Q1 2014 in figures

- According to KSN data, Kaspersky Lab products blocked a total of 1 131 000 866 malicious attacks on computers and mobile devices in the first quarter of 2014.

- Kaspersky Lab solutions repelled 353 216 351 attacks launched from online resources located all over the world.

- Kaspersky Lab’s web antivirus detected 29 122 849 unique malicious objects: scripts, exploits, executable files, etc.

- 81 736 783 unique URLs were recognized as malicious by web antivirus.

- 39% of web attacks neutralized by Kaspersky Lab products were carried out using malicious web resources located in the US and Russia.

- Kaspersky Lab’s antivirus solutions detected 645 809 230 virus attacks on users’ computers. A total of 135 227 372 unique malicious and potentially unwanted objects were identified in these incidents.

Overview

Targeted attacks/APT

The fog clears further

In September 2013 we reported on a targeted attack called Icefog, focused mainly on targets in South Korea and Japan. Most APT campaigns are sustained over months or years, continuously stealing data from their victims. By contrast, the attackers behind Icefog focused on their victims one at a time, in short-lived, precise hit-and-run attacks designed to steal specific data. The campaign, operational since at least 2011, involved the use of a series of different versions of the malware, including one aimed at Mac OS.

Following publication of our report, Icefog operations ceased and the attackers closed down all of the known command-and-control servers. However, we continued to monitor the operation by sinkholing domains and analyzing victim connections. Our ongoing analysis revealed the existence of another generation of Icefog backdoors – this time, a Java version of the malware that we called ‘Javafog’. Connections to one of the sinkholed domains, ‘lingdona[dot]com’, indicated that the client could be a Java application; and subsequent investigation turned up a sample of this application (you can find the details of the analysis here).

During the sinkholing operation for this domain, we observed eight IP addresses for three unique victims of Javabot. All of them were located in the United States – one was a very large independent oil and gas corporation with operations in many countries. It’s possible that Javafog was developed for a US-specific operation, one that was designed to be longer than the typical Icefog attacks. One probable reason for developing a Java version of the malware is that it is more stealthy and harder to detect.

Behind the mask

In February, the Kaspersky lab security research team published a report on a complex cyber-espionage campaign called The Mask or Careto (Spanish slang for ‘ugly face’ or ‘mask’). This campaign was designed to steal sensitive data from various types of targets. The victims, located in 31 countries around the world, include government agencies, embassies, energy companies, research institutions, private equity firms and activists – you can find the full list here.

The attacks start with a spear-phishing message containing a link to a malicious website containing a number of exploits. Once the victim is infected, they are then redirected to the legitimate site described in the e-mail they received (e.g. a news portal, or video). The Mask includes a sophisticated backdoor Trojan capable of intercepting all communication channels and of harvesting all kinds of data from the infected computer. Like Red October and other targeted attacks before it, the code is highly modular, allowing the attackers to add new functionality at will. The Mask also casts its net wide – there are versions of the backdoor for Windows and Mac OS X and there are references that suggest there may also be versions for Linux, iOS and Android. The Trojan also uses very sophisticated stealth techniques to hide its activities.

The key purpose of the attackers behind The Mask is to steal data from their victims.

The malware collects a range of data from the infected system, including encryption keys, VPN configurations, SSH keys, RDP files and some unknown file types that could be related to bespoke military/government-level encryption tools.

We don’t know who’s behind the campaign. Some traces suggest the use of the Spanish language but it doesn’t help pin it down, since this language is spoken in many parts of the world. It’s also possible that this could have been used as a false clue, to divert attention from whoever wrote it. The very high degree of professionalism of the group behind this attack is unusual for cybercriminal groups – one indicator that The Mask could be a state-sponsored campaign.

This campaign underlines the fact that there are highly-professional attackers who have the resources and the skills to develop complex malware – in this case, to steal sensitive information. It also highlights once again the fact that targeted attacks, because they generate little or no activity beyond their specific victims, can ‘fly under the radar’.

But it’s equally important to recognize that, notwithstanding the sophistication of The Mask, the starting-point (as with many previous targeted attacks) involves tricking individuals into doing something that undermines the security of the organization they work for – in this case, by clicking on a link.

Currently, all known C&C (Command-and-Control) servers used to manage infections are offline. But it’s possible for the attackers to renew the campaign in the future.

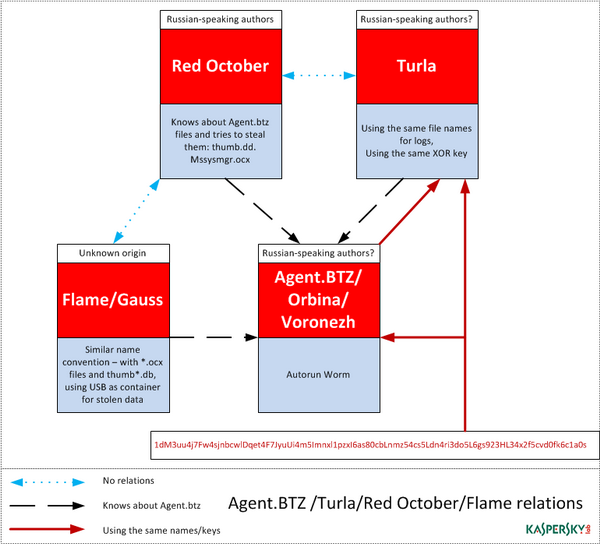

The worm and the snake

Early in March there was widespread discussion within the IT security community about a cyber-espionage campaign called Turla (also known as Snake and Uroburos). Researchers at G-DATA think the malware used may have been created by Russian special services. Research carried out by BAE Systems linked Turla to malware called ‘Agent.btz’ that dates back to 2007 and was used in 2008 to infect the local networks of US military operations in the Middle East.

Kaspersky Lab became aware of this targeted campaign while investigating an incident involving a highly sophisticated rootkit, which we called ‘Sun rootkit’. It became apparent that the ‘Sun rootkit’ and Uroburos were one and the same threat.

We’re still investigating Turla, which we believe is far more complex than is suggested by the materials that have been published so far. However, our initial analysis has turned up some interesting connections.

Agent.btz is a self-replicating worm, able to spread via USB flash drives using a vulnerability enabling it to launch using ‘autorun.inf’. This malware was able to spread rapidly across the globe. Even though no new variants of the worm have been created for several years, and the above-mentioned vulnerability has been closed in newer versions of Windows, in 2013 alone we detected Agent.btz 13,832 times in 107 countries!

The worm creates a file called ‘thumb.dll’ on all USB flash drives connected to the infected computer (containing the files ‘winview.ocx’, ‘wmcache.nld’ and ‘mssysmgr.ocx ‘). This file is a container for stolen data that is saved to the flash drive if it can’t be sent directly over the Internet to the control-and-command server managed by the attackers. If such a flash drive is then inserted into another computer, the ‘thumb.dll’ file is copied to the new computer with the name ‘mssysmgr.ocx.

We believe that the scale of the epidemic, coupled with the above functionality, means that there are tens of thousands of USB flash drives around the world containing files called ‘thumb.dll’ created by Agent.btz. Currently, most variants of this malware are detected by Kaspersky Lab as ‘Worm.Win32.Orbina’.

Of course, Agent.btz isn’t the only malware that spreads via USB flash drives.

The ‘USB Stealer’ module in Red October includes a list of files that it looks for on USB flash drives connected to infected computers. We noticed that this list includes the files ‘mysysmgr.ocx’ and ‘thumb.dll’, i.e. two of the files written to flash drives by Agent.btz.

Looking back further, when we analysed Flame, and its cousins Gauss and miniFlame, we also noticed similarities with Agent.btz. There is an analogous naming convention, especially the use of the ‘.ocx’ extension. In addition, it was also clear that both Gauss and miniFlame were aware of the ‘thumb.dll’ file and looked for it on USB flash drives.

Finally, Turla uses the same file names as Agent.btz for the log it stores on infected computers – ‘mswmpdat.tlb’, ‘winview.ocx’ and ‘wmcache.nld’. It also uses the same XOR key to encrypt its log files.

All these points of comparison can be found below.

So far, all we know is that all of these malicious programs share some points of similarity. It’s clear that Agent.btz was a source of inspiration for those who developed the other malware. But we’re not able to say for sure if it was the same people behind all these threats.

Malware stories: peeling the onion

Tor (short for The Onion Router) is software designed to allow someone to remain anonymous when accessing the Internet. It has been around for some time, but for many years was used mainly by experts and enthusiasts. However, use of the Tor network has spiked in recent months, largely because of growing concerns about privacy. Tor has become a helpful solution for those who, for any reason, fear the surveillance and the leakage of confidential information. However, it’s clear from investigationswe have conducted in recent months that Tor is also attractive to cybercriminals: they also value the anonymity it offers.

In 2013 we started to see cybercriminals actively using Tor to host their malicious malware infrastructure and Kaspersky Lab experts have found various malicious programs that specifically use Tor. Investigation of Tor network resources reveals lots of resources dedicated to malware, including Command-and-Control servers, administration panels and more. By hosting their servers in the Tor network, cybercriminals make them harder to identify, denylist and eliminate.

Cybercriminal forums and market places have become familiar on the ‘normal’ Internet. But recently a Tor-based underground marketplace has also emerged. It all started with the notorious Silk Road market and has evolved into dozens of specialist markets – for drugs, arms and, of course, malware.

Carding shops are firmly established in the Darknet, where stolen personal information is for sale, with a wide variety of search attributes like country, bank etc. The goods on offer are not limited to credit cards: dumps, skimmers and carding equipment are for sale too.

A simple registration procedure, trader ratings, guaranteed service and a user-friendly interface – these are standard features of a Tor underground marketplace. Some stores require sellers to deposit a pledge – a fixed sum of money – before starting to trade. This is to ensure that a trader is genuine and his services are not a scam or of poor quality.

The development of Tor has coincided with the emergence of the anonymous crypto-currency, Bitcoin. Nearly everything on the Tor network is bought and sold using Bitcoins. It’s almost impossible to link a Bitcoin wallet and a real person, so conducting transactions in the Darknet using Bitcoin means that cybercriminals can remain virtually untraceable.

It seems likely that Tor and other anonymous networks will become a mainstream feature of the Internet as increasing numbers of ordinary people using the Internet seek a way to safeguard their personal information. But it’s also an attractive mechanism for cybercriminals – a way for them to conceal the functions of the malware they create, to trade in cybercrime services and to launder their illegal profits. We believe that we’re only seeing the start of their use of these networks.

Web security and data breaches

The ups and downs of Bitcoin

Bitcoin is a digital crypto-currency. It operates on a peer-to-peer model, where the money takes the form of a chain of digital signatures that represent portions of a Bitcoin. There is no central controlling authority and there are no international transaction charges – both of which have contributed to making it attractive as a means of payment. You can find an overview of Bitcoin, and how it works, on theKaspersky Daily website.

As use of Bitcoin has increased, it has become a more attractive target for cybercriminals.

In our end-of-year forecasts, we anticipated attacks on Bitcoin, specifically saying that ‘attacks on Bitcoin pools, exchanges and Bitcoin users will become one of the most high-profile topics of the year’. Such attacks, we said, ‘will be especially popular with fraudsters as their cost-to-income ratio is very favorable’.

We’ve already seen ample evidence of this. Mt.Gox, one of the biggest Bitcoin exchanges, was taken offline on 25 February. This followed a turbulent month in which the exchange was beset by problems – problems that saw the trading price of Bitcoins on the site fall dramatically. There have been reports that the exchange’s insolvency followed a hack that led to the loss of 744,408 Bitcoins – worth around $350 million at the point Mt.Gox was taken offline. It seems that transaction malleability was the central issue here. This is a problem with the Bitcoin protocol that, under certain circumstances, allows an attacker to issue different transaction IDs for the same transaction, making it appear as though the transaction hadn’t happened. You can read our appraisal of the issues surrounding the collapse of Mt.Gox here. The transaction malleability flaw has now been fixed. Of course, Mt.Gox isn’t the only virtual banking services provider that has been attacked, as we discussed towards the end of last year. The growing use of virtual currencies is sure to mean more attacks in the future.

It’s not just virtual currency exchanges that are susceptible to attack. People using crypto-currencies can also find themselves targeted by cybercriminals. In mid-March, the personal blog and Reddit account of Mt.Gox CEO, Mark Karepeles, were hacked. These accounts were used to post a file, ‘MtGox2014Leak.zip’. Supposedly, this file contained valuable database dumps and specialized software allowing remote access to Mt.Gox data. What it actually contained was malware designed to locate and steal Bitcoin wallet files. Our write-up of the malware can be found here. This provides a clear example of how cybercriminals manipulate people’s interest in hot news as a way of spreading malware.

One matter of great importance thrown up by all such attacks is how those of us who make use of any crypto-currency secure ourselves in an environment where – unlike with real-world currencies – there are no external standards and regulations. Our advice is to store your Bitcoins in an open-source offline Bitcoin client (rather than in online stock exchange services with an unknown track record); and if you have a lot of Bitcoins – keep them in a wallet on a PC that’s not connected to the Internet. On top of this, make passphrases for your Bitcoin wallet as complex as possible and ensure that your computer is protected with a good Internet security product.

Spammers are also quick to make use of social engineering techniques to draw people into a scam. They took advantage of the climb in the price of Bitcoins in the first part of this quarter (prior to the Mt.Gox collapse) to try to cash in on people’s desire to get rich quick. As we outlined in February, there were several Bitcoin-related topics used by spammers. They included offers to share secrets from a millionaire on how to get rich by investing in Bitcoins; and offers to join a Bitcoin lottery.

Good software that could be used for bad purposes

In February, at the Kaspersky Security Analyst Summit 2014, we outlined how improper implementation of anti-theft technologies residing in the firmware of commonly used laptops and some desktop computers could become a powerful weapon in the hands of cybercriminals.

Our research started when a Kaspersky Lab employee experienced repeated system process crashes on one of his personal laptops. Analysis of the event log and a memory dump revealed that the crashes resulted from instability in modules named ‘identprv.dll’ and ‘wceprv.dll’ that were loaded in the address space of one of the system service host processes (‘svchost.exe’). These modules were created by Absolute Software, a legitimate company, and are part of the Absolute Computrace software.

Our colleague claimed that he hadn’t installed the software and didn’t even know it was present on the laptop. This caused us concern because, according to an Absolute Software white paper, the installation should be done by the owner of the computer or their IT service. On top of this, whereas most pre-installed software can be permanently removed or disabled by the owner of the computer, Computrace is designed to survive a professional system cleanup and even a hard disk replacement. Moreover, we couldn’t simply dismiss this as a one-off occurrence, since we found similar indications of the Computrace software running on personal computers belonging to some of our researchers and some enterprise computers. As a result, we decided to carry out an in-depth analysis.

When we first looked at Computrace, we mistakenly thought it was malicious software, because it uses so many tricks that are popular in current malware: it makes use of specific debugging and anti-reverse engineering techniques, injects into the memory of other processes, establishes secret communication, patches system files on disk, encrypts configuration files and drops a Windows executable directly from the BIOS/firmware. This is why, in the past, the software has been detected as malware; although currently, most anti-malware companies allowlist Computrace executables.

We believe that Computrace was designed with good intentions. However, our research shows that vulnerabilities in the software could allow cybercriminals to misuse it. In our view, strong authentication and encryption must be built into such a powerful tool. We found no evidence that Computrace modules had been secretly activated on the computers we analyzed. But it’s clear that there are a lot of computers with activated Comutrace agents. We believe that it’s the responsibility of manufacturers, and Absolute Software, to notify these people and explain how they can deactivate the software if they don’t wish to use it. Otherwise, these orphaned agents will continue to run unnoticed and will provide opportunities for remote exploitation.

Mobile malware

In the last quarter, the percentage of threats targeting Android exceeded 99% of all mobile malware. Detections over the past three months included:

- 1 258 436 installation packages,

- 110 324 new malicious programs for mobile devices,

- 1 182 new mobile banking Trojans.

Mobile banking Trojans

At the start of the year, Kaspersky Lab had logged 1,321 unique executables for mobile banking Trojans, and by the end of the first quarter, that number jumped to 2,503. As a result, over the first three months this year, the number of banking Trojans nearly doubled.

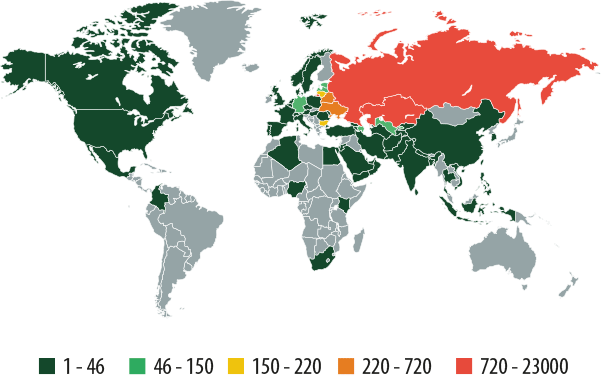

As before, the threats are most active in Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus, and Ukraine:

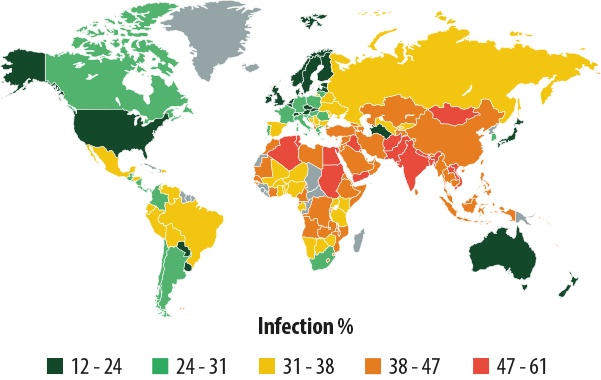

Mobile banking threats around the world in Q1 2014

The Top 10 countries targeted by banking Trojans:

| Country | % of all attacks |

| Russia | 88.85% |

| Kazakhstan | 3.00% |

| Ukraine | 2.71% |

| Belarus | 1.18% |

| Lithuania | 0.62% |

| Bulgaria | 0.60% |

| Azerbaijan | 0.54% |

| Germany | 0.39% |

| Latvia | 0.34% |

| Uzbekistan | 0.30% |

Faketoken is a banking Trojan that entered Kaspersky Lab’s Top 20 most frequently detected threats by the end of the quarter. This threat steals mTANs and works in concert with computer-based banking Trojans. During an online banking session, the computer-based Trojans use a web inject to seed a request on the infected webpage to download an Android application that is allegedly needed in order to conduct secure transactions, but the link actually leads to Faketoken. After the mobile threat ends up on a user’s smartphone, cybercriminals then use the computer-based Trojans to gain access to the victim’s bank account, and Faketoken allows them to harvest mTANs and transfer the victim’s money to their accounts.

We have written several times that most mobile banking threats are designed and initially used in Russia, and that later cybercriminals may use them in other countries. Faketoken is one such program. During the first three months of 2014, Kaspersky Lab detected attacks involving this threat in 55 countries, including Germany, Sweden, France, Italy, the UK, and the US.

New developments from virus writers

TOR-controlled bots

The anonymous Tor network, which is built on a network of proxy servers, offers user anonymity and allows participants to host “anonymous” websites on the .onion domain zone. These websites are then only accessible through Tor. In February, Kaspersky Lab detected the first Android Trojan that is run through a C&C hosted on a domain in the .onion pseudo-zone.

Backdoor.AndroidOS.Torec.a is a modification of Orbot, a commonly used Tor client, in which malicious users have seeded their own code. Note that in order to ensure that Backdoor.AndroidOS.Torec.a is able to use Tor, it needs much more code than for its main function.

The Trojan can receive the following commands from the C&C:

- initiate / stop the interception of incoming text messages

- initiate / stop the theft of incoming text messages

- issue a USSD request

- send data about a telephone (the phone number, country, IMEI, model, OS version) to the C&C

- send a list of apps installed on a mobile device to the C&C

- send text messages to a number specified in a command

Why did malicious users find there was a need for an anonymous network? The answer is simple: a C&C hosted on the Tor network cannot be shut down. Incidentally, the creators of Android Trojans adapted this approach from the virus writers who developed threats targeting Windows.

E-wallet thefts

Malicious users are always on the lookout for new ways to steal money using mobile Trojans. In March, Kaspersky Lab detected Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Waller.a, which in addition to typical SMS Trojan functions is also capable of stealing money from QIWI wallets from infected phones.

Once it receives the appropriate C&C command, the Trojan checks the QIWI wallet balance by sending a text message to the corresponding QIWI system number. The Trojan intercepts the response and sends it to its operators.

If the owner of the infected device has a QIWI wallet account and the Trojan obtains data that there is a positive balance in the wallet account, the malware can transfer money from the user’s account to the QIWI wallet account specified by the cybercriminals. The Trojan owners send a special QIWI system number by text indicating the wallet ID of the malicious users, and the amount to be transferred.

So far, this Trojan has only targeted Russian users. However, cybercriminals can use it to steal cash from users in other countries where text-managed e-wallet systems are commonly used.

Bad news

In the first quarter of 2014, a Trojan targeting iOS was detected. This malicious program is a plug-in for Cydia Substrate, a widely used framework for rooted/hacked devices. There are many affiliate programs for app developers allowing them to promote their apps using the advertising module, and earn money for ad displays. In some advertising modules, the Trojan switches out the ID of the app developers for the malicious users’ ID. As a result, all of the money for ad displays goes to the malicious users instead.

Experts from Turkey have detected a vulnerability exploit causing a denial of service on a device and a subsequent reboot. The point of this vulnerability is that malicious users can take advantage of it to develop an Android app with AndroidManifest.xml, which contains a large amount of data in any name field (AndroidManfiest.xml is a special file found in every Android app). This file contains data about the app, including access permissions for system functions, markers for the processors for different events, etc. A new app can be installed without any issues but, for example, when an activity is called up with a specific name, the device will crash. For instance, a handler can be developed for incoming text messages using the wrong name, and after receiving any text message, the phone would simply crash and become unusable. The device will start to continually reboot, and the user will have only one way of resolving the problem: rolling back the firmware, which will lead to the loss of all of the data stored on the device.

Malicious spam

One of the standard methods used to spread mobile malware is malicious spam. This method is one of the top choices among cybercriminals who use mobile Trojans to steal money from user bank accounts.

Malicious spam texts typically contain either an offer to download an app using a link that points to malware, or a link to a website seeded with a malicious program that redirects users to some sort of offer. Just like with malicious spam in email, cybercriminals rely heavily on social engineering to get the user’s attention.

Olympic-themed spam

The Olympics are a major event, and malicious users took advantage of interest in this year’s Games in Sochi.

In February, we registered SMS spam with links to an alleged broadcast of Olympic events. If a careless user clicked on the link, his smartphone would attempt to load a Trojan detected by Kaspersky Lab as HEUR:Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.FakeInst.fb.

This Trojan is capable of responding to malicious user commands and sending text messages to a major Russian bank and transferring cash from the owner’s mobile account via the infected smartphone. The malicious user can then transfer money from the victim’s account to his own e-wallet. Meanwhile, all of the messages from the bank regarding the transfer will be hidden from the victim.

Spam with links to malicious websites

The cybercriminals who spread the Opfake Trojan sent out SMS spam with a link to specially created malicious websites.

One of the text messages informed recipients that they had received a package and led to a website disguised as the Russian Postal Service.

In other messages, malicious users took advantage of the popularity of the Russian free classifieds website, Avito.ru. These text messages told recipients that they had received an offer in response to their ad, or that someone was interested in buying their item, and included links to a fake Avito.ru page.

Malicious counterfeit websites

If a user clicks on the link leading to the fake website, his smartphone will attempt to download Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Opfake.a. In addition to sending out paid text messages, this malicious program is also used to spread other mobile threats, including the multi-functional Backdoor.AndroidOS.Obad.a.

Social engineering has always been a dangerous tool in the hands of cybercriminals. Internet users need to be cautious and, at the very minimum, refrain from clicking on any links received from unknown senders. In these cases, there is always a risk of falling into a trap set by malicious users and losing money as a result.

Statistics

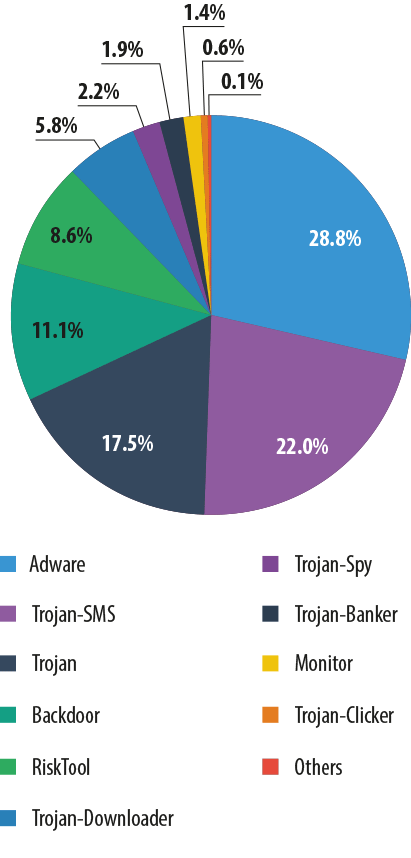

The distribution of mobile threats by type

The distribution of mobile threats by type, Q1 2014

During the first three months of 2014, the number one mobile threat turned out to be Adware, the only function of which is to persistently display advertisements. This type of malware is especially common in China.

After a long time in the lead, SMS Trojans were knocked down to second place after their share fell from 34% to 22%. However, this category of malware still leads among the Top 20 most frequently detected mobile threats.

Top 20 mobile threats

| Name | % of all attacks | |

| 1 | Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Stealer.a | 22.77% |

| 2 | RiskTool.AndroidOS.MimobSMS.a | 11.54% |

| 3 | Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.OpFake.bo | 11.30% |

| 4 | RiskTool.AndroidOS.Mobogen.a | 10.50% |

| 5 | DangerousObject.Multi.Generic | 9.83% |

| 6 | Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.FakeInst.a | 9.78% |

| 7 | Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.OpFake.a | 7.51% |

| 8 | Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Erop.a | 7.09% |

| 9 | Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Agent.u | 6.45% |

| 10 | Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.FakeInst.ei | 5.69% |

| 11 | Backdoor.AndroidOS.Fobus.a | 5.30% |

| 12 | Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.FakeInst.ff | 4.58% |

| 13 | Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Faketoken.a | 4.48% |

| 14 | AdWare.AndroidOS.Ganlet.a | 3.53% |

| 15 | Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Agent.ao | 2.75% |

| 16 | AdWare.AndroidOS.Viser.a | 2.31% |

| 17 | Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Agent.dr | 2.30% |

| 18 | Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Agent.fk | 2.25% |

| 19 | RiskTool.AndroidOS.SMSreg.dd | 2.12% |

| 20 | RiskTool.AndroidOS.SMSreg.eh | 1.87% |

New modifications of Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Stealer.a were a major factor in the surge in new mobile threats. There’s nothing particularly special about this threat; it features standard SMS Trojan functions, but it is still first in the Top 20 most frequently detected mobile threats.

It makes sense that last year’s leaders — Opfake.bo and Fakeinst.a — are still firmly holding on to their positions and continue to be major players in attacks against mobile user devices, flooding them with endless waves of new malicious installers.

Incidentally, Kaspersky Lab’s Top 20 most frequently detected mobile threats now includes the Faketoken banking Trojan for the first time (13th place).

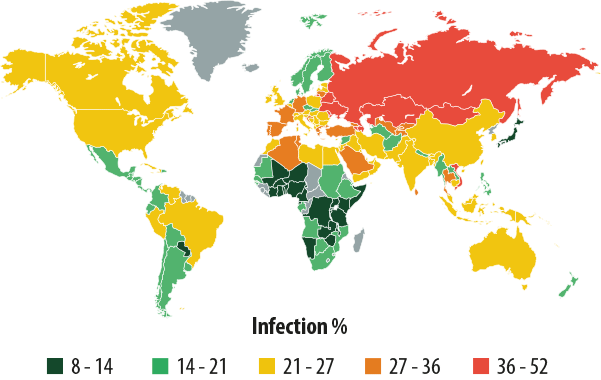

Threats around the world

Countries where users face the greatest risk of mobile malware infection, Q1 2014 (the percentage of all attacked unique users)

Top 10 most frequently targeted countries:

| Name | % of all attacks | |

| 1 | Russia | 48.90% |

| 2 | India | 5.23% |

| 3 | Kazakhstan | 4.55% |

| 4 | Ukraine | 3.27% |

| 5 | UK | 2.79% |

| 6 | Germany | 2.70% |

| 7 | Vietnam | 2.44% |

| 8 | Malaysia | 1.79% |

| 9 | Spain | 1.58% |

| 10 | Poland | 1.54% |

Statistics

All the statistics used in this report were obtained from the cloud-based Kaspersky Security Network(KSN). The statistics were collected from KSN users who consented to share their local data. Millions of users of Kaspersky Lab products in 213 countries take part in the global information exchange on malicious activity.

Online threats (attacks via the Web)

The statistics in this section were derived from web antivirus components which protect users when malicious code attempts to download from a malicious/infected website. Malicious websites are deliberately created by malicious users; infected sites can be those with user-contributed content (such as forums) as well as legitimate resources that have been hacked.

The Top 20 malicious objects detected online

In the first quarter of 2014, Kaspersky Lab’s web antivirus detected 29 122 849 unique malicious objects: scripts, exploits, executable files, etc.

We identified the 20 most active malicious programs which were involved in online attacks launched against users’ computers. These 20 accounted for 99.8% of all attacks on the Internet.

| Name | % of all attacks | |

| 1 | Malicious URL | 81.73% |

| 2 | Trojan.Script.Generic | 8.54% |

| 3 | AdWare.Win32.BetterSurf.b | 2.29% |

| 4 | Trojan-Downloader.Script.Generic | 1.29% |

| 5 | Trojan.Script.Iframer | 1.21% |

| 6 | AdWare.Win32.MegaSearch.am | 0.88% |

| 7 | Trojan.Win32.AntiFW.b | 0.79% |

| 8 | AdWare.Win32.Agent.ahbx | 0.52% |

| 9 | AdWare.Win32.Agent.aiyc | 0.48% |

| 10 | Trojan.Win32.Generic | 0.34% |

| 11 | AdWare.Win32.Yotoon.heur | 0.28% |

| 12 | Trojan.Win32.Agent.aduro | 0.23% |

| 13 | Adware.Win32.Amonetize.heur | 0.21% |

| 14 | Trojan-Downloader.Win32.Generic | 0.21% |

| 15 | Trojan-Clicker.JS.FbLiker.k | 0.18% |

| 16 | Trojan.JS.Iframe.ahk | 0.13% |

| 17 | AdWare.Win32.Agent.aiwa | 0.13% |

| 18 | Exploit.Script.Blocker | 0.12% |

| 19 | AdWare.MSIL.DomaIQ.pef | 0.12% |

| 20 | Exploit.Script.Generic | 0.10% |

* These statistics represent detection verdicts of the web antivirus module. Information was provided by the users of Kaspersky Lab products who consented to share their local data.

** The percentage of all web attacks recorded on the computers of unique users.

As is often the case, the Top 20 mostly includes verdicts assigned to objects used in drive-by attacks and to adware programs. The number of positions occupied by adware verdicts rose from seven to nine in the first quarter of 2014.

Of all the malicious programs in this ranking, Trojan.Win32.Agent.aduro in twelfth place is worth a special mention. This program spreads from websites that prompt the user to download a browser plug-in to assist online shopping.

If the user clicks the “Download” button, Trojan.Win32.Agent.aduro attempts to download to the user’s computer. The Trojan’s goal is to download the ad plug-in as well as a program for mining the crypto-currency Litecoin. Once successfully infected, the user’s computer will be used by cybercriminals to generate this crypto-currency, which will go straight into their wallets.

Also of interest is the malicious script Trojan-Clicker.JS.FbLiker.k in fifteenth place in the Top 20. It is mostly present on Vietnamese sites offering various types of entertainment and web resources that offer films and software for download. When a user visits such a site, the script imitates the user clicking on the “Like” button on a page in Facebook. After this, the Facebook page may be displayed as “liked” in the user’s news feed and in the user’s profile. A huge number of “likes” for a certain page alters its search results in Facebook.

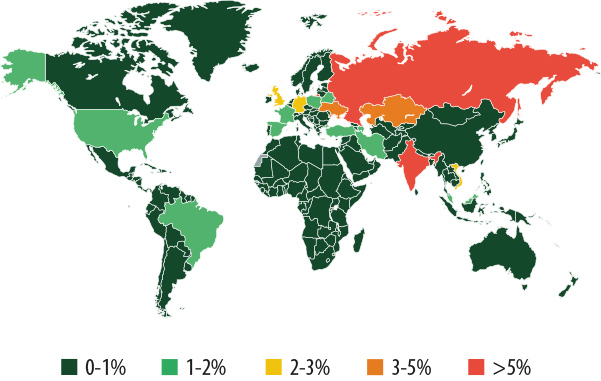

Countries where online resources are seeded with malware: Top 10

The following stats are based on the physical location of the online resources, which were used in attacks and blocked by antivirus components (web pages containing redirects to exploits, sites containing exploits and other malware, botnet command centers, etc.). Any unique host might become a source of one or more web attacks.

In order to determine the geographical source of web-based attacks, a method was used by which domain names are matched up against actual domain IP addresses, and then the geographical location of a specific IP address (GEOIP) is established.

In Q1 2014, Kaspersky Lab solutions blocked 353 216 351 attacks launched from web resources located in various countries around the world. 83.4% of the online resources used to spread malicious programs are located in 10 countries.This is 0.3 percentage points less than in Q4 2013.

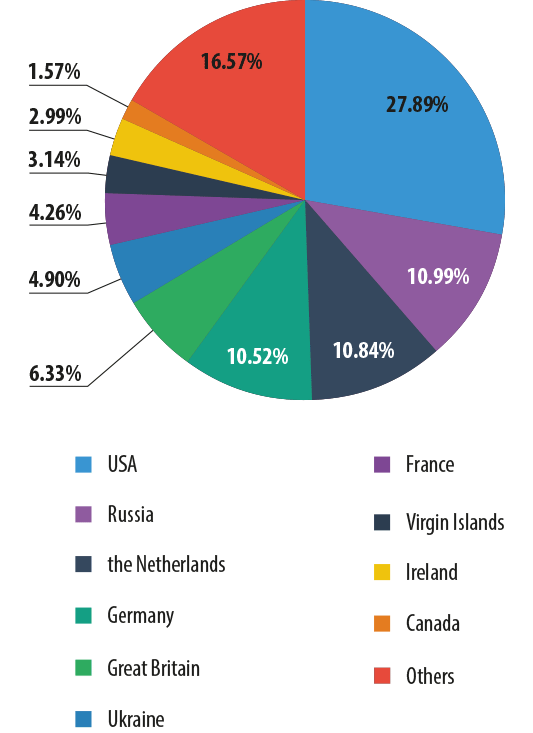

The distribution of online resources seeded with malicious programs in Q1 2014

This ranking has undergone only minor changes in recent months. Note that 39% of all web attacks blocked by Kaspersky Lab products were launched using malicious web resources located in the US and Russia.

Countries where users face the greatest risk of online infection

In order to assess in which countries users face cyber threats most often, we calculated how often Kaspersky users encountered detection verdicts on their machines in each country. The resulting data characterizes the risk of infection to which computers are exposed in different countries across the globe, providing an indicator of the aggressiveness of the environment in which computers work in different countries.

| Country* | % of unique users** | |

| 1 | Vietnam | 51.44% |

| 2 | Russia | 49.38% |

| 3 | Kazakhstan | 47.56% |

| 4 | Armenia | 45.21% |

| 5 | Mongolia | 44.74% |

| 6 | Ukraine | 43.63% |

| 7 | Azerbaijan | 42.64% |

| 8 | Belarus | 39.40% |

| 9 | Moldova | 38.04% |

| 10 | Kyrgyzstan | 35.87% |

| 11 | Tajikistan | 33.20% |

| 12 | Georgia | 32.38% |

| 13 | Croatia | 31.85% |

| 14 | Qatar | 31.65% |

| 15 | Algeria | 31.44% |

| 16 | Turkey | 31.31% |

| 17 | Lithuania | 30.80% |

| 18 | Greece | 30.65% |

| 19 | Uzbekistan | 30.53% |

| 20 | Spain | 30.47% |

These statistics are based on the detection verdicts returned by the web antivirus module, received from users of Kaspersky Lab products who have consented to provide their statistical data.

*We excluded those countries in which the number of Kaspersky Lab product users is relatively small (less than 10,000).

** Unique users whose computers have been targeted by web attacks as a percentage of all unique users of Kaspersky Lab products in the country.

Q1 2014 saw a change of leader in this ranking: Vietnam, where 51.4% of users faced web-borne attacks, is now in first place. Mongolia was the newcomer to this list, coming straight in at fifth with 44.7% of attacked users. The remaining positions in the top 10 are still occupied by Russia and the former CIS countries.

The countries with the safest online surfing environments are Singapore (10.5%), Japan (13.2%), Sweden (14.5%), South Africa (15.6%), Taiwan (16.1%), Denmark(16.4%), Finland (16.8%), the Netherlands (17.7%), and Norway (19.4%).

An average of 33.2% of user computers connected to the Internet were subjected to at least one web attack during the past three months.

Local threats

Local infection statistics for user computers are a very important indicator. This data points to threats that have penetrated a computer system through something other than the Internet, email, or network ports.

This section contains an analysis of the statistical data obtained based on the operation of the antivirus which scans files on the hard drive at the moment they are created or accessed, and the results of scanning various removable data storages.

In Q1 2014, Kaspersky Lab’s antivirus solutions successfully blocked 645 809 230 malware attacks on users’ computers. In these incidents, a total of 135 227 372 unique malicious and potentially unwanted objects were detected.

The Top 20 malicious objects detected on user computers

| Rank | Name | % of unique attacked users* |

| 1 | DangerousObject.Multi.Generic | 20.37% |

| 2 | Trojan.Win32.Generic | 18.35% |

| 3 | AdWare.Win32.Agent.ahbx | 12.29% |

| 4 | Trojan.Win32.AutoRun.gen | 7.38% |

| 5 | AdWare.Win32.BetterSurf.b | 6.67% |

| 6 | Adware.Win32.Amonetize.heur | 5.87% |

| 7 | Virus.Win32.Sality.gen | 5.78% |

| 8 | Worm.VBS.Dinihou.r | 5.36% |

| 9 | AdWare.Win32.Yotoon.heur | 5.02% |

| 10 | Trojan-Dropper.Win32.Agent.jkcd | 4.94% |

| 11 | Worm.Win32.Debris.a | 3.40% |

| 12 | Trojan.Win32.Starter.lgb | 3.32% |

| 13 | Exploit.Java.Generic | 3.00% |

| 14 | AdWare.Win32.Skyli.a | 2.80% |

| 15 | Trojan.Win32.AntiFW.b | 2.38% |

| 16 | Virus.Win32.Nimnul.a | 2.23% |

| 17 | Trojan.WinLNK.Runner.ea | 2.22% |

| 18 | AdWare.Win32.DelBar.a | 2.21% |

| 19 | AdWare.Win32.BrainInst.heur | 2.11% |

| 20 | Worm.Script.Generic | 2.06% |

These statistics are compiled from malware detection verdicts generated by the on-access and on-demand scanner modules on the computers of those users running Kaspersky Lab products that have consented to submit their statistical data.

* The proportion of individual users on whose computers the antivirus module detected these objects as a percentage of all individual users of Kaspersky Lab products on whose computers a malicious program was detected.

This ranking usually includes verdicts given to adware programs, worms spreading on removable media, and viruses.

The proportion of viruses in this Top 20 continues to fall slowly but steadily. In Q1 2014, viruses were represented by the verdicts Virus.Win32.Sality.gen and Virus.Win32.Nimnul.a, with a total share of 8%. In Q4 2013, that number was 9.1%.

The worm Worm.VBS.Dinihou.r in eighth place is a VBS script; it emerged late last year, and this is the first time it has made it to this ranking. Spam is one of the ways this worm spreads. The worm delivers the broad functionality of a full-fledged backdoor, ranging from the launch of a command line to the uploading of a specified file to a server. It also infects USB storage media connected to the victim computer.

Countries where users face the highest risk of local infection

| Rank | Country* | % of unique users** |

| 1 | Vietnam | 60.30% |

| 2 | Mongolia | 56.65% |

| 3 | Nepal | 54.42% |

| 4 | Algeria | 54.38% |

| 5 | Yemen | 53.76% |

| 6 | Bangladesh | 53.63% |

| 7 | Egypt | 51.30% |

| 8 | Iraq | 50.95% |

| 9 | Afghanistan | 50.86% |

| 10 | Pakistan | 49.79% |

| 11 | India | 49.02% |

| 12 | Sudan | 48.76% |

| 13 | Tunisia | 48.47% |

| 14 | Djibouti | 48.27% |

| 15 | Laos | 47.40% |

| 16 | Syria | 46.94% |

| 17 | Myanmar | 46.92% |

| 18 | Cambodia | 46.91% |

| 19 | Morocco | 46.01% |

| 20 | Indonesia | 45.61% |

These statistics are based on the detection verdicts returned by the antivirus module, received from users of Kaspersky Lab products who have consented to provide their statistical data. The data includes detections of malicious programs located on users’ computers or on removable media connected to the computers, such as flash drives, camera and phone memory cards, or external hard drives.

* When calculating, we excluded countries where there are fewer than 10,000 Kaspersky Lab users.

**The percentage of unique users in the country with computers that blocked local threats as a percentage of all unique users of Kaspersky Lab products.

The Top 20 in this category continues to be dominated by countries in Africa, the Middle East, and South East Asia. Vietnam ranks first, as was the case in Q4 2013, while Mongolia remains in second. Nepal moved up one place to third, while Bangladesh fell three places to sixth in Q4 2014. Morocco is a new entry in this ranking.

The safest countries in terms of local infection risks are: Japan (12.6%), Sweden (15%), Finland (15.3%), Denmark (15.4%), Singapore (18.2%), the Netherlands (19.1%), and the Czech Republic (19.5%).

An average of 34.7% of users’ computers were subjected to at least one local threat during the past three months.

IT threat evolution Q1 2014