The statistical data for this report came from all Kaspersky Lab mobile security solutions, not just Kaspersky Mobile Antivirus for Android. Consequently, the comparative data for 2017 may differ from the data for the same period published in the previous report. The analytical scope was expanded due to the growing popularity of various Kaspersky Lab products and their geographical reach, which made it possible to obtain statistically reliable data. On the whole, the more products we use in compiling the statistics, the more accurate the mobile threatscape that emerges.

Figures of the year

In 2018, Kaspersky Lab products and technologies detected:

- 5,321,142 malicious installation packages

- 151,359 new mobile banking Trojans

- 60,176 new mobile ransomware Trojans

Trends of the year

Users of mobile devices in 2018 faced what could be the strongest cybercriminal onslaught ever seen. Over the course of the year, we observed both new mobile device infection techniques (for example, DNS hijacking) and a step-up in the use of tried-and-tested distribution schemes (for example, SMS spam). Virus writers were focused on:

- Droppers (Trojan-Dropper), designed to bypass detection

- Attacks on bank accounts via mobile devices

- Apps that can be used by cybercriminals to cause damage (RiskTool)

- Adware apps

In 2018, we uncovered three mobile APT campaigns aimed primarily at spying on victims, including reading messages in social networks. Alongside these campaigns, this report touches on all the major events in the world of mobile threats that occurred during the year.

Rise of the droppers

In the past three years, dropper Trojans have become the weapon of choice for cybercriminals specializing in mobile malware. The methods for assembling these Matryoshka-like programs were streamlined, allowing them to be easily created, used and sold by various groups. A dropper creator may have several clients involved in developing ransomware Trojans, banking Trojans, and apps showing persistent ads. Droppers are used as a means to hide the original malicious code, which simultaneously:

- Counteracts detection. The dropper works particularly well against detection based on file hashes, since it generates a new hash each time, while the malware inside does not change a single byte.

- Enables any number of unique files to be created. Virus writers need this, for instance, when using their platform with a fake app store.

Although mobile droppers are nothing new, in Q1 2018 we saw a sharp rise in the number of users attacked by packed malware. The biggest contribution was made by members of the Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Piom family. Growth continued in Q2 and beyond, but much more smoothly. There is no doubt that established groups that have not yet embraced droppers will soon either create their own or buy ready-made ones. This trend will affect the statistical map of detected threats: we will see fewer unique mobile malware families, replaced by droppers of various kinds.

Banking Trojans ride the wave

Last year’s stats on the number of attacks involving mobile banking Trojans were eye-catching. At the beginning of 2018, it seemed that this type of threat had stabilized both by number of unique samples discovered and by number of users attacked. However, already by Q2 the situation had radically changed for the worse. New records were set in terms of both number of mobile banking Trojans detected and number of attacked users. The root cause of this hike is not clear, but the main culprits are the creators of the Asacub and Hqwar Trojans. The former has quite a long history — according to our data, the group behind it has been at work for more than three years. Asacub itself evolved from an SMS Trojan that was armed from the get-go with tools to counteract deletion and intercept incoming calls and SMS messages. Later, the creators of the malware beefed up its logic and began mass distribution using the same attack vector as before: social engineering via SMS. Online forums where people often expect messages from unfamiliar users became a source of mobile numbers. Next, the avalanche propagation method kicked in, with infected devices themselves becoming distributors — Asacub sent itself to everyone in the victim’s phone book.

However, banking Trojans in 2018 were noteworthy not just in terms of scale, but mechanics as well. One aspect of this is the increasingly common use of Accessibility Services in banking threats. This is partly a response to new versions of Android that make it increasingly difficult to overlay phishing windows on top of banking apps, and partly the fact that using Accessibility allows the Trojan to lodge itself in the device so that users cannot remove it by themselves. What’s more, cybercriminals can use Accessibility Services to hijack a perfectly legitimate application and force it, say, to launch a banking app to make a money transfer right there on the victim’s device. Techniques have also appeared to counter dynamic analysis; for example, the Rotexy Trojan checks to see if it is running in a sandbox. However, this is not exactly a new thing, since we have observed such behavior before. That said, it should be noted that combined with obfuscation, anti-dynamic analysis techniques can be effective if virus writers manage to infiltrate their Trojan into a popular app store, in which case both static and dynamic processing may be powerless. Although sandbox detection cannot be said to be common practice among cybercriminals, the trend is evident, and we are inclined to believe that such techniques will become very sophisticated in the near future.

Adware and potentially dangerous software

Throughout 2018, these two classes of mobile apps were in the Top 3 by number of installation packages detected. The reasons for this are many, but chief among them is the fact that adware and attacks on advertisers are a relatively safe method of enrichment for cybercriminals. Attacks of this kind do not cause damage to mobile device owners, save for some rare cases of devices overheating and burning up from the activity of an adware app deployed on them with root access. The harm is done to advertisers, since they pay for their banners being clicked by robots — infected mobile devices. Sure, there are adware apps that make it near impossible to use an infected device. For example, the victim might have to click on a dozen banners before being able to send an SMS. The problem is compounded by the fact that at the initial stages the user does not know which app installation (a flashlight or favorite game, say) led to such dire consequences, since ads are shown at random times and outside the interface of the adware-carrying app. And it only takes one such app to be installed and started for another dozen similar ones to appear, turning the device into an adware zombie. In the worst case scenario, this new wave will have a module with an exploit allowing it to write itself to the system directory or the factory settings rollback script. After that, the only way to restore the operational capacity of the device is to search for the original factory version of the firmware and download it via USB.

On a separate note, one click per banner costs less than a peanut, which is the key reason for the endless stream of unique adware apps — the more of them cybercriminals create and distribute, the more money they get. Lastly, adware modules are often coded without taking into account the confidentiality of the data transmitted, which means that requests to the advertiser’s infrastructure can be sent in unencrypted HTTP traffic and contain any amount of information about the victim, up to and including geolocation.

A slightly different situation is seen with RiskTool software, which had the largest share of all mobile threats detected in 2018. In-app purchases have long been a feature worldwide, whereby the device is tied to an account linked to a bank card. All processes are transparent to the user, and purchases can be canceled. RiskTool-type apps also feature an option for users to buy access to new levels in a game or a picture of a pretty girl, for example, but payment is totally non-transparent to the user. The app itself sends an SMS to a special number without any user involvement, and receives a confirmation message, which RiskTool reacts to; hence, the app knows about the successful payment and shows the purchased content. But the release of the promised content remains at the discretion of the app creators.

As a result, there is a huge number of RiskTool programs used to sell any content, but not requiring any significant development effort — in terms of technical implementation, sending a single SMS is doable for any novice programmer.

There is currently no reason to believe that the flood of adware and RiskTool-class apps will abate, and in 2019 we will likely see a similar picture.

Sharp rise in mobile miners

In 2018, we observed a fivefold increase in attacks using mobile miner Trojans. This growth can be attributed to several factors:

- Mobile devices are being fitted with ever more powerful graphics processors, making them a more effective tool for cryptocurrency mining

- Mobile devices are relatively easy to infect

- Mobile devices are ubiquitous

Although miners are not the most conspicuous type of mobile malware, the load they generate is easily detectable by the device owner. And as soon as the latter suspects malicious activity, they will take measures to get rid of the infection. So to compensate for the outflow of victims, cybercriminals are deploying new large-scale campaigns and enhancing their malware anti-removal mechanisms.

Technologically unpretentious, mobile miners are usually based on ready-made cross-platform malware code (for example, one that works well on Linux) — one needs only to insert receiving cryptocurrency wallet address and wrap the payload inside a mobile app with a minimal graphical interface. Distribution is via various kinds of spam and other typical methods.

Although miners cannot claim to have dislodged other mobile malware from the top positions in 2018, this does not negate the seriousness of the threat. If the miner is poorly coded or its author too greedy, the malware can damage the device’s battery or, worse, cause it to overheat and fail.

Statistics

In 2018, we detected 5,321,142 malicious mobile installation packages, which is down 409,774 on last year.

Despite this drop, in 2018 we recorded a doubling of the number of attacks using malicious mobile software: 116.5 million (against 66.4 million in 2017).

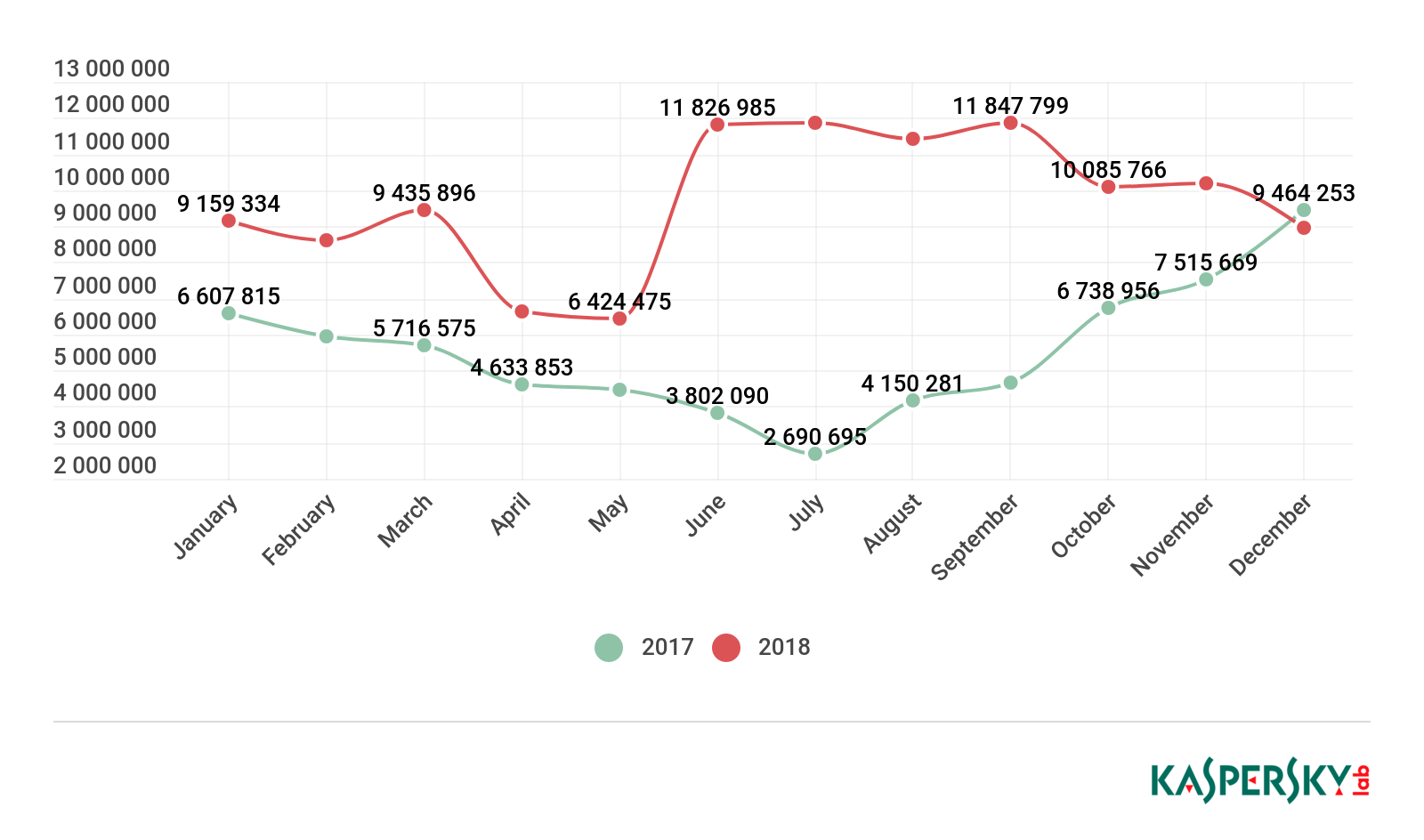

Number of attacks defeated by Kaspersky Lab products, 2018

The number of attacked users also continued its upward trajectory. From the beginning of January to the end of December 2018, Kaspersky Lab protected 9,895,774 unique users of Android devices — up 774,000 against 2017.

Number of attacked users, 2018

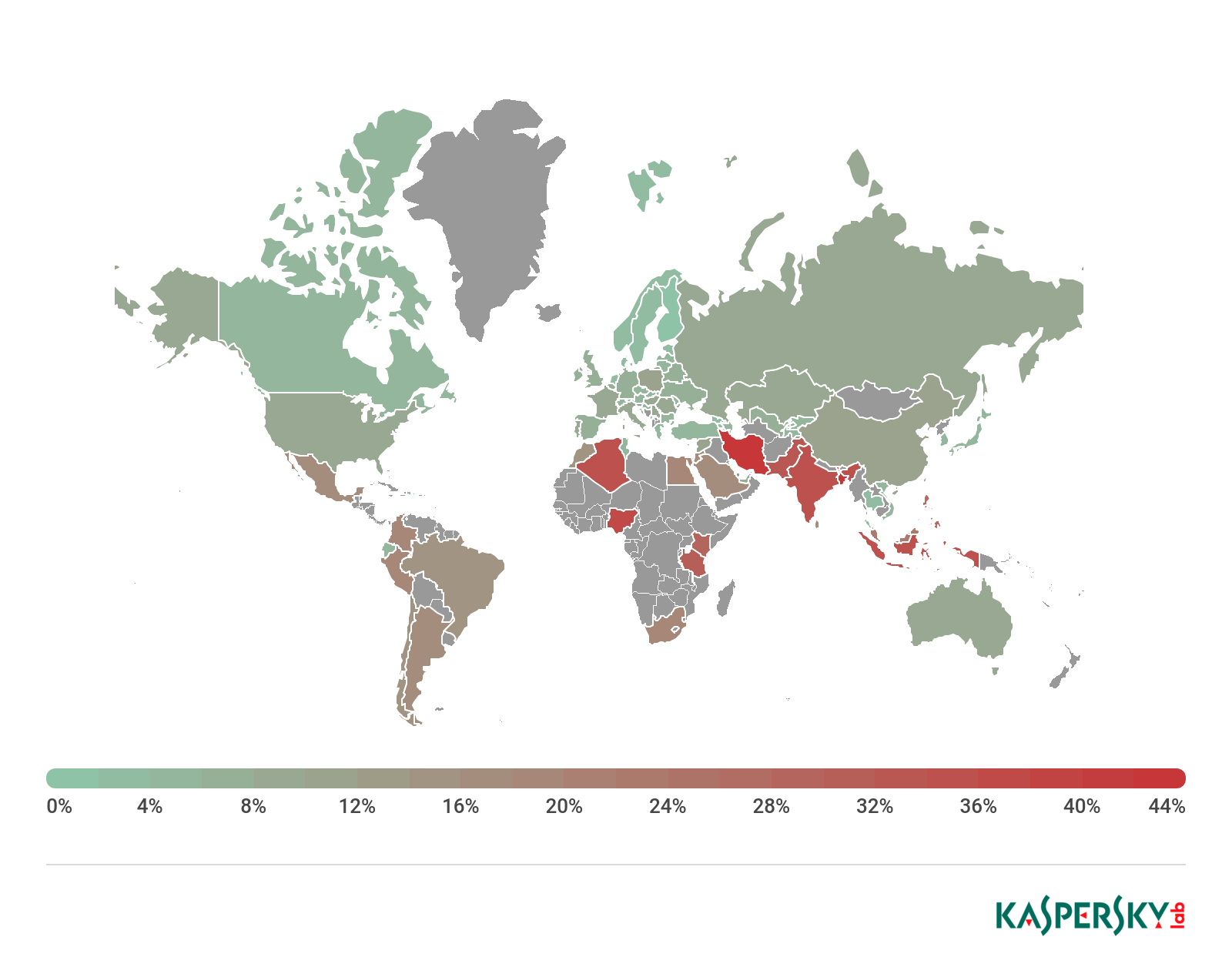

Geography of attacked users, 2018

Top 10 countries by share of users attacked by mobile malware

| Country* | %** |

| Iran | 44.24 |

| Bangladesh | 42.98 |

| Nigeria | 37.72 |

| India | 36.08 |

| Algeria | 35.06 |

| Indonesia | 34.84 |

| Pakistan | 32.62 |

| Tanzania | 31.34 |

| Kenya | 29.72 |

| Philippines | 26.81 |

* Excluded from the rating are countries with fewer than 25,000 active users of Kaspersky Lab mobile solutions over the reporting period.

** Unique users attacked in the country as a percentage of all users of Kaspersky Lab mobile solutions in the country.

Both Iran (44.24%) and Bangladesh (42.98%) retained their leading positions in the Top 10, but in Iran the percentage of infected devices fell significantly by 13 p.p. As in the previous year, the most widespread malware in Iran was the Trojan.AndroidOS.Hiddapp family. In Bangladesh, as in 2017, adware programs from the Ewind family were most common.

Nigeria (37.72%) climbed from fifth place in 2017 to third; the most common adware programs there come from the Ocikq, Agent, and MobiDash families.

Types of mobile malware

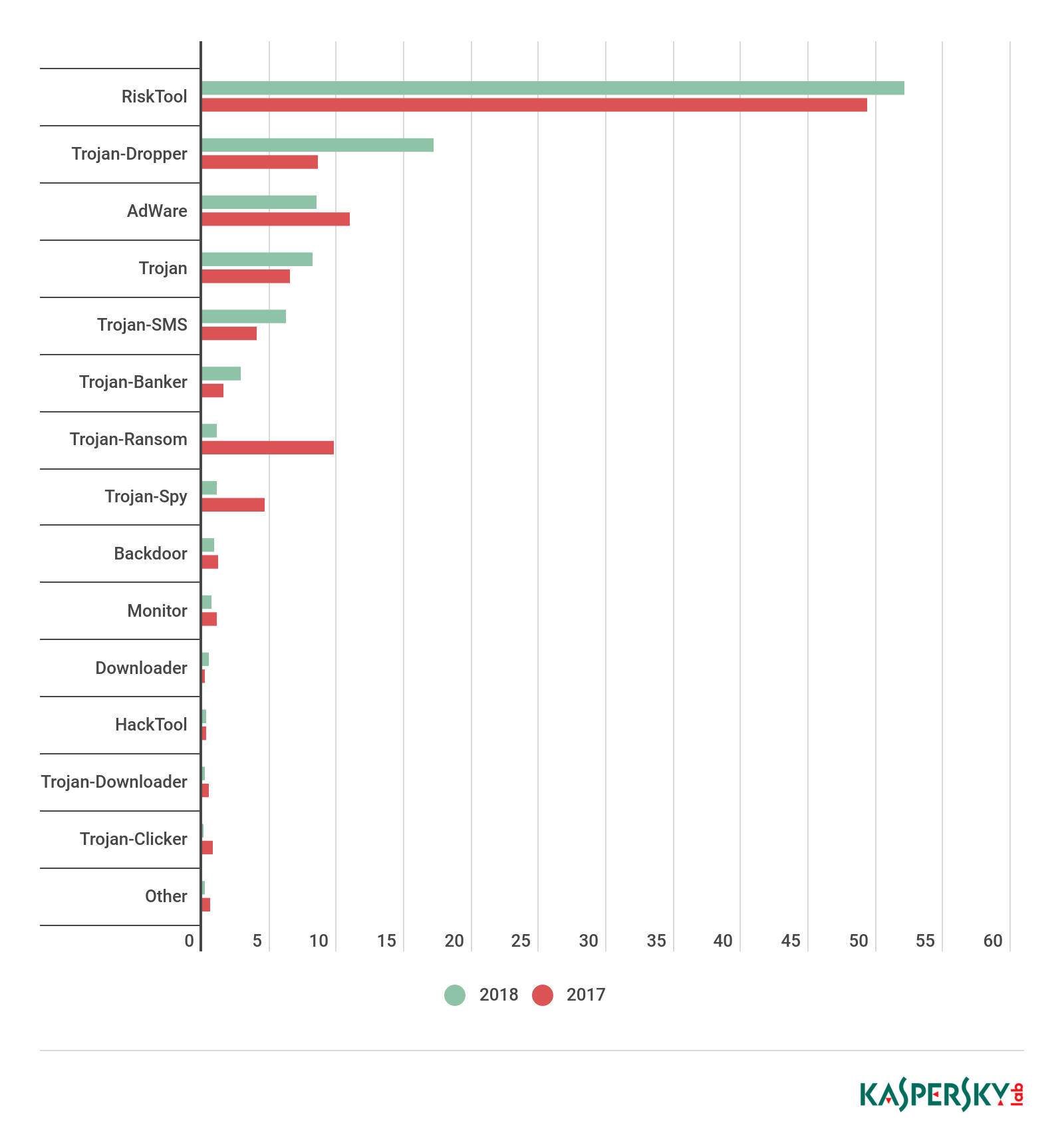

Distribution of new mobile threats by type, 2017 and 2018

Of all detected threats in 2018, the situation with mobile ransomware Trojans (1.12%) was the rosiest, with their share cut drastically by 8.67 p.p. It was a similar story with spyware Trojans (1.07%), whose share fell by 3.55 p.p. Adware apps (8.46%) also lost ground in comparison with 2017.

Trojan-Dropper threats were a marked exception, almost doubling their share from 8.63% to 17.21%. This growth reflects cybercriminals’ appetite to use mobile droppers to wrap all sorts of payloads: banking Trojans, ransomware, adware, etc. This trend looks set to continue in 2019.

Unfortunately, like Trojan-Dropper, the share of financial threats in the shape of mobile bankers also practically doubled — from 1.54% to 2.84%.

Surprisingly, SMS Trojans (6.20%) made the Top 5 by number of objects detected. This dying breed of threats is common only in a handful of countries, but that did not stop its share from increasing against 2017. Although there is no imminent talk of a revival of this class, it is still worth disabling paid subscriptions on your mobile device.

Creators of RiskTool-class threats in 2018 were just as active as last year, and not only reclaimed top position (52.06%), but even showed a slight increase.

Top 20 mobile malware

The malware rating below does not include potentially unwanted software, such as RiskTool and AdWare.

| Verdict | %* | |

| 1 | DangerousObject.Multi.Generic | 68.28 |

| 2 | Trojan.AndroidOS.Boogr.gsh | 10.67 |

| 3 | Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Asacub.a | 6.55 |

| 4 | Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Asacub.snt | 5.19 |

| 5 | Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar.ba | 3.78 |

| 6 | Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Lezok.p | 3.06 |

| 7 | Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Asacub.ce | 2.98 |

| 8 | Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar.gen | 2.96 |

| 9 | Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Asacub.ci | 2.95 |

| 10 | Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Svpeng.q | 2.87 |

| 11 | Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar.bb | 2.77 |

| 12 | Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Asacub.cg | 2.31 |

| 13 | Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.dl | 1.99 |

| 14 | Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar.i | 1.84 |

| 15 | Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Piom.kc | 1.61 |

| 16 | Exploit.AndroidOS.Lotoor.be | 1.39 |

| 17 | Trojan.AndroidOS.Agent.rx | 1.32 |

| 18 | Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Agent.dq | 1.31 |

| 19 | Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Lezok.b | 1.22 |

| 20 | Trojan.AndroidOS.Dvmap.a | 1.14 |

* Share of all users attacked by this type of malware in the total number of users attacked.

Wrapping up 2018, first place in our Top 20 mobile malware, as in previous years, goes to the verdict DangerousObject.Multi.Generic (68.28%) used for malware detected using cloud technologies in cases when the Anti-Virus databases still have no signatures or heuristics to detect it. This way, the most recent malware is uncovered.

In second place was the verdict Trojan.AndroidOS.Boogr.gsh (10.67%). This is assigned to files recognized as malicious by our machine-learning system.

Third, fourth, seventh, and ninth positions were taken by members of the Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Asacub family, one of the main financial threats of 2018.

Fifth and eighth places went to Trojan droppers in the Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar family; they can contain malware of various families related to financial threats and adware.

The Top 10 threats also featured the old-timer Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Svpeng.q (2.87%), which was the most common mobile banking Trojan in 2016. This Trojan uses phishing windows to steal bank card data, and also attacks SMS banking systems.

Of particular note in the ranking are positions 13 and 20, occupied respectively by Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.dl (1.99%) and Trojan.AndroidOS.Dvmap.a (1.44%). These two Trojans are extremely dangerous, since they use superuser privileges to carry out their malicious activity. In particular, they place their components in the device’s system area, which the user only has read access to, and hence they cannot be removed using regular system tools.

Mobile banking Trojans

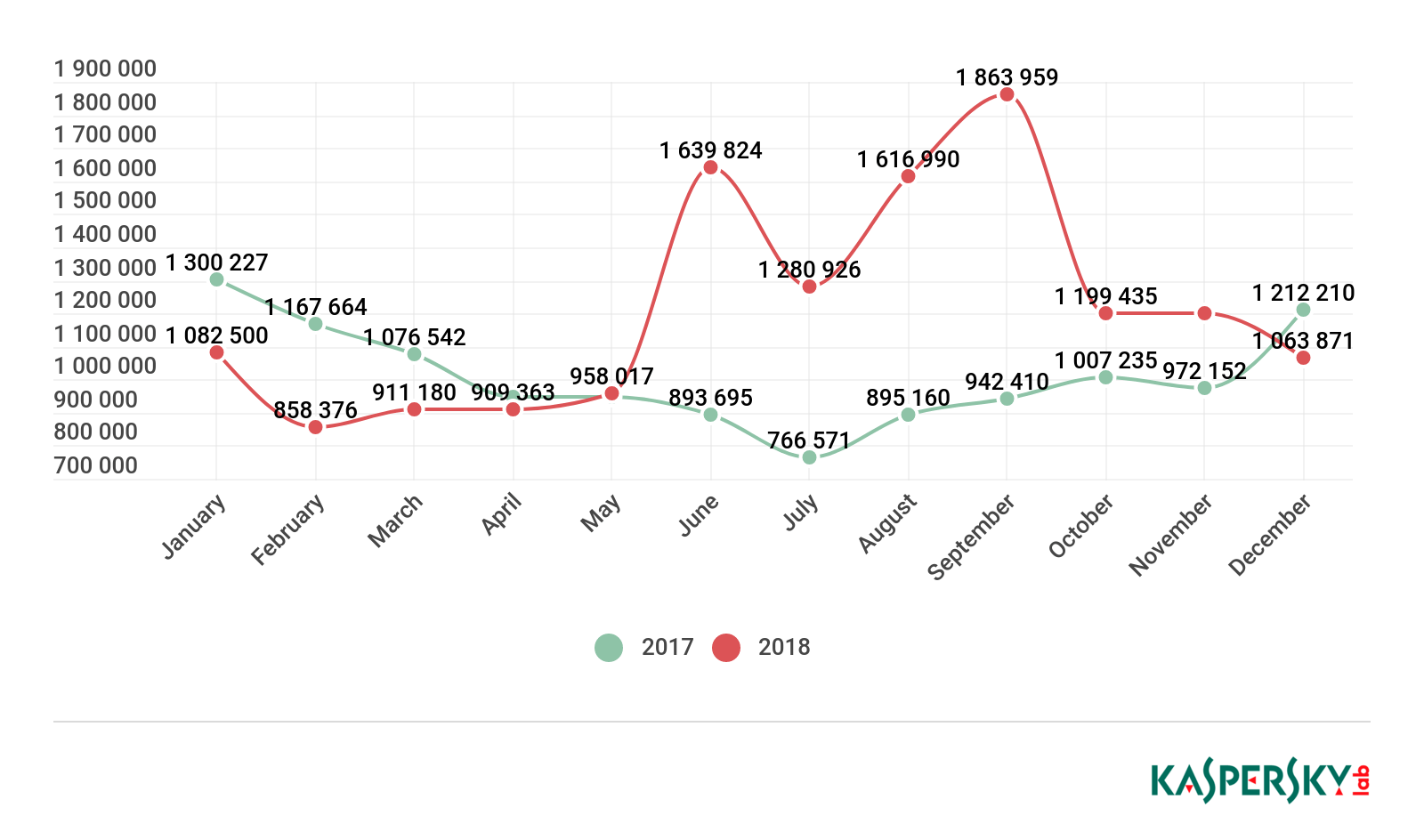

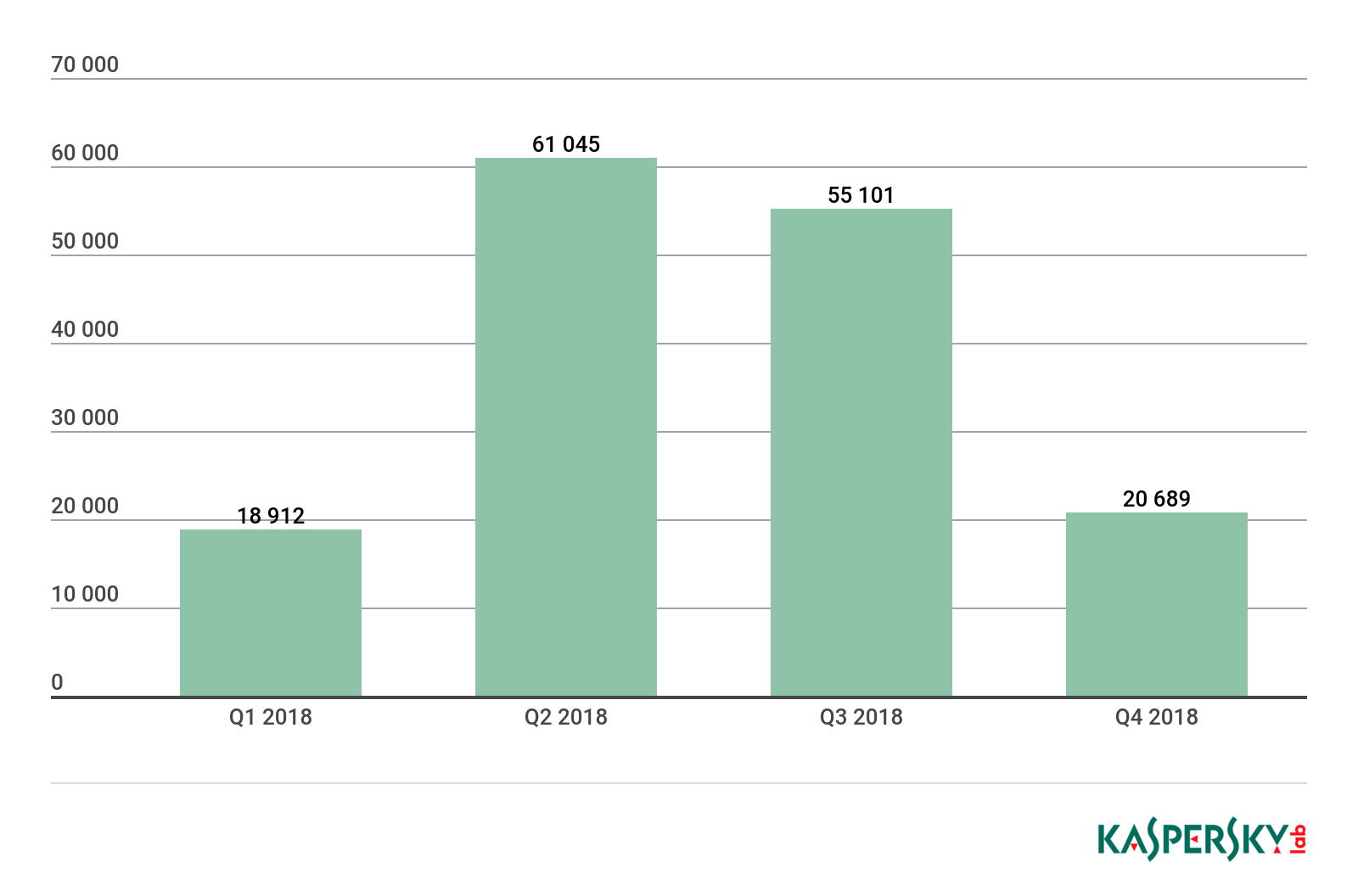

In 2018, we detected 151,359 installation packages for mobile banking Trojans, which is 1.6 times more than in the previous year.

Number of installation packages for mobile banking Trojans detected by Kaspersky Lab, 2018

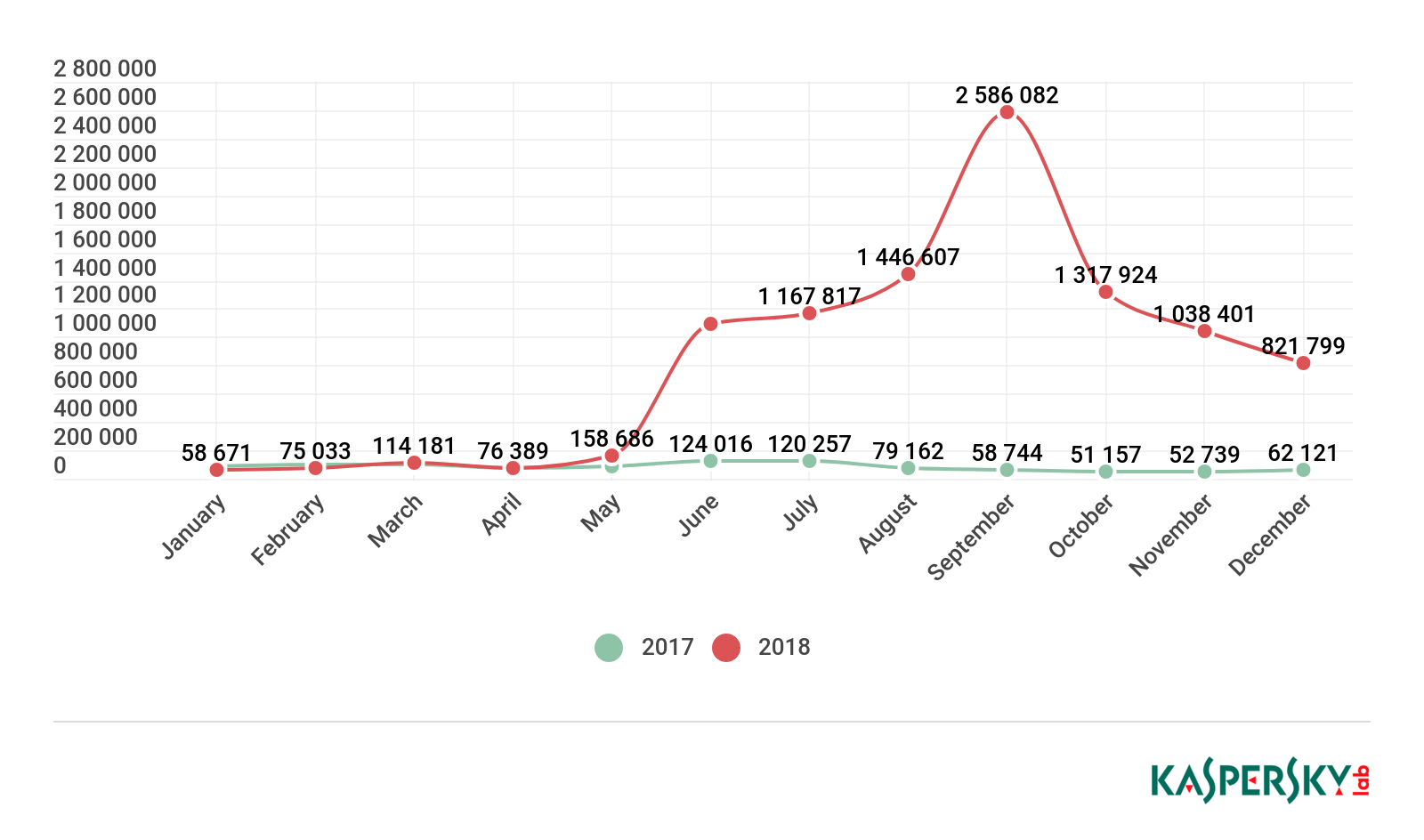

Monitoring the activity of mobile banking Trojans, we registered a giant leap in the number of attacks using this malware. Nothing like this has ever been observed before. The growth began in May 2018, and the attacks peaked in September. The culprits were the Asacub and Hqwar families, due to their members spreading with record frequency.

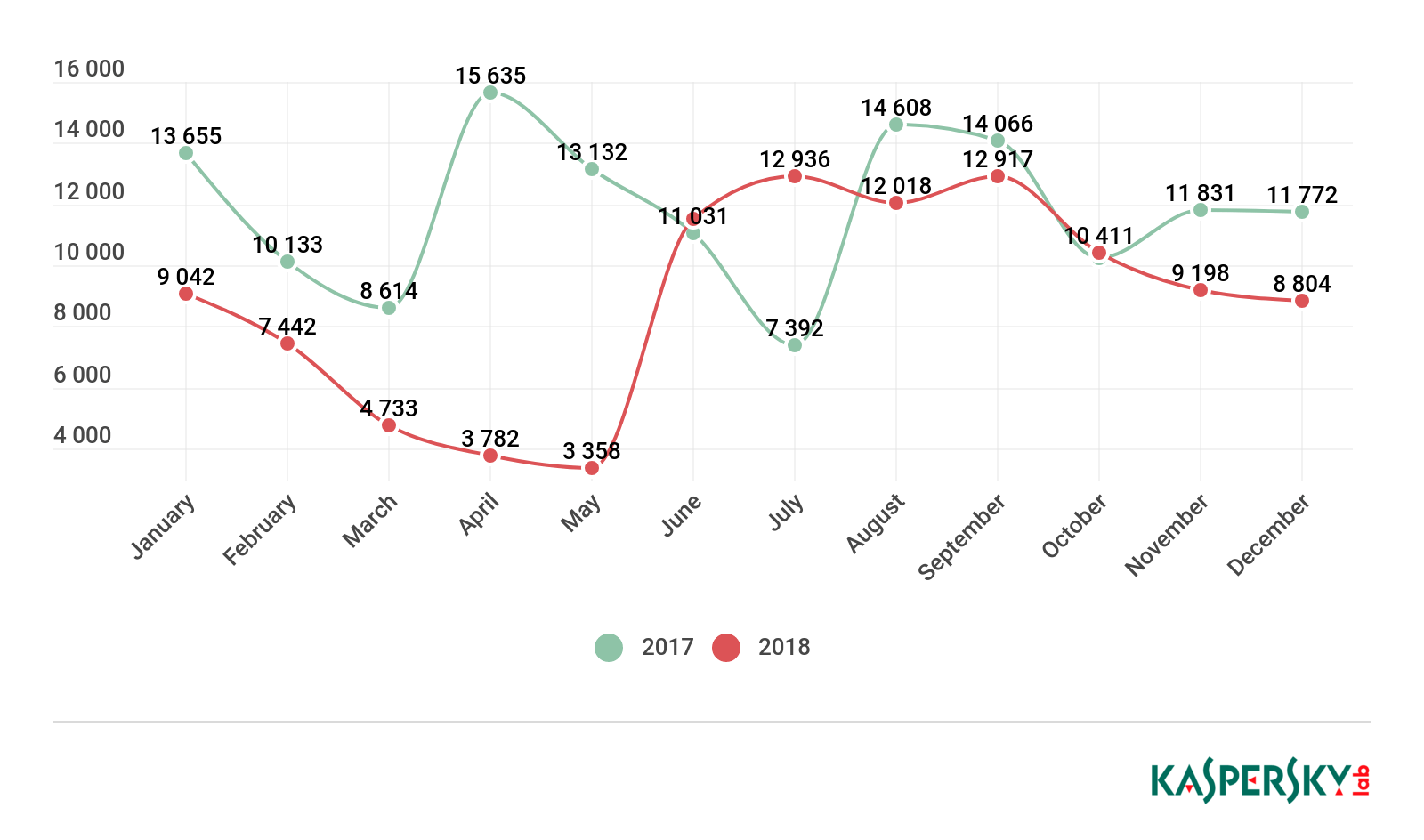

Number of attacks by mobile banking Trojans, 2017 and 2018

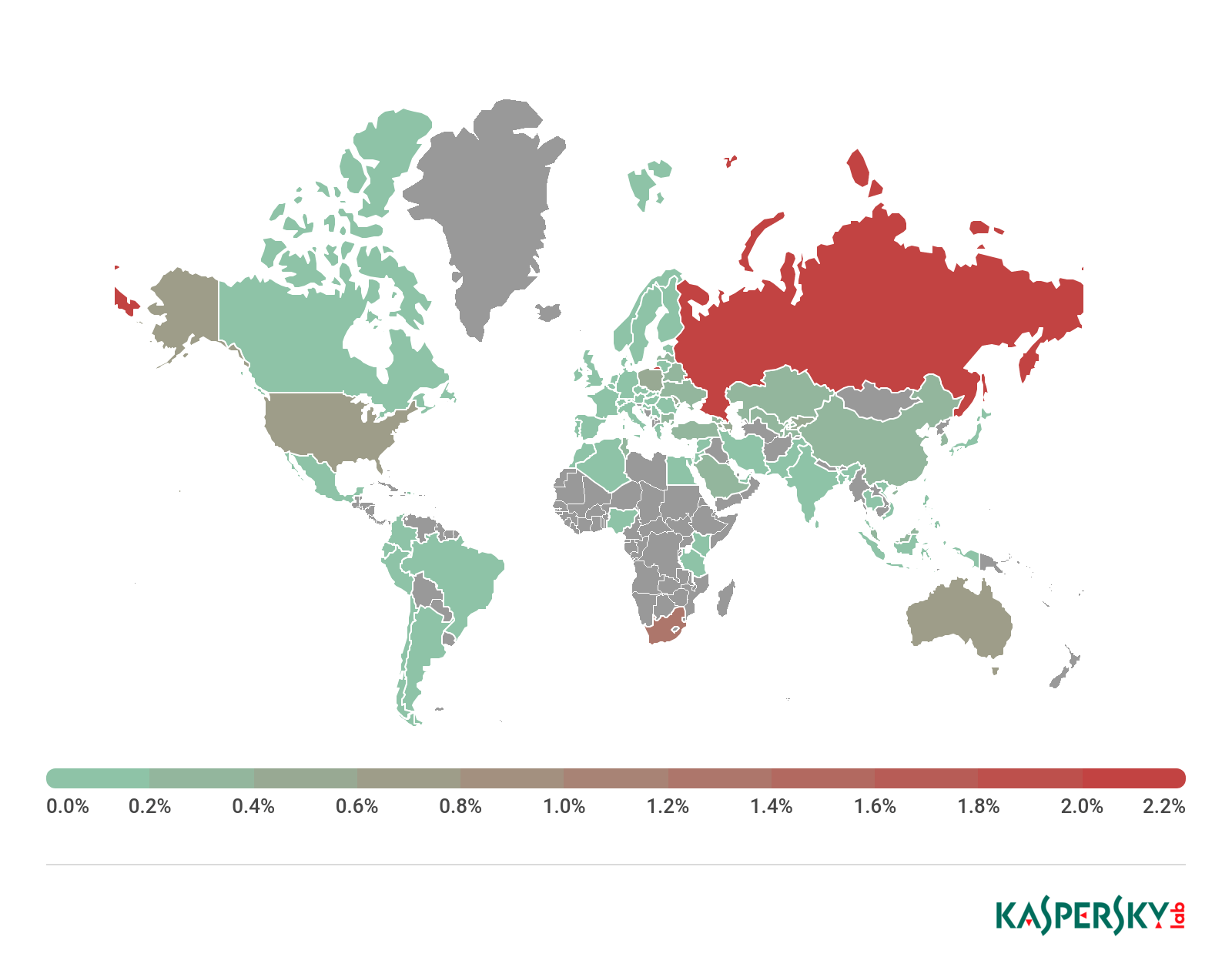

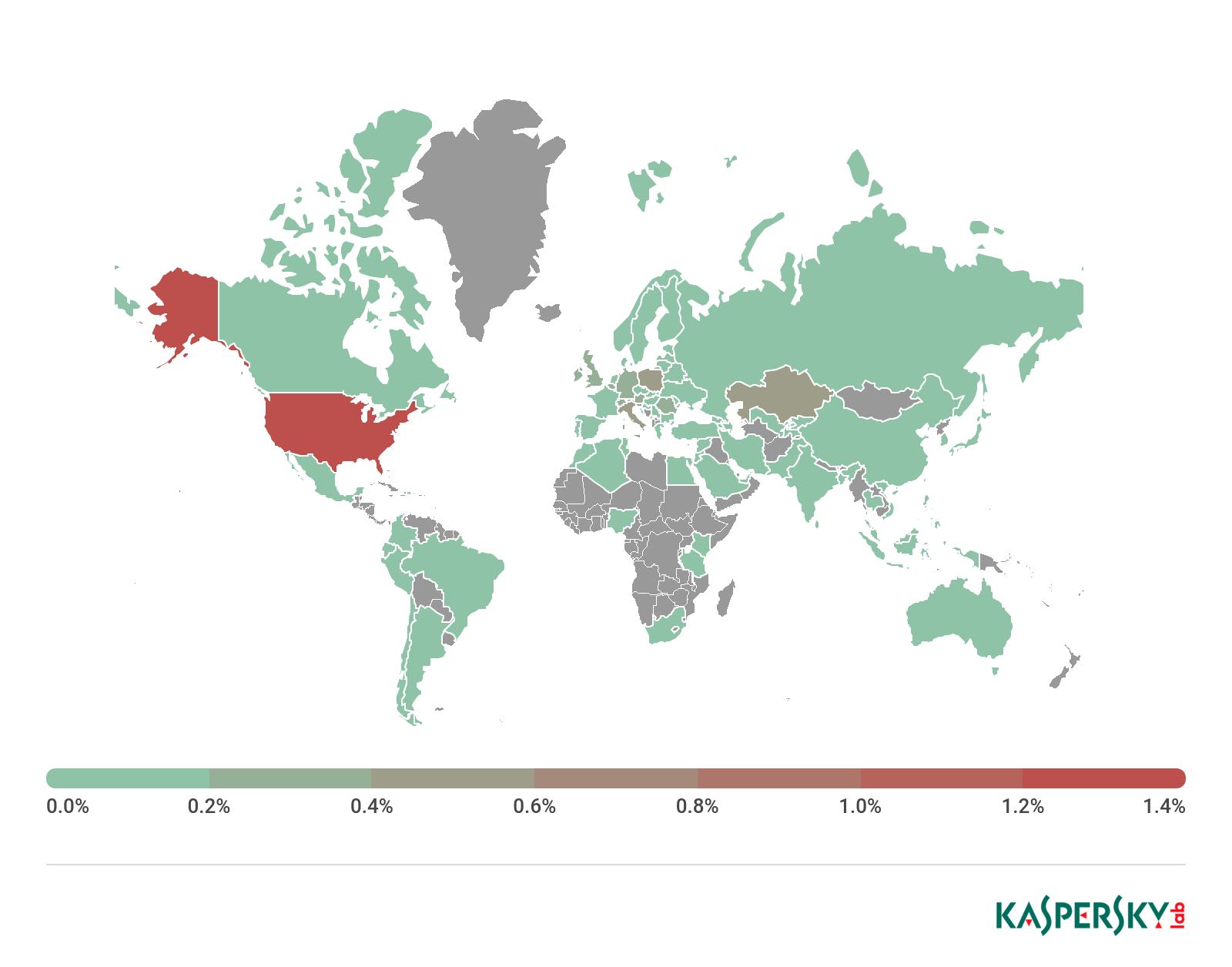

Countries by share of users attacked by mobile bankers, 2018

Top 10 countries by share of all users attacked by mobile bankers

| Country* | %** |

| Russia | 2.32 |

| South Africa | 1.27 |

| US | 0.82 |

| Australia | 0.71 |

| Armenia | 0.51 |

| Poland | 0.46 |

| Moldova | 0.44 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 0.43 |

| Azerbaijan | 0.43 |

| Georgia | 0.42 |

* Excluded from the rating are countries with fewer than 25,000 active users of Kaspersky Lab mobile solutions over the reporting period.

** Unique users attacked by mobile bankers in the country as a percentage of all users of Kaspersky Lab mobile solutions in the country.

In top position, like last year, was Russia, where 2.32% of users encountered mobile banking Trojans. The most common familes in Russia were Asacub, Svpeng, and Agent.

In second-place South Africa (1.27%), where members of the Agent banking family were the most active spreaders. US users (0.82%) most frequently encountered members of the Svpeng and Asacub banking families.

The most common family of mobile bankers in 2018 was Asacub — its members attacked 62.5% of all users who encountered mobile bankers.

Mobile ransomware Trojans

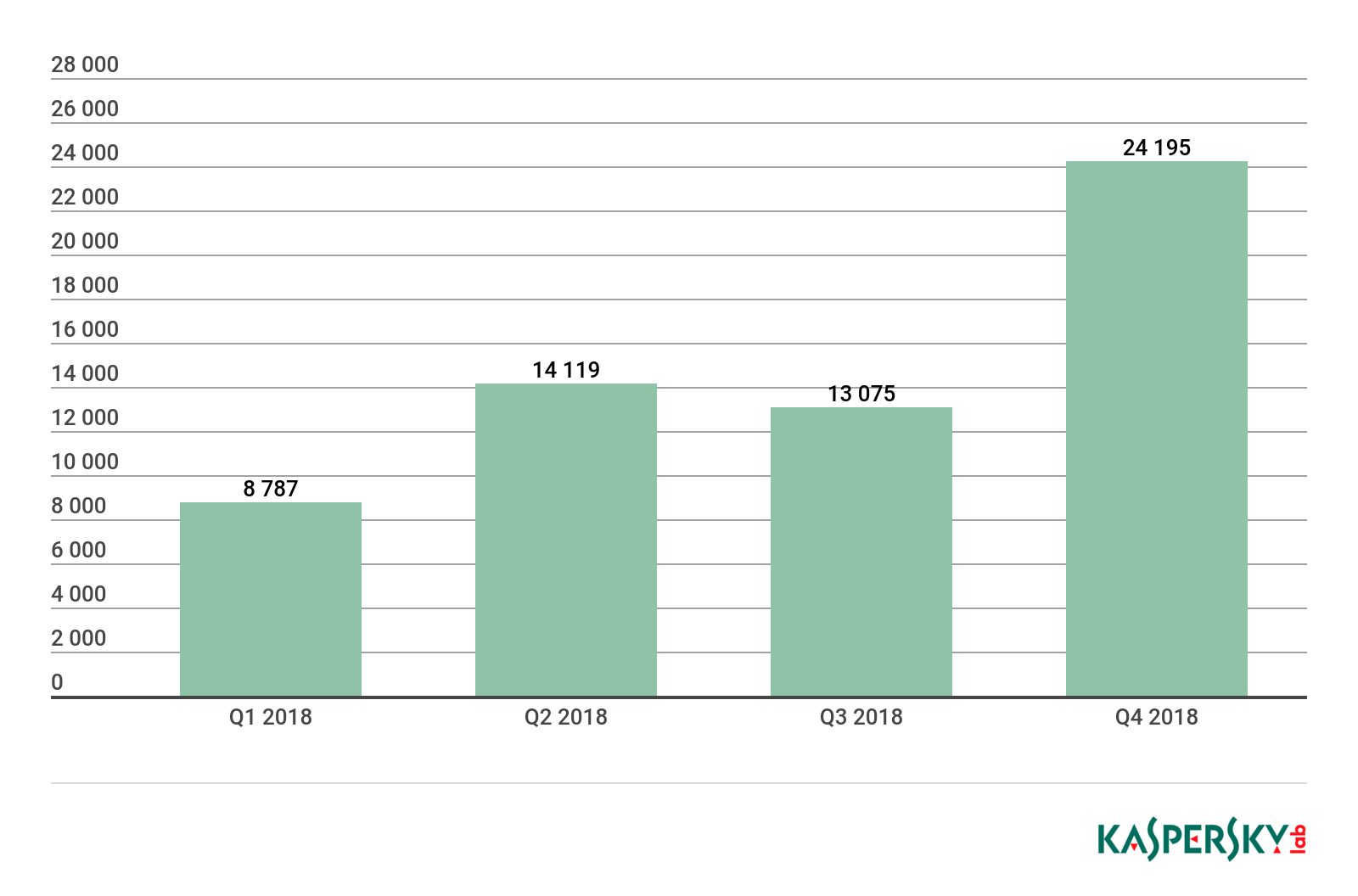

The statistics for Q1 2018 showed that the number of ransomware Trojans spreading without the assistance of droppers or downloaders had radically decreased. The reason for this was the ubiquitous use of a two-stage mechanism for distributing these malicious programs through Trojan droppers. A total of 60,176 mobile ransomware installation packages were detected throughout 2018, which is nine times less than in 2017.

Number of installation packages for mobile ransomware Trojans detected by Kaspersky Lab, 2018

The number of attacks involving mobile ransomware gradually declined over the first half of the year. However, June 2018 saw a sharp increase in the number of attacks, almost 3.5-fold.

Number of attacks by mobile ransomware Trojans, 2017 and 2018

In 2018, Kaspersky Lab products protected 80,638 users in 150 countries against mobile ransomware.

Countries by share of users attacked by mobile ransomware, 2018

Top 10 countries by share of all users attacked by mobile ransomware

| Country* | %** |

| US | 1.42 |

| Kazakhstan | 0.53 |

| Italy | 0.50 |

| Poland | 0.49 |

| Belgium | 0.37 |

| Ireland | 0.36 |

| Austria | 0.28 |

| Romania | 0.27 |

| Germany | 0.26 |

| Switzerland | 0.22 |

* Excluded from the rating are countries with fewer than 25,000 active users of Kaspersky Lab mobile solutions over the reporting period.

** Unique users attacked by mobile ransomware in the country as a percentage of all users of Kaspersky Lab mobile solutions in the country.

For the second year running, the country most under attack from mobile ransomware was the US, where 1.42% of users encountered it. As in the previous year, members of the Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Svpeng family were the most common ransomware Trojans in the country.

In second-place Kazakhstan (0.53%), the most active ransomware familes were Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Small and Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Rkor. The latter is not unlike other ransomware in that it shows victims an indecent picture and accuses them of viewing illegal materials.

In actual fact, the Trojan does not carry off any personal data or “suspend the servicing of the device”, as the warning claims. But the process of removing malware from an infected device can be difficult.

Conclusion

For seven years now, the world of mobile threats has been constantly evolving, not only in terms of number of malicious programs and technological refinement of each new malware modification, but also due to the increasing ways in which money and valuable information can be acquired using mobile devices. The year 2018 showed that a relative lull in certain types of malware can be followed by an epidemic. Last year, it was the banking Trojan Asacub and co.; in 2019 it could be a wave of ransomware, seeking to make up lost ground.

Mobile malware evolution 2018