The concept of a connected car, or a car equipped with Internet access, has been gaining popularity for the last several years. The case in point is not only multimedia systems (music, maps, and films are available on-board in modern luxury cars) but also car key systems in both literal and figurative senses. By using proprietary mobile apps, it is possible to get the GPS coordinates of a car, trace its route, open its doors, start its engine, and turn on its auxiliary devices. On the one hand, these are absolutely useful features used by millions of people, but on the other hand, if a car thief were to gain access to the mobile device that belongs to a victim that has the app installed, then would car theft not become a mere trifle?

In pursuing the answer to this question, we decided to figure out what an evildoer can do and how car owners can avoid possible predicaments related to this issue.

Potential Threats

It should be noted that car-controlling apps are quite popular – most popular brands release apps whose number of users is between several tens of thousands and several million people. As an example, below are several apps listed with their total number of installations.

For our experiments, we took several apps that control cars from various manufacturers. We will not disclose the app titles, but we should note that we notified the manufacturers of our findings throughout our research.

We reviewed the following aspects of each app:

- Availability of potentially dangerous features, which basically means whether it is possible to steal a car or incapacitate one of its systems by using the app;

- Whether the developers of an app employed means to complicate reverse engineering of the app (obfuscation or packing). If not, then it won’t be hard for an evildoer to read the app code, find its vulnerabilities, and take advantage of them to get through to the car’s infrastructure;

- Whether the app checks for root permissions on the device (including subsequent canceled installations in case the permissions have been enabled). After all, if malware manages to infect a rooted device, then the malware will be capable of doing virtually anything. In this case, it is important to find out if developers programmed user credentials to be saved on the device as plain text;

- Whether there is verification that it is the GUI of the app that is displayed to the user (overlay protection). Android allows for monitoring of which app is displayed to the user, and a malware can intercept this event by showing a phishing window with an identical GUI to the user and steal, for instance, the user’s credentials;

- Availability of an integrity check in the app, i.e., whether it verifies itself for changes within its code or not. This affects, for example, the ability of a malefactor to inject his code into the app and then publish it in the app store, keeping the same functionality and features of the original app.

Unfortunately, all of the apps turned out to be vulnerable to attacks in one way or another.

Testing the Car Apps

For this study, we took seven of the most popular apps from well-known brands and tested the apps for vulnerabilities that can be used by malefactors to gain access to a car’s infrastructure.

The results of the test are shown in the summary table below. Additionally, we reviewed the security features of each of the apps.

| App | App features | App code obfuscation | Unencrypted username and password | Overlay protection for app window | Detection of root permissions | App integrity check |

| App #1 | Door unlock | No | Yes (login) | No | No | No |

| App #2 | Door unlock | No | Yes (login & password) | No | No | No |

| App #3 | Door unlock; engine start | No | – | No | No | No |

| App #4 | Door unlock | No | Yes (login) | No | No | No |

| App #5 | Door unlock; engine start | No | Yes (login) | No | No | No |

| App #6 | Door unlock; engine start | No | Yes (login) | No | No | No |

| App #7 | Door unlock; engine start | No | Yes (login & password) | No | No | No |

App #1

The whole car registration process boils down to entering a user login and password as well as the car’s VIN into the app. Afterwards, the app shows a PIN that has to be entered with conventional methods inside the car so as to finalize the procedure of linking the smartphone to the car. This means that knowing the VIN is not enough to unlock the doors of the car.

The app does not check if the device is rooted and stores the username for the service along with the VIN of the car in the accounts.xml file as plain text. If a Trojan has superuser access on the linked smartphone, then stealing the data will be quite easy.

App #1 can be easily decompiled, and the code can be read and understood. Besides that, it does not counter the overlapping of its own GUI, which means that a username and password can be obtained by a phishing app whose code may have only 50 lines. It should be enough to check which app is currently running and launch a malicious Activity with a similar GUI if the app has a target package name.

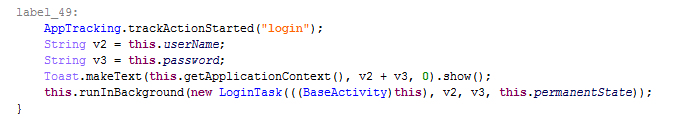

In order to check for integrity verification, we modified the loginWithCredentials method.

In this case, a username and password will simply be shown on the screen of a smartphone, but nothing prevents embedding a code to send credentials to a criminal’s server.

The absence of integrity verification allows any interested individual to take the app, modify it at his own discretion, and begin distributing it among potential victims. Signature verification is sorely lacking. There is no doubt that such an attack will require an evildoer to make some effort – a user has to be conned into downloading the modified version of the app. Despite that, the attack is quite surreptitious in nature, so the user will not notice anything out of the ordinary until his car has been stolen.

What is nice, however, is that the app pulls SSL certificates to create a connection. All in all, this is reasonable enough, as this prevents man-in-the-middle attacks.

App #2

The app offers to save user credentials but at the same time recommends encrypting the whole device as a precaution against theft. This is fair enough, but we are not going to steal the phone – we are just “infecting” it. As a result, there is the same trouble as found in App #1: the username and password are stored as plain text in the prefs file.{?????????}.xml file (the question marks represent random characters generated by the app).

The VIN is stored in the next file.

The farther we go, the more we get. The developers did not even find time to implement integrity verification of the app code, and, for some reason, they also forgot about obfuscation. As a consequence of that, we easily managed to modify the LoginActivity code.

Thus, the app preserved its own functionality. However, the username and password that had been entered during registration were displayed on the screen immediately after a login attempt.

App #3

Cars paired to this app are optionally supplied with a control module that can start the engine and unlock the doors. Every module installed by the dealer has a sticker with an access code, which is handed over to the car owner. This is why it is not possible to link the car to other credentials, even if its VIN is known.

Still, there are other attack possibilities: first, the app is tiny, as its APK size amounts to 180 kilobytes; secondly, the entire app logs its debugging data onto a file, which is saved on an SD card.

Logging at the start of LoginActivity

The location for dumping the log file

It’s a bit of bad luck that logging is enabled only when the following flag is set up in the app: android:debuggable=”true”. The public version of the app does not have the flag for obvious reasons, but nothing can stop us from inserting it into the app. To do that, we shall use the Apktool utility. After launching the edited app and attempting to log in, the SD card of the device will create a marcsApp folder with a TXT file. In our case, the username and password of the account have been output into the file.

Of course, persuading the victim to remove the original app and install an identical one with the debugging flag is not that easy. Nevertheless, this shuffling can be performed, for example, by luring the victim to a website where the edited app and installation manual can be downloaded as a critical update. Empirically, virus writers are good at employing social engineering methods such as this one. Now, it isn’t a big deal to add to the app the ability to send a log file to a designated server or a phone number as an SMS message.

App #4

The app allows binding of the existing VIN to any credentials, but the service will certainly send a request to the in-dash computer of the car. Therefore, unsophisticated VIN theft will not be conducive to hacking the car.

However, the tested app is defenseless against overlays on its window. If, owing to that, an evildoer obtains the username and password for the system, then he will be able to unlock the doors of the car.

Regretfully enough, the app stores the username for the system as well as a plethora of other interesting data, such as the car’s make, the VIN, and the car’s number, as clear text. All of these are located in the MyCachingStrategy.xml file.

App #5

In order to link a car to a smartphone that has the app installed, it is necessary to know the PIN that will be displayed by the in-dash computer of the car. This means that, just like in the case with the previous app, knowing the VIN is not enough; the car must be accessed from the inside.

App #6

This is an app made by Russian developers, which is conceptually different from its counterparts in that the car owner’s phone number is used as authorization. This approach creates a fair degree of risk for any car owner: to initiate an attack, just one Android API function has to be executed to gain possession of the username for the system.

App #7

For the last app that we reviewed, it must be noted that the username and password are stored as plain text in the credentials.xml file.

If a smartphone is successfully infected with a Trojan that has superuser permissions, then nothing will hinder the effortless theft of this file.

Opportunities for Car Theft

Theoretically, after stealing credentials, an evildoer will be able to gain control of the car, but this does not mean that the criminal is capable of simply driving off with it. The thing is, a key is needed for a car in order for it to start moving. Therefore, after accessing the inside of a car, car thieves use a programming unit to write a new key into the car’s on-board system. Now, let us recall that almost all of the described apps allow for the doors to be unlocked, that is, deactivation of the car’s alarm system. Thus, an evildoer can covertly and quickly perform all of the actions in order to steal a car without breaking or drilling anything.

Also, the risks should not be limited to mere car theft. Accessing the car and deliberate tampering with its elements may lead to road accidents, injuries, or death.

None of the reviewed apps have defense mechanisms. Due credit should be given to the app developers though: it is a very good thing that not a single of the aforementioned cases uses voice or SMS channels to control a car. Nonetheless, these exact methods are used by aftermarket alarm-system manufacturers, including Russian ones. On the one hand, this fact does not come as a surprise, as the quality of the mobile Internet does not always allow cars to stay connected everywhere, while voice calls and SMS messages are always available, since they are basic functions. On the other hand, this creates supernumerary car security threats, which we will now review.

Voice control is handled with so-called DTMF commands. The owner literally has to call up the car, and the alarm system responds to the incoming call with a pleasant female voice, reports the car status, and then switches to standby mode, where the system waits for commands from the owner. Then, it is enough to dial preset numbers on the keypad of the phone to command the car to unlock the doors and start the engine. The alarm system recognizes those codes and executes the proper command.

Developers of such systems have taken care of security by providing an allowlist for phone numbers that have permission to control the car. However, nobody imagined a situation where the phone of the owner is compromised. This means that it is enough for a malefactor to infect the smartphone of a victim with an unsophisticated app that calls up the alarm system on behalf of the victim. If the speakers and screen are disabled at the same time, then it is possible to take full command of the car, unbeknownst to the victim.

Certainly though, not everything is as simple as it seems at first glance. For example, many car enthusiasts save the alarm-system number under a made-up name, i.e. a successful attack necessitates frequent interaction of the victim with the car via calls. Only this way can an evildoer that has stolen the history of outgoing calls find the car number in the victim’s contacts.

The developers of another control method for the car alarm system certainly have read none of our articles on the security of Android devices, as the car is operated through SMS commands. The thing is, the first and most common mobile Trojans that Kaspersky Lab faced were SMS Trojans, or malware that contains code for sending SMS surreptitiously, which was done through common Trojan operation as well as by a remote command issued by malefactors. As a result, the doors of a victim’s car can be unlocked if malware developers perform the following three steps:

- Go through all of the SMS messages on the smartphone to look for car commands.

- If the needed SMS messages have been located, then extract the phone number and password from them in order to gain access.

- Send an SMS message to the discovered number that unlocks the car’s doors.

All of these three steps can be done by a Trojan while its victim suspects nothing. The only thing that needs to be done, which malefactors are certainly capable of handling, is to infect the smartphone.

Conclusion

Being an expensive thing, a car requires an approach to security that is no less meticulous than that of a bank account. The attitude of car manufacturers and developers is clear: they strive to fill the market quickly with apps that have new features to provide quality-of-life changes to car owners. Yet, when thinking about the security of a connected car, its infrastructure safety (for control servers) and its interaction and infrastructure channels are not the only things worth considering. It’s also worth it to pay attention to the client side, particularly to the app that is installed on user devices. It is too easy to turn the app against the car owner nowadays, and currently the client side is quite possibly the most vulnerable spot that can be targeted by malefactors.

At this point, it should be noted that we have not witnessed a single attack on an app that controls cars, and none of the thousands of instances of our malware detection contain a code for downloading the configuration files of such apps. However, contemporary Trojans are quite flexible: if one of these Trojans shows a persistent ad today (which cannot be removed by the user himself), then tomorrow it can upload a configuration file from a car app to a command-and-control server at the request of criminals. The Trojan could also delete the configuration file and override it with a modified one. As soon as all of this becomes financially viable for evildoers, new capabilities will soon arrive for even the most common mobile Trojans.

Mobile apps and stealing a connected car

Calum

I think the reason there have been no attacks is twofold: Firstly, the difficulty of physically locating a car, even after hacking the owner’s phone. No point unlocking it unless you or a trusty accomplice are standing there.

Secondly, the difficulty of disposing of a stolen car. It can certainly be done, but it requires knowledge and effort.

the best defence will be that it is impossible to locate a car from hacking a phone, unless the phone contains a text message or email naming the car location in so many words…