Targeted attacks and malware campaigns

Go Zebrocy

Zebrocy was first observed being used as a Sofacy backdoor in 2015. However, the collection of cases where this tool has been used mean that we consider it a subset of activity in its own right. On the basis of this threat actor’s past behaviour, we predicted last year that Zebrocy would continue to innovate in its malware development. The group has developed using Delphi, AutoIT, .NET, C# and PowerShell. Since May 2018, Zebrocy has added the “Go” language to its arsenal – the first time that we have observed a well-known APT threat actor deploy malware with this compiled open-source language.

Zebrocy continues to target government-related organizations in Central Asia, both in-country and in remote locations, as well as a new diplomatic target in the Middle East. The group also continued to innovate. Much of the spear-phishing remains thematically the same and continues to be characteristically high volume for a targeted attacker – a trend that is likely to continue. However, the remote locations of the Central Asian targets are becoming more spread out – including South Korea, the Netherlands and others. The focus to date has been on Windows, but we expect the group to continue making further innovations within its malware set – perhaps all their components will soon support every platform used by their victims, including Linux and Mac OS.

GreyEnergy overlap with Zebrocy

GreyEnergy is believed to be a successor to the BlackEnergy group (aka Sandworm), best known for its involvement in attacks on Ukrainian energy facilities in 2015 that led to power outages. Like its predecessor, GreyEnergy has been detected attacking industrial and ICS targets, mainly in Ukraine.

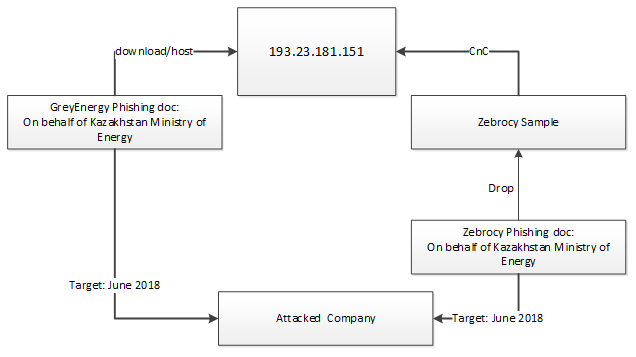

Kaspersky Lab ICS CERT has identified an overlap between GreyEnergy and Zebrocy.

No direct evidence exists as to the origins of GreyEnergy, but the links between GreyEnergy and Zebrocy suggest the groups are related. Kaspersky Lab researchers have detailed how both groups shared the same C2 (command-and-control) server infrastructure for a certain period of time and how both targeted the same organization almost simultaneously, which more or less confirms the relationship between the two.

Chafer uses Remexi malware to spy on Iran-based diplomatic agencies

Throughout autumn 2018, we analyzed a long-standing (and still active at that time) cyber-espionage campaign that primarily targeted foreign diplomatic entities in Iran. The attackers used an improved version of the Remexi malware, previously associated with an APT threat actor that Symantec calls Chafer. This group has been observed since at least 2015, but based on things such as compilation time-stamps, and C2 registration, it’s possible that the group has been active for even longer. Traditionally, Chafer has focused on targets inside Iran, although its interests clearly include other countries in the Middle East.

The attackers rely heavily on Microsoft technologies on both client and server sides. The Trojan uses standard Windows utilities such as the Microsoft BITS (Background Intelligent Transfer Service) “bitsadmin.exe” to receive commands and exfiltrate data. This data includes keystrokes, screenshots, and browser-related data such as cookies and history, decrypted where possible. The C2 is based on IIS using .ASP technology to handle the victims’ HTTP requests.

New zero-day vulnerability exploited by APT threat actors

In February, our AEP (Automatic Exploit Prevention) systems detected an attempt to exploit a vulnerability in Windows – the fourth consecutive exploited Local Privilege Escalation vulnerability in Windows that we have discovered recently using our technologies. Further analysis led us to uncover a zero-day vulnerability in “win32k.sys”. We reported this to Microsoft on February 22, who confirmed the vulnerability and assigned it CVE-2019-0797. Microsoft released a patch on March 12, 2019, crediting Kaspersky Lab researchers Vasiliy Berdnikov and Boris Larin with the discovery. Just as with CVE-2018-8589, we believe that this exploit is being used by several threat actors, including, but possibly not limited to, FruityArmor and SandCat. While FruityArmor is known to have used zero-days before, SandCat is a new APT actor that we discovered only recently.

Lazarus continues to target crypto-currency exchanges

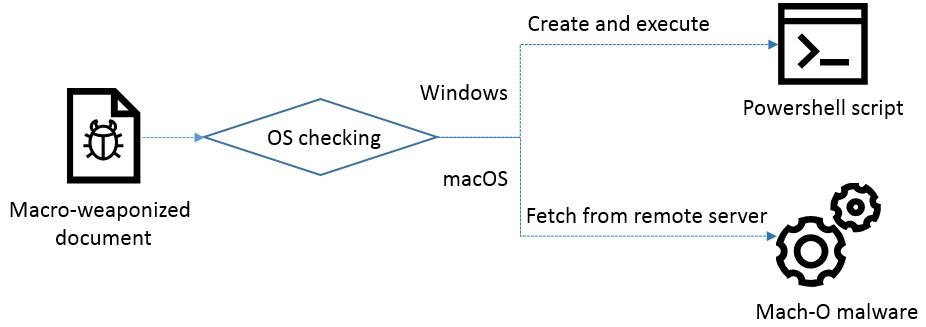

The Lazarus APT group is well-known for targeting financial organizations. In the middle of 2018, we published our report on ‘Operation AppleJeus‘, highlighting the threat actor’s focus on crypto-currency exchanges, using a fake company with a backdoored product aimed at crypto-currency businesses. One of the key findings was the group’s new ability to target Mac OS. Since then, Lazarus has expanded its operations for this platform. Further tracking of the group’s activities enabled us to discover a new operation, active since at least November 2018, which utilizes PowerShell to control Windows systems and Mac OS malware to target Apple customers.

The Lazarus group continues to update its TTPs (Tactics, Techniques and Procedures) to help it fly under the radar. We would urge organizations involved in the booming crypto-currency or technological startup industry to exercise extra caution when dealing with new third parties or installing software. It’s best to check new software with an anti-virus program or at least use popular free virus-scanning services such as VirusTotal. You should never set ‘Enable Content’ (macro scripting) in Microsoft Office documents received from new or untrusted sources. If you need to try out new applications, it’s better to do so offline or on an isolated network virtual machine which you can erase with a few clicks. For more details on this and other research, you can subscribe to our APT intelligence reports.

Under the [Shadow]Hammer

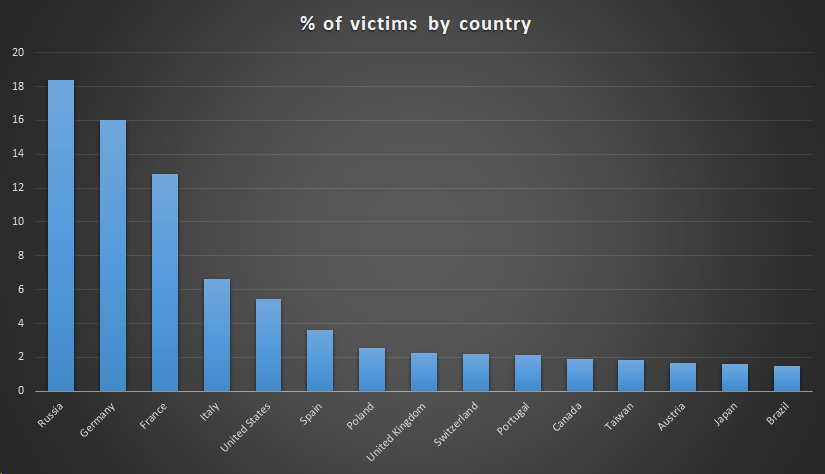

In January, we discovered a sophisticated supply-chain attack involving the ASUS Live Update Utility, used to deliver BIOS, UEFI and software updates to ASUS laptops and desktops. The attackers added a backdoor to the utility and then distributed it to users through official channels. ASUS has a wide install base, making this an attractive target for APT threat actors. The compromised version of the utility was distributed to a large number of people between June and November 2018. Our telemetry shows that 57,000 Kaspersky Lab customers downloaded and installed it, although we believe the real scale of the problem is much bigger, possibly affecting over a million users worldwide.

The goal of the attack was to surgically target an unknown pool of users, identified by their network adapter MAC addresses. The attackers hardcoded a list of MAC addresses in the Trojanized samples, which identifies the true targets of this massive operation. We were able to extract over 600 unique MAC addresses from more than 200 samples discovered in this attack, although it’s possible that other samples exist which target different MAC addresses. You can check if your MAC address is on the target list here.

Other malware news

Razy Trojan steals crypto-currency

While many browser extensions make our lives easier, some are altogether more dangerous, bombarding us with advertising or collecting information about our activities. Some are even designed to steal money. We recently reported the Razy Trojan, malware that installs a malicious browser extension on the victim’s computer or infects an already installed extension. To do so, it disables the integrity check for installed extensions and automatic updates for the targeted browser. The Trojan works with Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox and Yandex browsers, though it has different infection scenarios for each browser type. Razy spreads via advertising blocks on websites and is distributed from free file-hosting services under the guise of legitimate software. Razy serves several purposes, mostly related to the theft of crypto-currency. Its main tool, the script ‘main.js’, is capable of searching for addresses of crypto-currency wallets on websites and replacing them with the attacker’s wallet addresses, spoofing images of QR codes pointing to wallets, modifying the web pages of crypto-currency exchanges and spoofing Google and Yandex search results.

Turning ATMs into slot machines

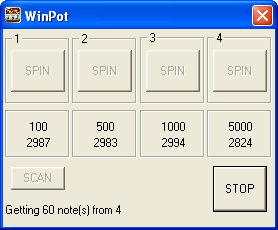

‘Jackpotting’ refers to the fraudulent methods used by criminals to obtain cash from ATMs. One recent example is the WinPot malware. The malware is notable because the criminals designed the user interface to resemble a slot machine.

However, unlike the machines in a casino, an ATM infected with WinPot always pays out – to the criminals. The malware window displays the denomination of banknotes for each cassette, so that the money mule operating the malware just needs to select the cassette with the most money in it and press ‘Spin’. The ‘Scan’ button can be used to recount the notes. The authors also include an emergency ‘Stop’ button, to allow the mule to cut short the pay out so as not to arouse suspicion.

There are several versions of the malware, and while their core functionality is essentially the same, there are some differences. For example, some versions will only dispense cash for a limited period of time and then they deactivate themselves. As with Cutlet Maker, WinPot is available on the Darknet for between $500 and $1,000, depending on the version.

To block attacks of this kind, we recommend that banks adopt device control and allowlisting. The former will block attempts to implant malware in the ATM using a USB device, while the latter will prevent execution of unauthorized software on the ATM. Kaspersky Embedded Systems Security can be used to secure ATMs.

Pirate Matryoshka

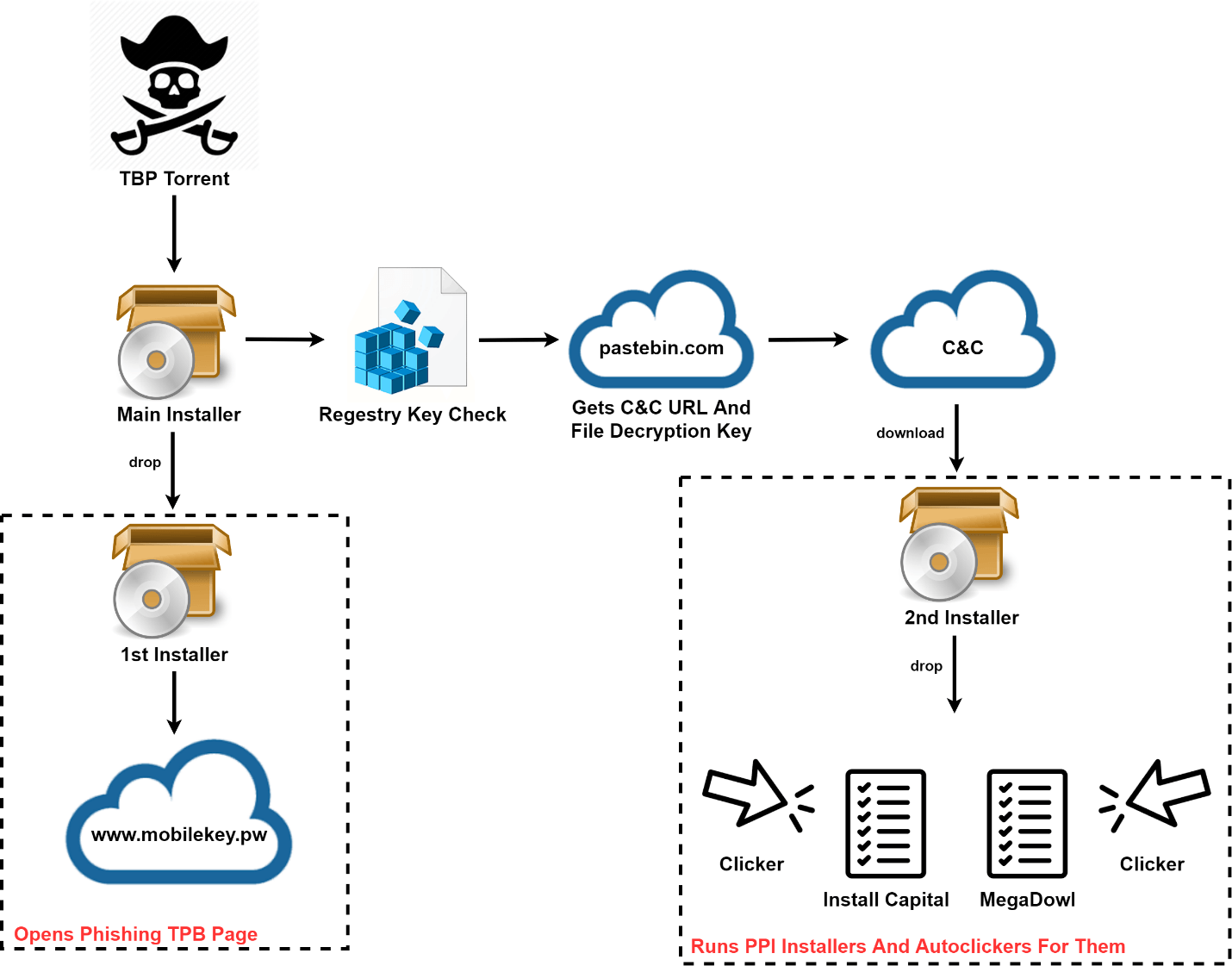

Using torrent trackers to spread malware is a well-known practice: cybercriminals disguise it as popular software, computer games, media files and other sought-after content. Earlier this year we detected one such campaign, when The Pirate Bay (TPB) tracker filled up with harmful files used to distribute malware under the guise of cracked copies for paid programs. The tracker contained malicious torrents created from dozens of different accounts, including those registered on TBP for quite some time. Instead of the expected software, the downloaded file was a Trojan, Pirate Matryoshka, whose basic logic was implemented by SetupFactory installers.

During the initial stage, the installer decrypts another SetupFactory installer to display a phishing web page. This page opens directly in the installation window and requests the user’s TBP account credentials, supposedly to continue the process. The second downloaded component is also a SetupFactory installer, used to decrypt and run four PE files in sequence. The second and fourth of these files are downloaders for the InstallCapital and MegaDowl file partner programs (which Kaspersky Lab classifies as adware). These usually find their way on to people’s computers through file sharing sites. Besides downloading the required content, their goal is to install additional software while carefully hiding the option to cancel.

The other two files are auto-clickers written in Visual Basic that are required to prevent the user from canceling the installation of additional software (in which case the cybercriminals would go away empty-handed). The auto-clickers are run before the installers: when the installer windows are detected, they check the boxes and click the buttons needed to give the user’s consent to install the unnecessary software.

Pirate Matryoshka results in the victim being flooded with unwanted programs. The owners of file partner programs often do not track the programs offered in their downloaders: our research shows that one in five files offered by partner installers is malicious, including pBot, Razy and others.

Mirai now used to target enterprise devices

Researchers from Palo Alto Networks’ Unit 42 recently reported a new variant of Mirai, the infamous IoT botnet. This malware is best known for its use in a massive DDoS attack on the servers of DNS provider Dyn, in 2016. The botnet is now equipped with a much wider range of exploits, which makes it even more dangerous and allows it to spread faster.

More troubling is the fact that the new strain is targeting not only its usual victims – routers, IP cameras, and other ‘smart’ things – but also enterprise IoT devices. This is no surprise since the Mirai source code was leaked some time ago, allowing any attacker with sufficient programming skills to use it. This explains why this botnet features highly in our report, ‘DDoS attacks in Q4 2018‘; and the fact that, in our report, ‘New trends in the world of IoT threats‘, Mirai is responsible for 21% of all IoT infections.

It is possible that future waves of Mirai infections might even include industrial IoT devices.

To reduce the risk of Mirai infection, we recommend that you install patches and firmware updates as soon as they become available, monitor traffic coming from each device for abnormalities, change default passwords and enforce an effective password policy for staff and re-boot any device that is behaving strangely (this will remove the malware from the device, but will not, on its own, prevent re-infection. To help companies protect themselves against the latest IoT-related threats we have released a new intelligence data feed for IoT-related threats.

‘Collection #1’ and other data leaks

On January 17, security researcher Troy Hunt reported a leak of more than 773 million email addresses and 21 million unique passwords. The data, dubbed ‘Collection #1’, was originally shared on the popular cloud service MEGA. Collection #1 is just a small part of a bigger leak of about 1TB of data, split into seven parts and distributed through a data-trading forum. The full package is a collection of credentials leaked from different sources during the past few years, the most recent being from 2017, so we were unable to identify any more recent data in this ‘new’ leak. The new data dump, dubbed ‘Collection #2-5’, was discovered by researchers at the Hasso Plattner Institute in Potsdam.

In February, further data dumps occurred. Details of 617 million accounts, stolen from 16 hacked companies, were put up for sale on Dream Market, accessible via the Tor network. The hacked companies include Dubsmash, MyFitnessPal, Armor Games and CoffeeMeetsBagel. Subsequently, data from a further eight hacked companies was posted to the same market place. Then in March, the hacker behind the earlier data dumps posted stolen data from a further six companies.

One of the particularly worrying aspects of these leaks is the fact that not all of the companies affected had previously reported the data breaches.

The impact on a company affected by a data breach goes beyond the loss of data. It includes the costs of investigating the breach, closing any security loopholes and maintaining business continuity. On top of that, a company’s reputation can be affected, especially if it becomes clear that the company failed to take adequate steps to secure the personal data of its customers.

The impact on customers can also be dramatic, especially if they use the same login credentials to access other online services. You can find our advice on how to mitigate the impact of a data breach here.

Social engineering

In our threat predictions for 2019, we described social engineering as the most successful infection vector ever and indicated why we thought it would remain so. The key to its success lies in sparking the curiosity of potential victims. Massive data leaks, such as the ones discussed above, help attackers to fine-tune their approach, making it more successful. Phishers will latch on to any topic that they think will pique the interest of their victims. We saw this recently in a campaign that hooked into events in Venezuela.

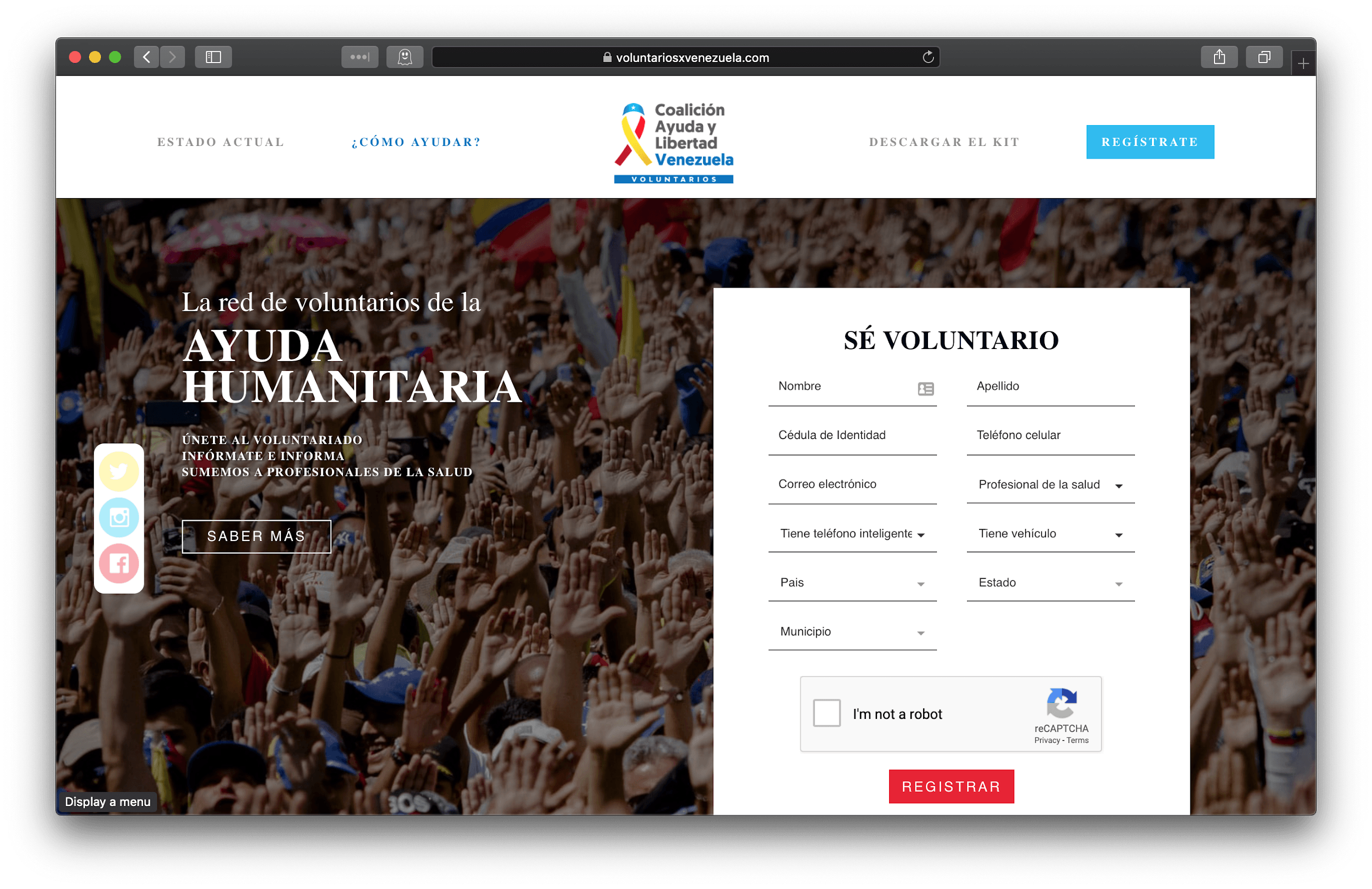

On February 10, Juan Guaido made a public call for volunteers to join a new movement called ‘Voluntarios por Venezuela’ (Volunteers for Venezuela), to help international organizations deliver humanitarian aid to the country. The original website asks volunteers to provide their full name, personal ID, cell phone number, and whether they have a medical degree, a car, or a smartphone, and also their location. The volunteers sign up and then receive instructions on how to help.

Just a few days after the legitimate site appeared, an almost identical website appeared. Both the legitimate and fake sites used SSL from Let’s Encrypt. The scariest aspect was that these two different domains, with different owners, were resolved within Venezuela to the same IP address, belonging to the fake domain owner. So it didn’t matter if a volunteer opened the legitimate domain name or the fake one – in the end their personal information was injected into a fake site.

In this scenario, where DNS servers are being manipulated, we would strongly recommend using public DNS servers such as Google DNS servers (8.8.8.8 and 8.8.4.4) or CloudFlare and APNIC DNS servers (1.1.1.1 and 1.0.0.1). We also recommend using VPN connections without a third-party DNS.

LockerGoga ransomware attacks

Ransomware continues to be a problem for consumers and businesses alike, notwithstanding a relative decline in numbers in the last two years. In 2018, we blocked 765,538 crypto-ransomware attacks on computers protected by Kaspersky Lab products, of which around 220,000 included corporate customers.

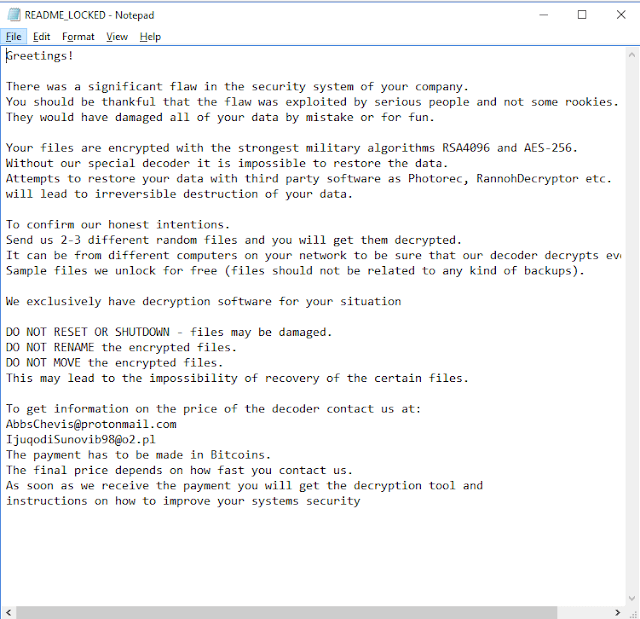

The most recent to hit the headlines is LockerGoga, which recently compromised the systems of Altran, Norsk Hydro and other companies. It’s unclear who’s behind the attacks, what they want and the mechanism used to first infect its victims. It’s not even clear if LockerGoga is ransomware or a wiper. The malware encrypts data and displays a ransom note asking victims to get in touch to arrange decryption, in return for an (unspecified) payment in bitcoins.

However, later versions were observed by researchers that forcibly log victims off infected systems by changing their passwords, and removing their ability to even log back in to the system. In such cases, the victims may not even get to see the ransom note.

19-year-old bug in WinRAR

Recently, researchers from Check Point discovered a long-standing vulnerability in the popular WinRAR utility – used by around 500 million people worldwide. This path traversal zero-day vulnerability (CVE-2018-20250) enables attackers to specify arbitrary destinations during file extraction of ‘ACE’-formatted files, regardless of user input.

This vulnerability has been fixed in the latest version of WinRAR (5.70), but since WinRAR itself does not contain an auto-update feature, it’s probable that many existing users will continue to run out-of-date versions.

The internet of secure, and not so secure, things

The use of smart devices is increasing. Some forecasts suggest that by 2020 the number of smart devices will exceed the world’s population several times over. These include household objects such as TVs, smart meters, thermostats, baby monitors and children’s toys, as well as cars, medical devices, CCTV cameras and parking meters. This offers a broad attack surface for anyone looking to take advantage of security weaknesses – for whatever purpose. Sadly, all too often we see reports of vulnerabilities in smart devices that could leave both consumers and organizations open to attack.

In February, at MWC19, researchers from our ICS CERT presented a report on the security of artificial limbs developed by Motorica. They looked at three aspects: firmware, the handling of data and the security of data in the cloud.

On the plus side, they found no vulnerabilities in the firmware of the prosthetic limbs themselves, or in the handling of data – since data flows one way only, from the limb to the cloud, it’s not possible to hack the device and take control of it remotely. However, they did find flaws in the development of the cloud infrastructure that could allow an attacker to gain access to data from the smart limb.

Werner Schober, a researcher at SEC Consult took an intimate look at the security of a sex toy. The device, designed to connect to an Android or iOS smartphone using Bluetooth, is controlled through a special app, either locally or remotely. On top of this, the app features a fully-fledged social network with group chats, photo galleries, friend-lists and more. The researcher was able to access the data of all users of the device, including usernames, passwords, chats, images and videos. Even worse, he was able to find a way to control the devices of other users. There was no mechanism for updating the firmware. However, he was able to find interfaces on the device that the manufacturer had used for debugging purposes and forgotten to close.

Researchers at Pen Test Partners recently discovered a flaw that exposes the sensitive data of children wearing GPS tracking watches, including their name, parents’ details and real-time location information. This was because of a secure privilege escalation vulnerability. The system failed to validate that the user had the appropriate permission to obtain admin control, so that an attacker with access to the watch’s credentials could change the permissions at the backend, exposing access to the account information and data stored on the watch.

It’s essential that vendors consider security when products are being designed. However, it’s also vital that consumers consider security before buying any connected device. This includes disabling functions that you don’t need – or even asking yourself if you need a connected version of the device at all. It also means looking online for information about any vulnerabilities that may have been reported and checking to see if it’s possible to update the firmware on the device. Finally, it’s important to change the default password and replace it with a unique, complex password. You can use the free Kaspersky IoT Scanner to check your Wi-Fi network and tell you if the devices connected to it are safe.

IT threat evolution Q1 2019