the malware tries to visit a number of gallery pages hosted on ‘photobucket[.]com’ and fetches the image from the page. If this fails, the malware tries to fetch an image from the hard-coded domain ‘toknowall[.]com’ (this C2 domain is currently sink-holed by the FBI). If this fails also, the malware goes into passive backdoor mode, in which it processes network traffic on the infected device, waiting for the attacker’s commands. Researchers in the Global Research and Analysis Team (GReAT) at Kaspersky Lab analyzed the EXIF processing mechanism.

One of the interesting questions is who is behind this malware. Cisco Talos indicated that a state-sponsored or state affiliated threat actor is responsible. In its affidavit for sink-holing the C2, the FBI suggests that Sofacy (aka APT28, Pawn Storm, Sednit, STRONTIUM, and Tsar Team) is the culprit. There is some code overlap with the BlackEnergy malware used in previous attacks in Ukraine (the FBI’s affidavit makes it clear that they see BlackEnergy (aka Sandworm) as a sub-group of Sofacy).

LuckyMouse

In March 2018, we detected an ongoing campaign targeting a national data center in Central Asia. The choice of target of the campaign, which has been active since autumn 2017, is especially significant – it means that the attackers were able to gain access to a wide range of government resources in one fell swoop. We think they did this by inserting malicious scripts into the country’s official websites in order to conduct watering-hole attacks.

We attribute this campaign to the Chinese-speaking threat actor LuckyMouse (aka EmissaryPanda and APT27) because of the tools and tactics used in the campaign, because the C2 domain, update.iaacstudio[.]com, was previously used by this group and because they have previously targeted government organizations, including those in Central Asia.

The initial infection vector used in the attack against the data centre is unclear. Even where we observed LuckyMouse using weaponized documents with CVE-2017-118822 (Microsoft Office Equation Editor, widely used by Chinese-speaking actors since December 2017), we couldn’t prove that they were related to this particular attack. It’s possible that the attackers used a watering hole to infect data center employees.

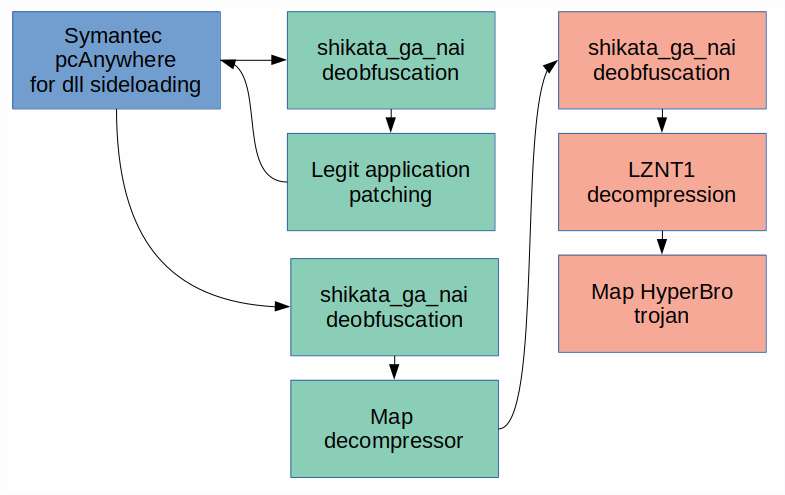

The attackers used the HyperBro Trojan as their last-stage, in-memory remote administration tool (RAT) and their anti-detection launcher and decompressor makes extensive use of the Metasploit ‘shikata_ga_nai’ encoder as well as LZNT1 compression.

The main C2 used in this campaign is bbs.sonypsps[.]com, which resolved to an IP address that belongs to a Ukrainian ISP network, held by a MikroTik router using version 6.34.4 (March 2016) of the firmware with SMBv1 on board. We suspect that this router was hacked as part of the campaign in order to process the malware’s HTTP requests.

The initial module drops three files that are typical for Chinese-speaking threat actors – a legitimate Symantec pcAnywhere file (‘intgstat.exe’) for DLL side-loading, a DLL launcher (‘pcalocalresloader.dll’) and the last-stage decompressor (‘thumb.db’). As a result of all these steps, the last-stage Trojan is injected into the process memory of ‘svchost.exe’.

The launcher module, obfuscated with the notorious Metasploit ‘shikata_ga_nai’ encoder, is the same for all the droppers. The resulting de-obfuscated code performs typical side-loading: it patches the pcAnywhere image in memory at its entry-point. The patched code jumps back to the second ‘shikata_ga_nai’ iteration of the decryptor, but this time as part of the allow-listed application.

The Metasploit encoder obfuscates the last part of the launcher’s code, which in turn resolves the necessary API and maps ‘thumb.db’ into the memory of the same process (i.e. pcAnywhere). The first instructions in the mapped ‘thumb.db’ are for a new iteration of ‘shikata_ga_nai’. The decrypted code resolves the necessary API functions, decompresses the embedded PE file with ‘RtlCompressBuffer()’ using LZNT1 and maps it into memory.

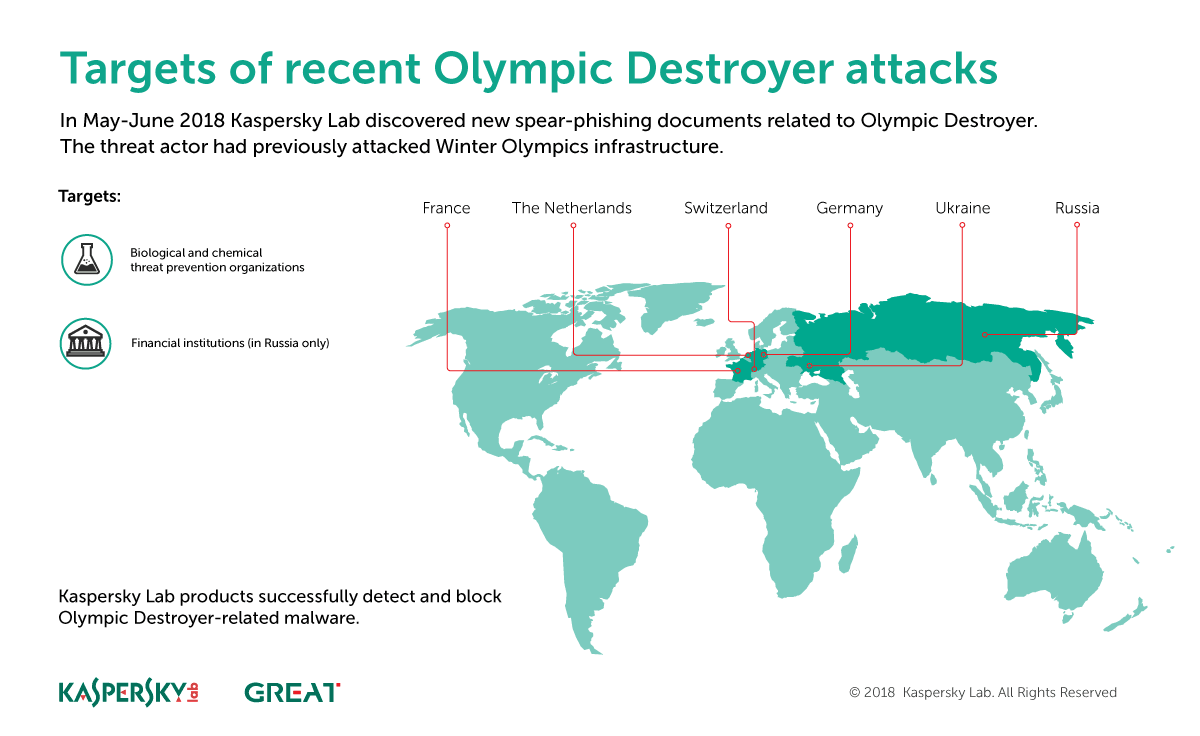

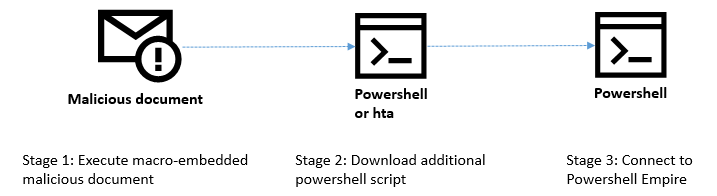

Olympic Destroyer

In our first report on Olympic Destroyer, the cyberattack on the PyeongChang Winter Olympics, we highlighted a specific spear-phishing attack as the initial infection vector. The threat actor sent weaponized documents, disguised as Olympic-related content, to relevant persons and organizations.

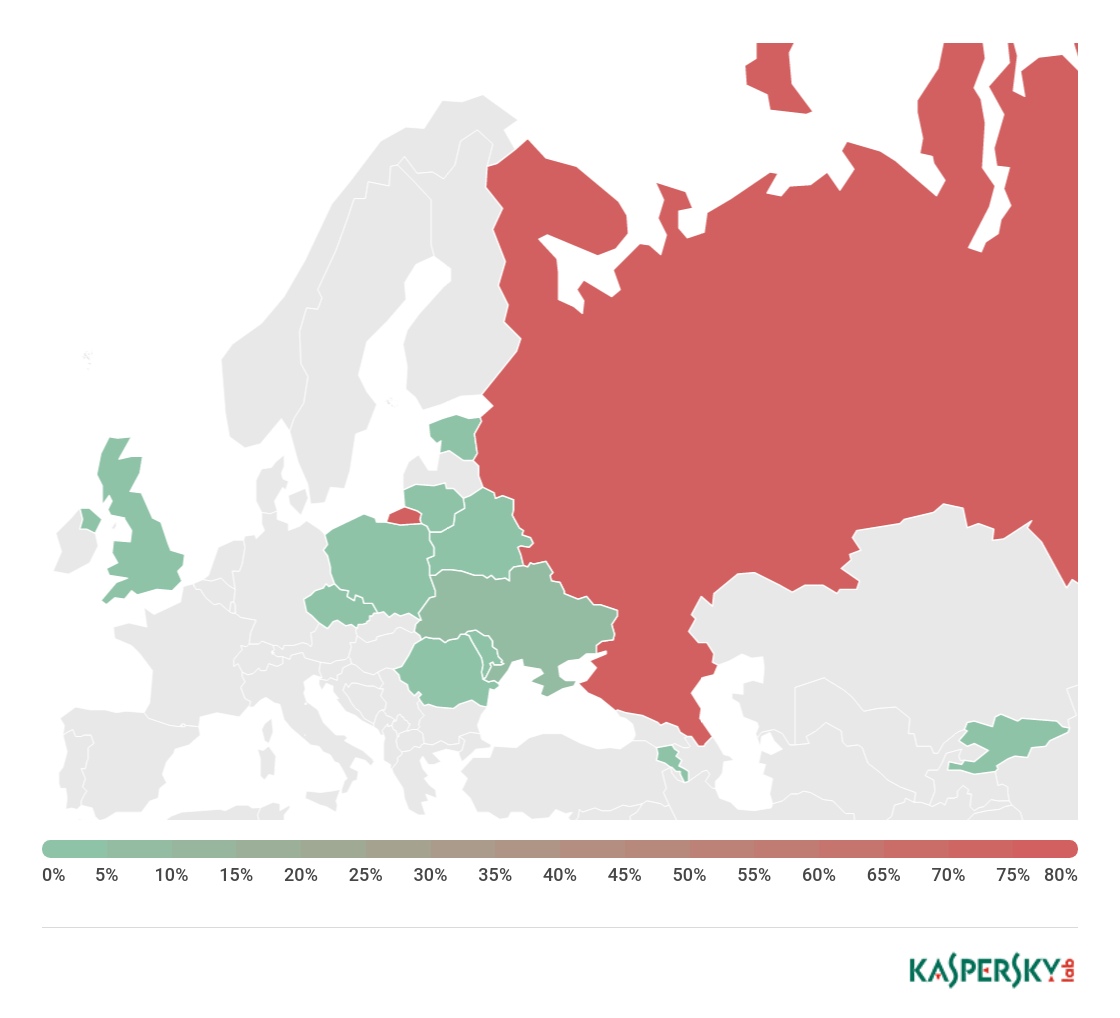

We have continued to track this APT group’s activities and recently noticed that they have started a new campaign with a different geographical distribution and using new themes. Our telemetry, and the characteristics of the spear-phishing documents we have analysed, indicate that the attackers behind Olympic Destroyer are now targeting financial and biotechnology-related organizations based in Europe – specifically, Russia, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland and Ukraine.

The group continues to use a non-executable infection vector and highly obfuscated scripts to evade detection.

The earlier Olympic Destroyer attacks – designed to destroy and paralyse infrastructure of the Winter Olympic Games and related supply chains, partners and venues – were preceded by a reconnaissance operation. It’s possible that the new activities are part of another reconnaissance stage that will be followed by a wave of destructive attacks with new motives. This is why it is important for all bio-chemical threat prevention and research companies and organizations in Europe to strengthen their security and run unscheduled security audits.

The variety of financial and non-financial targets could indicate that the same malware is being used by several groups with different interests. This could also be a result of cyberattack outsourcing, which is not uncommon among nation state threat actors. However, it’s also possible that the financial targets might be another false flag operation by a threat actor that has already shown that they excel at this during their last campaign.

It would be possible to draw certain conclusions about who is behind this campaign, based on the motives and selection of targets. However, it would be easy to make a mistake with only the fragments of the picture that are visible to researchers. The appearance of Olympic Destroyer at the start of this year, with its sophisticated deception efforts, changed the attribution game forever. In our view, it is no longer possible to draw conclusions based on a few attribution vectors discovered during a regular investigation. The response to threats such as Olympic Destroyer should be based on co-operation between the private sector and governments across national borders. Unfortunately, the current geo-political situation in the world only boosts the global segmentation of the internet and introduces many obstacles for researchers and investigators. This will encourage APT attackers to continue marching into the protected networks of foreign governments and commercial companies.

Malware stories

Leaking ads

When we download popular apps with good ratings from official app stores, we assume they are safe. This is partially true, because usually these apps have been developed with security in mind and have been reviewed by the app store’s security team. Recently, we looked at 13 million APKs and discovered that around a quarter of them transmit unencrypted data over the internet. This was unexpected, because most apps were using HTTPS to communicate with their servers. But among the HTTPS requests, there were unencrypted requests to third-party servers. Some of these apps were very popular – in some cases they could boast hundreds of millions of downloads. On further inspection, it became clear that the apps were exposing customer data because of third-party SDKs – with advertising SDKs usually to blame. They collect data so that they can show relevant ads, but often fail to protect that data when sending it to their servers.

In most cases the apps were exposing IMEI, IMSI, Android ID, device information (e.g. manufacturer, model, screen resolution, system version and app name). Some apps were also exposing personal information, mostly the customer’s name, age, gender, phone number, e-mail address and even their income.

Information transmitted over HTTP is sent in plain text, allowing almost anyone to read it. Moreover, there are likely to be several ‘transit points’ en route from the app to the third-party server – devices that receive and store information for a certain period of time. Any network equipment, including your home router, could be vulnerable. If hacked, it will give the attackers access to your data. Some of the device information gathered (specifically IMEI and IMSI numbers) is enough to monitor your further actions. The more complete the information, the more of an open book you are to outsiders — from advertisers to fake friends offering malicious files for download. However, data leakage is only part of the problem. It’s also possible for unencrypted information to be substituted. For example, in response to an HTTP request from an app, the server might return a video ad, which cybercriminals can intercept and replace with a malicious version. Or they might simply change the link inside an ad so that it downloads malware.

You can find the research here, including our advice to developers and consumers.

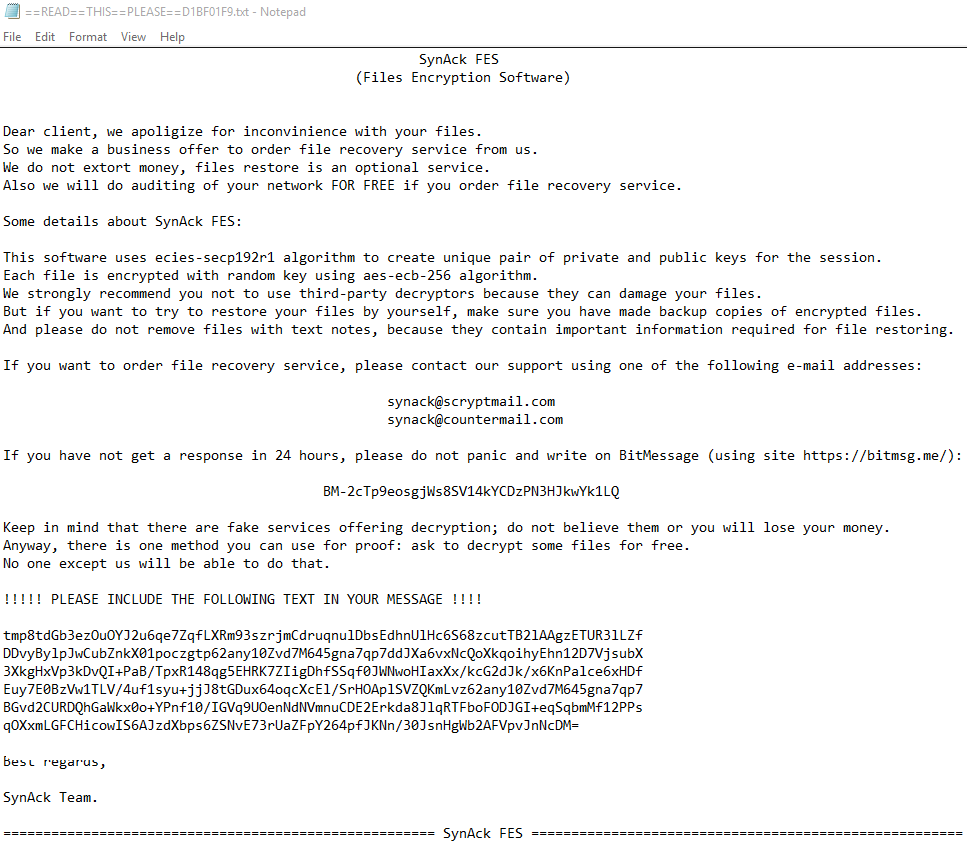

SynAck targeted ransomware uses the Doppelganging technique

In April 2018, we saw a version of the SynAck ransomware Trojan that employs the Process Doppelganging technique. This technique, first presented in December 2017 at the BlackHat conference, has been used by several threat actors to try and bypass modern security solutions. It involves using NTFS transactions to launch a malicious process from the transacted file so that it looks like a legitimate process.

Malware developers often use custom packers to try and protect their code. In most cases, they can be effortlessly packed to reveal the original Trojan executable so that it can then be analyzed. However, the authors of SynAck obfuscated their code prior to compilation, further complicating the analysis process.

SynAck checks the directory where its executable is started from. If an attempt is made to launch it from an ‘incorrect’ directory, the Trojan simply exits. This is designed to counter automatic sandbox analysis.

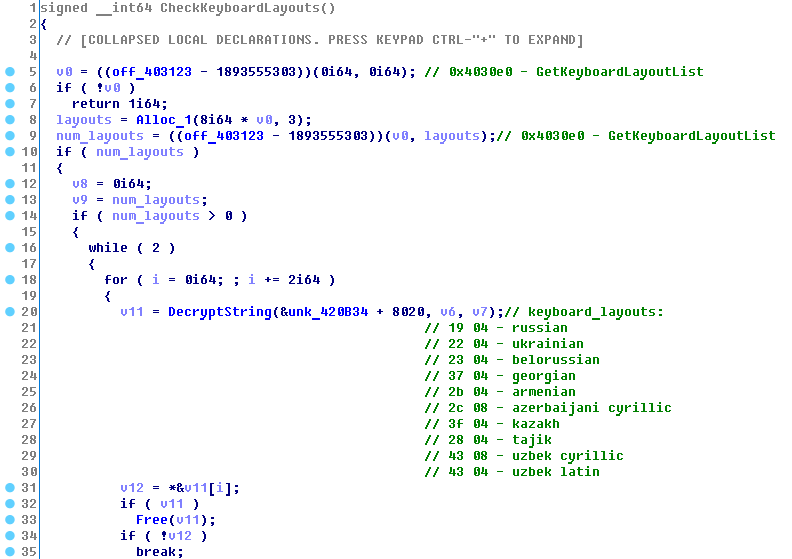

The Trojan also checks to see if is being launched on a PC with the keyboard set to a Cyrillic script. If it is, it sleeps for 300 seconds and then exits, to prevent encryption of files belonging to victims from countries where Cyrillic is used.

Like other ransomware, SynAck uses a combination of symmetric and asymmetric encryption algorithms. You can find the details here.

The attacks are highly targeted, with a limited number of attacks observed against targets in the US, Kuwait, Germany and Iran. The ransom demands can be as high as $3,000.

Roaming Mantis

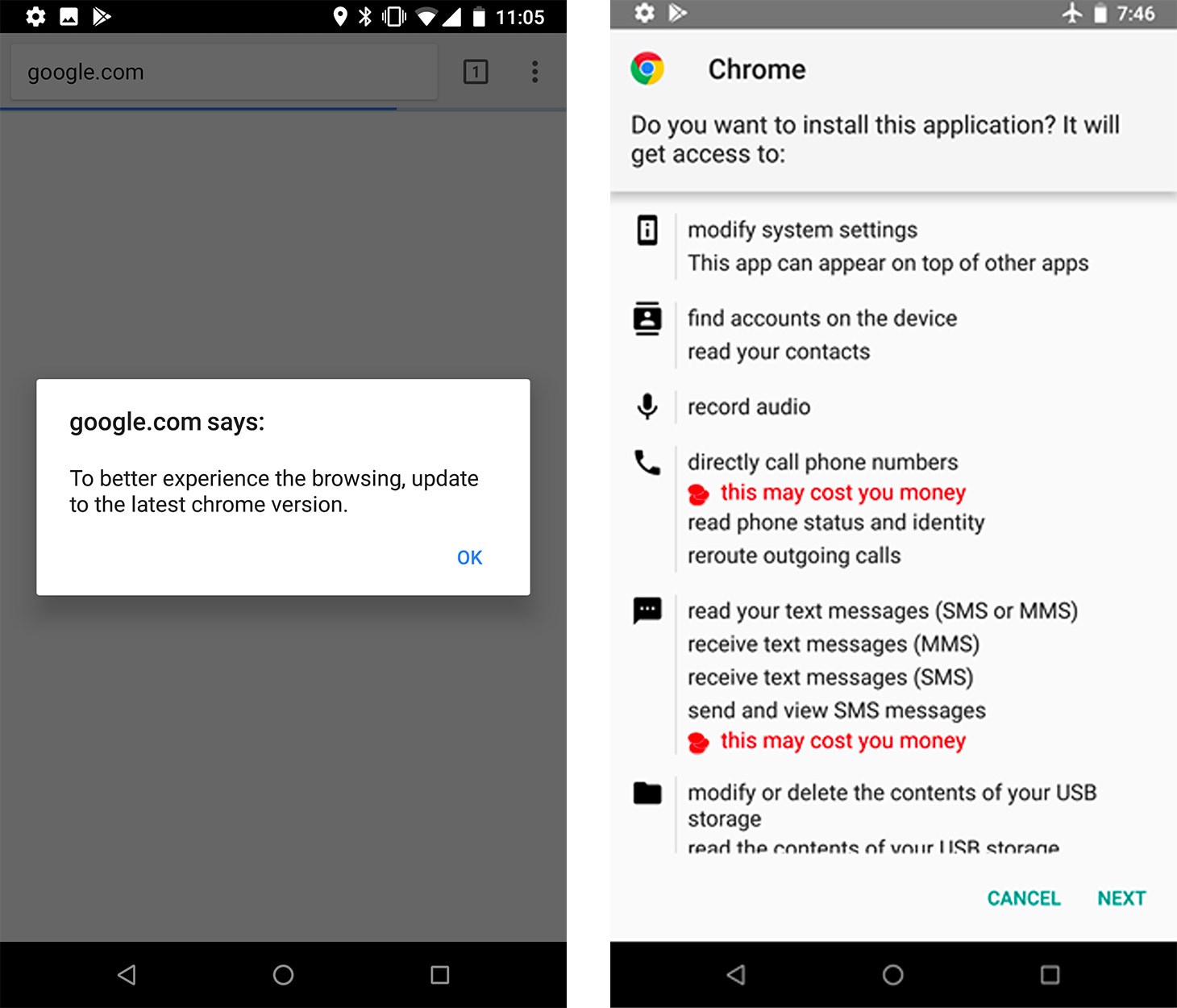

In May we published our analysis of a mobile banking Trojan, Roaming Mantis. We called it this because of its propagation via smartphones roaming between different Wi-Fi networks, although the malware is also known as ‘Moqhao’ and ‘XLoader’. This malicious Android app is spread using DNS hijacking through compromised routers. The victims are redirected to malicious IP addresses used to install malicious apps – called ‘facebook.apk’ and ‘chrome.apk’. The attackers count on the fact that victims are unlikely to be suspicious as long as the browser displays the legitimate URL.

The malware is designed to steal user information, including credentials for two-factor authentication, and give the attackers full control over compromised Android devices. The malware seems to be financially motivated and the low OPSEC suggests that this is the work of cybercriminals.

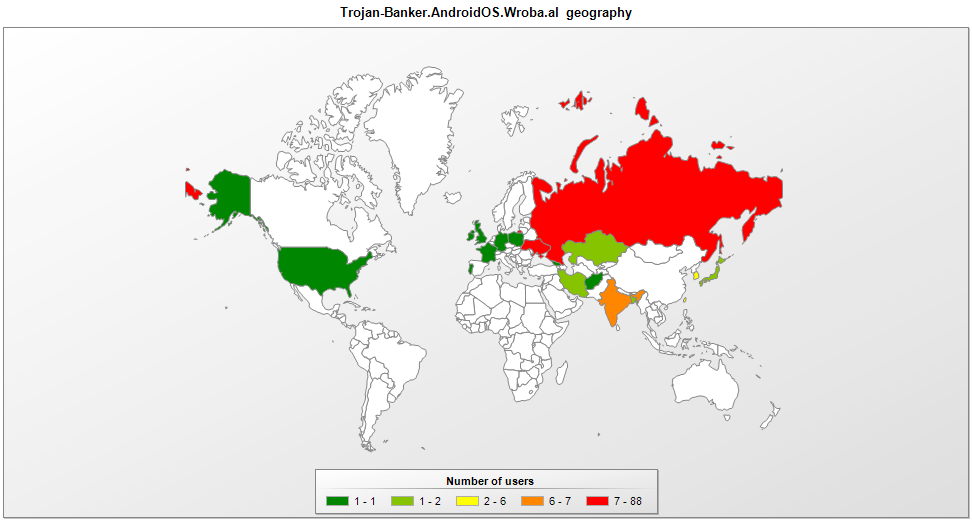

Our telemetry indicates that the malware was detected more than 6,000 times between February 9 and April 9, although the reports came from just 150 unique victims – some of whom saw the same malware appear again and again on their network. Our research revealed that there were thousands of daily connections to the attackers’ C2 infrastructure.

The malware contains Android application IDs for popular mobile banking and game applications in South Korea. It seems the malicious app was initially targeted at victims in South Korea and this is where the malware was most prevalent. We also saw infections in China, India and Bangladesh.

It’s unclear how the attackers were able to hijack the router settings. If you are concerned about DNS settings on your router, you should check the user manual to verify that your DNS settings haven’t been tampered with, or contact your ISP for support. We would also strongly recommend that you change the default login and password for the admin web interface of the router, don’t install firmware from third-party sources and update the router firmware regularly to prevent similar attacks.

Some clues left behind by the attackers – for example, comments in the HTML source, malware strings and a hardcoded legitimate website – point to Simplified Chinese. So we believe the cybercriminals are familiar with both Simplified Chinese and Korean.

Following our report, we continued to track this campaign. Less than a month later, Roaming Mantis had rapidly expanded its activities to include countries in Europe, the Middle East and beyond, supporting 27 languages in total.

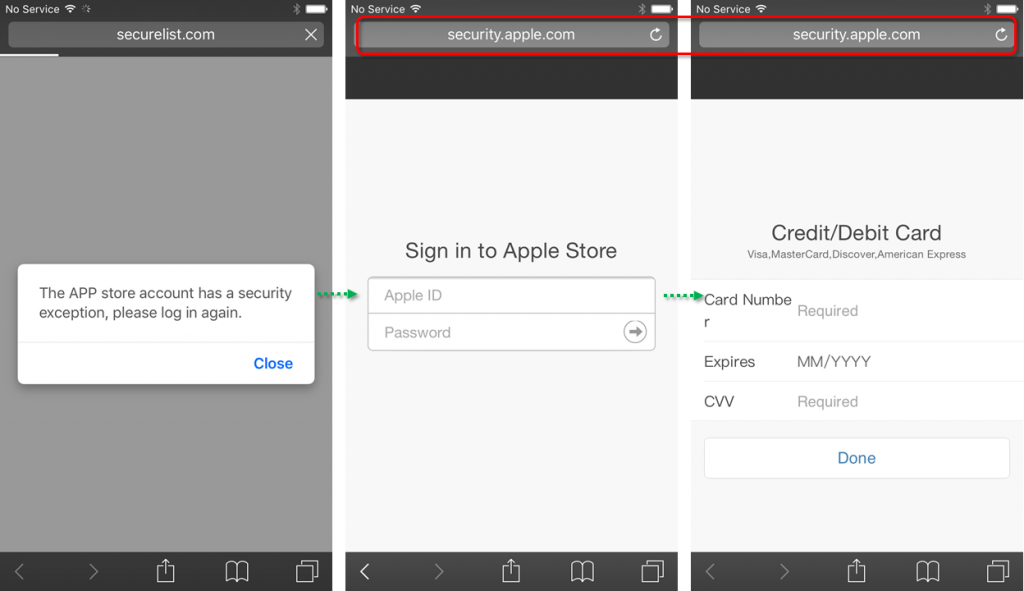

The attackers also extended their activities beyond Android devices. On iOS, Roaming Mantis uses a phishing site to steal the victim’s credentials. When the victim connects to the landing page from an iOS device, they are redirected to fake ‘http://security.apple.com/’ webpage where the attackers steal user ID, password, card number, card expiry date and CVV.

On PCs, Roaming Mantis runs the CoinHive mining script to generate crypto-currency for the attackers – drastically increasing the victim’s CPU usage.

The evasion techniques used by Roaming Mantis have also become more sophisticated. They include a new method of retrieving the C2 by using the e-mail POP protocol, server-side dynamic auto-generation of APK file/filenames and the inclusion of an additional command to potentially assist in identifying research environments.

The rapid growth of the campaign implies that those behind it have a strong financial motivation and are probably well-funded.

If it’s smart, it’s potentially vulnerable

Our many years of experience in researching cyberthreats suggests that if a device is connected to the internet, eventually someone will try to hack it. This includes children’s CCTV cameras, baby monitors, household appliances and even children’s toys.

This also applies to routers – the gateway into a home network. In May, we described four vulnerabilities and hardcoded accounts in the firmware of the D-Link DIR-620 router – this runs on various D-Link routers supplied to customers by one of the biggest ISPs in Russia.

The latest versions of the firmware have hardcoded default credentials that can be exploited by an unauthenticated attacker to gain privileged access to the firmware and to extract sensitive data – for example, configuration files with plain-text passwords. The vulnerable web interface allows an unauthenticated attacker to run arbitrary JavaScript code in the user environment and run arbitrary commands in the router’s operating system. The issues were originally identified in firmware version 1.0.37, although some of the discovered vulnerabilities were also identified in other version of the firmware.

You can read the details on the vulnerabilities here.

In May, we also investigated smart devices for animals – specifically, trackers to monitor the location of pets. These gadgets are able to access the pet owner’s home network and phone, and their pet’s location. We wanted to find out how secure they are. Our researchers looked at several popular trackers for potential vulnerabilities.

Four of the trackers we looked at use Bluetooth LE technology to communicate with the owner’s smartphone. But only one does so correctly. The others can receive and execute commands from anyone. They can also be disabled, or hidden from the owner – all that’s needed is proximity to the tracker. Only one of the tested Android apps verifies the certificate of its server, without relying solely on the system. As a result, they are vulnerable to Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks—intruders can intercept transmitted data by ‘persuading’ victims to install their certificate.

GPS trackers have been used successfully in many areas, but using them to track the location of pets is a step beyond their traditional scope of application. For this, they need to be upgraded with new ‘user communication interfaces’ and ‘trained’ to work with cloud services, etc. If security is not properly addressed, user data becomes accessible to intruders, potentially endangering both users and pets.

Some of our researchers recently looked at human wearable devices – specifically, smart watches and fitness trackers. We were interested in a scenario where a spying app installed on a smartphone could send data from the built-in motion sensors (accelerometer and gyroscope) to a remote server and use the data to piece together the wearer’s actions – walking, sitting, typing, etc. We started with an Android-based smartphone, created a simple app to process and transmit the data and then looked at what we could get from this data.

Not only was it possible to work out if the wearer is sitting or walking, but also figure out if they are out for a stroll or changing subway trains, because the accelerometer patterns differ slightly – this is how fitness trackers distinguish between walking and cycling. It is also easy to see when someone is typing. However, finding out what they are typing would be hard and would require repeated text entry. Our researchers were able to determine the moments when a computer password entered with 96 per cent accuracy and a PIN code entered at an ATM with 87 per cent accuracy. However, it would be much harder to obtain other information – for example, a credit card number or CVC code – because of the lack of predictability about when the victim would type such information.

In reality, the difficulty involved in obtaining such information means that an attacker would have to have a strong motive for targeting someone specific. Of course, there are situations where this might be worthwhile for attackers.

An MitM extension for Chrome

Many browser extensions make our lives easier, hiding obtrusive advertising, translating text, helping us to choose the goods we want in online stores, etc. Unfortunately, there are also less desirable extensions that are used to bombard us with advertising or collect information about our activities. Then there are extensions whose main aim is to steal money. In the course of our work, we analyse a large number of extensions from different sources. Recently, a particular browser extension caught our eye because it communicated with a suspicious domain.

This extension, named ‘Desbloquear Conteúdo’ (which means ‘Unblock Content’ in Portuguese) targeted customers of Brazilian online banking services – all the attempted installations that we traced occurred in Brazil.

The aim of this malicious extension is to harvest logins and passwords and then steal money from the victims’ bank accounts. Such extensions are quite rare, but they need to be taken seriously because of the potential damage they can cause. You should only install verified extensions with large numbers of installations and reviews in the Chrome Web Store or other official service. Even so, in spite of the protection measures implemented by the owners of such services, malicious extensions can still end up being published there. So it’s a good idea to use an internet security product that gives you a warning if an extension acts suspiciously.

By the time we published our report on this malicious extension, it had already been removed from the Chrome Web Store.

The World Cup of fraud

Fraudsters are always on the lookout for opportunities to make money off the back of major sporting events. The FIFA World Cup is no different. Long before anyone kicked a football in Russia, cybercriminals had started to create phishing websites and send messages exploiting World Cup themes.

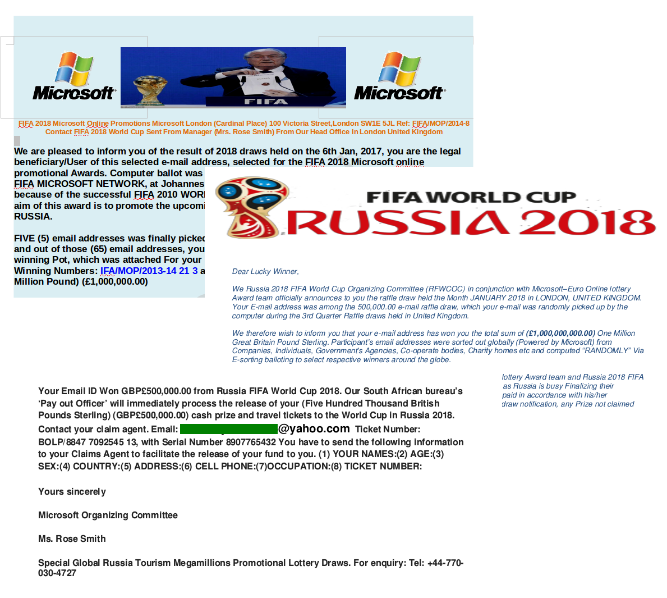

This included notifications of fake lottery wins, informing recipients that they had won cash in a lottery supposedly held by FIFA or official partners and sponsors.

They typically contain attached documents congratulating the ‘winner’ and asking for personal details such as name, address, e-mail address, telephone number, etc. Sometimes such messages also contain malicious programs, such as banking Trojans.

Sometimes recipients are invited to take part in a ticket giveaway, or they are offered the chance to win a trip to a match. Such messages are sent in the name of FIFA, usually from addresses on recently registered domains. The purpose of such schemes is mainly to update e-mail databases used to distribute more spam.

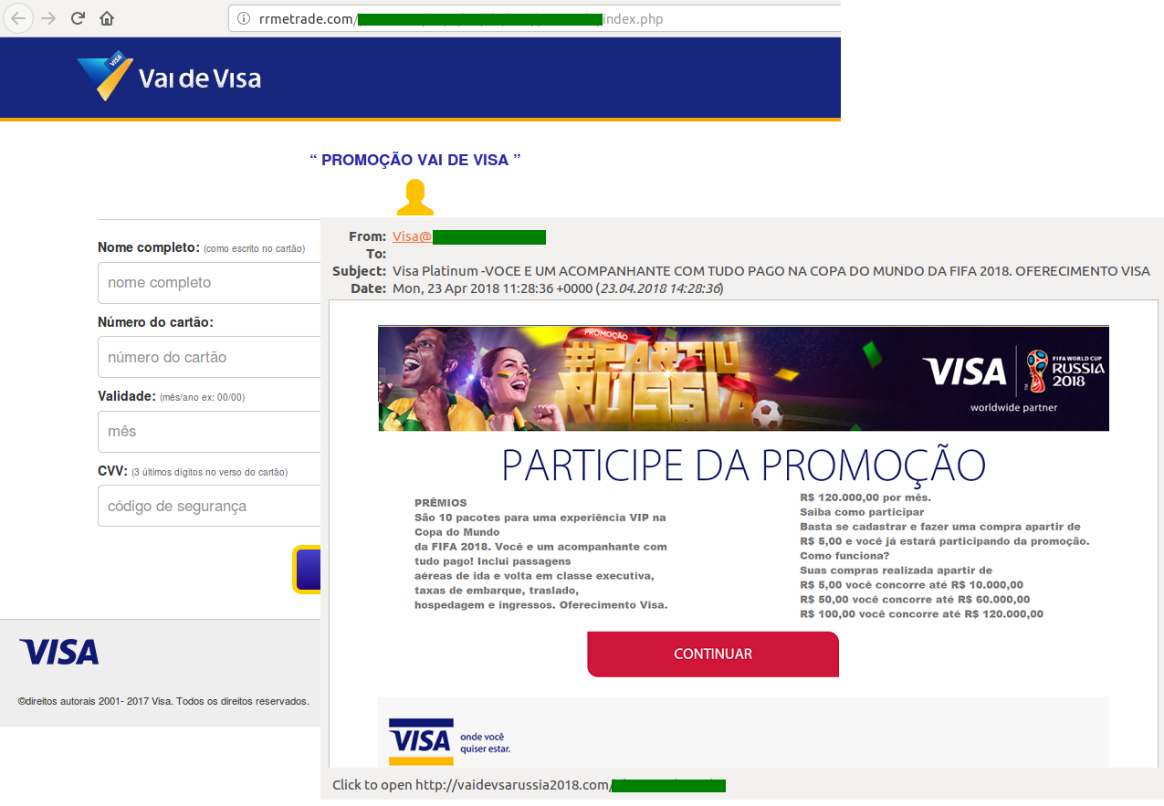

One of the most popular ways to steal banking and other credentials is to create counterfeit imitations of official partner websites. Partner organizations often arrange ticket giveaways for clients, and attackers exploit this to lure their victims onto fake promotion sites. Such pages look very convincing: they are well-designed, with a working interface, and are hard to distinguish from the real thing. Some fraudsters buy SSL certificates to add further credibility to their fake sites. Cybercriminals are particularly keen to target clients of Visa, the tournament’s commercial sponsor, offering prize giveaways in Visa’s name. To take part, people need to follow a link that points to a phishing site where they are asked to enter their bank card details, including the CVV/CVC code.

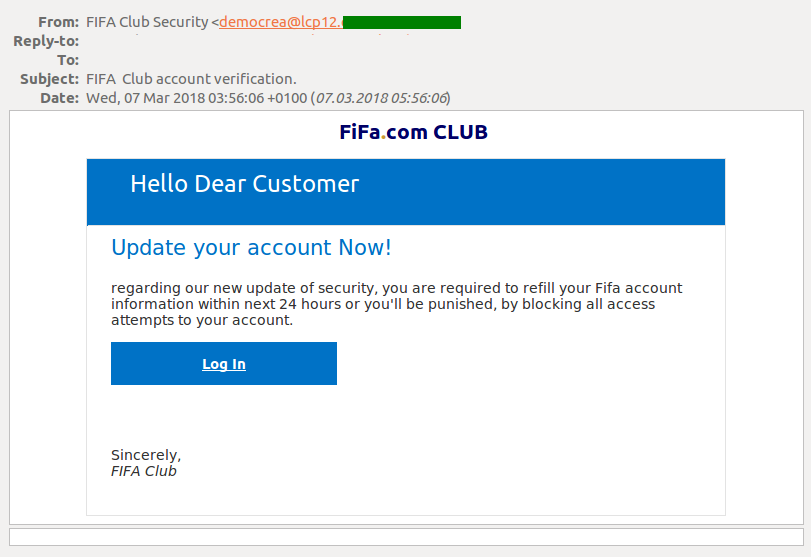

Cybercriminals also try to extract data by mimicking official FIFA notifications. The victim is informed that the security system has been updated and all personal data must be re-entered to avoid being locked out. The link in the message takes the victim to a fake account and all the data they enter is harvested by the scammers.

In the run up to the tournament, we also registered a lot of spam advertising soccer-related merchandise, though sometimes the scammers try to sell other things too – for example, pharmaceutical products.

You can find our report on the ways cybercriminals have exploited the World Cup in order to make money here. We’ve provided some tips on how to avoid phishing scams – advice that holds good for any phishing scams, not just for those related to the World Cup.

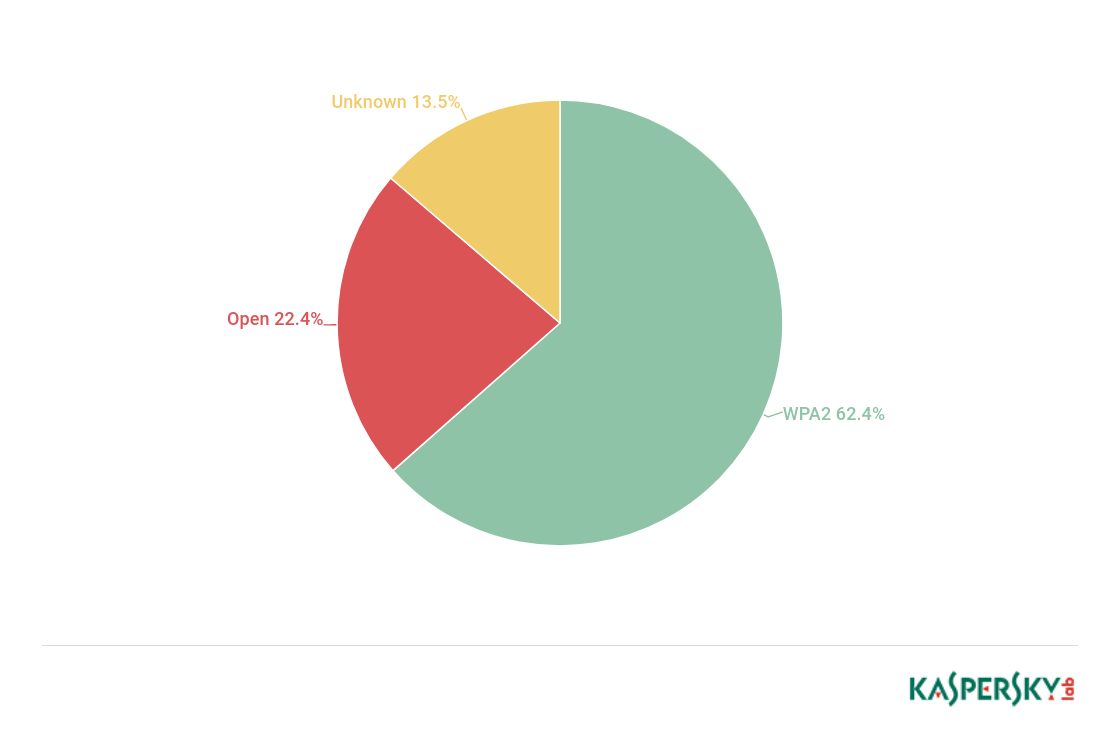

In the run up to the tournament, we also analyzed wireless access points in 11 cities hosting FIFA World Cup matches – nearly 32,000 Wi-Fi hotspots in total. While checking encryption and authentication algorithms, we counted the number of WPA2 and open networks, as well as their share among all the access points.

More than a fifth of Wi-Fi hotspots use unreliable networks. This means that criminals simply need to be located near an access point to intercept the traffic and get their hands on people’s data. Around three quarters of all access points use WPA/WPA2 encryption, considered to be one of the most secure. The level of protection mostly depends on the settings, such as the strength of the password set by the hotspot owner. A complicated encryption key can take years to successfully hack. However, even reliable networks, like WPA2, cannot be automatically considered totally secure. They are still susceptible to brute-force, dictionary and key reinstallation attacks, for which there are a large number of tutorials and open source tools available online. Any attempt to intercept traffic from WPA Wi-Fi in public access points can also be made by penetrating the gap between the access point and the device at the beginning of the session.

You can read our report here, together with our recommendations on the safe use of Wi-Fi hotspots, advice that holds good wherever you may be – not just at the World Cup.

IT threat evolution Q2 2018

Anabell

Around three quarters of all access points use WPA/WPA2 encryption, considered to be one of the most secure