Introduction

The Brazilian criminal underground includes some of the world’s most active and creative perpetrators of cybercrime. Like their counterparts in China and Russia, their cyberattacks have a strong local flavor. To fully understand them you need spend time in the country and understand its language and culture.

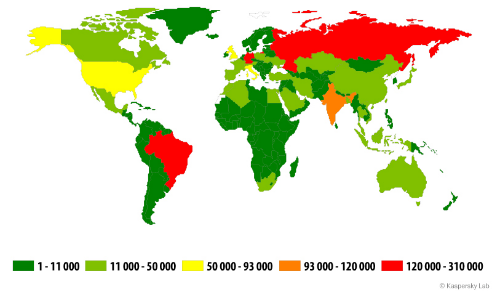

The Brazilian underground generates quite a lot of cyberthreats – mainly banking Trojans and phishing campaigns. These attacks can be quite creative and are designed to reflect the local landscape. In 2014, Brazil was ranked the most dangerous country for financial attacks, and the Brazilian banking Trojan, the ChePro family, was ranked the second most widespread Trojan after ZeuS.

Countries most affected by banking Trojans in 2014

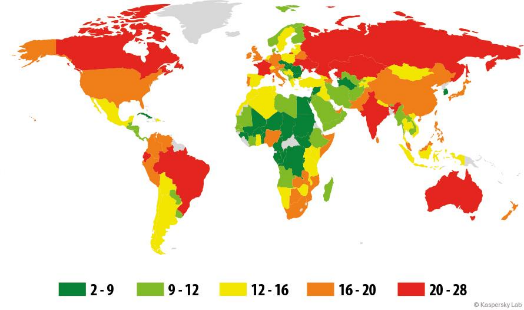

The picture for phishing attacks is not that different, with Brazil also ranked in first place worldwide. Not surprisingly, quite a number of the brands and companies that feature in the most frequently attacked list are Brazilian.

Countries most attacked by phishing attacks in 2014

Brazilian cybercriminals are adopting techniques that they have imported from Eastern Europe, inserting it into local malware to launch a series of geo-distributed attacks. These can include massive attacks against ISPs and modems and network devices or against popular, nationwide payment systems such as Boletos.

To understand what is going on in the Brazilian cybercriminal underground, we would like to take you on a journey into their world, to explore their attack strategy and their state of mind. We will look at the underworld market for stolen credit cards and personal data, the new techniques used in local malware and the ways in which they are cooperating with criminal in other countries.

For many people, Brazil is a country famous for its culture, beaches, samba and carnivals. For security professionals, it is equally renown as a prominent source of Banking Trojans.

Like Bonnie and Clyde: living the crazy life

The first impression you get is that Brazilian criminals like to flaunt how much money they have stolen and the high life they lead as a result of this. They compare themselves to Robin Hood: stealing from the ‘rich’ (in their eyes the banks, the financial systems and the government), in favor of the ‘poor’ (themselves). This is a widely-held conviction: they don’t regard themselves as stealing from individuals who bank online, but from the banks, since, according to local laws financial institutions are obliged to reimburse the victim for any money lost through theft.

There is a widespread sense of impunity, especially because, until recently cyber-crime was not legally defined as criminal activity under Brazilian law. The Carolina Dieckman law (named after a famous actress whose nude pictures were stolen from her computer) was approved in 2013, but the law is not very effective in punishing cybercriminals as the penalties are too lenient and the judicial system is very slow. It is very common for attackers to be arrested three or four times only to be released again without charge. The lack of effective legislation to combat cybercrime and high levels of police corruption provide the icing on the cake.

A strong indicator of just how immune to prosecution the cyber-criminals feel can be seen in the fact that it’s very easy to find videos and pictures of them online or to access their profiles on social networking sites. Invariably, they can be seen flaunting what appears to be stolen money, celebrating the high life, paying for prostitutes in Rio during the carnival, and more.

Brazil has achieved worldwide notoriety as a place where many ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ types are living decadent lives. How much do they steal? Quite a lot. According to the Brazilian Federation of Banks (FEBRABAN), in 2012 local banks lost 1.4 billion of reais (around US$500 million) paying for fraud perpetrated via Internet banking, by telephone, or through credit card cloning.

The target audience for cybercrime in Brazil is significant: the country has more than 100 million Internet users, 141 million citizens eligible to use Brazil’s e-voting system and more than 50 million people who use Internet banking services daily.

There are online videos celebrating the criminal life, like this song, the “Hacker’s Rap”. The lyrics celebrate the life of the criminals who use their knowledge to steal bank accounts and passwords:

The lyrics say: “I’m a virtual terrorist, a criminal; on the internet I spread terror, have nervous fingers; I’ll invade your PC, so heads up; you lose ‘playboy’, now your passwords are mine”.

Card-skimmers also celebrate and flaunt their profits in the “Cloned credit card rap”, also available on Youtube:

The lyrics include the words: “You work or you steal, we cloned the cards, I’m a 171, a professional fraudster and cloner, we steal from the rich, like Robin Hood, I’m a Raul…”

Recently the Brazilian Federal Police arrested the owner of a three million reais luxury mansion bought with funds stolen using Boleto malware. In Brazil, cybercrime pays, and pays very well.

C2C: Cybercrime to Cybercrime

As is the case with other underground fraternities, Brazilian cybercriminals are organized in small or medium-sized groups, each with their own expertise, selling their services to each other or working together. ‘Independent’ criminals are also common, but in general, most need to collaborate to do business.

The most common channels used by the Brazilian underworld to negotiate, buy and sell services or malware are Internet Relay Chat (IRC) channels. Some of them also use social networks such as Twitter and Facebook, but most of the juicy content is hidden inside IRC channels and closed forums that you can only join by invitation or with endorsement from an existing member. In these IRC chats criminals exchange data about attacks, hire out services among themselves, and sell personal data from hacked websites, while coders sell their malware and spammers sell their databases and services. These are true C2C (Cybercrime to Cybercrime) operations. The two most popular IRC networks used for such activity are FullNetwork and SilverLords.

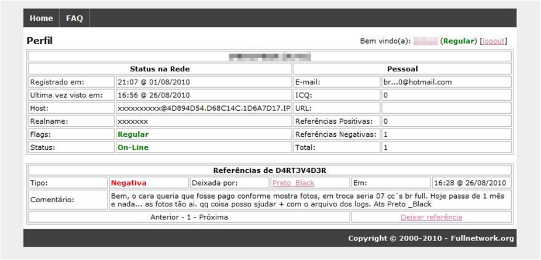

However, a very common problem among the criminal fraternity is what it calls “calote” or deadbeats – those people who steal from the thieves, who buy criminal services or software underground without paying the seller. Revenge is taken quickly and in one of two ways. Firstly, the bad player may be “doxed”: their real identity published with the aim of alerting Law Enforcement. Secondly, they may find their name added to a big reputation database of bad and good debtors. This ‘black’ and ‘white’ list enables the ‘community’ to protect itself by checking out the reputation of a customer before doing business with them.

An underground reputation system from Fullnetwork.org: protection against deadbeats

“Doxing” and other attacks on competing gangs are common among the Brazilian underground – some groups even celebrate the arrest of other cyber-crooks. That’s what happened with Alexandre Pereira Barros, responsible for the SilverLords network. He and three other cybercriminals were arrested by the Brazilian Federal Police in April 2013 after a series of fraud attacks against financial systems, credit card cloning, hacktivism attacks, and more. The group owned a lottery retailer in the state of Goias, responsible for theft of $250.000. To ‘celebrate’ their arrest, other criminals posted a video on Youtube, in revenge for unpaid debts:

Brazilian cybercriminals arrested in 2013 – unfortunately, they did not end up in jail after all

A typical Brazilian cybercrime group include four or five members, but some groups can be bigger than that. Each member has their own role. The main character in this scenario is the “coder”, the person responsible for developing the malware, buying exploits, creating a quality assurance system for the malware and building a statistical system that will be used by the group to count victims; and then putting everything in a package that can be easily negotiated and used by other criminals. Some coders don’t limit themselves to a single group and may work with several, and most prefer to not get their hands dirty with any stolen money. Their earnings come from selling their creations to other criminals. A coder could be a leader of a group, but this is not common. They are rarely arrested.

Every group has one or two spammers, responsible for buying mailing lists, buying VPSs and designing the “engenharia” (the social engineering used in the mail messages sent to the victims). Their role also involves spreading the infection as widely as possible. It´s common to find spammers with experience in the defacement of web servers that then allow them to insert a malicious iframe into infected websites. Spammers don’t have a fixed salary: their earnings come from the number of people infected. That is why the coder needs to build a victim-counter into the malware, as this information is used to calculate how much the spammer will receive.

The group also has a recruiter, responsible for hiring the money mules (also known as “laranjas”). This is a very important task because this person will be in direct contact with people or hold responsibility for external activities, such as for coordinating the things necessary for transferring the money or withdrawing it from ATMs, paying the bills (generally at a lottery house) or receiving the products bought online with the stolen credit cards – do the “correria” (foray). It´s common for the people in this role to recruit their own family members to work as money mules, as they can earn up to 30% of the sums stolen and distributed among the money mule accounts. Generally, the money mules are the first to be arrested in police operations, followed by the recruiter.

The real leader of the group is responsible for coordinating the other members and all the activites, negotiating new “KLs” (keyloggers) with a coder, requesting a new “engenharia” from the spammers, or do the “correria” with recruiters. They are also responsible for recruiting new members to the group and negotiating their wares in with other criminal groups. Roles are not fixed; some members may perform a number of functions and work with more than one group, and their earnings may vary. Some criminals prefer to work independently, selling their services and goodies to several groups.

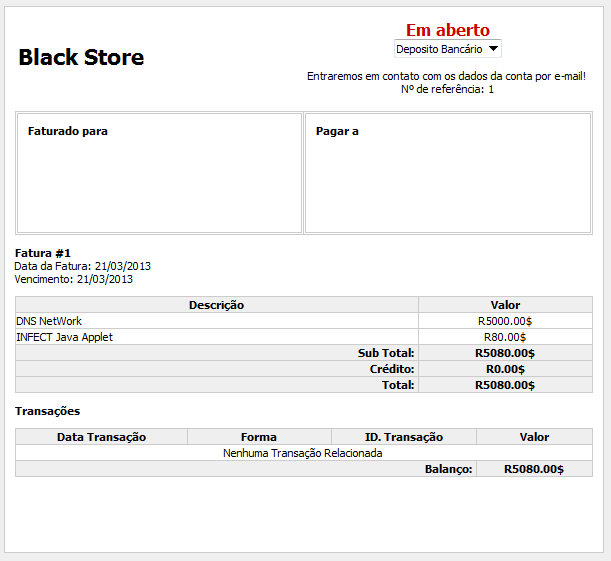

And some criminals have opened web stores to sell their goods and promote their services in a better and more user-friendly way. In these stores one can buy cryptors, hosting services, coding services for new Trojans, etc. That was the purpose of the “BlackStore” (now offline). Let’s check the prices of their ‘goodies’:

As a “professional” store, they also offer a receipt for your purchases:

Honest thieves: proof of your underground purchases

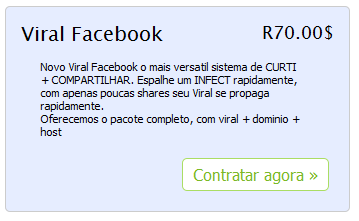

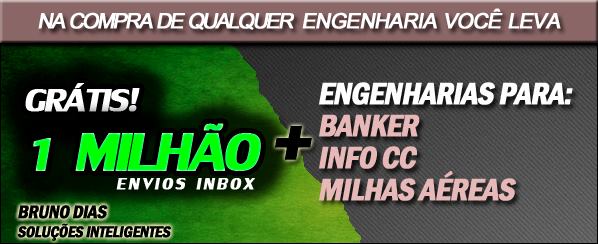

The professionalization of organized cybercrime, as observed in Eastern Europe, is now adopted by the Brazilian crime underground. Investment in technology and marketing is aimed at increasing their profits. In some closed forums criminals have even started advertising their services in a clear attempt to attract newcomers not used to developing their own tools:

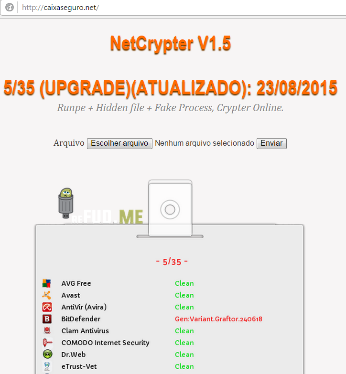

The text says: “Buying any social engineering kit you also earn kits for banker, credit card and frequent flyer miles. 1 million free spam messages, from Bruno Dias smart solutions”. Other services that are increasingly offered include websites offering “malware as service”, cryptors, FUDs (fully undetected malware) and a complete system to manage information about stolen banking accounts:

“FUD as a service”, encryption service for already detected trojans

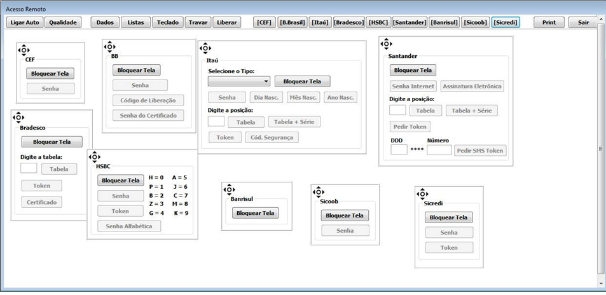

An “admin panel” manages the complete system that allow attackers to control infected machines, collect banking data, and bypass two-factor authentication (2FA) in any form (SMS, token, OTPs (one-time password cards) and more). Some systems also allow for the control of websites and domains used to spread the malware and to send spam and manage mail lists, all in a single solution.

Remote access tool sold on the underground intended to bypass the 2FA of Brazilian banks

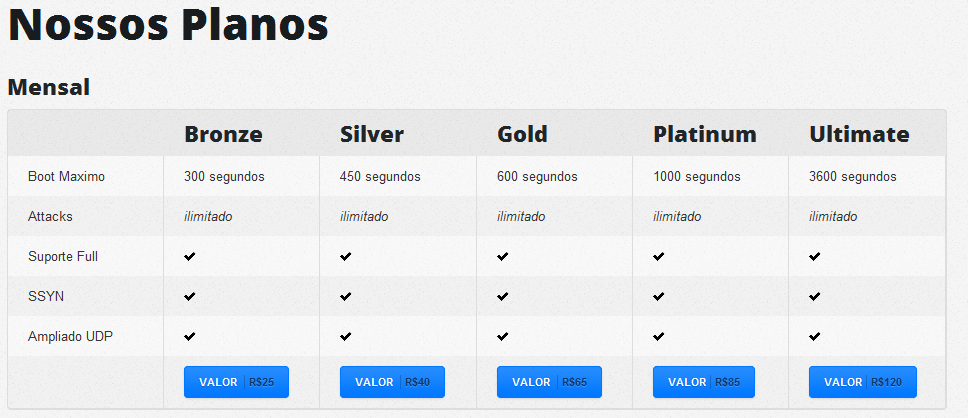

The goods on offer also include DDoS attacks. Using the power of thousands of infected computers it’s not difficult to perform a distributed denial of service for other criminals, using SYN flood, amplified UDP, and more. The prices are listed below: 300 seconds: $8.3; 450 seconds: $13; 1000 seconds: $28; 3600 seconds: $40.

DDoS for hire: takedown your target paying by seconds of attacks

How much does your credit card cost?

Credit card dumps are among the most valuable data exchanged among criminals. These have often been cloned in different ways, including chupa cabras (skimmers) on ATMs and point-of-sale terminals, phishing pages, keyloggers installed on victims’ PCs, and more.

Brazil has one of the highest concentrations of ATM terminals, according to the World Bank. There are more than 160,000 opportunities for fraudsters to install a skimmer (also known as a “Chupa Cabra device”), and they do this all the time. Even during the day you can see them hanging about, wearing flip-flops and beachwear and in a very relaxed mood, installing skimmers in a crowded bank:

When it comes to credit card cloning, Brazil has some of the most creative and active criminals. Fortunately, most of the cards in use have CHIP and PIN technology built in. Despite recent news revealing some security flaws in this protocol, CHIP and PIN cards are still more secure and harder to clone than magnetic swipe cards. Because these EMV chips are used all over the country, most of the cloning activity happens online, using phishing attacks, fake bank pages, fake giveaways and compromised e-commerce portals, offering an expensive product for very attractive price. If you are engaged in any type of online business, sooner or later your card will be attacked: via phishing or through compromise of the e-commerce portal.

These highly sought-after dumps are sold online through specialized websites or even through IRC channels. And it’s not just carders and cybercriminals who are involved in this underground business, but many ‘traditional’ criminals connected to drug trafficking and other illegal activities.

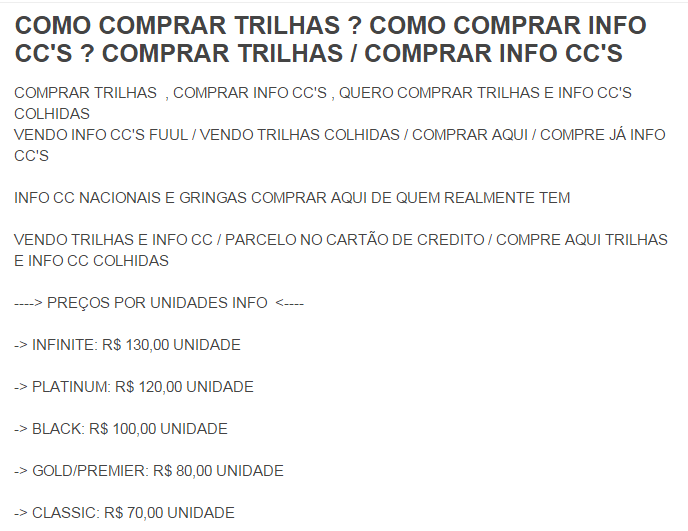

The price of a cloned credit card depends in the bank, the country of origin, etc.

- Infinity: flags such as American Express or international cards are sold at $42 apiece

- Platinum: cards from multinational banks, $40 apiece

- Black: cards by $30 apiece

- Gold/ Premier: $25 apiece

- Classic: from national banks, $22 apiece

Ad of a criminal selling dumps of stolen credit cards: you can even pay for it with your own credit card

Data breach incidents fueling cyberattacks

The Brazilian underground is hungry for personal data – and this allows cybercriminals to monetize identity theft, offering opportunities to buy products using “laranjas” or money mules, or even collect this data to empty your bank account, as several online services ask for personal data to confirm a customer’s identity.

Unfortunately, the country does not yet have specific laws in place to protect personal data – at this time politicians are still evaluating their options. As a result, data breaches in government organizations and private companies are widespread. Affected businesses currently are not obligated by law to contact customers affected by the breach or even to inform them that an incident has taken place.

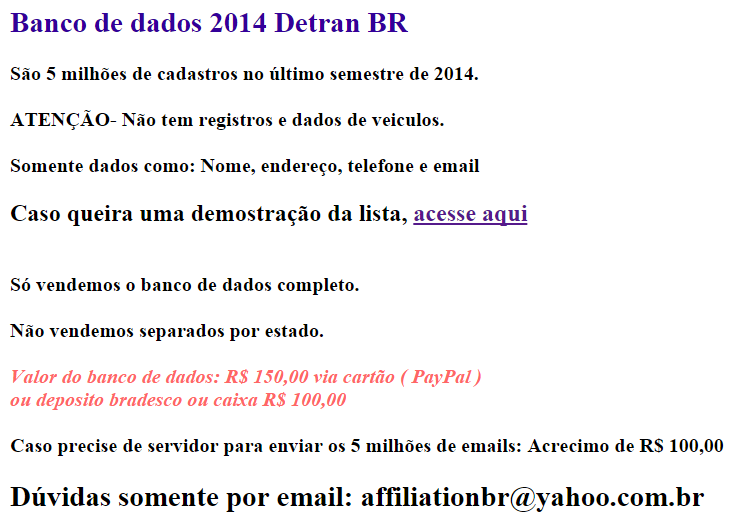

Recently, we observed some very serious data breach incidents affecting major websites, and involving databases from the government, Receita Federal (IRS) and other institutions. It is common to find leaked databases being sold underground, such as the database of DETRAN (Traffic Department), with data on five million citizens costing only US$50:

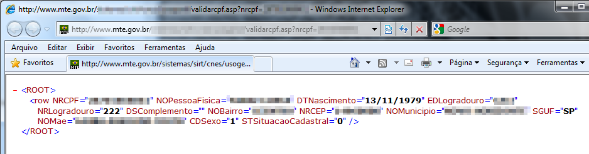

Flaws on government websites are critical. In 2011 two very serious flaws in the Labor Ministry website exposed an entire database with six months’ worth of data on every citizen in the country. A flaw in the website’s security left sensitive data out in the open, with only a CPF number (Brazilian SSN) required to obtain further information about a person.

The CPF is one of the most important documents for anyone living in Brazil. The number is unique and is a prerequisite for a series of tasks like opening bank accounts, to get or renew a driver’s license, buy or sell real estate, obtain loans, apply for a jobs (especially in the public sector), and to get a passport or credit cards. Leaked data makes it possible for a cybercriminal to impersonate the victim and to steal their identity in order to, for example, get a loan from a bank.

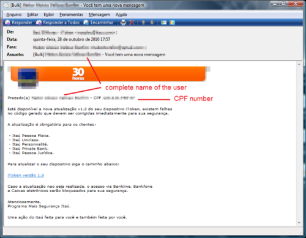

This is a case of where a data leak meets the phishers. Information of such quality can only be obtained through data leak incidents. Not surprisingly, it is common for the Brazilian media to spot criminals selling CDs carrying data from the Brazilian IRS system which includes a lot of sensitive data, including the CPF numbers. You can find criminals selling CDs full of leaked database from several sources for a mere $100. As a result of such data breaches, Brazilian phishers have created attacks with messages displaying the complete name and the CPF number of the victim in an attempt to add legitimacy to a fake message. Attacks such this one have happened regularly since 2011:

A phishing message displaying the complete name of the victim and their CPF number

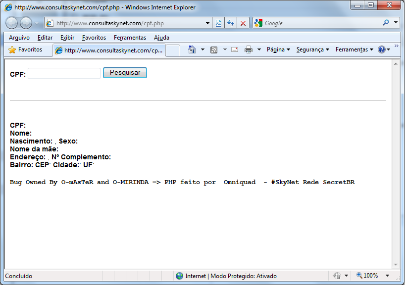

The abundance of personal data leaked from several sources has allowed Brazilian criminals to establish online services offering a searchable database with personal data from millions of citizens. Despite the efforts of the authorities to take down such websites, new services are created every month.

Having the CPF number is enough to find all your personal data

The problem of data brokers

Another problem related to the bad management of personal data is “Data brokers”, companies that collect information and then sell it on to companies that use it to target advertising and marketing at specific groups; or to verify a person’s identity for the purpose of fraud detection; or to sell to individuals and organizations so they can research particular individuals.

Local companies such as Serasa (now acquired by Experian) are a common target of phishers and malware authors. As they offer the biggest database in the country regarding fraud protection, and carry a complete profile of personal data for every citizen, the stolen credentials to access this database are valuable among fraudsters.

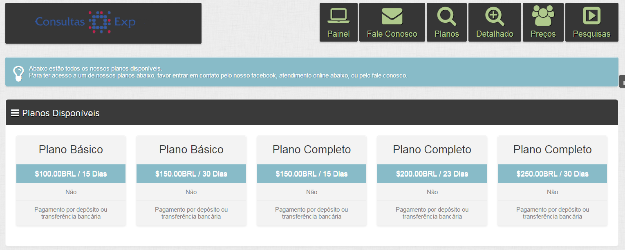

So, not surprisingly many fraudsters resell the results of their access to data broker services using stolen customer credentials, in packs that cost US$30 per 15 days or US$50 for 30 days of full access:

Other criminals go further, and build their own data broker services. Owners of these services market them to other fraudsters, offering a comprehensive package to search databases leaked from the government as well as those obtained from private sources. Such widespread activity gives the impression that in Brazil cybercrime will always be able to reach you, one way or another.

Govern and Data broker’s database together in the same underground service

To advertise their services, fraudsters use all channels, even social networks like Facebook. In a dossier published by Tecmundo they found evidence of public employees involved in the scheme, selling databases and credentials.

Access to stolen data service advertised on Facebook

How phishing attack compromised the Amazon forest

Could you imagine a phishing attack compromising the biggest rainforest in the world? That is what happened with IBAMA, the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources. IBAMA is responsible for limiting the cutting of hardwood trees in the Amazon region, ensuring that only authorized companies are able to do that.

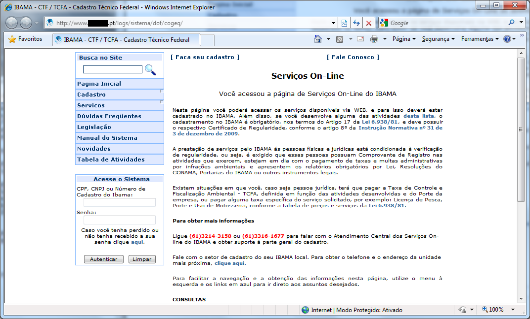

In a series of attacks against IBAMA’s employees (probably using phishing emails like the one below), Brazilian criminals were able to steal credentials and break into IBAMA’s online system. Then they unlocked 23 companies previously suspended for environmental crimes, allowing them to resume extracting wood from the forest. In just 10 days these companies extracted $11million in wood. The number of trees cut illegally was enough to fill 1,400 trucks.

Phishing page of IBAMA: to steal credentials and cut woods in the forest

Underground cooperation with Eastern Europe

We have sufficient evidence that Brazilian criminals are cooperating with the Eastern European gangs involved with ZeuS, SpyEye and other banking Trojans created in the region. This collaboration directly affects the quality and threat-level of local Brazilian malware, as its authors are adding new techniques to their creations.

It’s not unusual to find Brazilian criminals on Russian underground forums looking for samples, buying new crimeware and ATM/PoS malware, or negotiating and offering their services. The first result of this cooperation can be seen in the development of new attacks such the one affecting Boletos payments in Brazil.

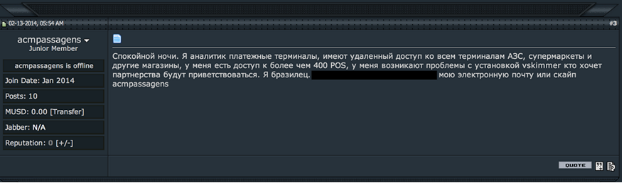

Brazilian bad guy writing in (very bad) Russian, selling access to 400 infected PoS devices

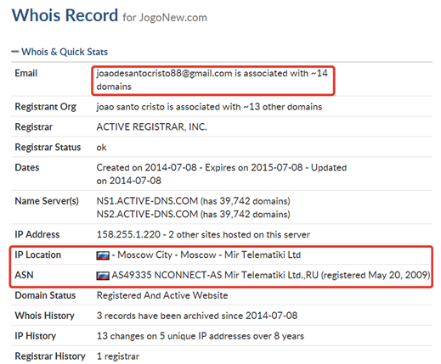

They have also started to use the infrastructure of Eastern European criminals, sometimes buying bulletproof hosting or renting it. “João de Santo Cristo” (a fictional character that appears in a popular Brazilian tune) was one of them, buying and hosting 14 Boleto malware domains in Russia:

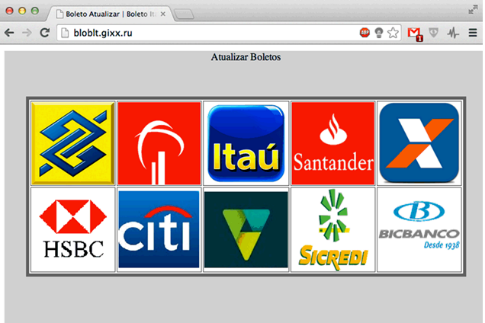

Not surprisingly we have started to see Russian websites hacked into and hosting fake Boleto websites:

These facts show how Brazilian cybercriminals are adopting new techniques as a result of collaboration with their European counterparts. We believe this is only the tip of the iceberg, as this kind of exchange tends to increase over the years as Brazilian crime develops and looks for new ways to attack businesses and regular people.

Advances in local malware

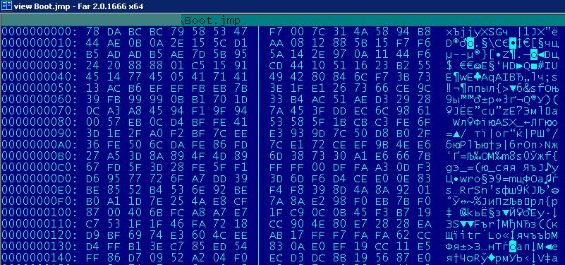

The contact with Eastern European cybercrime affects the quality of Brazilian malware. For example, we found in Boleto malware exactly the same encryption scheme that is used in payloads by ZeuS Gameover.

Encrypted payload of Boleto malware: the same encryption used by ZeuS

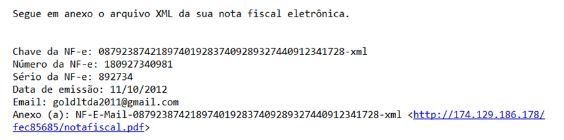

We also saw, for the first time, Brazilian malware using DGA (Domain Generation Algorithm). Trojan-Downloader.Win32.Crishi was one of them, distributed in messages like this one:

Further evidence of advances in Brazilian malware due to the cooperation with Eastern European criminals can be seen in the use of fast flux domains in Boleto attacks.

Conclusion

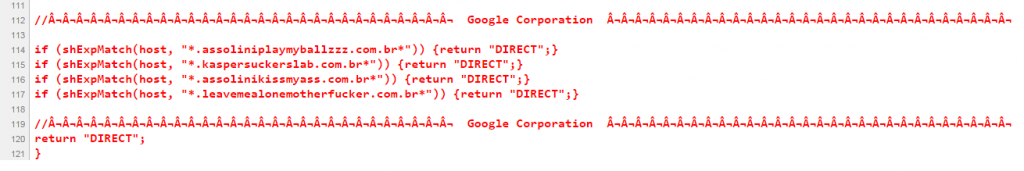

Brazil is one of the most dynamic and challenging markets in the world due to its particular characteristics and its important position in Latin America. The constant monitoring of Brazilian cybercriminals’ malicious activities provides IT security companies with a good opportunity to discover new attacks related to financial malware. In some cases these attacks are very unique as happened with the usage of malicious PAC files.

Message from bad guys in a malicious PAC file to yours truly: reaction due a good detection

To have a complete understanding of the Brazilian cybercrime scene, antimalware companies need to pay close attention to the reality of the country, collect files locally, build local honeypots, and retain local analysts to monitor the attacks, mostly because it’s common for criminals to restrict the reach of the infection and distribution of their creations to Brazilian users. As happens in Russia and China, Brazilian criminals have created their own, unique reality that’s very hard to understand from the outside.

Beaches, carnivals and cybercrime: a look inside the Brazilian underground

RaulB

The report is very interesting. Can add that some phishing campaigns in argentina seems to use Brazilian services as one can found coding with portuguese comments or variable names.

Limor

Total Deja vu… Everything we know from the underground replicated in Brazil. Interesting write up, enjoyed reading It.

Rastaman

With such an active underground, the 2016 Olympics will be a windfall for these crooks.