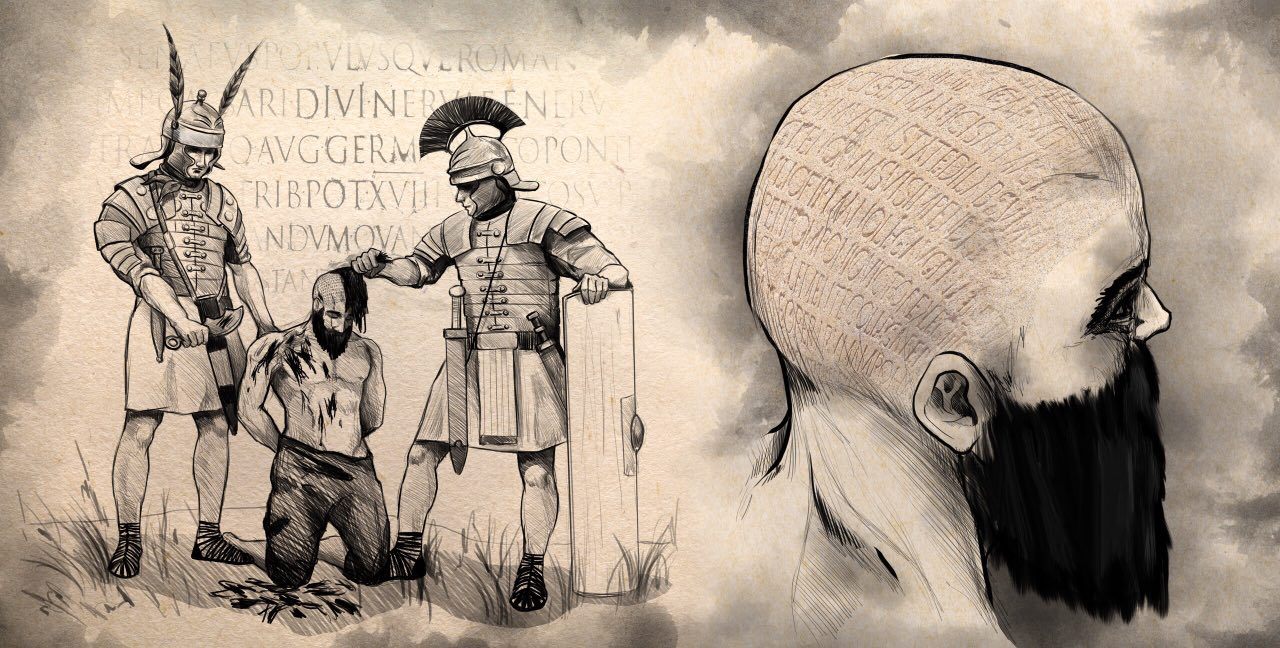

Steganography is the practice of sending data in a concealed format so the very fact of sending the data is disguised. The word steganography is a combination of the Greek words στεγανός (steganos), meaning “covered, concealed, or protected”, and γράφειν (graphein) meaning “writing”.

Unlike cryptography, which conceals the contents of a secret message, steganography conceals the very fact that a message is communicated. The concept of steganography was first introduced in 1499, but the idea itself has existed since ancient times. There are stories of a method being used in the Roman Empire whereby a slave chosen to convey a secret message had his scalp shaved clean and a message was tattooed onto the skin. When the messenger’s hair grew back, he was dispatched on his mission. The receiver shaved the messenger’s scalp again and read the message.

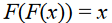

In this article, the following definitions are used:

- Payload: the information to be concealed and sent secretly, or the data covertly communicated;

- Carrier (stego-container): any object where the payload is secretly embedded;

- Stego-system: the methods and means used to create a concealed channel for communicating information;

- Channel: the data communication channel via which the carrier is transferred;

- Key: the key used to extract the payload from the carrier (not always applied).

Steganography was actively developed throughout the 20th century, as was steganalysis, or the practice of determining the fact that concealed information is being communicated within a carrier. (Basically, steganalysis is the practice of attacking stego-systems.) Today, however, a dangerous new trend is emerging: steganography is increasingly being used by actors creating malware and cyber-espionage tools. Most modern anti-malware solutions provide little, if any, protection from steganography, while any carrier in which a payload can be secretly carried poses a potential threat. It may contain data being exfiltrated by spyware, communication between a malicious program and its C&C, or new malware.

A variety of steganographic methods and algorithms have been scientifically developed and tested. A description of some of them is provided below.

- In LSB steganography, the payload is encoded into and communicated in one or several least significant bits of the carrier. The smaller the number of bits used to carry the payload, the lower the impact on the original carrier signal.

- Discrete cosine transform or DCT-based steganography is a sub-type of LSB steganography that is often applied on JPEG-format carriers (i.e., when JPEG images are used to carry the payload). In this method, the communicated data is secretly encoded into the DCT coefficients. With all other factors being equal, this method provides a somewhat lower data carrying capacity; one of the reasons for this is that the coefficient values of 0 and 1 cannot be altered, so no data can be encoded whenever the coefficients take on these values.

- Palette-based image steganography is basically another sub-type of LSB steganography, in which the communicated data is encoded into least significant bits of the image palette rather than into those of the carrier. The obvious downside to this method is its low data carrying capacity.

- Use of service fields in data formats. This is a relatively simple method, in which the payload is embedded into the service fields of the carrier’s headers. The downsides are, again, a low data carrying capacity and low payload protection: the embedded payload may be detected using regular image viewing software that can sometimes display the contents of the service fields.

- Payload embedding is a method whereby the payload is encoded into the carrier and, upon delivery, is decoded using an algorithm known to both parties. Several payloads can be independently encoded into the same carrier provided that their embedding methods are orthogonal.

- Wideband methods fall into the following types:

- Pseudorandom sequence method, in which a secret carrier signal is modulated by a pseudorandom signal.

- Frequency hopping method, in which the frequency of the carrier signal changes according to a specific pseudorandom law.

- Overlay method – strictly speaking, this is not proper steganography, and is based on the fact that some data formats contain data size in a header, or the fact that the handler of such formats reads the file till it reaches the end-of-data marker. An example is the well-known RAR/JPEG method based on concatenating an image file, so that it is composed of a JPEG format section, followed by a RAR archive section. A JPEG viewer software program will read it till the boundary specified in the file’s header, while a RAR archiver tool will disregard everything prior to the RAR! signature that denotes the beginning of an archive. Therefore, if such a file is opened in an image file viewer, it will display the image, and if it is opened in a RAR archiver, it will display the contents of the RAR archive. The downside to this method is that the overlay added to the carrier segment can be easily identified by an analyst visually reviewing the file.

In this article, we will only review methods of concealing information in image-type carriers and in network communication. The application of steganography is, however, much wider than these two areas.

Recently, we have seen steganography used in the following malware programs and cyberespionage tools:

- Microcin (AKA six little monkeys);

- NetTraveler;

- Zberp;

- Enfal (its new loader called Zero.T);

- Shamoon;

- KinS;

- ZeusVM;

- Triton (Fibbit).

So why are malware authors increasingly using steganography in their creations? We see three main reasons for this:

- It helps them conceal not just the data itself but the fact that data is being uploaded and downloaded;

- It helps bypass DPI systems, which is relevant for corporate systems;

- Use of steganography may help bypass security checks by anti-APT products, as the latter cannot process all image files (corporate networks contain too many of them, and the analysis algorithms are rather expensive).

For the end user, detecting a payload within a carrier may be a non-trivial task. As an example, let’s review the two images below. One is an empty carrier, and the other is a carrier with a payload. We will use the standard test image Lenna.

|

|

| Lenna.bmp | Lenna_stego.bmp |

Both images are 786 486 bytes; however, the right-hand image contains the first 10 chapters of Nabokov’s novel Lolita.

Take a good look at these two images. Can you see any difference? They are identical in both size and appearance. However, one of them is a carrier containing an embedded message.

The problems are obvious:

- Steganography is now very popular with malware and spyware writers;

- Anti-malware tools generally, and perimeter security tools specifically, can do very little with payload-filled carriers. Such carriers are very difficult to detect, as they look like regular image files (or other types of files);

- All steganography detection programs today are essentially proof-of-concept, and their logic cannot be implemented in commercial security tools because they are slow, have fairly low detection rates, and sometimes even contain errors in the math (we have seen some instances where this was the case).

A list was provided above (though it does not claim to be complete) of malicious programs that use steganography to conceal their communication. Let’s review one specific case from that list, the malicious loader Zero.T.

We detected this loader in late 2016, though our colleagues from Proofpoint were first to publish a description.

We named it Zero.T because of this string in its executable code (in the path leading to the project’s PBD file):

We will not dwell here on how the malicious loader penetrates the victim system and remains there, but will note that it loads a payload in the form of Bitmap files:

Then it processes them in a particular way to obtain malicious modules:

On the face of it, these three BMP files appear to be images:

|

|

|

However, they are more than just regular images; they are payload-filled carriers. In each of them, several (the algorithm allows for variability) least significant bits are replaced by the payload.

So, is there a way to determine whether an image is carrying a malicious payload or not? Yes, there are several ways of doing so, the simplest being a visual attack. It is based on forming new images from the source image, containing the least significant bits of different color planes.

Let’s see how this works using the Steve Jobs photo as a sample image.

We apply a visual attack to this image and construct new images from the separate significant bits in the appropriate order:

|

|

|

In the second and the third images, high entropy (high data density) areas are apparent – these contain the embedded payload.

Sounds simple, right? Yes and no. It’s simple in that an analyst – and even an average user – can easily see the embedded data; it’s difficult in that this sort of analysis is not easy to automate. Fortunately, scientists have long since developed a number of methods for detecting carriers with payloads, based on an image’s statistical characteristics. However, all of them are based on the assumption that the encoded payload has high entropy. This is true in most cases: since the container’s capacity is limited, the payload is compressed and/or encrypted before encoding, thus increasing its entropy.

However, our real-life example, the malicious loader Zero.T, does not compress its malicious modules before encoding. Instead, it increases the number of least significant bits it uses, which can be 1, 2 or 4. Yes, using a larger number of least significant bits introduces visual artefacts into the carrier image, which a regular user can detect visually. But we are talking about automatic analysis. So, the question we have to answer is: are statistical methods suitable for detecting embedded payloads with low levels of entropy?

Statistical methods of analysis: histogram method

This method was suggested in 2000 by Andreas Westfeld and Andreas Pfitzmann, and is also known as the chi-squared method. Below we give a brief overview.

The entire image raster is analyzed. For each color, the number of dots possessing that color is counted within the raster. (For simplicity, we are dealing with an image with one color plane.) This method assumes that the number of pixels possessing two adjacent colors (i.e. colors different only by one least significant bit) differs substantially for a regular image that does not contain an embedded payload (see Figure A below). For a carrier image with a payload, the number of pixels possessing these colors is similar (see Figure B).

|

|

| Figure A. An empty carrier | Figure B. A filled carrier. |

The above is an easy way to visually represent this algorithm.

Strictly speaking, the algorithm consists of the following steps that must be executed sequentially:

- The expected occurrence frequency for the pixels of color i in a payload-embedded image is calculated as follows:

- The measured frequency of the occurrence of a pixel of specific color is determined as:

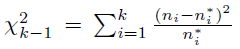

- The chi-squared criterion for k-1 degrees of freedom is calculated as:

- P is the probability that the distributions ni and ni* are equal under these conditions. It is calculated by integrating the density function:

Naturally, we have tested whether this method is suitable for detecting filled stego-containers. Here are the results.

| Original image | Visual attack image | Chi-squared attack, 10 zones |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The threshold values of the chi-squared distribution for p=0.95 and p=0.99 are 101.9705929 and 92.88655838 respectively. Thus, for the zones where the calculated chi-squared values are lower than the threshold, we can accept the original hypothesis “adjacent colors have similar frequency distributions, therefore we are dealing with a carrier image with a payload”.

Indeed, if we look at the visual attack images, we can clearly see that these zones contain an embedded payload. Thus, this method works for high-entropy payloads.

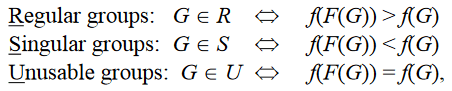

Statistical methods of analysis: RS method

Another statistical method of detecting payload carriers was suggested by Jessica Fridrich, Miroslav Goljan and Andreas Pfitzmann in 2001. It is called the RS method, where RS stands for ‘regular/singular’.

The analyzed image is divided into a set of pixel groups. A special flipping procedure is then applied for each group. Based on the values of the discriminant function before and after the flipping procedure is applied, all groups are divided into regular, singular and unusable groups.

This algorithm is based on the assumption that the number of regular and singular pixel groups must be approximately equal in the original image and in the image after flipping is applied. If the numbers of these groups change appreciably after flipping is applied, this indicates that the analyzed image is a carrier with a payload.

The algorithm consists of the following steps:

- The original image is divided into groups of n pixels (x1, …, xn).

- The so-called discriminant function is defined which assigns to each group of pixels G = (x1, …, xn) a real number f(x1, …, xn) ∈

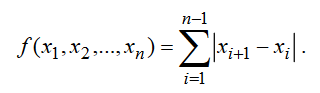

- The discriminant function for the groups of pixels (x1, …, xn) can be defined as follows:

- Then we define the flipping function which has the following properties:

Depending on the discriminant function’s values prior to and after flipping is applied, all groups of pixels are divided into regular, singular and unusable groups:

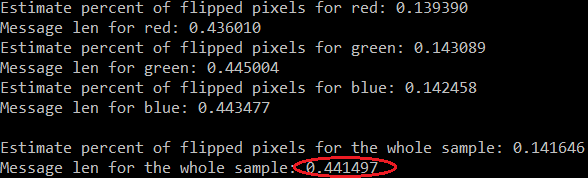

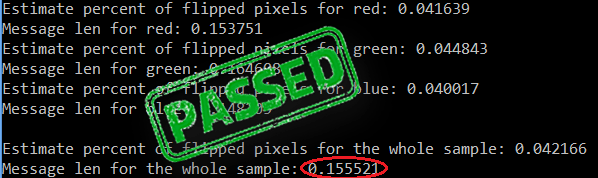

We have put this method to the test as well, and obtained the following results. We used the same empty and payload-embedded carriers as in the previous test.

| Original image | Visual attack image | Chi-squared attack, 10 zones |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note that this attack method does not pass the binary verdict in terms of “whether this specific carrier contains an embedded payload or not”; rather, it determines the approximate length of the embedded payload (as a percentage).

As can be seen from the results above, this method returned a verdict for the empty message that it was filled less than 1% with payload, and for the payload-embedded carrier it returned a verdict that it was about 44% filled. Obviously, these results are slightly off. Let’s look at the filled container: from the visual attack it follows that more than 50% of the container is filled, while the RS attack tells us that 44% of the container is filled. Therefore, we can apply this method if we establish a certain “trigger threshold”: our experiments showed that 10% is a sufficient threshold of reliability. If the RS attack claims that more than 10% of the container is full, you can trust this verdict and mark the container as full.

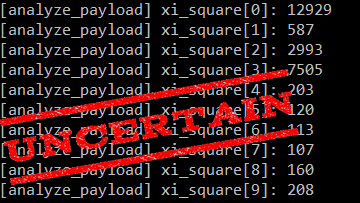

Now it’s time to test these two methods in real-world conditions, on the Zero.T carriers in which the payload has regular entropy.

We ran the appropriate tests and here are the results:

| Original image | Chi-squared attack | RS attack |

|

|

|

|

|

|

As we see, a chi-squared attack is not applicable on low entropy images – it yields unsatisfactory or inaccurate results. However, the RS attack worked well: in both cases, it detected a hidden payload in the image. However, what do we do if automatic analysis methods show there is no payload, but we still suspect there might be one?

In that case, we can apply specific procedures that have been developed for specific malware families to extract the payload. For the aforementioned Zero.T loader, we have written our own embedded payload extraction tool. Its operation can be schematically presented as follows.

|

+ |  |

| = | ||

|

||

Obviously, if we get a valid result (in this specific case, an executable file), then the source image has an embedded payload in it.

Is DNS tunneling also steganography?

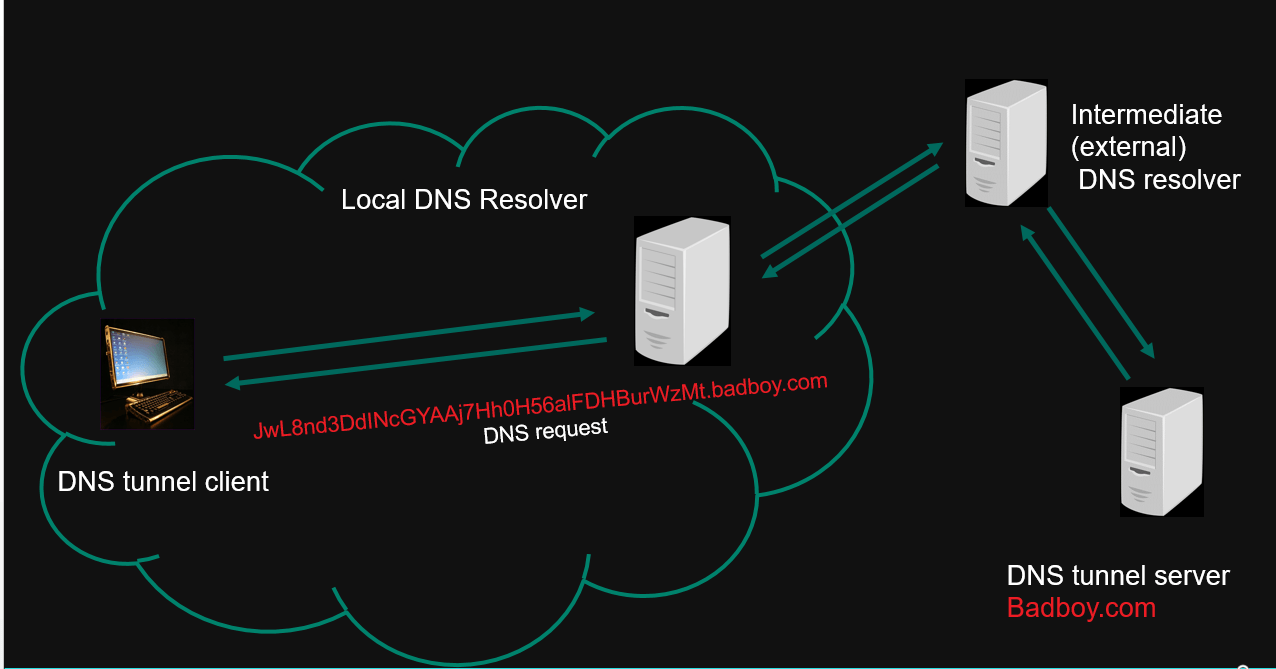

Can we consider use of a DNS tunnel a subtype of steganography? Yes, definitely. For starters, let’s recap on how a DNS tunnel works.

From a user computer in a closed network, a request is sent to resolve a domain, for example the domain wL8nd3DdINcGYAAj7Hh0H56a8nd3DdINcGYAlFDHBurWzMt[.]imbadguy[.]com to an IP address. (In this URL, the second-level domain name is not meaningful.) The local DNS server forwards this request to an external DNS server. The latter, in turn, does not know the third-level domain name, so it passes this request forward. Thus, this DNS request follows a chain of redirections from one DNS server to another, and reaches the DNS server of the domain imbadguy[.]com.

Instead of resolving a DNS request at the DNS server, threat actors can extract the information they require from the received domain name by decoding its first part. For example, information about the user’s system can be transmitted in this way. In response, a threat actor’s DNS server also sends some information in a decoded format, putting it into the third- or higher-level domain name.

This means the attacker has 255 characters in reserve for each DNS resolution, up to 63 characters for subdomains. 63 characters’ worth of data is sent in each DNS request, and 63 characters are sent back in response, and so on. This makes it a decent data communications channel! Most importantly, it is concealed communication, as an unaided eye cannot see that any extra data is being communicated.

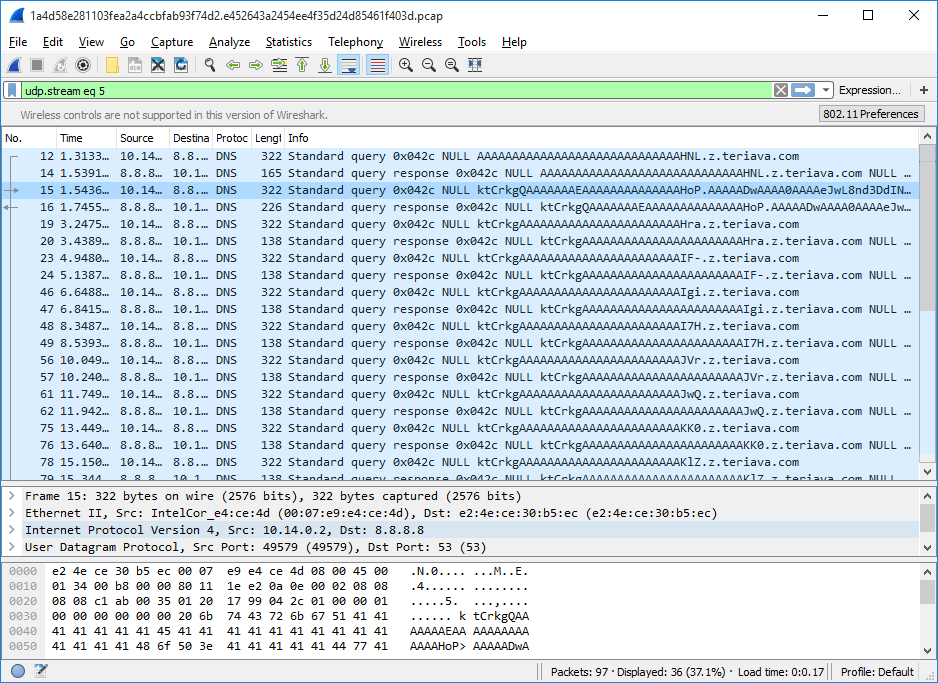

To specialists who are familiar with network protocols and, in particular, with DNS tunneling, a traffic dump containing this sort of communication will look quite suspicious – it will contain too many long domains that get successfully resolved. In this specific case, we are looking at the real-life example of traffic generated by the Trojan Backdoor.Win32.Denis, which uses a DNS tunnel as a concealed channel to communicate with its C&C.

A DNS tunnel can be detected with the help of any popular intrusion detection (IDS) tool such as Snort, Suiricata or BRO IDS. This can be done using various methods. For example, one obvious idea is to use the fact that domain names sent for DNS resolution are much longer than usual during tunneling. There are quite a few variations on this theme on the Internet:

alert udp any any -> any 53 (msg:”Large DNS Query, possible cover channel”; content:”|01 00 00 01 00 00 00 00 00 00|”; depth:10; offset:2; dsize:>40; sid:1235467;)

There is also this rather primitive approach:

Alert udp $HOME_NET and -> any 53 (msg: “Large DNS Query”; dsize: >100; sid:1234567;)

There is plenty of room for experimenting here, trying to find a balance between the number of false positives and detecting instances of actual DNS tunneling.

Apart from suspiciously long domain names, what other factors may be useful? Well, anomalous syntax of domain names is another factor. All of us have some idea of what typical domain names look like – they usually contain letters and numbers. But if a domain name contains Base64 characters, it will look pretty suspicious, won’t it? If this sort of domain name is also quite long, then it is clearly worth a closer look.

Many more such anomalies can be described. Regular expressions are of great help in detecting them.

We would like to note that even such a basic approach to detecting DNS tunnels works very well. We applied several of these rules for intrusion detection to the stream of malware samples sent to Kaspersky Lab for analysis, and detected several new, previously unknown backdoors that used DNS tunnels as a covert channel for C&C communication.

Conclusions

We are seeing a strong upward trend in malware developers using steganography for different purposes, including for concealing C&C communication and for downloading malicious modules. This is an effective approach considering payload detection tools are probabilistic and expensive, meaning most security solutions cannot afford to process all the objects that may contain steganography payloads.

However, effective solutions do exist – they are based on combinations of different methods of analysis, prompt pre-detections, analysis of meta-data of the potential payload carrier, etc. Today, such solutions are implemented in Kaspersky Lab’s Anti-Targeted Attack solution (KATA). With KATA deployed, an information security officer can promptly find out about a possible targeted attack on the protected perimeter and/or the fact that data is being exfiltrated.

Steganography in contemporary cyberattacks

Richard J. Barbalace

Thank you, Alexey and Evgeniya, for such an interesting and informative article. The methods you describe for detection of steganographic payloads are certainly valuable, but as someone who is not a professional security researcher, I also wonder about taking that a step further to develop methods for automatically disabling such payloads. What methods already exist for disabling an undetected payload?

As an example, let’s say an adversary might be trying to deliver such a payload in the least significant bits of a carrier image as described, but analyzing every image that enters a corporate network might be prohibitively expensive. would it be feasible to, say, zero all the least significant bits of all incoming images to eliminate the payload? Would this be possible without affecting image quality significantly? Would this be efficient? It might not even be necessary to zero all the least significant bits. Perhaps a switching of a small number of random bits throughout the image would be enough to disable an executable or DLL even if most of the payload were read, by introducing sufficient errors in the extracted code? Are techniques such as this or similar currently employed?

It strikes me that such a random disruption to a payload could work to defeat other steganographic techniques for delivering malicious malware, not just LSB methods, because executable code tends to be sensitive to small errors. In contrast, this would not work as well to disrupt covert messages meant to be read by humans, who would be able to understand a m3ss4ge with minor parts corrupted. What thoughts do you have on this general idea?

Jim

Fascinating, informative and do I have KATA installed or do I have to purchase it?