When the computer industry was just starting to evolve, no one could have guessed that relatively soon there would be a computer in every home. Today, many of us entrust our finances, personal correspondence, and much more to these machines.

Later, a skyrocketing number of users brought business to the Internet, leading to a rapid increase in network services. It would seem that Internet users were enjoying everything they could have wished for. But the arrival of cyber criminals, constantly searching for any and all opportunities to swindle unsuspecting users, changed everything.

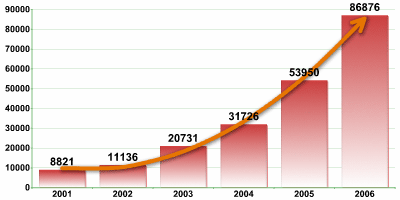

Cybercrime has become an integral part of the Internet, and the market for malware is expanding rapidly. Previously unknown malicious programs are multiplying at an exponential rate, as Figure 1 illustrates.

Fig. 1: Increase in the number of new malicious programs.

Source: Kaspersky Lab

Previously, when malicious programs were written by students in their free time, antivirus companies were able to effortlessly repel their attacks, but this has become increasingly difficult with every passing year. In the near future, IT security companies will probably be able to continue combating to some extent the ever-increasing amount of malicious programs, spam and other manifestations of cybercrime. However, the question now is not whether cybercrime can be eliminated, but the extent to which its evolution can be hindered.

The stumbling block in this bitter struggle is the user, the source of income for criminals. According to estimates from various organizations, cybercrime-related revenue now significantly exceeds the income of the antivirus industry. The battle is in full swing.

This article examines the current situation – what today’s cyber criminals are doing to thwart the efforts of IT security companies, and who may be able to affect the development of cybercrime in the foreseeable future.

Cyber criminals vs. IT security companies

IT security companies are currently the main – and practically the only – force capable of taking successful action against cybercrime. Malicious users are constantly inventing new and improved ways to get around today’s technology, which drives the IT security industry to develop new means of protection. The conflict between the security industry and cyber criminals has evolved in an unusual way; cyber criminals don’t always rush to be the first to take on new security technologies, each of which first undergoes scrupulous “durability” testing.

This was clearly demonstrated by Blue Security and its Blue Frog project, which was initially positioned as a successful antispam solution. At first, everything worked well – some Blue Frog users saw a 25% decline in the volume of unwanted correspondence they received. A year later, the project was causing huge problems for spammers, which ultimately led to its demise: Blue Frog was closed down after a series of powerful DDoS attacks.

It’s not a bed of roses in the antivirus industry, either. Cyber criminal activity comes in different forms, from a stream of relatively insignificant threats, which can be easily combated, to full-scale, multi-partite attacks on antivirus solutions.

Examples of threats caused by smaller attacks include the following:

- The authors of the Bagle worm tracked antivirus companies’ attempts to access a malicious website used by the worm and placed an absolutely clean file on this site. This meant that antivirus companies would not be able to obtain or analyze the authors’ malicious “creation”, and, consequently, would not be able to add it to antivirus databases. But when regular users opened the link, malicious code would be downloaded to the victim machine.

- The authors of Trojan-PSW.Win32.LdPinch continually track firewall activity. When the firewall displays a warning asking whether or not an application activity linked to the Trojan is permitted, the Trojan itself will ‘click’ on yes.

- Cyber criminals or other malicious users mass mail malicious programs disguised as updates from antivirus companies on a regular basis. This is done in order to discredit the companies concerned.

There has been nothing really new in terms of multi-partite approaches used to combat antivirus solutions. The methods currently used can be divided into two categories:

- passive resistance;

- active resistance.

Passive resistance

Passive resistance employs methods that make it difficult to analyze and/or detect malicious content. There are many approaches that can be applied for these purposes (dynamic code generators, polymorphism, etc.), but in most cases, the authors of malicious programs don’t spend much time or effort on developing these types of mechanisms. They use a much simpler solution in order to achieve their goals: so-called packers. These are utilities that use dedicated algorithms to encode the target executable program while retaining its functionality. The use of packers makes a malicious user’s task much easier: in order to prevent an antivirus program from detecting an already known malicious program, the author no longer has to rewrite it from scratch – all he has to do is re-pack it with a packer that is not known to the antivirus program. The result is the same, and the costs are much lower.

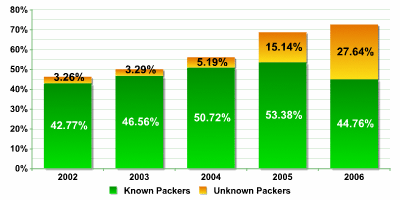

As described above, most executable malicious files are packed in this manner. Figure 2, below, shows the number of packed malicious programs compared to the number of new malicious programs.

Fig. 2: Increase in the amount of packed samples

(less than 1% error margin in identifying samples packed by unknown packers).

Source: Kaspersky Lab

The continued increase in the number of packed samples in the overall number of new, previously unknown malicious programs demonstrates that malicious users are confident that using packers is effective.

Clearly, it doesn’t make much sense to use packers that antivirus programs can already detect – the original malicious code will, as a result, still be caught by the antivirus product. This is why more and more often, cyber criminals are now using packers that are not known to the antivirus industry; these are circulated as ‘off-the-shelf’ packers, modified or reworked by the authors themselves. The increase in the number of new malicious programs packed using packers that are not recognized by Kaspersky Anti-Virus are shown in figure 2.

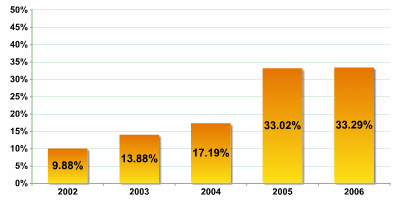

Recently, we have seen more and more so-called “sandwiches”. This is where one malicious program is packed using several packers at once in hopes that antivirus programs will not be able to detect at least one of the packers. The increase in the use of “sandwiches” in relation to the number of new packed malicious programs is shown in figure

Fig. 3: Increase in the number of “sandwiches” in the total number of new packed samples.

Source: Kaspersky Lab

Virtual machines and emulators are very efficient at analyzing packed malicious code. Having understood this, virus writers have responded by creating more malicious programs which use code that combats antivirus technologies. In turn, antivirus companies responded with more refined technologies, leading to yet another turn of the screw…

Active resistance

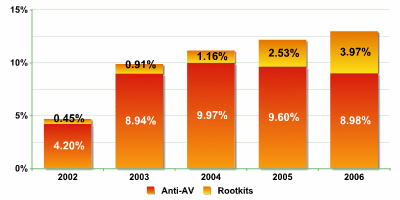

Fig. 4: Increase in the number of new modifications of malicious programs that actively combat security solutions.

Source: Kaspersky Lab

The continued acceleration of the increase in new malicious programs (fig.1) is now accompanied by an increase in the total number of malicious programs which actively combat antivirus solutions. First and foremost, this involves virus writers using rootkit technologies in order to increase the lifespan of a virus in the infected system: if a malicious program has stealth capabilities, then it is less likely to end up in an antivirus company’s database.

Previously, virus writers targeted a handful of antivirus solutions. These days it’s easy to find malicious programs which destroy dozens – if not hundreds – of security solutions.

Despite the efforts of cyber criminals, antivirus companies are relatively quick to develop and implement security mechanisms which have already slowed the increase in the number of malicious programs which combat antivirus solutions. In addition to this, they have also implemented anti-rootkit technologies.

Cyber criminals have responded with malicious programs with built-in drivers: kernel mode code which has rights enabling it to control the system, rather than standard code, is used to eliminate the antivirus solution. One example of this type of malicious program is Email-Worm.Win32.Bagle.gr.

Cyber criminals are also attacking on other fronts. For example, the authors of the Warezov worm are releasing modifications to their worm faster and faster in order to make the lives of antivirus companies more difficult.

The window of opportunity between an exploit appearing after the corresponding patch for a vulnerability is released is also on the decline, and cyber criminals are well aware of this. Malicious programs are constantly evolving and moving to new environments.

In terms of the successes of the antivirus industry, one example is the decreased interest shown by virus writers in email traffic. Today’s cyber criminals now find it ineffective to spread their malicious programs via email, even though this used to be a popular method. The difference is that today, malicious code can be quickly detected and blocked even before a mass mailing has been completed. Nevertheless, malicious users have no intention of giving up and they have already increased their use of websites to spread malicious programs.

Cyber crime is putting relentless, increased pressure on IT security companies. Increased illegal revenue allows cyber criminals to hire highly qualified accomplices and develop new attack technologies. Over the next several years, IT security companies will be able to use all their resources to reduce the pressure exerted by malicious users, but it will become ever more difficult. Only time can tell what will happen next.

Cyber criminals vs. other companies

Companies which only yesterday had been victims, and exhausted by the endless attacks both on their own infrastructures and those of their clients, have now begun to show teeth. One could say that 2004 and 2005 were the years during which the Internet became fully criminalized and during which the number of new viruses skyrocketed. But 2006 was the year when business began to acknowledge the problem presented by cyber crime.

One example is the financial organizations that independently began to take measures to frustrate cyber criminals. Last year, banks everywhere introduced various methods aimed at making registration more secure, ranging from one-time passwords to biometric authentification. This made it much more difficult for malicious users to develop new viruses targeting the financial sector.

More and more frequently software solutions provide online notification about new patches, but unfortunately, malicious users respond much faster to these notifications than do regular users. Developers’ response time to new patch releases is also gradually getting shorter.

Cyber criminals vs. the government

Governments possess the most extensive and powerful means to fighting cybercrime, but they are also one of the slowest-moving participants in the battle against cybercrime. The time when the situation could have been brought under control is long past.

Crime on the Internet has become so widespread that the authorities simply don’t have sufficient resources to tackle a significant number of all crimes committed. It is extremely difficult for law enforcement bodies to work under conditions in which criminal acts are not limited by nation-state borders (malicious users can maintain a server in one country, attack users in another, and actually be physically located in a third country). Moreover, the infrastructure of the Internet allows cyber criminals to act at lightning-fast speed while maintaining anonymity.

Furthermore, the government system moves very slowly. A great deal of valuable time is spent on the decision-making process and reaching agreement at different levels. By the time a government agency gets around to investigating cyber criminals, they will have already moved on from their initial physical location and will have changed the hosting service they use more than once.

These days, government structures are similar to the victims of cybercrime, rather than those combating cyber criminals. There are a number of examples which uphold this claim, all of which were given wide coverage in the media:

- Almost every major international political conflict spills over onto the Internet, becoming a conflict between cyber criminals in the conflicting countries, which can later be seen in the hacking of government websites. This happened in late 2005, when political debates about the ownership of fishing territories led to a conflict between malicious users in Peru and Chile. This same phenomenon was also seen in the Lebanon-Israel conflict, during which dozens of Israeli, Lebanese and American websites were attacked on a weekly basis. The standoff between cyber vandals in Japan and China and the US and China have been going on for some time now. Nearly all defacements of government websites which result from squabbles regarding international relations remain unpunished.

- When malicious users are unhappy with the actions of one government or another, we often see DDoS attacks against that country, or other types of malicious action. This happened to Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in autumn 2006, when a DDoS attack was carried out on the Ministry’s site, as a protest against an official visit to a “militant” temple. This also happened to Swedish government websites in early summer 2006 as a protest against the country’s anti-piracy measures.

- Government structures are often viewed as a source of exclusive information that can be sold for good money on the black market or used in attacks. One excellent example is that of RusFinMonitoring (the Russian Financial Monitoring Service), which registers one-time transactions exceeding $20,000. According to the deputy head of the agency, hackers try to gain access to its computer system on a daily basis in order to get their hands on new information about bank clients.

Having acknowledged the scale and serious nature of cybercrime, the authorities are trying to address the problem. Although government agencies have not been quick off the mark, they have begun to take the following steps:

- In order to facilitate interaction and accelerate response time, the law enforcement agencies of various countries are making attempts to create a cyber-Interpol;

- In summer 2006 at the regional ASEAN Forum, a decision was made to create a common network for reporting computer-related crimes and to apply recommendations on counteracting cybercrime and other relevant information;

- In summer 2006, the US Senate ratified the decision to join the European agreement on the fight against cybercrime, which has already been signed by several dozen countries;

- A number of countries are discussing proposals to make current legislation stricter (Russia, Great Britain, and others).

According to government officials, the measures that have been taken so far are making a big difference in the fight against cybercrime and terrorism and will enable law enforcement officials to solve cybercrimes more quickly. Of course, it will take time for this to happen; currently, cyber criminals barely notice that anyone at government level is trying to thwart their efforts. This reaction – or lack thereof – more or less stems from the fact that malicious users are completely ignoring government efforts. The measures that have been taken so far haven’t so much as scratched the surface. There is one positive point here, however, which is that the government machine has finally ground into action, and it is moving in the right direction.

Conclusion

Today, only IT security companies are capable of combating cybercrime. But the situation is deteriorating, and at an ever increasing rate. Every year it’s becoming harder and harder to ensure security.

Cybercrime is becoming increasingly more organized and more consolidated. Unfortunately, from our point of view, co-operation is not yet widespread enough. Antivirus companies, the government and other companies are not very keen on sharing information with one another, which often leads to valuable time being lost, hindering the investigation of cybercrimes and the introduction or enforcement of appropriate measures.

There’s no doubt that it’s still possible to remedy the situation, but this will require a concerted effort. In addition to developing and launching new security technologies, a united front, with the active participation of all those involved in the fight against cybercrime, is the only thing that will make a real difference.

The Virtual Conflict – Who Will Triumph?