How a harmless-looking insider can compromise your network

How often do you turn off your computer when you go home from work? We bet you leave it on so you don’t have to wait until it boots up in the morning. It’s possible that your IT staff have trained you to lock your system for security reasons whenever you leave your workplace. But locking your system won’t save your computer from a new type of attack that is steadily gaining popularity on Raspberry Pi enthusiast forums.

We previously investigated the security of charging a smartphone via a USB port connection. In this research we’ll be revisiting the USB port – this time in attempts to intercept user authentication data on the system that a microcomputer is connected to. As we discovered, this type of attack successfully allows an intruder to retrieve user authentication data – even when the targeted system is locked. It also makes it possible to get hold of administrator credentials. Remember Carbanak, the great bank robbery of 2015, when criminals were able to steal up to a billion dollars? Finding and retrieving the credentials of users with administrative privileges was an important part of that robbery scheme.

In our research we will show that stealing administrator credentials is possible by briefly connecting a microcomputer via USB to any computer within the corporate perimeter. By credentials in this blogpost we mean the user name and password hash and we won’t go into detail how to decipher the retrieved hash, or how to use it in the pass-the-has types of attacks. What we’re emphasizing is that the hardware cost of such an attack is no more than $20 and it can be carried out by a person without any specific skills or qualifications. All that’s needed is physical access to corporate computers. For example, it could be a cleaner who is asked to plug “this thing” into any computer that’s not turned off.

We used a Raspberry Pi Zero in our experiments. It was configured to enumerate itself as an Ethernet adapter on the system it was being plugged into. This choice was dictated by the popularity of Raspberry Pi Zero mentions on forums where enthusiasts discuss the possibility of breaking into information systems with single-board computers. This popularity is understandable, given the device capabilities, size and price. Its developers were able to crank the chip and interfaces into a package that is slightly larger than an ordinary USB flash drive.

Yes, the idea of using microcomputers to intercept and analyze network packets or even as a universal penetration testing platform is nothing new. Most known miniature computing devices are built on ARM microprocessors, and there is a special build of Kali Linux that is specifically developed for pen testing purposes.

There are specialized computing sticks that are designed specifically for pen testing purposes, for example, USB Armory. However, with all its benefits, like integrated USB Type A connector (Raspberry Pi requires an adapter), USB Armory costs much more (around $135) and absolutely pales in comparison when you look at its availability vs. Raspberry Pi Zero. Claims that Raspberry Pi can be used to steal hashes when connected via USB to a PC or Mac surfaced back in 2016. Soon there were claims that Raspberry Pi Zero could also be used for stealing cookies fromh3 browsers – something we also decided to investigate.

So, armed with one of the most widespread and available microcomputers at the moment, we conducted two series of experiments. In the first, we attempted to intercept user credentials within the corporate network, trying to connect to laptop and desktop computers running different operating systems. In the second, we attempted to retrieve cookies in a bid to restore the user session on a popular website.

Experiment 1: stealing domain credentials

Methodology

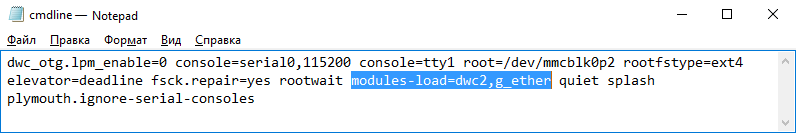

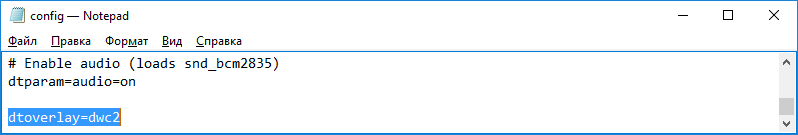

The key principle behind this attack is emulation of the network adapter. We had absolutely no difficulties in finding the module emulating the Ethernet adapter under Raspbian OS (for reference, at the time of writing, we hadn’t found a similar module for Kali Linux). We made a few configuration changes in the cmdline.txt and config.txt files to load the module on boot.

A few extra steps included installing the python interpreter, sqlite3 database library and a special app called Responder for packet sniffing:

apt-get install -y python git python-pip python-dev screen sqlite3

pip install pycrypto

git clone https://github.com/spiderlabs/responder

And that wasn’t all – we set up our own DHCP server where we defined the range of IP addresses and a mask for a subnet to separate it from the network we’re going to peer into. The last steps included configuring the usb0 interface and automatic loading of Responder and DHCP server on boot. Now we were ready to rock.

Results

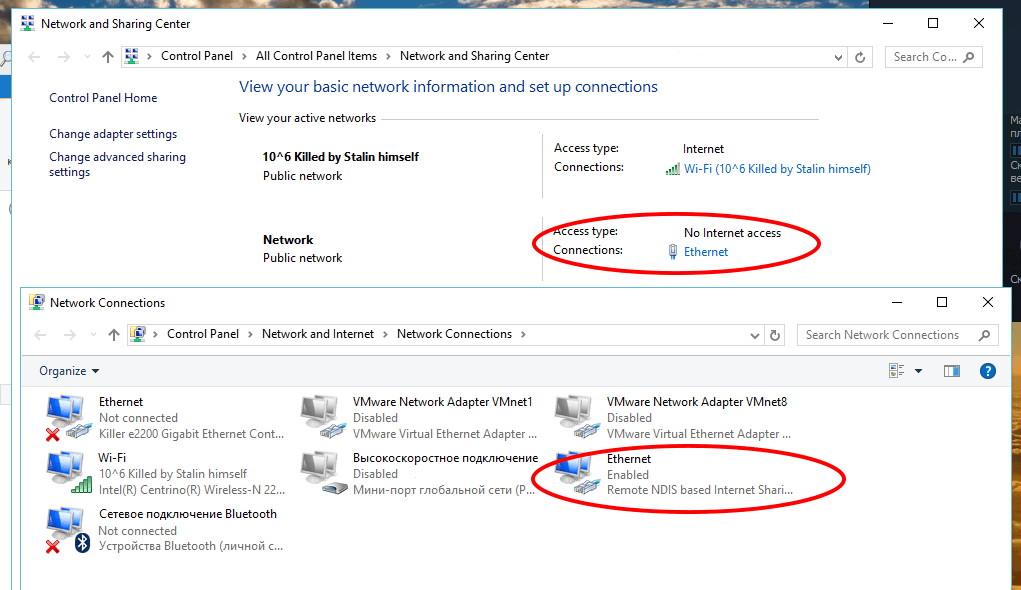

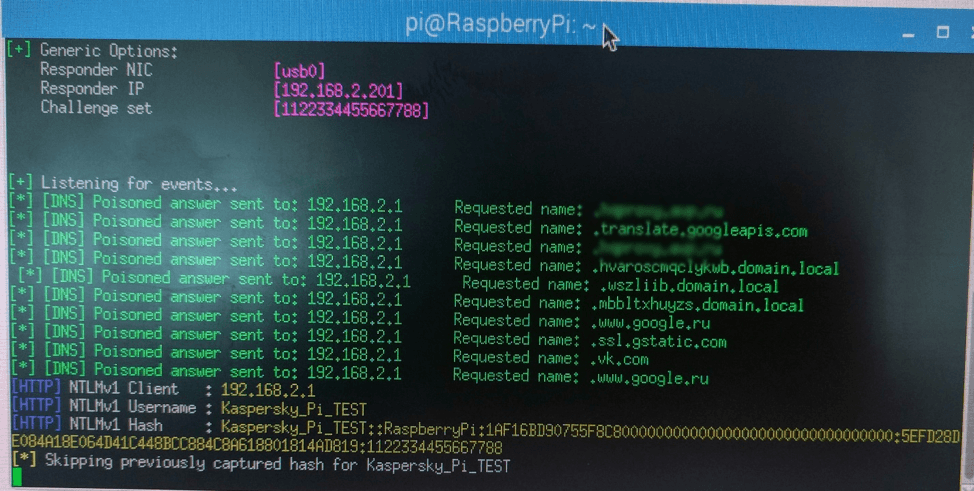

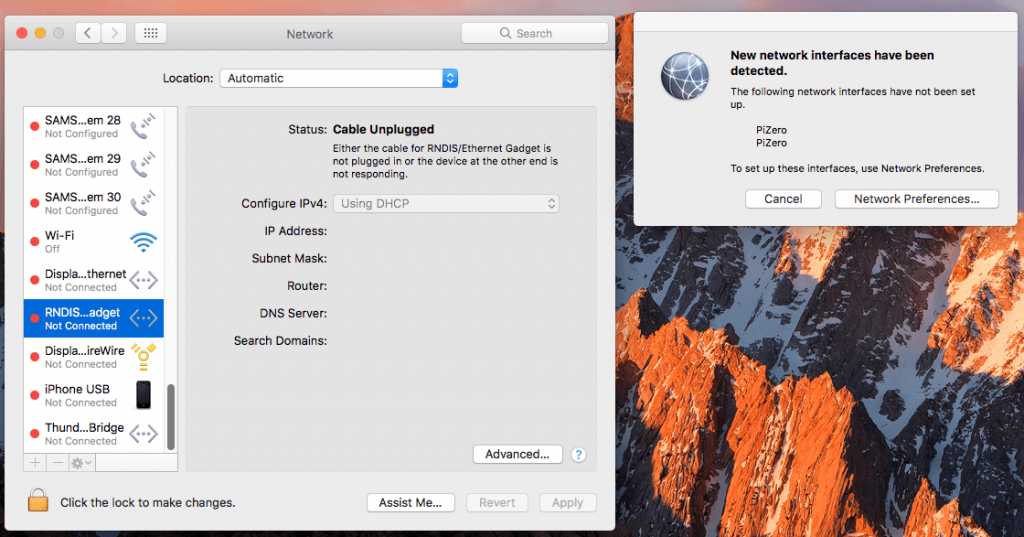

Just as soon as we connected our “charged” microcomputer to Windows 10, we saw that the connected Raspberry Pi was identified as a wired LAN connection. The Network Settings dialogue shows this adapter as Remote NDIS Internet sharing device. And it’s automatically assigned a higher priority than others.

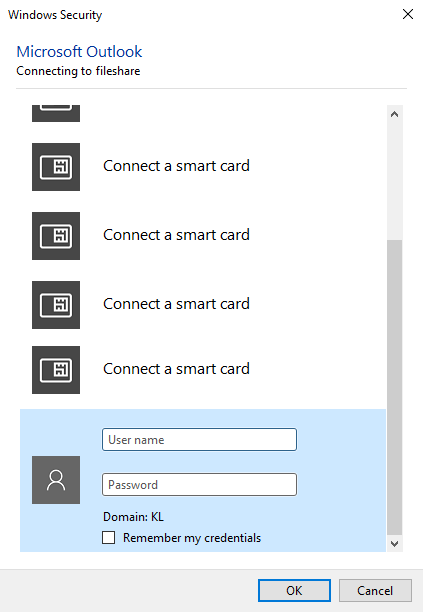

Responder scans the packets that flow through the emulated network and, upon seeing the username/password hash pairs, directs them to a fake HTTP/HTTPS/NTLM (it supports v1 and v2) server. The attack is triggered every time applications, including those running in the background, send authentication data, or when a user enters them in the standard dialogue windows in the web browser – for example, when user attempts to connect to a shared folder or printer.

Intercepting the hash in automatic mode, which is effective even if the system is locked, only works if the computer has another active local network connection.

As stated above, we tried this proof of concept in three scenarios:

- Against a corporate computer logged into a domain

- Against a corporate computer on a public network

- Against a home computer

In the first scenario we found that the device managed to intercept not only the packets from the system it’s connected to via USB but also NTLM authentication requests from other corporate network users in the domain. We mapped the number of intercepted hashes against the time elapsed, which is shown in the graph below:

Playing around with our “blackbox” for a few minutes, we got proof that the longer the device is connected, the more user hashes it extracts from the network. Extrapolating the “experimental” data, we can conclude that the number of hashes it can extract in our setting is around 50 hashes per hour. Of course, the real numbers depend on the network topology, namely, the amount of users within one segment, and their activity. We didn’t risk running the experiment for longer than half an hour because we also stumbled on some peculiar side effects, which we will describe in a few moments.

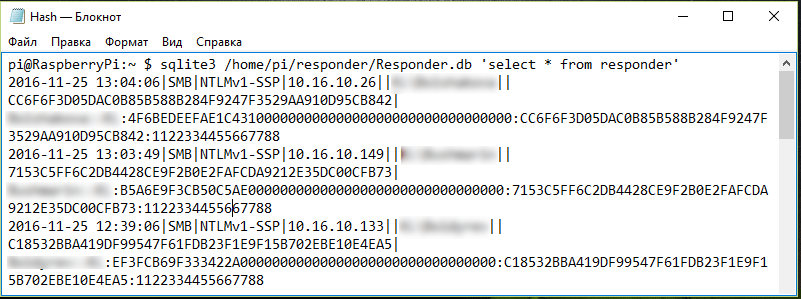

The extracted hashes are stored in a plain-text file:

In the second scenario we were only able to extract the connected system’s user credentials: domain/Windows name and password hash. We might have gotten more if we had set up shared network resources which users could try to access, but we’re going to leave that outside the scope of this research.

In the third scenario, we could only get the credentials of the owner of the system, which wasn’t connect to a domain authentication service. Again, we assume that setting up shared network resources and allowing other users to connect to them could lead to results similar to those we observed in the corporate network.

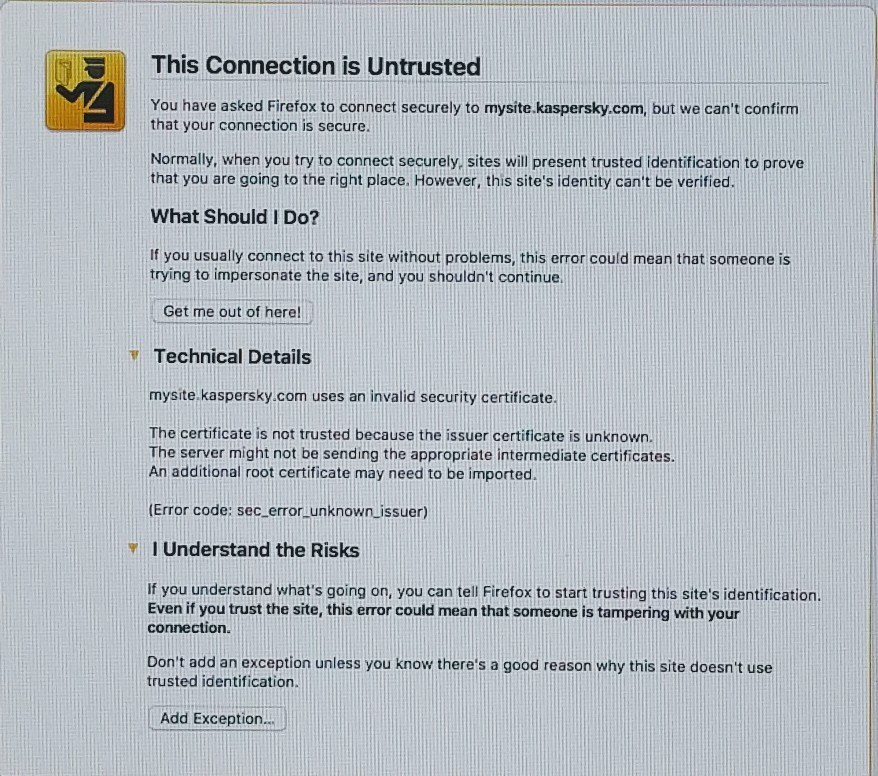

The described method of intercepting the hashes worked on Mac OS, too. When we tried to reach an intranet site which requires entering a domain name, we saw this dialogue warning that the security certificate is invalid.

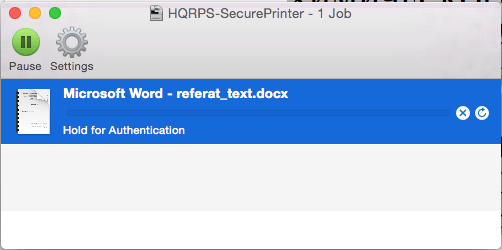

Now, the interesting side effect we mentioned above was that when the device was connected to a[ny] system in the network, tasks sent out to the network printer from other machines in the same network were put on hold in the printer queue. When the user attempted to enter the credentials in the authentication dialogue window, the queue didn’t clear. That’s because these credentials didn’t reach the network printer, landing in the Raspberry Pi’s flash memory instead. Similar behavior was observed when trying to connect to remote folders via the SMB protocol from a Mac system.

Bonus: Raspberry Pi Zero vs. Raspberry Pi 3

Once we saw that the NTLM systems of both Windows and Mac had come under attack from the microcomputer, we decided to try it against Linux. Furthermore, we decided to attack the Raspberry Pi itself, since Raspbian OS is built on the Debian Weezy core.

We reproduced the experiment, this time targeting Raspberry Pi 3 (by the way, connecting it to the corporate network was a challenging task in itself, but doable, so we won’t focus on it here). And here we had a pleasant surprise – Raspbian OS resisted assigning the higher priority to a USB device network, always choosing the built-in Ethernet as default. In this case, the Responder app was active, but could do nothing because packets didn’t flow through the device. When we manually removed the built-in Ethernet connection, the picture was similar to that we had observed previously with Windows.

Similar behavior was observed on the desktop version of Debian running on Chromebook – the system doesn’t automatically set the USB Ethernet adapter as default. Therefore, if we connect Raspberry Pi Zero to a system running Debian, the attack will fail. And we don’t think that creating Raspberry Pi-in-the-middle attacks is likely to take off, because they are much harder to implement and much easier to detect.

Experiment 2: stealing cookies

Methodology

While working on the first experiment, we heard claims that it’s possible to steal cookies from a PC when a Raspberry Pi Zero is connected to it via USB. We found an app called HackPi, a variant of PoisonTap (an XSS JavaScript) with Responder, which we described above.

The microcomputer in this experiment was configured just like in the previous one. HackPi works even better at establishing itself as a network adapter because it has an enhanced mechanism of desktop OS discovery: it is able to automatically install the network device driver on Windows 7/8/10, Mac and –nix operating systems. While in the first series of experiments, an attack could fail on Windows 7, 8 or Vista if the Remote NDIS Internet sharing device didn’t install itself automatically (especially when the PC is locked). And, unlike in the previous series, HackPi never had trouble assigning itself the default network adapter priority under Mac OS either.

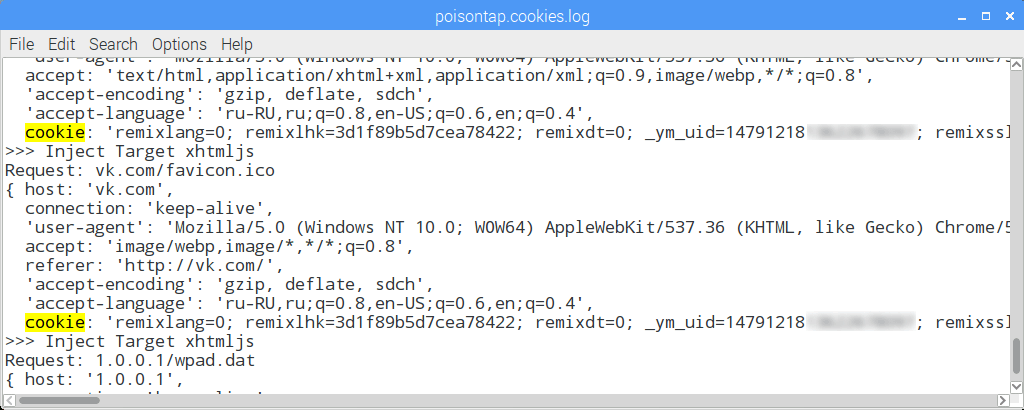

What differs from the first experiment is that the cookies are stolen using the malicious Java Script launched from the locally stored web page. If successful, PoisonTap’s script saves the cookies intercepted from sites, a list of which is also locally stored.

Results

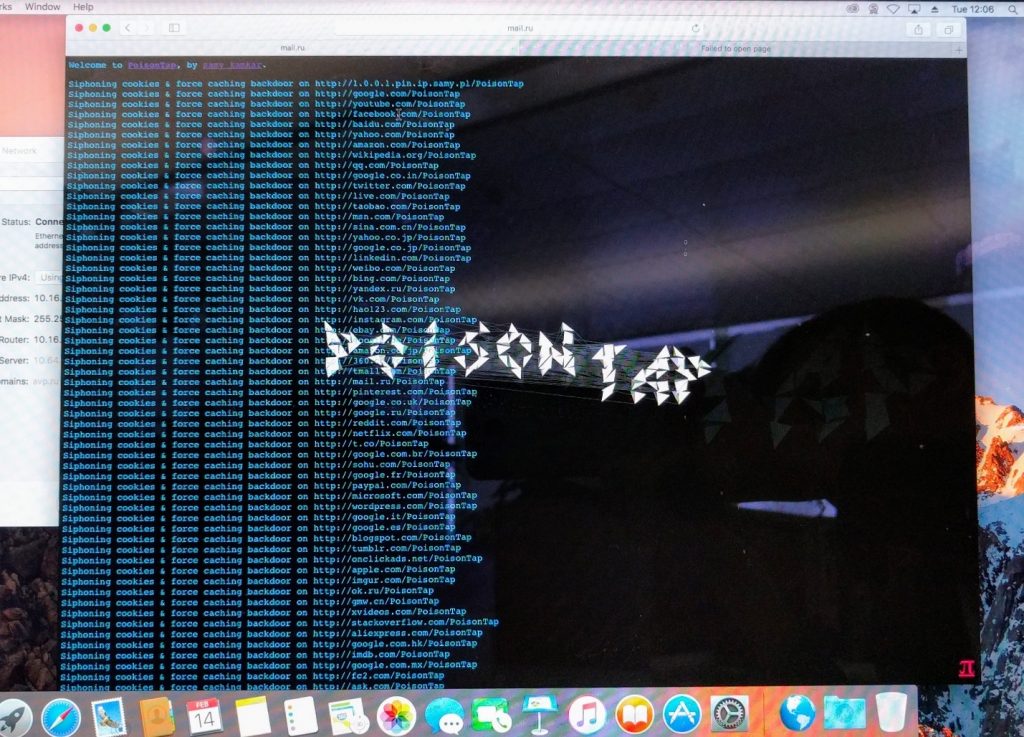

If the computer is not locked and the user opens the browser, Java Script initiates the redirecting of web requests to a malicious local web page. Then the browser opens the websites from the previously defined list. It is indeed quite spectacular:

If the user does nothing, Raspberry Pi Zero launches the default browser with URL go.microsoft.com in the address line after a short timeout. Then the process goes ahead as described. However, if the default browser has no cookies in the browser history, the attackers gain nothing.

Among the sites we’ve seen in the list supplied with the script were youtube.com, google.com, vk.com, facebook.com, twitter.com, yandex.ru, mail.ru and over 100 other web addresses. This is what the log of stolen cookies looks like:

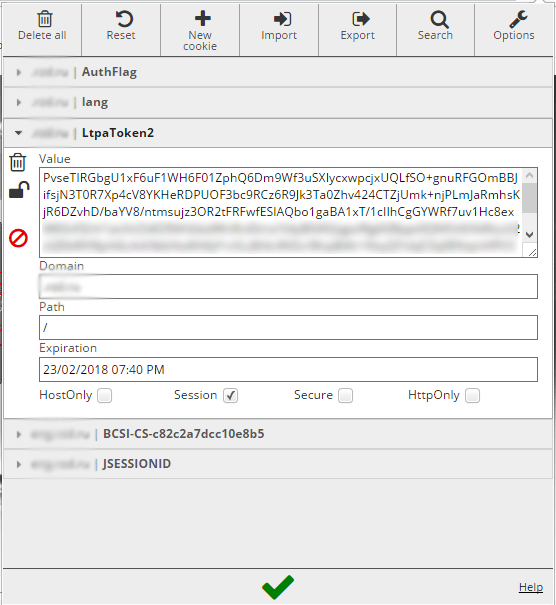

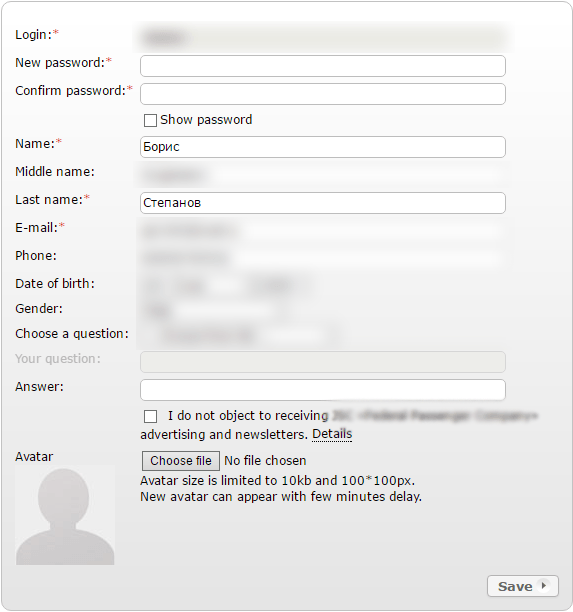

We checked the validity of stolen cookies using the pikabu.ru website as an example by pasting the info into a clean browser field on other machines and were able to get hold of the user’s account along with all the statistics. On another website belonging to a railroad company vending service, we were able to retrieve the user’s token and take over the user’s account on another computer, because authentication protocol used only one LtpaToken2 for session identification.

Now this is more serious, because in this case the criminals can get information about previous orders made by the victim, part of their passport number, name, date of birth, email and phone number.

One of the strong points of this attack is that enthusiasts have learned how to automatically install the network device driver on all systems found in today’s corporate environments: Windows 7/8/10, Mac OS X. However, this scenario doesn’t work against a locked system – at least, for now. But we don’t think you should become too complacent; we assume it’s only a matter of time before the enthusiasts overcome this as well. Especially given that the number of these enthusiasts is growing every day.

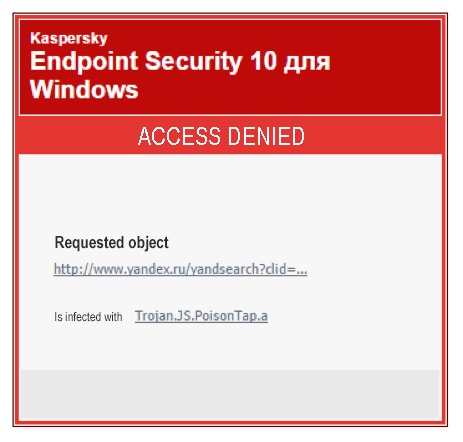

Also, the malicious web page is blocked by all Kaspersky Lab products, which detect it as Trojan.JS.Poisontap.a. We also assume that this malicious web page will be blocked by the products of all other major anti-malware vendors.

Conclusions

There is already a wide array of single-board microcomputers: from the cheap and universal Raspberry Pi Zero to computing sticks specifically tuned for penetration testing, which cannot be visually differentiated from USB flash drives. To answer the main question of just how serious this threat is, we can say that at the moment it is overrated. However, we don’t advise underestimating the capabilities of IoT enthusiasts and it’s better to assume that those obstacles which we discovered in our experiment, have already been overcome.

Right now we can say that Windows PCs are the systems most prone to attacks aimed at intercepting the authentication name and password with a USB-connected Raspberry Pi. The attack works even if the user doesn’t have local or system administrator privileges, and can retrieve the domain credentials of other users, including those with administrator privileges. And it works against Mac OS systems, too.

The second type of attack that steals cookies only works (so far) when the system is unlocked, which reduces the chances of success. It also redirects traffic to a malicious page, which is easily blocked by a security solution. And, of course, stolen cookies are only useful on those websites that don’t employ a strict HTTP transport policy.

Recommendations

However, there are a number of recommendations we’d like to give you to avoid becoming easy prey for attackers.

Users

1. Never leave your system unlocked, especially when you need to leave your computer for a moment and you are in a public place.

2. On returning to your computer, check to see if there are any extra USB devices sticking out of your ports. See a flash drive, or something that looks like a flash drive? If you didn’t stick it in, we suggest you remove it immediately.

3. Are you being asked to share something via external flash drive? Again, it’s better to make sure that it’s actually a flash drive. Even better – send the file via cloud or email.

4. Make a habit of ending sessions on sites that require authentication. Usually, this means clicking on a “Log out” button.

5. Change passwords regularly – both on your PC and the websites you use frequently. Remember that not all of your favorite websites may use mechanisms to protect against cookie data substitution. You can use specialized password management software for easy management of strong and secure passwords, such as the free Kaspersky Password Manager.

6. Enable two-factor authentication, for example, by requesting login confirmation or with a hardware token.

7. Of course, it’s strongly recommended to install and regularly update a security solution from a proven and trusted vendor.

Administrators

1. If the network topology allows it, we suggest using solely Kerberos protocol for authenticating domain users. If, however, there is a demand for supporting legacy systems with LLNMR and NTLM authentication, we recommend breaking down the network into segments, so that even if one segment is compromised, attackers cannot access the whole network.

2. Restrict privileged domain users from logging in to the legacy systems, especially domain administrators.

3. Domain user passwords should be changed regularly. If, for whatever reason, the organization’s policy does not involve regular password changes, please change the policy. Like, yesterday.

4. All of the computers within a corporate network have to be protected with security solutions and regular updates should be ensured.

5. In order to prevent the connection of unauthorized USB devices, it can be useful to activate a Device Control feature, available in the Kaspersky Endpoint Security for Business suite.

6. If you own the web resource, we recommend activating the HSTS (HTTP strict transport security) which prevents switching from HTTPS to HTTP protocol and spoofing the credentials from a stolen cookie.

7. If possible, disable the listening mode and activate the Client (AP) isolation setting in Wi-Fi routers and switches, disabling them from listening to other workstations’ traffic.

8. Activate the DHCP Snooping setting to protect corporate network users from capturing their DHCP requests by fake DHCP servers.

Last, but not least, you never know if your credentials have been leaked from a site you’ve been to before – online or physical. Thus, we strongly recommend that you check your credentials on the HaveIbeenPwned website to be sure.

50 hashes per hour

Scott S

“If, for whatever reason, the organization’s policy does not involve regular password changes, please change the policy. Like, yesterday.”

I think you need to change your advice, like yesterday, or last year when the recommendations came out.

https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2016/08/frequent_passwo.html

http://www.csoonline.com/article/3113710/data-protection/regular-password-changes-make-things-worse.html

Very interesting article though. Thanks