In the field of information security, sandboxes are used to isolate an insecure external environment from a secure internal environment (or vice versa), to protect against the exploitation of vulnerabilities, and to analyze malicious code. At Kaspersky Lab, we have several sandboxes, including an Android sandbox. In this article, we will look at just one of them that was customized to serve the needs of a specific product and became the basis of Kaspersky Anti Targeted Attack Platform. This particular sandbox is an analysis system for Windows applications that helps automate the analysis and detection of malicious code, conduct research and promptly detect the latest types of attacks.

There are several ways of implementing a sandbox to perform dynamic analysis of malicious code. For example, the following methods can be used:

- Standard emulation, interception of functions in the user space and in the kernel space;

- Information from kernel callback functions and from various filter drivers;

- Hardware virtualization.

Combinations of these methods are also possible.

Practice has shown that implementation of full-fledged emulation is a costly affair as it requires continuous support and enhancements to the emulation of API functions, as well as increased attention to execution evasion and emulation detection techniques. Interceptors didn’t last too long either: malware learned to bypass them using relatively simple methods, ‘learning’ to identify if they are present and refusing to execute their malicious payload to avoid detection.

Methods to detect and bypass splicing have been known for years – it’s sufficient to check or trace the prologues of popular API functions or build your own prologues to bypass an interceptor (the latter is used by cryptors and packers). Moreover, splicing technology itself is fairly unstable in a multithreaded environment. It’s also obvious that in a user space the level of isolation of malicious code from interceptors is effectively zero, because the operating system itself is modified – something that is very conspicuous.

And that’s not all. In order to receive the results for the execution of an API function, it’s necessary to regain control after its execution, which is typically done by rewriting the return address. This mechanism has also proven unstable. However, the biggest headache came with the attempt to transfer this sort of mechanism to new operating systems.

Therefore, if a security solution vendor claims their sandbox uses splicing of API functions, takes events from the Windows kernel and is “amazing, unique, undetectable and produces near-100% results”, we recommend you avoid them like the plague. Some vendors may be perfectly happy with that sort of quality, but we definitely aren’t.

Having taken note of all the above facts (and a number of others), we have implemented our own sandbox based on hardware virtualization. At the current time this is an optimal solution in terms of balance between performance, extendibility and isolation.

A hypervisor provides a good degree of isolation of the guest virtual machine from the host by ensuring control over CPU and RAM. At the same time, modern processors have a minimal impact on performance when virtualization is used.

The infrastructure

The hardware for our sandbox has been acquired at different times over recent years, and is still being added to, so its infrastructure is rather diverse. Today, we have around 75 high-performance servers deployed, constituting four nodes in three data centers; in total, there are some 2500 vCPUs. We use a variety of hardware types, from M2 systems and blade servers to M5 systems running Intel Xeon E5, with support for the technologies we need. Up to 2000 virtual machines are running at any given time.

Up to four million objects per day are processed by the service at peak times, and around two million at off-peak times.

For Internet access within the sandbox, about 15 channels are used, the details of which we prefer not to disclose. Outgoing traffic from the node reaches 5 Gb/s at peak times and 2 Gb/sec at off-peak times.

The internal structure

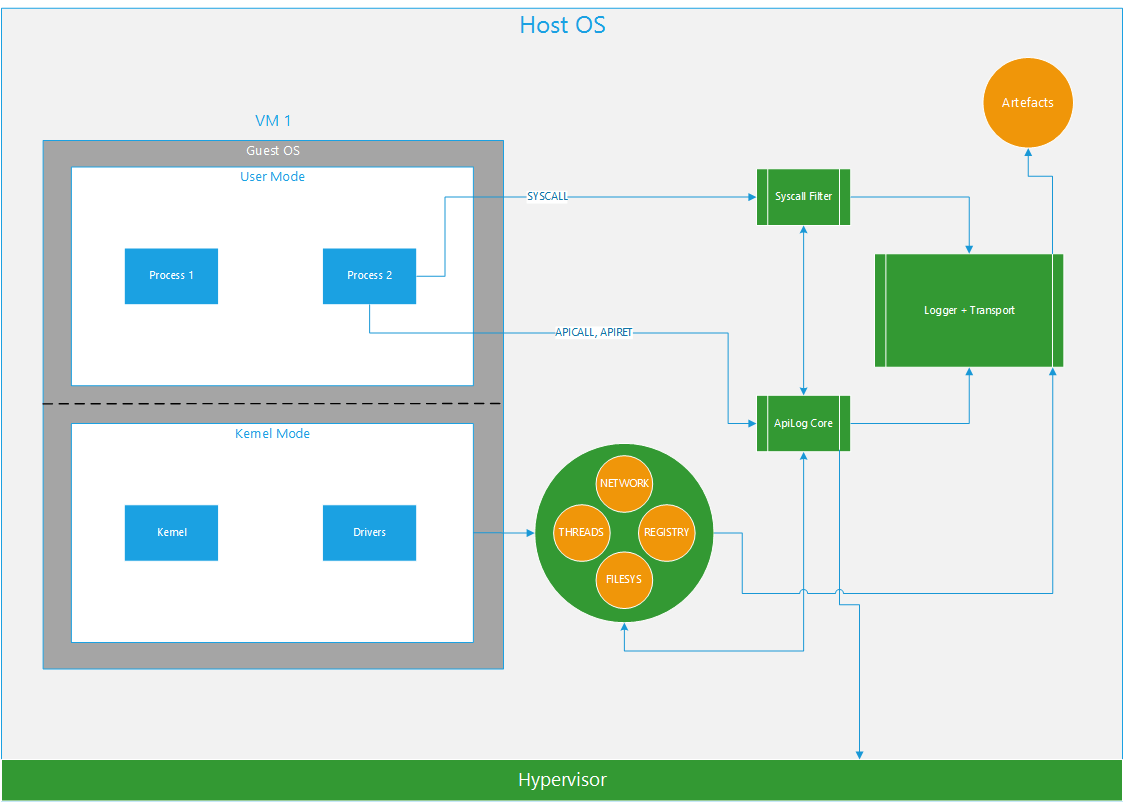

Our sandbox consists of multiple components, each of which is responsible for designated functions. The transport subsystem communicates with the outside world, receives commands from the outside and passes on the collected information. There are subsystems that perform file and network interactions, monitor threads/processes and references to the Windows registry. The logging subsystem collects the input and output information of API functions. There is also a component in the system that emulates user actions. In addition, we have included an option to create and use plugins, so the functional capabilities can be extended.

The advantage of our solution is its broad functionality, plus the logging system can be installed on any operating system or on actual hardware. The image of the guest operating system can be customized to suit the client’s needs.

Our analysts can also create dedicated subprograms to perform detection based on collected artifacts, as well as carry out different types of research. These subprograms include those that operate within the sandbox in real time.

Object processing and artifacts

Depending on the type of file that comes in for processing, it will be ‘packed’ by the Task Processor component into a special kind of packet that contains additional information on how the file should be launched, which operating system to select, the amount of time for processing, etc.

After that, another component, the Task Executor, performs the following actions:

- Launches virtual machine;

- Submits file;

- Applies extra configuration to guest operating system;

- Executes file;

- Waits until execution is complete;

- Scans and/or transfers collected artifacts.

The following artifacts are collected by Kaspersky Lab’s sandbox:

- Program’s execution log (all API function calls with all parameters, plus some events);

- Dumps of various memory ranges, loaded modules etc.;

- All types of changes in file system and system registry;

- PCAP files containing networking data;

- Screenshots.

The logging subsystem

The central mechanism of Kaspersky Lab’s sandbox is the logging subsystem that implements the method of non-invasive interception of called API functions and the return values. This means the subsystem is capable of ‘suspending’ the thread of the process being investigated at those moments when it calls an API function or returns from it, and of processing that event synchronously. All this takes place without any modifications to the code.

For each page of the virtual address space, we introduce an attribute of that page’s association with the DLL Known Module (KM). At any given point in time for a particular thread, either the pages that have the KM attribute installed are executable, or those pages where it has not been installed, but never both at the same time. This means that when an API function call is attempted, control is delegated to the KM page which at that moment is not executable according to the above rule. The processor generates an exception, which results in an exit to the hypervisor, and that event is processed. The exact opposite takes place when the API function returns control.

The left-hand side of the above diagram represents the memory of a typical process: the areas highlighted in red are those where execution of instructions is disabled, and the areas in green are those where execution of instructions is enabled. The right of the diagram shows the same process in two states: execution is enabled in the system libraries or elsewhere, but never both at the same time. Accordingly, if you learn how to turn the entire address space of user mode red at the right time, you can catch the returns from system calls.

For all of this to work, copies of original address space page tables are introduced. They are used to translate the virtual address into a physical address. In one of the copies, the pages with the KM attribute are executable, and the pages without the KM attribute are non-executable. In the other copy, it is the other way around. Each record in this sort of table corresponds to a certain page of the virtual address space and, among other things, has the NX attribute that tells the processor if it can execute the instructions on that page. The above rule defines the content of this attribute, depending on the copy and the page’s association with KM. To keep the copies of page tables up to date, there is a module in the subsystem that reacts synchronously to changes in the original address space and, in accordance with our rules, makes those changes to the copies of the address spaces. The operating system, meanwhile, is unaware of the fact that it is running on copies of the original address space, and as far as it is concerned everything is transparent.

Anti-evasion

Modern malware uses a whole variety of methods to evade execution of code that may expose malicious activity.

The following techniques are used most frequently:

- Detecting a virtual runtime environment (a sandbox, emulator, etc.) from indirect evidence;

- ‘Targeted’ execution: malicious activity is exposed only if the program is launched in the right/required runtime environment, at a specific time, etc.

If malicious code detects a research environment, the following (or more) may happen:

- Instantaneous termination;

- Self-destruction;

- Execution of a useless section of code;

- Execution of a secure section of code;

- Attempt to compromise the detected research system;

- Other.

If the system does not meet the required parameters, the malicious program may perform any of the above, but most probably it will destroy itself so that it leaves no traces in the system.

Sandbox developers need to pay particular attention to evasion techniques, and Kaspersky Lab is no exception. We find out about these techniques from a variety of sources, such as public presentations, articles, open-source tools (e.g. Pafish) and, of course, from analyzing malicious code. Along with the continuous improvements we make to our sandbox, we have also implemented automated randomization of various guest environment parameters to reduce execution evasion rates.

Vault 7 evasion methods

As a result of the Vault 7 leak, we discovered the following information about a potential method for evading code execution in our sandbox:

“The Trojan Upclicker (as reported by eEye) uses the SetWindowsHookExA API with the WH_MOUSE_LL parameter to wait until the user lets up the left mouse button (WM_LBUTTONUP) before performing any malicious functionality (then it injects into Explorer.exe). A sandbox environment that does not mimic mouse actions (probably most of them) will never execute the malicious behavior. This is probably effective against Kaspersky and others.”

This was an interesting assumption, so we immediately checked it. We implemented a console-based application (the source code is attached, so readers can use it to check their sandboxes), and it was little surprise that the function ExecuteEvil() executed successfully.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 |

/* Copyright 2017 AO Kaspersky Lab. All Rights Reserved. Anti-Sandboxing: Wait for Mouse Click PoC: https://wikileaks.org/ciav7p1/cms/page_2621847.html RU: https://securelist.ru/a-modern-hypervisor-as-a-basis-for-a-sandbox/80739/ EN: https://securelist.com/a-modern-hypervisor-as-a-basis-for-a-sandbox/81902/ */ #include "stdafx.h" #include <windows.h> #include <iostream> #include <thread> #include <atomic> HHOOK global_hook = nullptr; std::atomic<bool> global_ready(true); void ExecuteEvil() { std::cout << "This will never be executed in Sandbox" << std::endl; // TODO: add your EVIL code here UnhookWindowsHookEx(global_hook); ExitProcess(42); } LRESULT CALLBACK LowLevelMouseProc(_In_ int nCode, _In_ WPARAM wParam, _In_ LPARAM lParam) { if ( nCode < 0 ) { return CallNextHookEx(nullptr, nCode, wParam, lParam); } if ( nCode == HC_ACTION && wParam == WM_LBUTTONUP && global_ready == true ) { global_ready = false; std::thread(ExecuteEvil).detach(); // execute EVIL thread detached } return CallNextHookEx(nullptr, nCode, wParam, lParam); } int _tmain(int argc, _TCHAR* argv[]) { FreeConsole(); // hide console window global_hook = SetWindowsHookEx(WH_MOUSE_LL, LowLevelMouseProc, nullptr, 0); // emulate message queue MSG msg; while ( GetMessage(&msg, NULL, 0, 0) ) { Sleep(0); } return 0; } |

It came as no surprise, because there is a dedicated component in our sandbox that emulates user actions and whose actions are indistinguishable from those of a regular user. This component exhibits generic behavior and, moreover, it ‘knows’ popular applications, interacting with them just like a regular user, e.g. it ‘reads’ documents opened in Microsoft Word and installs applications if an installer is launched.

Heuristic search for exploits

Thanks to a system of plugins, we can infinitely expand the functionalities of the sandbox. One such plugin, Exploit Checker, detects typical activity of early post-exploitation phases. The events it detects are logged, and the memory assigned to them is dumped to the hard drive for further analysis.

Below are some examples of Exploit Checker events:

- Exploited exceptions:

- DEP violation

- Heap corruption

- Illegal/privileged instruction

- Others

- Stack execution;

- EoP detection;

- Predetection of Heap Spray;

- Execution of user space code in Ring 0;

- Change of process token;

- Others

CVE-2015-2546

Let’s take a look at the vulnerability CVE-2015-2545 and its extension CVE-2015-2546. Microsoft Office versions 2007 SP3, 2010 SP2, 2013 SP1 and 2013 RT SP1 are exposed to the former – it allows remote attackers to execute arbitrary code using a crafted EPS file. The latter allows remote attackers to execute arbitrary code in kernel mode. Both vulnerabilities were used in a targeted attack by the Platinum (aka TwoForOne) group. The attackers first exploited CVE-2015-2545 to execute code in the process WINWORD.EXE, and then CVE-2015-2546 to escalate privileges up to the SYSTEM level.

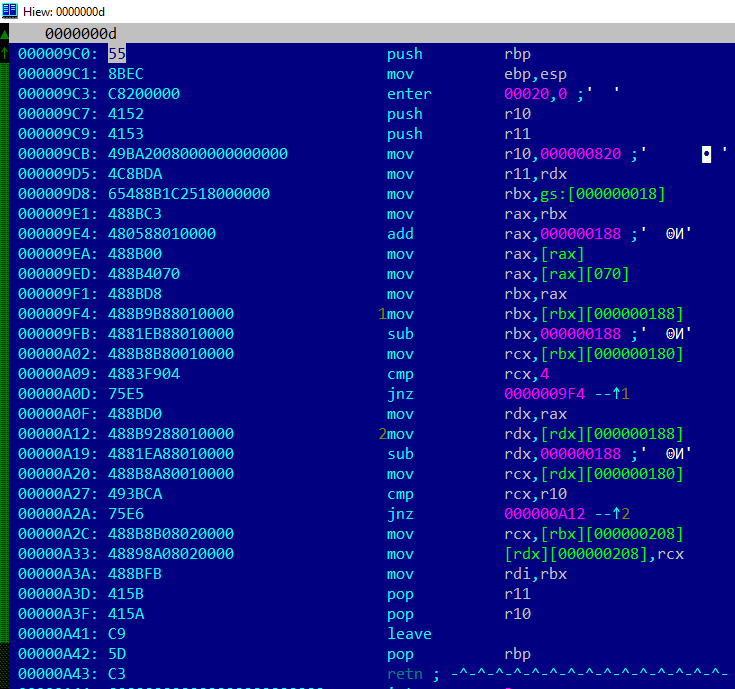

CVE-2015-2546 is a classic Use-After-Free (UAF)-type vulnerability. Exploitation results in an escalation of process privileges up to SYSTEM level. Let’s take a closer look at this second vulnerability.

By detonating a crafted document in our sandbox, we obtained an aggregate execution log which we then filtered for events with the Exploit Checker plugin. This produced quite a lot of events, so we will only present the most interesting, i.e. those that allow us to obtain the shellcode of CVE-2015-2546 – user space code executed in kernel mode. (SMEP is used to counteract this technique.)

|

1 2 3 4 |

[...] <EXPLOIT_CHECK Process="FLTLDR.EXE" Pid="0x000000000000XXXX" Tid="0x000000000000XXXX">UserSpaceSupervisorCPL("VA:0000000001FC29C0",allocbase=0000000001FC0000,base=0000000001FC2000,size=4096(0x1000),dumpBase=0000000001FC2000,dumpid=0xD)</EXPLOIT_CHECK> <EXPLOIT_CHECK Process="FLTLDR.EXE" Pid="0x000000000000XXXX" Tid="0x000000000000XXXX">SecurityTokenChanged()</EXPLOIT_CHECK> [...] |

- We find the dump with ID = 0xD among the memory dumps of the process FLTLDR.EXE;

- The base address of the memory area is 0x1FC2000, the address of the code is located at 0x1FC29C0;

- Shellcode offset equals 0x1FC29C0 — 0x1FC2000 = 0x9C0.

Naturally, the shellcode search algorithm will change depending on the type of vulnerability, but that doesn’t change the basic principle.

Exploit Checker is a plugin for the logging system that provides extra events, based on certain heuristics, to the execution log. Apart from that, it collects the required artifacts: memory dumps that are used for further analysis and for detection.

BlackEnergy in the sandbox

We have already reported on an attack launched in Ukraine by the APT group BlackEnergy using Microsoft Word documents. Here’s a summary of the analysis:

- Microsoft Word documents containing macros were used in the attack;

- A macro drops the file vba_macro.exe, a typical BlackEnergy dropper, to the disk;

- exe drops the file FONTCACHE.DAT, a regular DLL file, to the disk;

- For the DLL file to execute at each system launch, the dropper creates an LNK file in the startup system folder;

- The Trojan connects to its C&C at 5.149.254.114.

Below is a fragment of the execution log that we obtained by detonating a malicious Microsoft Word document in our sandbox running a guest Windows 7 x64 environment.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 |

[0XXX] >> ShellExecuteExW ("[HIDDEN_DIR]\e15b36c2e394d599a8ab352159089dd2.doc") [...] <PROCESS_CREATE_SUCCESS Pid="0xXXX" ParentPid="0xXXX" CreatedPid="0xYYY" /> <PROC_LOG_START Pid="0xYYY" RequestorPid="0xXXX" Reason="OnCreateChild"> <ImagePath>\Device\HarddiskVolumeZ\Program Files (x86)\Microsoft Office\Office14\WINWORD.EXE</ImagePath> <CmdLine>"%PROGRAM_FILES%\Microsoft Office\Office14\WINWORD.EXE" /n "[HIDDEN_DIR]\e15b36c2e394d599a8ab352159089dd2.doc"</CmdLine> </PROC_LOG_START> [...] <LOAD_IMAGE Pid="0xYYY" ImageBase="0x30000000" ImageSize="0x15d000"> <ImagePath>\Device\HarddiskVolumeZ\Program Files (x86)\Microsoft Office\Office14\WINWORD.EXE</ImagePath> </LOAD_IMAGE> <LOAD_IMAGE Pid="0xYYY" ImageBase="0x78e50000" ImageSize="0x1a9000"> <ImagePath>\SystemRoot\System32\ntdll.dll</ImagePath> </LOAD_IMAGE> <LOAD_IMAGE Pid="0xYYY" ImageBase="0x7de70000" ImageSize="0x180000"> <ImagePath>\SystemRoot\SysWOW64\ntdll.dll</ImagePath> </LOAD_IMAGE> [...] [0YYY] >> SetWindowTextW (0000000000050018,00000000001875BC -> "e15b36c2e394d599a8ab352159089dd2.doc [Compatibility Mode] — Microsoft Word") => 00000000390A056C {0000} [...] <FILE_CREATED Pid="0xYYY"> <Name>\Device\HarddiskVolumeZ\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\Temp\vba_macro.exe</Name> </FILE_CREATED> <FILE_WRITE Pid="0xYYY" Position="0x0" Size="0x0000000000000001"> <Name>\Device\HarddiskVolumeZ\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\Temp\vba_macro.exe</Name> </FILE_WRITE> <FILE_WRITE Pid="0xYYY" Position="0x1" Size="0x0000000000000001"> <Name>\Device\HarddiskVolumeZ\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\Temp\vba_macro.exe</Name> </FILE_WRITE> <FILE_WRITE Pid="0xYYY" Position="0x2" Size="0x0000000000000001"> <Name>\Device\HarddiskVolumeZ\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\Temp\vba_macro.exe</Name> </FILE_WRITE> [...] <FILE_WRITE Pid="0xYYY" Position="0x1afff" Size="0x0000000000000001"> <Name>\Device\HarddiskVolumeZ\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\Temp\vba_macro.exe</Name> </FILE_WRITE> <FILE_MODIFIED Pid="0xYYY"> <Name>\Device\HarddiskVolumeZ\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\Temp\vba_macro.exe</Name> </FILE_MODIFIED> [0YYY] << CloseHandle () [00000001] {0000} [...] [0YYY] >> CreateProcessW (0000000000000000 -> (NULL),000000000047FEDC -> "%SYSTEM_ROOT%\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\Temp\vba_macro.exe",0000000000000000,0000000000000000,00000000,00000000,0000000000000000,0000000000000000 -> (NULL),00000000001883B0 -> (STARTUPINFOEXW*){(STARTUPINFOW){,,lpDesktop=0000000000000000 -> (NULL),lpTitle=0000000000000000 -> (NULL),,,,,,,,,wShowWindow=0001,,,,,},},00000000001883F4) => 000000000B87C2F8 {0000} <PROCESS_CREATE_SUCCESS Pid="0xYYY" ParentPid="0xYYY" CreatedPid="0xZZZ" /> <PROC_LOG_START Pid="0xZZZ" RequestorPid="0xYYY" Reason="OnCreateChild"> <ImagePath>\Device\HarddiskVolumeZ\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\Temp\vba_macro.exe</ImagePath> <CmdLine>%SYSTEM_ROOT%\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\Temp\vba_macro.exe</CmdLine> </PROC_LOG_START> <LOAD_IMAGE Pid="0xYYY" ImageBase="0xcb90000" ImageSize="0x1b000"> <ImagePath>\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\Temp\vba_macro.exe</ImagePath> </LOAD_IMAGE> [...] [0ZZZ] << SHGetFolderPathA (,,,,000000000018FCC0 -> "%SYSTEM_ROOT%\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local") [00000000] {0000} [0ZZZ] >> CreateFileA (000000000018FCC0 -> "%SYSTEM_ROOT%\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\FONTCACHE.DAT",40000000,00000000,0000000000000000,00000002,00000002,0000000000000000 -> (NULL)) => 0000000000421160 {0000} <FILE_CREATED Pid="0xZZZ"> <Name>\Device\HarddiskVolumeZ\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\FONTCACHE.DAT</Name> </FILE_CREATED> [...] <FILE_WRITE Pid="0xZZZ" Position="0x0" Size="0x000000000000DE00"> <Name>\Device\HarddiskVolumeZ\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\FONTCACHE.DAT</Name> </FILE_WRITE> [...] <FILE_MODIFIED Pid="0xZZZ"> <Name>\Device\HarddiskVolumeZ\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\FONTCACHE.DAT</Name> </FILE_MODIFIED> [0ZZZ] << CloseHandle () [00000001] {0000} [...] <FILE_CREATED Pid="0xZZZ"> <Name>\Device\HarddiskVolumeZ\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup\{C2F5139C-7918-4CE6-A17C-77B9290128D8}.lnk</Name> </FILE_CREATED> [...] <FILE_WRITE Pid="0xZZZ" Position="0x0" Size="0x000000000000075D"> <Name>\Device\HarddiskVolumeZ\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup\{C2F5139C-7918-4CE6-A17C-77B9290128D8}.lnk</Name> </FILE_WRITE> <FILE_MODIFIED Pid="0xZZZ"> <Name>\Device\HarddiskVolumeZ\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup\{C2F5139C-7918-4CE6-A17C-77B9290128D8}.lnk</Name> </FILE_MODIFIED> [...] [0ZZZ] >> ShellExecuteW (0000000000000000,000000000018FEC8 -> "open",000000000018F8B0 -> "%SYSTEM_ROOT%\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup\{C2F5139C-7918-4CE6-A17C-77B9290128D8}.lnk",0000000000000000 -> (NULL),0000000000000000 -> (NULL),00000000) => 000000000042195D {0000} [...] <PROCESS_CREATE_SUCCESS Pid="0xZZZ" ParentPid="0xZZZ" CreatedPid="0xAAA" /> <PROC_LOG_START Pid="0xAAA" RequestorPid="0xZZZ" Reason="OnCreateChild"> <ImagePath>\Device\HarddiskVolumeZ\Windows\SysWOW64\rundll32.exe</ImagePath> <CmdLine>"%SYSTEM_ROOT%\Windows\System32\rundll32.exe" "%SYSTEM_ROOT%\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\FONTCACHE.DAT",#1</CmdLine> </PROC_LOG_START> [...] [0ZZZ] >> CreateProcessA (000000000018F334 -> "%SYSTEM_ROOT%\Windows\system32\cmd.exe",000000000018EE20 -> "/s /c \"for /L %i in (1,1,100) do (attrib +h \"%SYSTEM_ROOT%\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\Temp\VBA_MA~1.EXE\" & del /A:h /F \"%SYSTEM_ROOT%\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\Temp\VBA_MA~1.EXE\" & ping localhost -n 2 & if not exist \"%SYSTEM_ROOT%\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\FONTCACHE.DAT\" Exit 1)\"",0000000000000000,0000000000000000,00000000,08000000,0000000000000000,0000000000000000 -> (NULL),000000000018F848 -> (STARTUPINFOA*){cb=00000044,lpReserved=0000000000000000 -> (NULL),lpDesktop=0000000000000000 -> (NULL),lpTitle=0000000000000000 -> (NULL),dwX=00000000,dwY=00000000,dwXSize=00000000,dwYSize=00000000,dwXCountChars=00000000,dwYCountChars=00000000,dwFillAttribute=00000000,dwFlags=00000001,wShowWindow=0000,cbReserved2=0000,lpReserved2=0000000000000000,hStdInput=0000000000000000 -> (NULL),,},000000000018F88C) => 0000000000421666 {0000} <PROCESS_CREATE_SUCCESS Pid="0xZZZ" ParentPid="0xZZZ" CreatedPid="0xBBB" /> <PROC_LOG_START Pid="0xBBB" RequestorPid="0xZZZ" Reason="OnCreateChild"> <ImagePath>\Device\HarddiskVolumeZ\Windows\SysWOW64\cmd.exe</ImagePath> <CmdLine>/s /c "for /L %i in (1,1,100) do (attrib +h "%SYSTEM_ROOT%\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\Temp\VBA_MA~1.EXE" & del /A:h /F "%SYSTEM_ROOT%\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\Temp\VBA_MA~1.EXE" & ping localhost -n 2 & if not exist "%SYSTEM_ROOT%\Users\[HIDDEN_USER]\AppData\Local\FONTCACHE.DAT" Exit 1)"</CmdLine> </PROC_LOG_START> [...] |

As a result of executing the malicious document, we obtained the following:

- A log of called API functions in all processes associated with malicious activities;

- Memory maps for all these processes, including both the loaded modules and heap memory;

- All changes to the file system;

- Network packets;

- Screenshots.

This information is more than sufficient for a detailed analysis.

Conclusions

Kaspersky Lab’s sandbox for Windows applications is a large and a complex project that has been running for several years now. During this period, the logging system has demonstrated its effectiveness, so we use it not only in our internal infrastructure but in Kaspersky Anti Targeted Attack Platform too.

The use of a hypervisor has solved numerous problems related to malicious programs detecting sandbox environments. However, cybercriminals are continuously inventing new techniques, so we keep a close watch on the threat landscape and quickly introduce any necessary updates to the code base.

A Modern Hypervisor as a Basis for a Sandbox

Oleg

Impressive capabilities of sandbox and logging environment. Have you considered providing it as a service? Say to aid av community in research and analysis of samples or perhaps exposing APIs to generate Indicators of Compromise that can be used to plug in into Intrusion Detection Systems and|or the third party open source Security Information and Event Management solutions?

xxx

Only 75 HW servers it’s bit unbelivable. I expected at lease 1000 HW servers. Maybe it’s time to switch to cloud ?