On May 23 2018, our colleagues from Cisco Talos published their excellent analysis of VPNFilter, an IoT / router malware which exhibits some worrying characteristics.

Some of the things which stand out about VPNFilter are:

- It has a redundant, multi-stage command and control mechanism which uses three different channels to receive information

- It has a multi-stage architecture, in which some of the more complex functionality runs only in the memory of the infected devices

- It contains a destructive payload which is capable of rendering the infected devices unbootable

- It uses a broken (or incorrect) RC4 implementation which has been observed before with the BlackEnergy malware

- Stage 2 command and control can be executed over TOR, meaning it will be hard to notice for someone checking the network traffic

We’ve decided to look a bit into the C&C mechanism for the persistent malware payload. As described in the Talos blog, this mechanism has several stages:

- First, the malware tries to visit a number of gallery pages hosted on photobucket[.]com and fetches the first image from the page.

- If this fails, the malware tries fetching an image file from a hardcoded domain, toknowall[.]com. This C2 domain is currently sinkholed by the FBI.

- If that fails as well, the malware goes into a passive backdoor mode, in which it processes network traffic on the infected device waiting for the attacker’s commands.

For the first two scenarios in which the malware successfully receives an image file, a C2 extraction subroutine is called which converts the image EXIF coordinates into an IPv4 address. This is used as an easy way to avoid using DNS lookups to reach the C&C. Of course, in case this fails, the malware will indeed lookup the hardcoded domain (toknowall[.]com). It may be worth pointing that in the past, the BlackEnergy APT devs have shown a preference for using IP addresses for C&C instead of hardcoded domain names, which can be easily sinkholed.

To analyse the EXIF processing mechanism, we looked into the sample 5f358afee76f2a74b1a3443c6012b27b, mentioned in the Talos blog. The sample is an i386 ELF binary and is about 280KB in size.

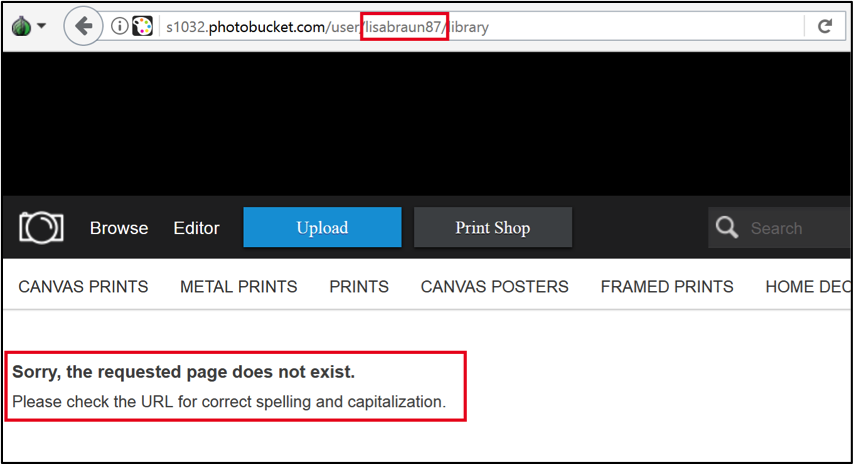

Unfortunately for researchers, it appears that the photobucket.com galleries used by the malware have been deleted, so the malware cannot use the first C2 mechanism anymore. For instance:

With these galleries unavailable, the malware tries to reach the hardcoded domain toknowall[.]com.

While looking at the pDNS history for this domain, we noticed that it resolved to an IP addresses in France, at OVH, between Jan and Feb 2018:

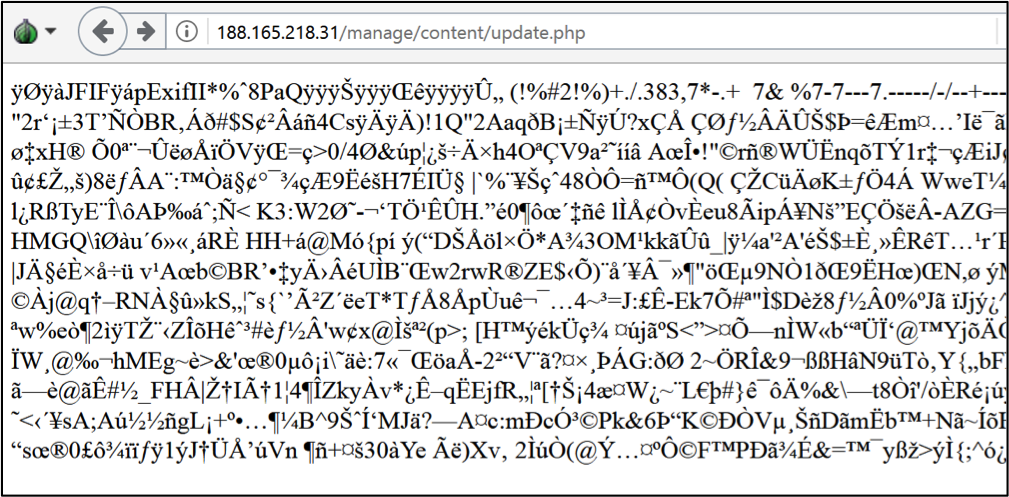

Interestingly, when visiting this website’s C2 URL, we are presented with a JPG image, suggesting it is still an active C2:

Here’s how it looks when viewed as an image:

When we look into the EXIF data for the picture, for instance using IrfanView, it looks as following:

Filename – update.jpg

- GPS information: –

- GPSLatitude – 97 30 -175 (97.451389)

- GPSLongitude – -118 140 -22 (-115.672778)

How to get the IP out of these? The subroutine which calculates the C2 IP from the Latitude and Longitude can be found at offset 0x08049160 in the sample.

As it turns out, VPNFilter implements an actual EXIF parser to get the required information.

First, it searches for a binary value 0xE1. This makes sense because the EXIF attribute information begins with a tag “0xFF 0xE1”. Then, it verifies that the tag is followed by a string “Exif”. This is the exact data that should appear in a correct header of the Exif tag:

Exif tag

FF E1 Exif tag

xx Length of field

45 78 69 66 00 ‘Exif’

00 Padding

The tag is followed by an additional header:

“Attribute information” header

49 49 (or 4D 4D) Byte order, ‘II’ for little endian (‘MM’ for big endian)

2A 00 Fixed value

xx xx Offset of the first IFD

The data following this header is supposed to be the actual “attribute information” that is organized in so-called IFDs (Image File Directory) that are data records of a specific format. Each IFD consists of the following data:

IFD record

xx xx IFD tag

xx xx Data type

xx xx xx xx Number of data records of the same data type

xx xx xx xx Offset of the actual data, from the beginning of the EXIF

The malware’s parser carefully traverses each record until it finds the one with a tag ’25 88′ (0x8825 little endian). This is the tag value for “GPS Info”. That IFD record is, in turn, a list of tagged IFD records that hold separate values for latitude, longitude, timestamp, speed, etc. In our case, the code is looking for the tags ‘2’ (latitude) and ‘4’ (longitude). The data for latitude and longitude are stored as three values in the “rational” format : two 32-bit values, the first is the enumerator and the second one is the denominator. Each of these three values corresponds to degrees, minutes and seconds, respectively.

Then, for each record of interest, the code extracts the enumerator part and produces a string of three integers (i.e. “97 30 4294967121” and “4294967178 140 4294967274″ that will be displayed by a typical EXIF parser as 1193143 deg 55′ 21.00″, 4296160226 deg 47′ 54.00”). Then, curiously enough, it uses sscanf() to convert these strings back to integers. This may indicate that the GPS Info parser was taken from a third-party source file and used as-is. The extracted integers are then used to produce an actual IP address. The pseudocode in C is as follows:

const char lat[] = "97 30 4294967121"; // from Exif data

const char lon[] = "4294967178 140 4294967274"; // from Exif data

int o1p1, o1p2, o2p1, o3p1, o3p2, o4p1;

uint8_t octets[4];

sscanf(lat, "%d %d %d", &o1p2, &o1p1, &o2p1);

sscanf(lon, "%d %d %d", &o3p2, &o3p1, &o4p1);

octets[0] = o1p1 + ( o1p2 + 0x5A );

octets[1] = o2p1 + ( o1p2 + 0x5A );

octets[2] = o3p1 + ( o3p2 + 0xB4 );

octets[3] = o4p1 + ( o3p2 + 0xB4 );

printf("%u.%u.%u.%u\n", octets[0], octets[1], octets[2], octets[3]);

The implementation of the EXIF parser appears to be pretty generic. The fact that it correctly handles the byte order (swapping the data, if required) and traverses all EXIF records skipping them correctly, and that the GPS data is converted to a string and then back to integers most likely indicates that the code was reused from an EXIF-parsing library or toolkit.

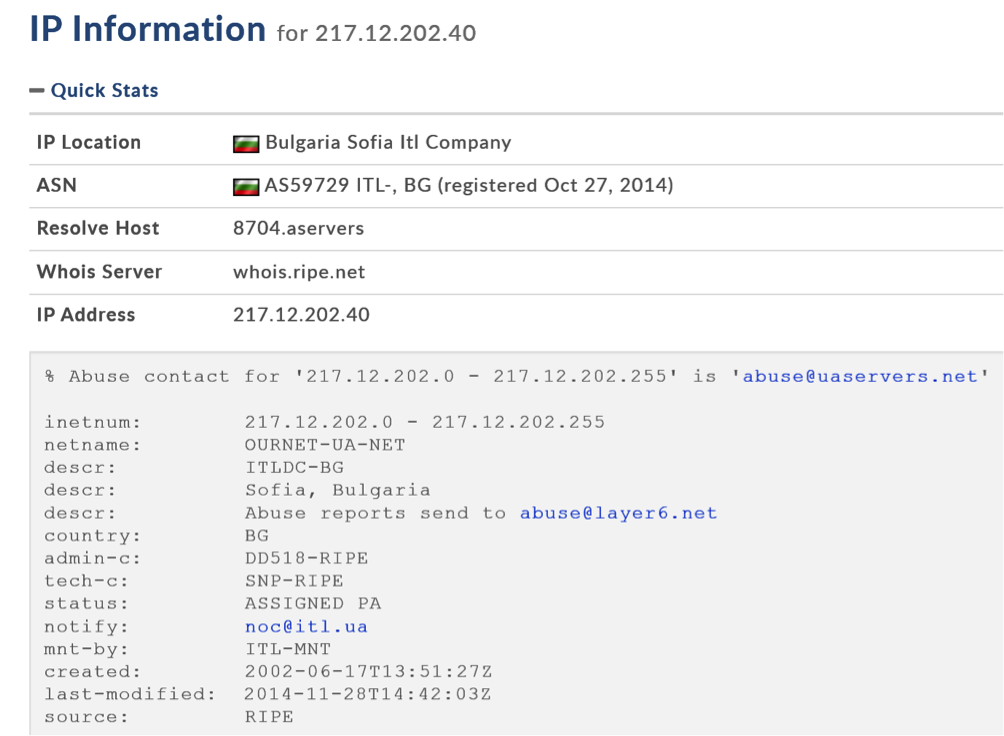

For the values provided here, the code will produce the IP address “217.12.202.40” that is a known C&C of VPNFilter.

It should be noted that this IP is included in Cisco Talos’ IOCs list as a known C&C. Currently, it appears to be down.

What’s next?

Perhaps the most interesting question is who is behind VPNFilter. In their Affidavit for sinkholing the malware C2, FBI suggests it is related to Sofacy:

Interestingly, the same Affidavit contains the following phrase: “Sofacy Group, also known as apt28, sandworm, x-agent, pawn storm, fancy bear and sednit”. This would suggest that Sandworm, also known as BlackEnergy APT, is regarded as subgroup of Sofacy by the FBI. Most threat intel companies have held these groups separate before, although their activity is known to have overlapped in several cases.

Perhaps the most interesting technical detail, which Cisco Talos points in their blog linking VPNFilter to BlackEnergy, is the usage of a flawed RC4 algorithm.The RC4 key scheduling algorithm implementation from these is missing the typical “swap” at the end of the loop. While rare, this mistake or perhaps optimization from BlackEnergy, has been spotted by researchers and described publicly going as far back as 2010. For instance, Joe Stewart’s excellent analysis of Blackenergy2 explains this peculiarity.

So, is VPNFilter related to BlackEnergy? If we are to consider only the RC4 key scheduling implementation alone, we can say there is only a low confidence link. However, it should be noted that BlackEnergy is known to have deployed router malware going back as far as 2014, which we described in our blogpost: “BE2 custom plugins, router abuse, and target profiles“. We continue to look for other similarities which could support this theory.

VPNFilter EXIF to C2 mechanism analysed

John

Is it possible to get a sample for one of the jpg images? I want to dynamically analyse the stage 1 sample but the C&C servers are down and I can’t get the malware to download the picture. I want to simulate my own server for that. thanks 🙂

Jeremy Crawford

Due to what I’ve been told, I believe that at the end of the metaphorical loop in a sense perhaps the apt groups maybe investing in some sort of stock I could be wrong however who knows with these guys!