A major objective pursued by malware writers when developing malicious code is to make it start as early as possible, enabling it to make key modifications to the operating system’s code and system drivers, such as installing hooks, before the antivirus product’s components initialize. As a result, malware and anti-malware products play cat and mouse of sorts, since they operate at the same level: the operating system, system drivers and rootkits all operate in kernel mode.

Bootkits currently represent the most advanced technology available to cybercriminals. It enables malicious code to start before the operating system loads. The technology is implemented in numerous malicious programs.

We have written about bootkits (such as XPAJ and TDSS (TDL4)) several times. The latest bootkit-related publication so far describes scenarios of targeted attacks based on the bootkit technology as implemented in The Mask campaign. However, such papers are not released often and some experts may get the impression that bootkits, like file viruses, are ‘dead’, that Trusted Boot has done its job and that the threat is no longer relevant.

Nevertheless, bootkits do exist; they are in demand on the black market and are extensively used by cybercriminals for purposes which include conducting targeted attacks.

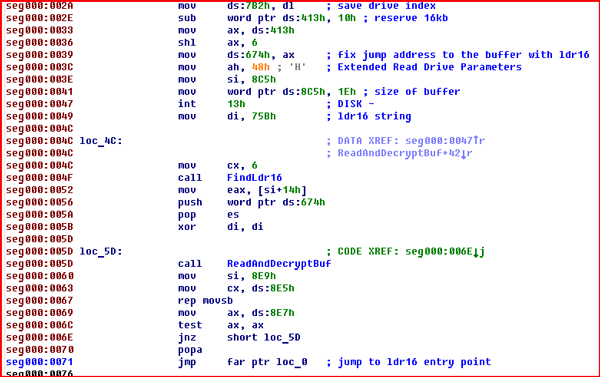

Fragment of TDSS loader code in MBR

Statistics

First, let’s have a look at KSN statistics. The table below represents a ranking of malicious programs that we detect as Rootkit.Boot.*, for the period from May 19, 2013 to May 19, 2014.

| Family | Users | Notifications |

| Rootkit.Boot.Cidox | 45797 | 60787 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Pihar | 25490 | 75320 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Harbinger | 19856 | 34427 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Sinowal | 18762 | 420549 |

| Rootkit.Boot.SST | 8590 | 73079 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Tdss | 5388 | 19071 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Backboot | 4344 | 9148 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Wistler | 4230 | 13014 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Qvod | 1189 | 1727 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Xpaj | 690 | 2483 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Mybios | 442 | 5073 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Plite | 422 | 648 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Trup | 300 | 7395 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Prothean | 217 | 1407 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Phanta | 167 | 5475 |

| Rootkit.Boot.GoodKit | 120 | 131 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Smitnyl | 100 | 3934 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Stoned | 69 | 96 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Geth | 60 | 166 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Nimnul | 53 | 84 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Niwa | 37 | 121 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Fisp | 35 | 344 |

| Rootkit.Boot.CPD | 25 | 39 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Lapka | 19 | 21 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Yurn | 8 | 18 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Aeon | 6 | 6 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Mebusta | 5 | 5 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Khnorr | 4 | 4 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Sawlam | 4 | 7 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Xkit | 4 | 20 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Clones | 1 | 1 |

| Rootkit.Boot.Finfish | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 136435 | 734601 |

Most bootkits are proactively detected using behavior-based technology as early as at the stage of their installation in the system. Alternatively, they can be detected the first time the antivirus product performs an automatic scan after system startup, resulting in the active infection removal procedure being launched. Note that the statistics shown above include only infected Master Boot Record detections. The figures also include data received from previously infected machines on which our antivirus solution was installed after the machines were infected.

It can be seen in the table above that derivatives of TDSS – Pihar and SST – are among the TOP 5 bootkits detected. The Harbinger bootkit, which ‘covers’ adware, is in the third position and Sinowal is in fourth place in the ranking. First place is occupied, with a considerable lead, by Rootkit.Boot.Cidox. Since Cidox has played a special role in bootkit evolution, we will discuss its story in greater detail.

Cidox: publicly available code

Cidox is offered as a supplement to other malicious programs and is used to protect the malware with which it is distributed. This means that the bootkit is not used to build its own botnet TDSS-style.

The initial versions of the malware were included in Kaspersky Lab antivirus databases three years ago, on June 28, 2011. Back then, Cidox was a breakthrough in malicious technology, because it was the first to infect VBR rather than MBR.

Cidox was used to protect the banking Trojan Carberp, among other malicious programs. When the Carberp source code was published, the bootkit’s source code was ‘leaked’ as well. As a result, Cidox re-enacted the story of the infamous ZeuS (Zbot) Trojan. While the ‘leak’ of ZeuS source code made it much easier to steal money from online banking systems, the publication of Cidox source code has meant that any more or less experienced programmer can have a go at writing malware which operates at the lowest level, before operating system startup.

Cidox is currently used to load and protect a variety of malware, including crimeware, blockers and malware designed to steal money in online banking systems.

Targeted attacks

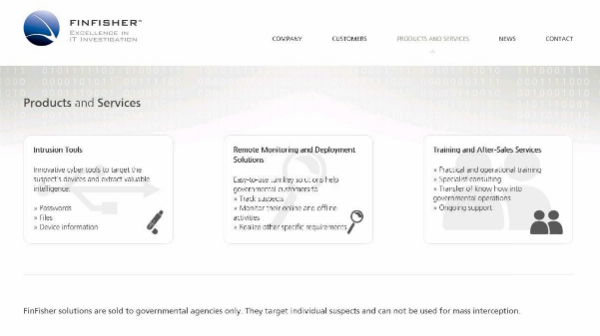

The Mask campaign mentioned above was not a unique case of bootkits being used in targeted attacks. A while ago, we wrote about HackingTeam, a company whose software (including bootkits) is used when conducting police operations in various countries around the globe. Another company, FinFisher, offers similar services, while the software developed by it also includes a bootkit – Rootkit.Boot.Finfish, which happens to be in last place on our ranking.

List of products and services from FinFisher’s official website

An analysis of products offered by FinFisher was presented in a Kaspersky Lab paper prepared for a Virus Bulletin conference. The presentation can be found on the VB website.

BIOS. A quest for new starting points

The never-ending struggle between antivirus solutions and malicious code is leading both the former and the latter to the next phase in their evolution. Malware writers have to search for new starting points, with the BIOS becoming one of these. However, things have hardly moved past test research, because mass modification of the BIOS is an ‘inconvenient’ operation for malware writers, which requires considerable effort to perform and can therefore be used only in highly targeted attacks.

What dreams may come

The classical BIOS system is now essentially a relict that is difficult to use and has numerous limitations. This was why a completely new unified modular interface, UEFI, was developed by the UEFI Forum consortium based on specifications initially provided by Intel.

What UEFI offers:

- Support for modern equipment.

- Modular architecture.

- EFI Byte Code – architecture and drivers that are independent of the CPU type (x86, x86-64, ARM/ARMv8).

- Various extensions for UEFI, which are loaded from different media, including portable devices.

- Development using a high-level programming language (a dialect of C).

- Secure Boot.

- Network booting.

We also recommend reading about the 10 most common misconceptions about UEFI.

The following operating systems support UEFI:

- Linux using elilo or a special version of the GRUB boot loader.

- FreeBSD.

- Apple Mac OS X for Intel-compatible systems (v10.4 and v10.5 provide partial support, while v10.8 provides complete support).

- Microsoft Windows, starting from Windows Server 2008 and Windows Vista SP1 x86-64. Microsoft Windows 8 supports UEFI, including 32 bit UEFI, as well as secure boot.

In short, what does UEFI offer? A simple, easy to understand, well-documented, unified and convenient method of development without resorting to 16-bit assembly programming.

From the viewpoint of an anti-malware solution, UEFI is a very good place to implement something like a rescue disk. First, the rescue disk’s code will run before the operating system and boot loader start; second, UEFI offers easy hard drive access, as well as more or less easy network access; third, a simple and easy-to-understand GUI can be created. Just what the doctor ordered when one has to deal with sophisticated and actively resisting threats such as bootkits.

From the viewpoint of malicious code developers, all of the above is also advantageous for a bootkit, enabling it to provide more reliable protection for malware. At least until firmware developers take care to implement proper protection.

However, before moving on to protection functionality, we would like to address one important issue. Equipment manufacturers develop their firmware themselves and make their own decisions regarding support for optional features offered by the UEFI specification. Such features include, first and foremost, protecting firmware in SPI Flash from modification and secure boot. In the case of UEFI, we have the classical problem of Convenience vs. Security.

Threats and protections mechanisms

It comes as no surprise that, as UEFI became universally implemented, it attracted the interest of independent researchers as a potential attack vector (one, two, three). The list of possible penetration points is quite extensive and includes compromising (injecting, replacing or infecting) OS boot loaders and EFI, compromising UEFI drivers, directly accessing SPI Flash from the operating system and many others. In the case of booting in UEFI+Legacy (CSM) mode, old methods of infecting the system used by bootkit developers remain effective. It is also quite obvious that if the pre-boot execution environment is compromised, all the Windows security mechanisms, such as Patch Guard, driver signature verification etc., are rendered useless.

The UEFI specification version 2.2 included a new secure boot protocol, which was to provide a secure pre-boot execution environment, as well as protection against malicious code being executed from potentially vulnerable points.

The secure boot protocol defines the process used to verify the modules being loaded, such as drivers, the OS boot loader and applications. These modules should be signed with a special key and the digital signature should be verified before loading a module. The keys used to verify modules should be stored in a dedicated database protected against penetration, such as a TPM. Keys can be added or modified using other keys, which provide a secure method of modifying the database itself.

Based on the above, implementation of the following security mechanisms by firmware and operating system developers can be regarded as optimal from the security viewpoint:

- Protecting SPI Flash against malicious modification. Disabling support for upgrading firmware from the operating system.

- Blocking access to critical UEFI sections, including most environment variables.

- Completely abandoning the use of CSM.

- Protecting the system volume containing UEFI drivers, boot loader and applications from malicious modification.

- Operating system and firmware developers should implement and enable Secure Boot (as well as the Trusted Boot mechanism implemented in Windows OS).

- Protecting the key storage from modification.

- Protecting the mechanism used to update the database in which keys are stored from spoofing and other types of attacks.

- Implementing protection against “Evil Maid” attacks, which involve physical access to the computer.

- Using the expertise accumulated by leading anti-malware companies and implementing anti-malware technologies at the firmware level.

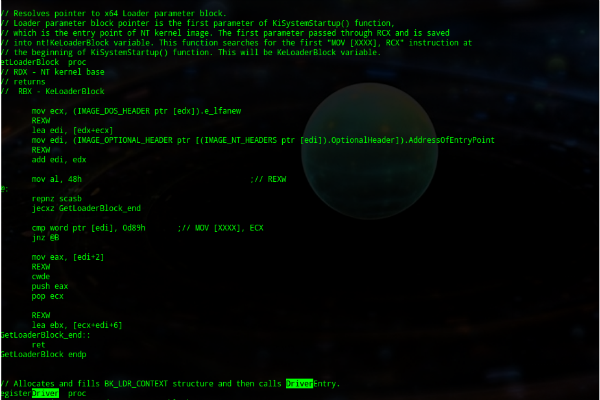

However, it should be kept in mind that as more advanced protection mechanisms are implemented, cybercriminals will come up with more advanced attacks against UEFI. The methods currently used are based on replacing the UEFI boot loader for the Windows 8 operating system. During its initialization, the malicious OS loader loads a replaced loader into memory, disables Patch Guard security mechanisms and driver signature verification using one method or another, sets the necessary hooks and passes control to the original loader code.

In the case of Mac OS using full-disk encryption, an original approach is used, which is based on implementing a simple UEFI keylogger to obtain the secret passphrase entered by the user on the keyboard to decrypt contents of the hard drive at system startup. In all other respects, the method based on replacing or infecting the system boot loader is applicable in this case, as well.

Conclusion

Bootkits have evolved from Proof-of-Concept development to mass distribution and have now effectively become open-source software. Launching malicious code from the Master Boot Record (MBR) or the Volume Boot Record (VBR) enables cybercriminals to control all the stages of OS startup. This type of infection has essentially become standard for malware writers. Its implementation is based on proven, well-researched technologies. Importantly, these technologies are available on a variety of resources in the form of source code. In the future, this may lead to a significant increase in the amount of malware based on these technologies, with only minor changes in individual programs’ logic of operation. We expect to see new modifications of TDSS and Cridex, which are already familiar to cybercriminals. We are also concerned that such malware might be used in other types of attacks perpetrated by cybercriminals, e.g., in systems which use Default Deny technologies.

Crucially, the state-of-the-art anti-malware technologies implemented in our products are successful in combating such infections. Since it is hard to predict now what specific methods of masking, blocking or resisting anti-malware products will be invented by cybercriminals in the near future, implementing anti-malware technologies at the firmware level, in combination with the protection mechanisms described above, will enable security solutions to neutralize rootkits and bootkits before malicious code is able to take control. In addition, incorporating an anti-malware module in UEFI will simplify the process of removing infection and the development of new methods for detecting newly-developed bootkits that use new, advanced masking techniques, as well as rootkits which interfere with the operation of the system or the anti-malware solution.

P.S. Special thanks from the authors to Vasily Berdnikov for his help in researching material for this paper.

Attacks before system startup

Suzie Haslinger

I have been attacked by a RAT that has corrupted by inserting or modifying code in the following: my Bios and set it to no flash, my memory (which shows more than is installed, among other things, my pci chipset, which has created 21 virtual devices, the IRQ tables are corrupt am on a server, my local machine is poorly constructed shell, attributes and permissions were changed, my files have been moved to the server, etc, etc,. The damage is incredible and has destroyed the motherboards even of six laptops. One defining feature is when viewing hidden devices in Device Manager, a long, long string of Upnp devices exist, presumable by the chipset, which has removed all device drives and added virtual PCI devices. I can find nothing on what this hack might be. It even corrupted a Linux boot disk (DVD) Id been using to get online (UBCD), which now has files corrupted as well. Seems to have re-written to the DVD. I am VERY computer savvy, running my own pc repair business, but this has put me out of business and simply freaked me out. Ive read enough dll files to know it goes through a particular MS SQL server, and there was a references to a tsure server, which I understand to be in Russia. Can you shed any light please???