Updated November 15th, 2011 (Scroll down to bottom)

This is an active investigation by Kaspersky Lab’s Global Research & Analysis Team. We will be updating this FAQ document as necessary.

What exactly is Duqu? How is it related to Stuxnet?

Duqu is a sophisticated Trojan which seems to have been written by the same people who created the infamous Stuxnet worm. Its main purpose is to act as a backdoor into the system and facilitate the theft of private information. This is the main difference when compared to Stuxnet, which was created to conduct industrial sabotage. It’s also important to point out that while Stuxnet is able to replicate from one computer to another using various mechanisms, Duqu is a Trojan that doesn’t seem to replicate on its own.

Does this target any PLC/SCADA equipment? Exactly who/what are the targets? Do we know?

Unlike Stuxnet, Duqu doesn’t target PLC/SCADA equipment directly, although some of its subroutines could be used to steal information related to industrial installations. It appears that Duqu was created in order to collect intelligence about its targets, which can include pretty much anything that is available in digital format on the victim’s PC.

How does Duqu infect computers? Can it spread via USB devices?

In the cases we have analysed, Duqu infects a computer through a targeted attack involving a Word document which exploits the CVE-2011-3402 vulnerability. This is a 0-day vulnerability in the Windows kernel component Win32k.sys which allows the attackers to run code with the highest privilege level, bypassing pretty much most of the protection mechanisms from Windows or security software. According to our knowledge, Duqu is the only malware using this vulnerability to infect computers. All Kaspersky Lab security solutions detect this vulnerability under the name Exploit.Win32.CVE-2011-3402.a as of November 6, 2011.

Is there any exploit, especially zero-day in Duqu?

There is indeed a 0-day vulnerability being used to infect computers in the initial phase. Microsoft released an advisory (2639658) with basic information and mitigation steps.

How did AV vendors become aware of this threat? Who reported it?

Duqu was brought to the attention of the security community by the Hungarian Research Lab CrySyS. They were the first to point out the resemblance to Stuxnet and perform what remains the most thorough analysis of the malware yet.

When was this threat first spotted?

The first Duqu attacks were spotted as early as mid-April 2011. The attacks continued in the following months, until October 18, when news about Duqu was made public.

How many variants of Duqu are there? Are there any major differences in the variants?

It appears that there are at least seven variants of the Duqu drivers, together with a few other components. These are all detected with different names by various anti-virus companies, creating the impression that there are multiple different variants. At the time of writing, we are aware of two Infostealer components and seven different drivers. Additionally, we suspect the existence of at least another Infostealer component which had the capability to directly search and steal documents from the victim’s machine.

There is talk that this specifically targets Certificate Authorities. Is this true?

While there are indeed reports indicating that the main goal of Duqu is to steal information from CAs, there is no clear evidence at this time to support this claim. On the contrary, we believe the main purpose of Duqu was different and CAs were just collateral victims.

Symantec says this is targeted to specific organizations, possibly with a view to collecting specific information that could be used for future attacks. What kinds of data are they looking for and what kinds of future attacks are possible?

One suspicion is that Duqu was used to steal certificates from CAs that can be used to sign malicious code in order to make it harder to catch. The functionality of the backdoor in Duqu is actually rather complex and it can be used for a lot more. Basically, it can steal everything, however, it looks like attackers were particularly interested in collecting passwords, making desktop screenshots (to spy on the user) and stealing various kinds of documents.

Is the command-and-control server used by Duqu still active? What happens when an infected machine contacts the C&C?

The initial Duqu C&C server, which was hosted in India is no longer active. Just like in the case of Stuxnet, it was pulled offline pretty quickly once the news broke. In addition to this, we are aware of another C&C server in Belgium, which was also quickly taken offline. Actually, it appears that every single Duqu targeted attack used a separate C&C server.

Why is Duqu configured to run for 36 days?

Maybe the author was a fan of round numbers, such as 6×6? 🙂 Actually, the time for which Duqu is running in the system is defined by the configuration file and varies between the attacks. We have also seen instances where the duration was set to 30 days.

Who is behind this attack?

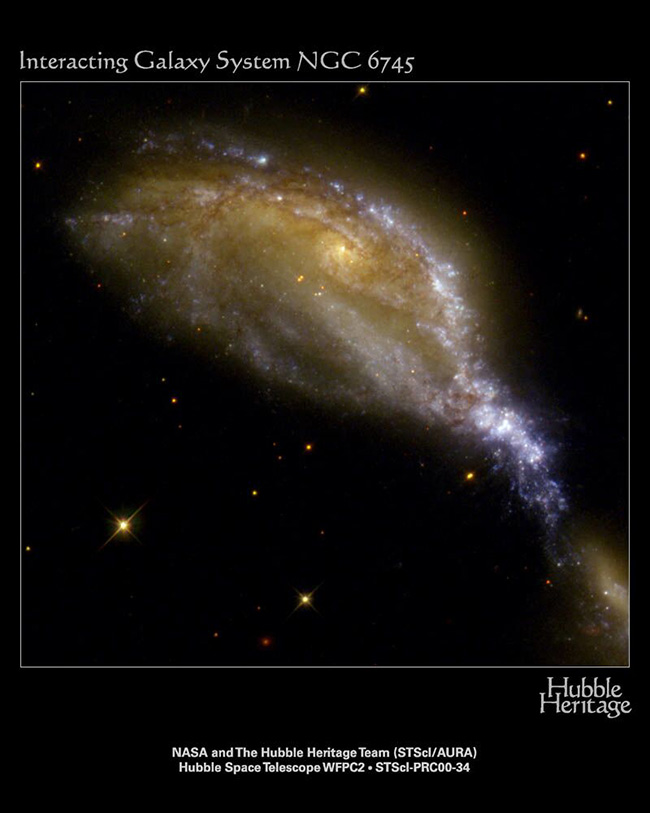

The same gang who was behind Stuxnet. Curiously, they seem to have picked up an interest in astronomy; the infostealer executable has a portion of a JPEG file picked up by the Hubble telescope (“Interacting Galaxy System NGC 6745”):

The picture portrays the aftermath of direct collision of two galaxies(!), several million of years ago. You can read the story here.

UPDATE (November 15, 2011):

Q: What exactly is being stolen from the target machines?

When activated, the main Duqu program body connects to its C&C server and downloads updates and supplemental modules. One such module is the Duqu “infostealer,” for which two versions are known and others are believed to have existed at various points in the time.

The “infostealer” module is downloaded in memory and executed through the process injection technique used by Stuxnet and Duqu to avoid temporary files. This is done in order to make sure that the “infostealer” component (and other Duqu updates) will not be intercepted or left behind on an infected machine. It also means that they have a limited lifetime, basically until the next system reboot.

The most powerful version of the “infostealer” has the ability to intercept keystrokes, it makes screenshots of the whole screen (first time) and of the active window, collects the IE browsing history and various data related to the system network configuration. There is also code which can do browsing of network shares. All this information is nicely packaged into a file that is written into the %TEMP% folder by default. It is a compressed BZIP2 format with modified headers. Thanks to the BZIP2 compression, the files are smaller than you’d think.

The “infostealer” components we have seen create files with the name “~DQx.tmp”. In addition to this, we are aware of other files with the name “~DFxxxxx.tmp” and “~DOxxxxx.tmp”. The “DF” and “DO” have a similar format and appear to have been generated by an earlier version of the “infostealer”. They also contain more information, including various files the victim PC such as Word or Excel documents. The “~DF” files are generally much bigger, due to their additional file content.

In all cases, they are easy to recognize by the header “ABh91AY&SY”. If you find such files in your PC then most likely you’ve been a victim of Duqu. If you’d like to scan your system for such files, the nice people at CrySyS have a set of tools that can help.

Q: I heard that Duqu and Stuxnet are written by the same people. I also heard that Duqu and Stuxnet are written by different people. What is the truth?

Duqu and Stuxnet have a lot of things in common. Usage of various encryption keys, including ones that haven’t been made public prior to Duqu, injection techniques, the usage of zero-day exploits, usage of stolen certificates to sign the drivers, all of these make us believe both have been written by the same team.

So, what does that mean exactly? Simply put, different people might have worked on Duqu and Stuxnet, but most likely they worked for the same “publishing house.” If you want an analogy, Duqu and Stuxnet are like Windows and Office. Both are from Microsoft, although different people might have worked on them.

Q: What is the link between Duqu and Showtime’s Dexter?

In the incidents we have analyzed, Duqu arrives in the system in the form of a Microsoft Word Document. The document contains an exploit for the vulnerability known as CVE-2011-3402. This is a buffer overflow in a function of Win32k.sys which deals with True Type fonts. To exploit this specific vulnerability, an attacker needs to craft a special True Type Font and embed it into a document, for instance, a Word Document.

Now, for the connection part – in the incident we’ve analyzed (and this is also true for the other known incident), the attackers used a font presumably called “Dexter Regular”, by “Showtime Inc.,” (c) 2003. This is another prank pulled by the Duqu authors, since Showtime Inc. is the cable broadcasting company behind the TV series Dexter, about a CSI doctor who also happens to be a serial killer who avenges criminals in some post-modern perversion of Charles Bronson’s character in Death Wish.

Q: So, are the Duqu authors sociopath serial killers with an interest in computer malware?

We hope they are just fans of Dexter.

Q: Stuxnet contains a particular variable which points to May 9, 1979, the date when a prominent Jewish businessman called Habib Elghanian was executed by a firing squad in Tehran. Are there such dates in Duqu as well?

Interestingly, the same constant can be found in Duqu as well. The Hungarian CrySyS lab was the first to point out the usage of 0xAE790509 in Duqu. In the case of Stuxnet, the integer 0x19790509 is used as an infection check; in the case of Duqu, the constant is 0xAE790509.

What is less known is that 0xAE790509 was also used in Stuxnet, however, prior to Duqu this was not included in any of the public analyses we are familiar with.

There are also many other places where the constant 0xAE is used, both in Duqu and Stuxnet.

Finally, the constant 0xAE240682 is used by Duqu as part of the decryption routine for one of the known PNF files. In case you are wondering, 24 June 1982 is indeed an interesting date – check out the case of BA flight 9.

* Research by Kaspersky Lab Global Research & Analysis Team.

Further reading:

- Part One. Connections between Duqu and Stuxnet. October 20th, 2011

- Part Two. One of the first real infection cases took place in Sudan. October 25th, 2011

- Part Three. Detection of the main missing link – a dropper that performed the initial system infection. November 02, 2011

- Part Four: Enter Mr. B. Jason and TV’s Dexter. Puzzles with a photo of the NGC 6745 galaxy and the TV series Dexter. November 11, 2011

- Part Five. Review of Duqu’s components. November 15, 2011

- Part Six. Researching the Command and Control infrastructure used by Duqu. November 30, 2011

- Part Seven. Stuxnet/Duqu: The Evolution of Drivers. December 28, 2011

- Part Eight. The mystery of the Duqu Framework

- Part Nine. The mystery of Duqu Framework solved

- Part Ten. The mystery of Duqu: Part Ten

Podcast

Costin Raiu of Kaspersky Lab’s Global Research and Analysis Team talks about the investigation into Duqu, the likelihood that it was written by the same team as Stuxnet, whether a government is behind its development and what mistakes the authors made.

Download the podcast from the Threatpost site.

Duqu FAQ