Q1 2019 in brief

The Kaspersky Industrial Cybersecurity Conference 2019 takes place this week in Sochi, the seventh such conference dedicated to the problems of industrial cybersecurity. Among other things, the conference will address the security of automation systems in buildings — industrial versions of the now common smart home. Typically, such a system consists of various sensors and controllers to manage elevators, ventilation, heating, lighting, electricity, water supply, video surveillance, alarm systems, fire extinguishing systems, etc.; it also includes servers that manage the controllers, as well as computers of engineers and dispatchers. Such automation systems are used not only in office and residential buildings, but in hospitals, shopping malls, prisons, industrial production, public transport, and other places where large work and/or living areas need to be controlled.

We decided to study the live threats to building-based automation systems and to see what malware their owners encountered in the first six months of 2019.

Malware and target systems

According to KSN, in H1 2019 Kaspersky products blocked malicious objects on 37.8% of computers in building-based automation systems (from a random sample of more than 40,000 sources).

Share of smart building systems on which malware was blocked, 2018-2019

It should be mentioned right away that most of the blocked threats are neither targeted, nor specific to building-based automation systems. In other words, it is ordinary malware regularly found on corporate networks unrelated to automation systems. This does not mean, however, that such malware can be ignored — it has numerous side effects that can have a significant impact on the availability and integrity of automation systems, from file encryption (including databases) to denial of service on network equipment and workstations as a result of malicious traffic and unstable exploits. Spyware and backdoors (botnet agents) pose a far greater threat, since stolen authentication data and the remote control it provides can be used to plan and carry out a targeted attack on a building’s automation system.

What are the threats of a targeted attack? First off, there is disruption of the computers that control the automation systems, and subsequent failure of the systems themselves, since not all of them are totally autonomous. The result may be a disruption of the normal operation of the building: electricity, water, and ventilation are likely to continue to work as before, but there may be problems with opening/closing doors or using elevators. There may also be problems with the fire extinguishing system, for example, a false alarm or, worse, no signal in the event of a fire.

Geographical distribution of threats

Top 10 countries

| Country | %* |

| Italy | 48.5 |

| Spain | 47.6 |

| Britain | 44.4 |

| Czech Republic | 42.1 |

| Romania | 41.7 |

| Belgium | 38.5 |

| Switzerland | 36.8 |

| India | 36.8 |

| China | 36.0 |

| Brazil | 33.3 |

*Share of computers on which malware was blocked

Sources of threats to building-based automation systems

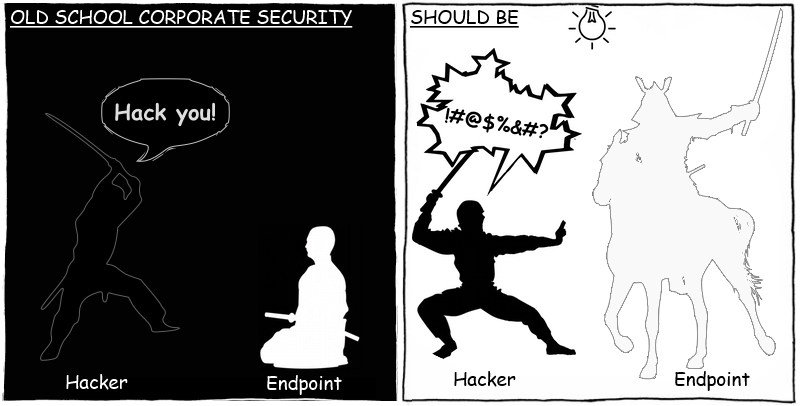

When studying the sources of threats to building-based automation systems, we decided to compare them with similar statistics on industrial systems that we regularly compile and publish. Here’s the result:

Sources of threats to building-based automation systems by share of attacked computers, H1 2019

The graph shows that in building-based automation systems the share of attacked computers is consistently higher than in industrial systems. That being the case, the total share of attacked computers over the same period is greater in industrial systems (41.2%). This is due to the fact that building-based automation systems are more similar to systems in the IT segment — on the one hand, they are better protected than industrial ones, so the overall percentage is lower; on the other, they have a large attack surface (i.e. the majority have access to the Internet and often use corporate mail and removable drives), so each computer is exposed to more threats from different sources.

Types of malware detected in building-based automation systems, by share of users attacked, H1 2019

Note that it is not only the networks of automation systems in specific buildings (stations, airports, hospitals, etc.) that face threats. The networks of developers, integrators, and operators of such systems, who have (often privileged) remote access to a huge number and variety of objects, are also subjected to “random” and targeted attacks. Having gained access to computers in the network of an integrator or dispatcher, the cybercriminals can, theoretically, attack many remote objects simultaneously. At the same time, the remote connection to the automation object on the side of the integrator/operator is considered trusted and often effectively uncontrolled.

The threat landscape for smart buildings and how to minimize it will be discussed in more detail at the conference. One final note is to mention the importance of monitoring network communications on the perimeter and inside the network of automation systems. Even minimal monitoring will reveal current issues and violations, the elimination of which will significantly increase the object’s level of security.

Threat landscape for smart buildings

Leo Kangwa

In your document, what does the abbreviation ICS stand for please? Thank you, for this type of information.

Securelist

Hi Leo,

ICS stands for industrial control systems. In the diagram in question, threats to smart buildings are compared with threats to industrial control systems.