To complement the already mentioned findings, the same cybercriminal’s server contains additional interesting things but before mentioning them, I want to give a little bit more information about the email database used to spam victims to infect them with the Betabot malware.

E-mail database

How big is the list of email addresses to spam victims? It has 8,689,196 different addresses. It is a very complete database. Even if only 10% of the machines of the people included in this list get infected, cybercriminals would gain more than 800,000 infected PCs!

The geographic distribution of the emails is already published here. If we just look at the number of the most interesting domains belonging to governments, educational institutions and such used to spam and to infect, they are still very high numbers:

org 13772

edu 2015

gov 1575

gob 312

Spamming techniques

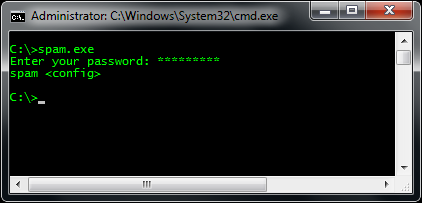

Most spam today is sent by botnets; however this is not what the gang behind this server is using. In this case, spam messages are sent via the app called “spam.exe”

[Path] / filename MD5 sum

——————————————————————————-

spam.exe dd77b464356a7c9de41377004dd1fa35

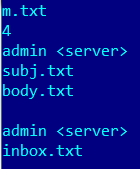

When it is running, it asks for the password (below) and then needs a special parameter, which is a plain text file.

![]()

The original parameter file is this one:

It accepts parameters like the number of threads, from, subject, body of the message, file to attach,reply-to and smtp server to use. There is a string inside of the compiled code pointing to the sources of the project:

j:hackdevspamspamobjReleasespam.pdb

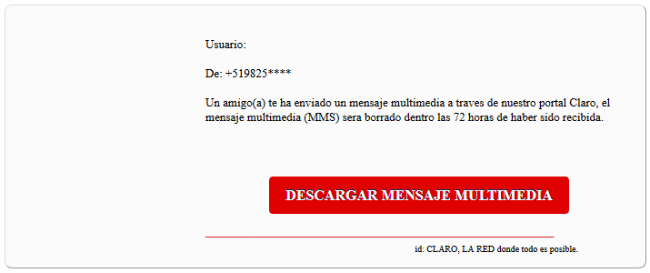

When this server was discovered, cybercriminals already had the next email ready to send to their victims:

The original malicious URL embedded into the message is this:

![]()

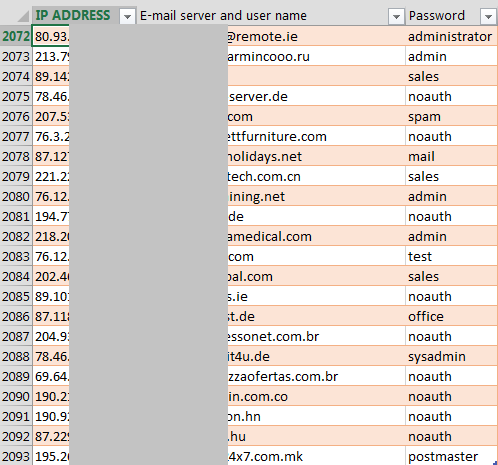

As I mentioned, the last parameter of “spam.exe” malicious mailer is the smtp server. Cybercriminals have collected 2,093 different not properly secured email servers around the world. This includes email servers from China, USA, Japan, Indonesia, Russia, Italy, Romania, Netherlands, Germany, Belorussia, Kazakhstan, Vietnam, Hong Kong, Ireland, Brazil, Greece, Chile, Czech Republic, Belgium, Philippines, Denmark, Sweden, Ukraine, Hungary, Canada, Malaysia, Poland, Peru, Taiwan, France, Korea, Spain and many others.

How did cybercriminals get so many misconfigured servers from around the world?

KISS

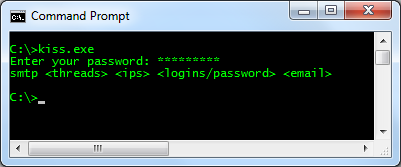

This is the name of the module used to attempt smtp servers if these have default accounts with the same default passwords. In other words, it is a brute force application to test smtp connections.

[Path] / filename MD5 sum

——————————————————————————-

kiss.exe 3a5d79a709781806f143d1880d657ba2

This is an app built inside of the same project; the string from the code confirms it:

J:hackdevbrutobjx86Releasekiss.pdb

Once running, it asks for the password, which is the same as for the “spam.exe” application. It accepts four parameters: threads, ips, logins/password and email.

When I found these resources, cybercriminals had in the IPS parameter file 1,519,403 IP addresses in queue to brute force!

![]()

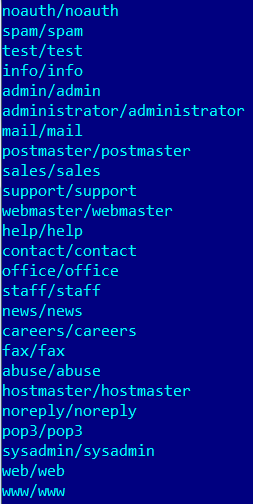

While the list of logins/passwords had the next combinations:

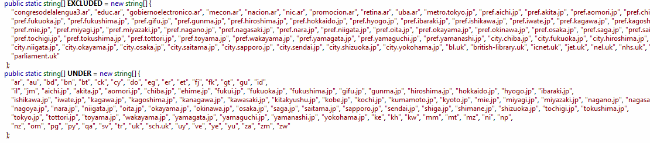

One interesting thing is that cybercriminals did not want to brute-force all and any domains so they included an exclusion list, which allows “kiss.exe“, to skip and not to brute-force the next domains:

Domains excluded from brute-forcing

Looks like they just did not want to attract too much attention, especially from governments, while brute-forcing.

Did I find other interesting things on that server? Yes, and I will post that in the next and last part of the series Big Box Latam Hack.

Kaspersky Anti-Virus detects “spam.exe” and “kiss.exe” as Email-Flooder.MSIL.Agent.r andHackTool.MSIL.BruteForce.ba respectively.

Conclusions

Cybercriminals from different regions may operate in a similar but yet different ways. This case is a good example as it shows how cybercriminals from Latin America, with no access to zombie machines, tried to find as many weak configured smtp servers as possible all around the world to distribute spam. This technique did not decrease their potential reach in terms of the number of victims nor their geographic location. Sometimes simple “solutions” work efficiently and we – as researchers – do not only have to focus on botnet-like activities.

As mentioned in the previous post, there is evidence cybercriminals from South America are in touch with cybercriminals from Eastern Europe and the worst part is that they are using mixed techniques: some codes from their European counterparts with others that are locally developed.

You may follow me on twitter: @dimitribest

Big Box LatAm Hack (2nd part – Email Brute-force and Spam)