How cyberspies achieve their goals by using cheap tools and careful aiming

We’re already used to the fact that complex cyberattacks use 0-day vulnerabilities, bypassing digital signature checks, virtual file systems, non-standard encryption algorithms and other tricks. Sometimes, however, all of this may be done in much simpler ways, as was the case in the malicious campaign that we detected a while ago – we named it ‘Microcin’ after microini, one of the malicious components used in it.

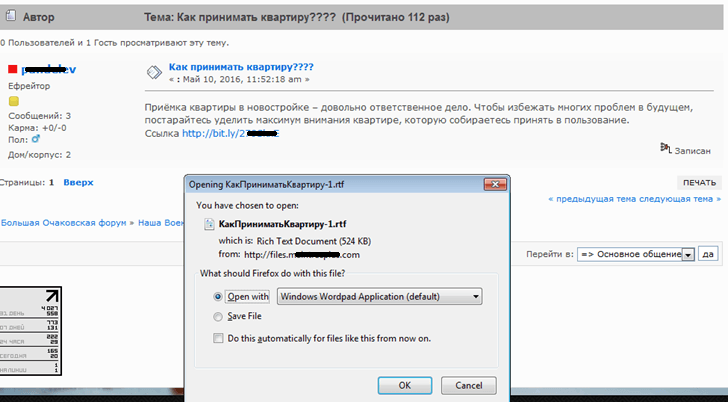

We detected a suspicious RTF file. The document contained an exploit to the previously known and patched vulnerability CVE-2015-1641; however, its code had been modified considerably. Remarkably, the malicious document was delivered via websites that targeted a very narrow audience, so we suspected early on that we were dealing with a targeted attack. The threat actors took aim at users visiting forums with discussions on the state-subsidized housing that Russian military personnel and their families are entitled to.

This approach appears to be very effective, as it substantially increases the chance that a potential victim will download and open the malicious document: the hosting forum is legitimate, and the malicious document is named accordingly (“Housing acceptance procedure” in Russian).

All links in the forum messages lead to the URL address files[.]maintr**plus[.]com, where the RTF document with the exploit was hosted. The threat actors sometimes used PPT files containing an executable PE file which did not contain the exploit, as the payload was launched by a script embedded into the PPT file.

If a Microsoft Office vulnerability is successfully exploited, the exploit creates an executable PE file on the hard drive and launches it for execution. The malicious program is a platform used to deploy extra (add-on) malicious modules, store them stealthily and thus add new capabilities for the threat actors. The attack unfolds in several stages, as described below:

- The exploit is activated, and an appropriate (32-bit or 64-bit) version of the malicious program is installed on the victim computer, depending on the type of operating system installed on it. To do this installation, malicious code is injected into the system process ‘explorer.exe’ rather than into its memory. The malicious program has a modular structure: its main body is stored in the registry, while its add-on modules are downloaded following the instruction arriving from the C&C server. DLL hijacking (use of a modified system library) is used to ensure that the main module is launched each time the system is rebooted.

- The main module of the malicious program receives an instruction to download and launch add-on modules, which opens new capabilities for the threat actors.

- The malicious add-on modules provide opportunities to control the victim system, take screenshots of windows and intercept information entered from the keyboard. We have seen them in other cyber-espionage campaigns as well.

- The threat actors use PowerSploit, a modified set of PowerShell scripts, and various utilities to steal files and passwords found on the victim computer.

The cybercriminals were primarily interested in .doc, .ppt, .xls, .docx, .pptx, .xlsx, .pdf, .txt and .rtf files on the victim computers. The harvested files were packed into a password-protected archive and sent to the threat actors’ server.

Overall, the tactics, techniques and procedures that the cybercriminals used in their attacks can hardly be considered complicated or expensive. However, there were a few things that caught our eye:

- The payload (at least one of the modules) is delivered using some simple steganography. Within traffic, it looks like a download of a regular JPEG image; however, the encrypted payload is loaded immediately after the image data. Microcin searches for a special ‘ABCD’ label in such a file; it is followed by a special structure, after which the payload comes, to be decrypted by Microcin. This way, new, platform-independent code and/or PE files can be delivered.

- If the Microcin installer detects the processes of some anti-malware programs running in the system, then, during installation, it skips the step of injecting into ‘explorer.exe’, and the modified system library used for establishing the malicious program within the system is placed into the folder %WINDIR%; to do this, the system app ‘wusa.exe’ is used with the parameter “/extract” (on operating systems with UAC).

Conclusion

No fundamentally new technologies are used in this malicious campaign, be it 0-day vulnerabilities or innovations in invasion or camouflaging techniques. The threat actors’ toolkit includes the following:

- A watering hole attack with a Microsoft Office exploit;

- Fileless storage of the main set of malicious functions (i.e., the shellcode) and the add-on modules;

- Invasion into a system process without injecting code into its memory;

- DLL hijacking applied to a system process as a means of ensuring automatic launch that does not leave any traces in the registry’s autorun keys.

The attackers also make use of PowerShell scripts that are used extensively in penetration tests. We have seen backdoors being used in different targeted attacks, while PowerSploit is an open-source project. However, cybercriminals can use known technologies as well to achieve their goals.

The most interesting part of this malicious campaign, in our view, is the attack vectors used in it. The organizations that are likely to find themselves on the cybercriminals’ target lists often do not pay any attention to these vectors.

First, if your corporate infrastructure is well protected and therefore ‘expensive’ to attack (i.e., an attack may require expensive 0-day exploits and other complicated tools), then the attackers will most likely attempt to attack your rank-and-file employees. This step follows a simple logic: an employee’s personal IT resources (such as his/her computer or mobile device) may become the ‘door’ leading into your corporate perimeter without the need of launching a direct attack. Therefore, it is important for organizations to inform their employees about the existing cyber threats and how they work.

Second, Microcin is just one out of a multitude of malicious campaigns that use tools and methods that are difficult to detect using standard or even corporate-class security solutions. Therefore, we recommend that large corporations and government agencies use comprehensive security solutions to protect against targeted attacks. These products are capable of detecting an ongoing attack, even if it employs only a minimum of manifestly malicious tools, as the attackers instead seek to use legal tools for penetration testing, remote control and other tasks.

The implementation of a comprehensive security system can substantially reduce the risk of the organization falling victim to a targeted attack, even though it is still unknown at the time of the attack. There is no way around it; without proper protection, your secrets may be stolen, and information is often more valuable than the cost of its reliable protection.

For more details of this malicious attack, please read Attachment (PDF).

A simple example of a complex cyberattack