Summary

Nowadays technology helps the development of hardware and software tools to record and analyze different aspects of our lives. This opens up new ways of staying aware of lifestyle and aiming to improve our health and fitness. One of the big trends in this sphere are fitness trackers such as smartbands, which, in the most popular current format, are bundles consisting of a hardware device we carry on our wrist and a mobile phone application to control the device and gain insights into the recorded data. We’re entrusting these gadgets with very personal and sensitive data about ourselves and letting them into dive into our very inmost self. This poses big questions for us as a security company:

- What kind of data is being collected

- What are the risks and where are they?

- What other parties might be interested in getting hold of this information, what’s the potential result?

- How can users help to protect their data?

Tracking devices and their corresponding mobile applications from three leading vendors were inspected in this report to shed some light on the current state of security and privacy of wearable fitness trackers.

What is it all about?

The quantified self, smartbands and what people want to achieve

We regularly measure aspects of our daily lives because we feel we have to, because it is human nature to want to stay safe. We typically set our goals for certain points in time and regularly check how well or badly we’re performing.

Things we often measure:

- Business: financial goals, project plans, salary

- Health: weight, height, eyesight, body mass index

- Sports: heartbeat, distance covered and altitude gain while cycling or running, average speed

But a movement known as ‘quantified self’ wants more. It wants to go beyond and off the beaten tracks. This movement has been around for years and people are getting together all over the world to exchange information, discuss their experiences and form a culture of self-tracking. They are searching for a healthier, more fulfilling life by measuring things in their daily routines that have been overlooked by traditional measuring schemes.

The healthy living angle of this is attracting a lot of attention these days. Most people work in offices and they only get exercise as they commute, go shopping or walk to the coffee machine. More and more people work from home and use online store to get the things they need delivered to them, so there is far less need to actually leave the house. At the same time people are more aware of their bodies than – both in terms of health and an attractive appearance.

There are several ways of measuring how healthy, fit and active we are. Heart beat monitors help us control our exercise and get hard facts about our condition. Speedometers help cyclists measuring the distance covered, what altitude gain they achieved and their average speed. But all these tools are limited. They are taken off after exercising so other everyday activities like walking or working aren’t recorded. If we use multiple devices the data remains isolated on each machine and is never correlated.

We entrust fitness trackers with our personal data and invite them into our innermost self

Tweet

This is where smartbands come into play. These devices are meant to be worn on our wrist all day and night to record our level of activity and also the time and quality of sleep. This generation of devices still records single snapshots, but the high frequency of recording sets makes it look like dynamic stream. It’s a bit like the difference between photography, which gathers single shots, and filming, which uses a constant stream of shots to create a dynamic image. By acquiring and correlating constant streams of different health related data, we get additional benefits and information about our daily life, some of which we may not have been aware of. This paints a more complete picture of our lifestyle.

Human nature also seeks improvement. Collecting and visualizing our activities in daily life and their effects on our body helps motivate us to set new high scores. With most smartband offerings, users can try to beat their own targets as well as competing with a broader audience of family members, friends, colleagues from work and other individuals from online training groups. These are connected by the eco-system of the vendor’s cloud network or by sharing information on social networks.

Smartbands – what they are and how they work

Basic smartbands are wristbands with mostly rubber surfaces to withstand shocks and moisture. The technological heart of the device is either firmly embedded into the body of the smartband or created in the form of a capsule, which can be placed into the band. The latter format allows the user to change the band if it gets damaged or worn out over time.

| Bluetooth module: | The main interface to upload collected data to a smartphone app and download new instructions, like vibration alarm at a defined time. |

| Vibration motor: | Just as on a smartphone, the motor lets the device vibrate to notify users of certain events like low battery or a pre-defined alarm. |

| Motion sensor: | Similar to the motion sensors in smartphones, the sensor monitors gyroscopic and accelerating movements. Vendor-defined algorithms then translate the movement into understandable units like steps. |

| Battery: | The battery of basic smartbands usually takes 35 – 70 mAH, a very low charge compared to smartphones, which take 2000 – 4000 mAH. Since there are far fewer components and they are usually more energy efficient, smartbands can keep running for one to two weeks, depending on how much data is being collected and how often power-consuming features are used. |

| Power/sync button: | Most smartbands can be operated with a single button to power on/off and sync or pair the device with the mobile phone. |

| Power jack: | To recharge the device’s battery via a USB adapter. |

| Display: | Basic smartbands offer a small LED or dot matrix display to show battery charge or essential information like time or the step count. |

Features

Different smartband offerings have similar features. They are all based on measuring the activity levels, longevity and quality of sleep, information on calorie balance and additional goodies.

Main features:

- step counter and approximate distance covered

- calorie consumption

- sleep recorder (duration and quality)

- self-defined fitness plan and a comparison with actual activity

More features:

- Nutrition intake and comparison with calories burnt from activity

- Friend list with texting functionality and comparison of activities

- Smart alarm for gentle recovery phase, based on measured stages of sleep

- Stopwatch

- Training diagrams

- Third party extensions, if offered

A closer look at the whole system

What data is collected by these devices?

The fitness trackers examined in this paper offer very similar feature sets and there is a consensus among the vendors about the data that is collected by the apps.

Required:

- Name (or nickname)

- Birth date (or just birth year)

- Height

- Weight

- Gender

- E-mail address

- Password for account

Optional:

- Country

- Training plan

- Weight goal

- Training goals (steps per day, hours of sleep)

- Nutrition plan

- Photo

- Mood

- Friends using the same fitness tracker

- . . .

The apps automatically show the correct localization, taken from the active settings on the mobile phone. Units for weight and height can be adjusted, enabling users to choose between imperial and metric systems, but is initially pre-set according to the mobile phone’s localization setting.

Some fitness trackers allow users to control what they share on their friend list, but not with the cloud service.

Collecting and processing the information

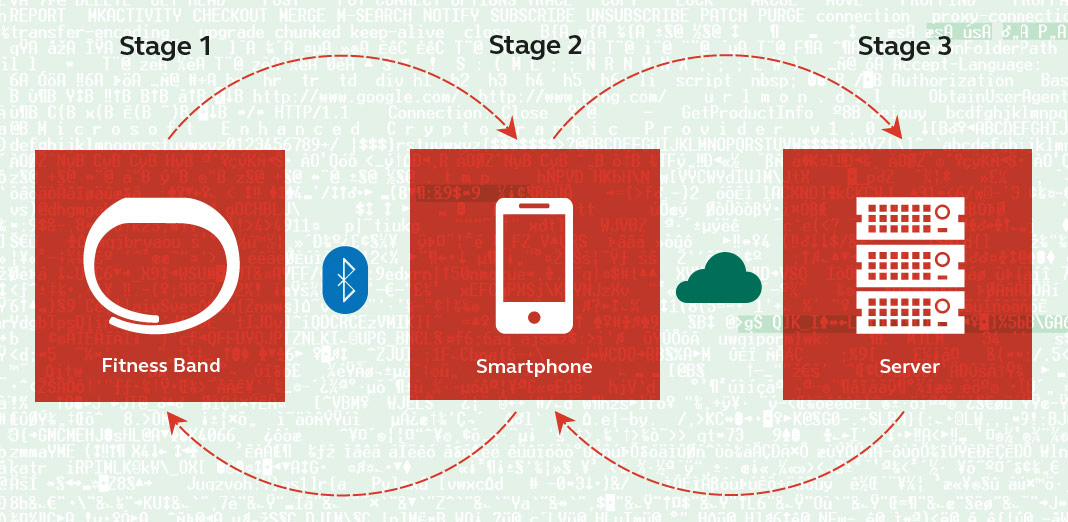

The data acquisition and processing is done in a chain comprising the smartband itself, a smartphone (usually Android or iOS based) or computer (running on Windows or OSX), the corresponding application to process the data and the vendor’s cloud service to provide deeper insights and store historical data. In order to synchronize the individual components the system uses Bluetooth and the Internet (via 3G/4G, Wi-Fi or wired connection).

The continuous synchronization between the tracking device and mobile phone requires a steady Bluetooth connection. This can have a considerable impact on the battery time of the phone. However the tracker is able to store data without synchronization for anywhere between two and 30 days, depending on the device and the amount of information recorded. Most vendors recommend keeping Bluetooth enabled at all times to ensure the best user experience.

Stage 1: Record data and short term storage

Stage 2: Process and correlate data, send instructions to control smartband

Stage 3: long time storage, web based interface for better viewing and deeper investigation

Smartbands are currently in a state of transition. The popularity of the product is prompting new varieties to come to market, and demand is growing for different formats. The type of smartband we know at present will be known as basic smartbands; future generations will offer additional innate processing power instead of merely collecting data. Some companies already have plans for products like combined smartwatches and activity sensors including heart beat monitors.

The daily traffic for cloud synchronization is around 1 -2 MB per day, depending on the model, level of activity and which features are used. Users without mobile Internet flat rates should consider performing this task via Wi-Fi only.

Possible vectors of compromise

In general, the more devices and data transmissions between them are needed in a system, the greater the possibility of compromising the chain. Most smartband environments use the above-mentioned scheme. Other types of fitness trackers cut out the smartband and record the data on the smartphone itself or don’t offer a cloud service. For these types some attack vectors are not applicable.

Synchronization between tracking device and mobile phone

The smartband is meant to be worn day and night; however, their owners may well take them off from time to time. Therefore it could be left unattended for a while and anyone with a compatible device and the appropriate app – which is usually free of charge – could theoretically synch with the device and gain access to the data it records. That data could potentially be delivered to a rogue smartphone whenever it is range.

The information from smartbands and fitness trackers includes highly personal details about an individual. These could be used against the user for:

- Blackmail

- Naming and shaming on the Internet

Other than that, thieves might also be interested in the victim’s training schedule since it could alert them to times when the flat or home is left empty.

The good news is that each of the smartbands we reviewed features some kind of integrated protection against this risk. The apps signed out from the phone and notified the owner that the smartband had been disconnected. The only information available to a rogue user was the data collected that day, or since the last synchronization. However, since only a small fraction of today’s smartband offerings were tested, this attack vector might still apply to other devices.

The bad news is, the protection mechanisms can be susceptible to attacks, as my colleague Roman Unuchek proved in his blog post “How I hacked my smart bracelet“. He was able to compromise the authentication process and thereby read the tracker’s recorded data as well as executing code on it. According to his research, sometimes it is even possible to hijack the device without the owner even knowing.

Synchronization between the mobile phone and the server

The synchronization between the smartphone apps and the cloud servers is a neuralgic point, since the data stream comprises both the data gathered and the credentials to access the user’s account. When smartbands hit the market some years back, some curious security researchers dipped into the traffic; a great uproar soon followed as it emerged that many vendors had no encryption whatsoever in this process, meaning all data was transmitted in clear text, perfectly readable for anyone who came upon it.

The synchronization between the smartphone apps and the cloud servers is a neuralgic point

Tweet

Fortunately, all the vendors of smartbands tested in this paper did their homework, since all of them incorporated a form encryption in their apps (TLS/SSL). This way, it is no longer simple to sniff traffic over Wi-Fi.

Compromising the mobile phone

Mobile malware has been a hot topic in recent years, with the number of new samples increasing in an almost exponential fashion. In the period from 2004-13 Kaspersky Lab analyzed almost 200,000 mobile malware code samples. In 2014 alone there was an additional stream of 295,539 samples. However, this doesn’t give the whole picture. These code samples are re-used and re-packaged: in 2014 we saw 4,643,582 mobile malware installation packs (on top of the 10,000,000 installation packs that had been seen in the period 2004-13). The number of mobile malware attacks per month increased tenfold – from 69,000 per month in August 2013 to 644,000 in March 2014.

All the vendors of smartbands tested in this paper incorporated a form encryption in their apps (TLS/SSL)

Tweet

The typical modus operandi of cybercriminals is to use legitimate apps or app names as a vehicle to spread their malicious creations – mainly on third party app sites. One mobile malware sample is usually packaged under just one installer package, but sometimes even a hundred could be used to increase the leverage and therefore spread it among different user groups. Malicious fake apps for smartbands, asking the user for the login credentials and thereby hijacking the account and all the information on it are entirely plausible. In combination with other data from the compromised phone, such as GPS coordinates of check-in features from social networking apps, this would pretty much by ‘game over’.

However, the daily life of a smartphone poses a far higher risk. These devices are especially prone to getting lost. For example the London Underground reported more than 15,000 phones were lost in its trains in 2013 [1]. Without a lock screen in place, all information is visible to anyone who finds a smartphone, and that includes the information stored in fitness trackers. None of the smartband apps tested for this report offered the opportunity of locking the app with separate pin.

Compromising the cloud service

Aside from targeting single devices and users, attackers could also aim for the cloud service itself and seek access to records from all users.

Sometimes not even sophisticated hacking skills are needed, as one leading smartband vendor’s user portal proved in 2011. All the user profiles were indexed by a popular search engine, making it easy to simply search the Internet for specific expressions that were only found in these profiles. Back then, users had the option to make their profile “private” but they were set to “public” by default. In addition, users could manually enter descriptions for their activities and certain timeframes, e.g. to find out what is most helpful when trying to lose weight. This meant that even the most private kind of “activity” was publically visible for everyone to see, together with information on longevity and how many calories were burned [2]. The vendor subsequently took action to prevent this. This case highlights how easily information and privacy leaks can result from misconfiguration and/or lax privacy policies.

Tracker’s users have the option to make their profile “private”, but they’re set to public by default

Tweet

One smartband vendor’s API allows users to access their data via a user ID and the serial number of the smartband, as well as the more traditional username-and-password combo. However, if a third party has the required information, the essential data can be downloaded without the user’s knowledge.

In 2014 we saw numerous class A exploits like Shellshock or Heartbleed targeting web servers. These attacks were performed in a scripted fashion to IP addresses throughout the world by numerous gangs. It is still not clear how much data was gathered in these mega breaches, nor what the overall effect will be. Cloud services are not exempt from attacks like this and are seen as a lucrative target. It’s only a matter of time until the next big exploit is found.

Other potential traps

According to research performed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, one smartband is notorious for scanning the user’s environment for other Bluetooth-enabled devices, like computers, mobiles, other smartbands etc. As well as gathering the addresses of these devices, it also passes them to the vendor’s servers via the smartband’s phone application. This way, the vendor is potentially able to create a profile of each user’s infrastructure environment.

In addition, the smartband itself uses BTLE (Bluetooth Low Energy), which makes it possible to change the device’s address from time to time to avoid tracking the wearer. However, the vendor chose not to use this feature.

Fake smartband apps, asking for login credentials, are entirely plausible

Tweet

One tested smartband app invited the user to install additional apps from third parties to integrate and associate the collected data for deeper insights into the state of the users’ health and activity. Possible extensions include correlating the standard data with GPS recording during workouts, dedicated apps for further visualizations, apps offering additional weight control related models, apps encouraging the user to eat more healthily (e.g. more fruit) and even offering financial incentives if all goals have been completed, paid by users who didn’t meet their own targets.

If integrated, user automatically agrees to share this kind of data with the supplier.

The last potential trap has been a classic for decades. People tend to reuse their passwords over and over out of convenience. Most people have a main e-mail address, which also serves as a username on many websites and services. Now if one these accounts is compromised due to a server side breach (and we read of these breaches almost every week) or a malware infection stealing the login credentials on one of the machines, this means the other accounts using the same password are in massive danger. It is widely known that cybercriminals try these credentials on many of the big web portals like online shops, online payment systems, social networks and anything else that might turn a cash profit in the digital underground.

Commercial models around smartbands, fitness trackers and other gadgets

The flood of personal information, gathered by millions of users of smartbands and other wearables, whets the appetite of others as well as cybercriminals.

This kind of information is highly valuable to companies and institutions in different sectors.

Insurance companies

Insurance companies are based around risk estimation. To do this effectively, data has to be collected and evaluated to calculate the appropriate premiums from customers. The better the data, the better companies can manage their business. This is where fitness trackers come into play. What data could possibly be better than actual data streaming in real time from the customers themselves? At the time of writing some insurance companies are launching special programs for customers who are willing to share the information gathered from their fitness trackers. In return, financial incentives are offered to customers who prove to have a healthy lifestyle, as well as vouchers for travel and additional fitness courses [4].

None of the smartband apps tested offered the opportunity to lock the app with a PIN

Tweet

What could possibly go wrong? This scheme could potentially backfire. Imagine a keen fitness enthusiast who is also not averse to extreme sports. What if the tracking device and smartphone regularly transmit data about driving to an infamously dangerous mountain bike downhill track? GPS data sent from the smartphone and additional “step” count, coming from the rocks beneath the tire while riding at 40 kilometers per hour down the hill prove that someone didn’t just go there to be a spectator, and this might displease the insurer. It could result in increased insurance costs based on the customer’s allegedly higher risks. Depending on the legal situation in different regions in the world there’s also a chance that insurance companies would refuse to insure high-risk clients because of the data recorded by their tracking devices.

Apart from fitness trackers, there are other gadgets and apps being developed to optimize the quantified self, like toothbrushes with integrated sensors to monitor the motion of the brush in three dimensions and a Bluetooth uplink to a dedicated smartphone application [5]. The app includes mini games to teach, motivate and reward people, especially children. It also tracks how often the teeth are being brushed and for how long. Again, insurers (dental insurance in particular) would be pleased to get their hands on this data.

Employers

Companies also discovered fitness trackers for their employees. There are already examples of employers offering these devices to their workforce to measure their health and motivate them towards a healthier lifestyle. British Petroleum (BP) introduced a “wellness program”, in which employees are given points for reaching certain targets and incentives like health care premiums are offered [6]. Employees thinking about joining such program should thoroughly check the privacy policy and consider what potential consequences it might have.

Advertisement industry

There are almost no mobile apps on the market that offer users the option of disabling the flow of data into the cloud. As a result vendors quickly learn about your habits and your state of health. Depending on privacy policies, this enables them to tailor advertising based on the user’s information and activity. Even within a general interest or activity, advertisements can focus on specific user groups: for example beginners could be offered running shoes and basic sportswear, whereas advanced athletes are shown advertisements for more expensive equipment, LED headlamps for night-time work outs or special sports nutrition. All offers can be adjusted for your local currency and targeted at the right gender and approximate size according to the weight and height set in the app.

Other parties

After the earthquake in Northern California the smartband vendor Jawbone published a diagram on their blog that showed the impact on sleep the event had in different areas around the epicenter [7]. All data was collected from thousands of customers, aggregated and presented in an anonymized form. The data enabled Jawbone to come up with a new format to show the actual impact of the earthquake on people rather than approximate seismographic ratings for surrounding areas. The graph appeared on many news sites around the globe.

Personal information gathered by millions of smartband users whets the appetite of cybercriminals

Tweet

The year 2014 marked the first time that data recordings from smartbands were used in court, opening the way for future cases. In this case the woman in question freely provided her data to prove that her injuries from a car accident limited her activities. Her information was compared with other women of her age using a third party [8]. In this case the use of data was not controversial – the woman provided her data freely to prove her point. It is important for smartband users to remember that vendors usually include a clause in their user agreements and privacy policies to make it clear that they can disclose information in response to a court order. It is also important to understand that the gathered data won’t necessarily be kept in the country where it was recorded, but could also be used in foreign countries with a different jurisdiction.

According to researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem it is possible identify individuals by the distinct shake of their GoPro cameras, worn on the head, from a sample of only a few seconds [9]. This raises the question whether algorithms along these lines could allow individual smartband users to be identified by their activity and sleep patterns.

Is there a more private way to keep track of your fitness?

More private alternatives (read: self-sufficient) to smartbands include pedometers and fitness tracker apps. Both options can act as single device systems and thereby cut off potential vectors of compromise that affect common smartband systems.

Fitness tracker apps commonly use an internal gyroscopic sensor and accelerometer to keep track of activities. Tracker apps lack the sensors to measure people’s sleep and also do without some other features of smart devices. Dedicated step counter devices, called pedometers, offer a similar feature set, but are easy on the smartphones’ battery. Some offerings can be synced with a smartphone, others are completely self-sufficient. They can be carried it in a pocket or clipped onto your belt.

Advice for users of smartbands

To minimize the risks of your data being compromised, there are several pieces of advice to follow. Many of them apply not only to smartband users but to anyone using apps that store personal information:

- Only use features you really need and avoid giving out any personal information that you would not want to store in the cloud

- Use a strong and unique password for each account

- Lock the home screen on your smartphone and use access protection

- Encrypt your phone if possible

- Use security solutions for all devices, if available

- Read the license agreements of applications and pay close attention to how personal information might be used by the service

- Install app and operating system updates when available

- Uninstall/Delete applications that are not needed anymore

- Turn off the Bluetooth and location services on phones when not needed (this also preserves battery time)

Conclusion

Smartbands have been around for almost a decade by now, so they are almost senior citizens compared with many gadgets. While some old security issues like absence of encryption or public indexing of user profiles have been fixed, they show that security is still an afterthought for many companies. Security is also a process; vulnerabilities in drivers, protocols and the whole server ecosystem are found more and more frequently, vendors need to monitor vulnerabilities and the exploit landscape and quickly patch their software on both the client side (smartphone apps) and the server side (cloud service) to secure the customer data.

Security, though, depends on both makers and users alike. Everyone involved must understand the value and sensitivity of the user data collected by the fitness tracker. Normally when a breach involving personal data happens, data like names, mail addresses, birthdates, credit card information or passwords are affected. In this context, the information is even more personal. It contains health and body related data, including details that someone would normally confide only to a handful of very close people – or possibly even the doctor alone.

Smartband vendors are sitting on a goldmine of information that would be of great value to third parties in its anonymized form and even more attractive in a user-specific context. But if vendors decided to give out this data in either format (and risk losing their users’ trust), third parties need to be cautious about the data. After all, what is to stop users attaching a smartband to a hyperactive pet dog and using that to get preferential ‘active lifestyle’ rates from an insurance company?

Although smartbands are relatively old technology, they are still part of the breeding ground for devices and services that trade on quantifying ourselves. New kinds of devices are coming up, integrating old technology and combining them with new innovation. Gadgets like smartwatches and Google’s Glass are examples of how the future might shape up in this area.

Appendix: Resources

(1) More than 15,000 lost mobile phones on London Underground pose security risks

http://www.v3.co.uk/v3-uk/news/2318727/more-than-15-000-lost-mobile-phones-on-london-underground-pose-security-risks

(2) Dear Fitbit users, kudos on the 30 minute of vigorous sex activity last night

http://gizmodo.com/5817784/dear-fitbit-users-kudos-on-the-30-minutes-of-vigorous-sexual-activity-last-night

(3) Security Analysis of Wearable Fitness Devices (Fitbit)

https://courses.csail.mit.edu/6.857/2014/files/17-cyrbritt-webbhorn-specter-dmiao-hacking-fitbit.pdf

(4) Insurance company Generali wants to collect fitness data from customers (German)

http://www.heise.de/newsticker/meldung/Neue-Krankenversicherung-Generali-will-Fitnessdaten-von-Versicherten-sammeln-2461512.html

(5) Kolibree, Smart Tooth Brush

http://kolibree.com/en/

(6) Wearables at work mean big business, says Fitbit CEO

http://www.cnbc.com/id/101318809#

(7) How the Napa Earthquake Affected Bay Area Sleepers

https://jawbone.com/blog/napa-earthquake-effect-on-sleep/

(8) Fitbit Data now being used in the Court Room

http://www.forbes.com/sites/parmyolson/2014/11/16/fitbit-data-court-room-personal-injury-claim/

(9) Egocentric Video Biometrics

http://arxiv.org/abs/1411.7591

IoT Research – Smartbands