In the first part of our analysis we looked at the distribution and infection mechanisms used by the Flashfake (a.k.a. Flashback) malicious program, which by the end of April 2012 had infected over 748,000 Mac OS X computers. In this second part we’ll look at its other functions and how the cybercriminals behind Flashfake are cashing in on the botnet they have created.

Dynamic library

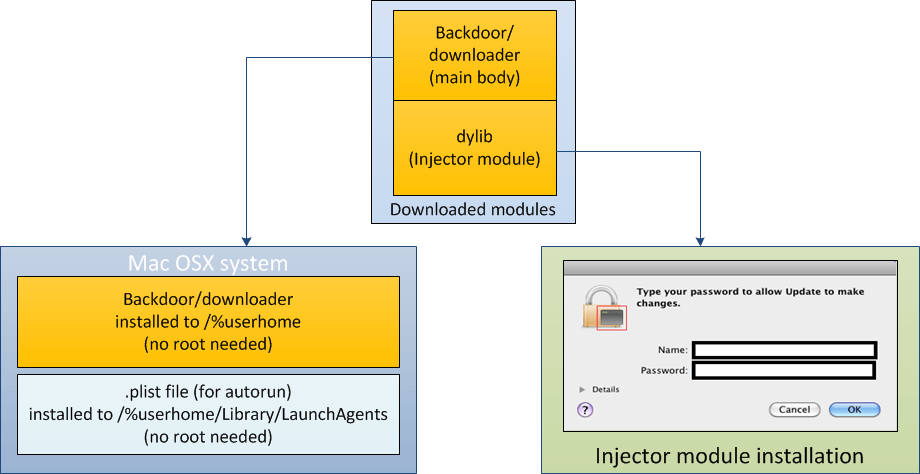

The Flashfake malicious program is made up of multiple modules as well as a dynamic library that is injected into browser processes. This dynamic library is implemented as an injector module for malicious code – see the diagram below.

Flashfake operational flowchart

Our signature database currently includes two modifications of this library, more commonly known as libmbot.dylib. This dynamic library is a standard Mach-O pack for 32-bit and 64-bit systems and is approximately 400 KB in size.

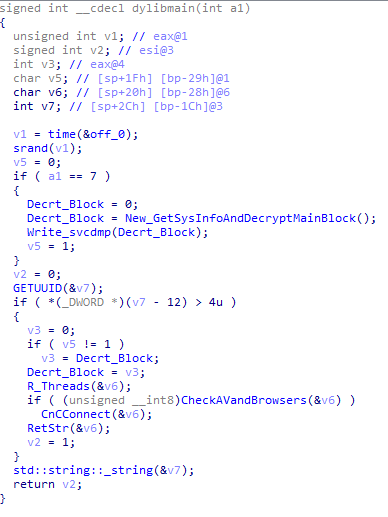

The library’s operation starts with the standard _dylibmain function, which accepts an integer as its input. By default, for the payload to be activated, the integer should have the value 7.

Pseudocode to launch the dynamic library’s initial functionality

After checking the input parameter, the library starts decrypting the configuration block defining all the malicious payload of the library. Decryption is performed using the RC4 algorithm with base64 decoding. The configuration block is a table with each entry consisting of an ID, entry type and the entry’s value. All subsequent activity by the library derives from the relevant instruction for the entry ID in this block.

Sample of the configuration block for the malicious Flashfake dynamic library

This block contains the following types of entries, which define functionality:

- function for updating and infecting browsers via DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIES (described in Part 1 of our analysis);

- initial list of domains acting as C&C servers for the dynamic library;

- function for generating domain names in the ‘org’, ‘com’, ‘co.uk’, ‘cn’, and ‘in’ zones to search for C&C servers;

- function for generating third-level domains for the domains ‘.PassingGas.net’, ‘.MyRedirect.us’, ‘.rr.nu’, ‘.Kwik.To’, ‘.myfw.us’, ‘.OnTheWeb.nu’ etc.;

- a function for searching for C&C servers by generating search requests for the mobile version of Twitter;

- function for injecting external code into the context of sites visited by the user.

Injection mechanism

By default the library, once located in the browser execution context, tracks all the user’s requests by hooking the send, recv, CFReadStreamRead and CFWriteStreamWrite functions. When it detects that a site mentioned in the configuration block is accessed, the library injects the following JavaScript from the server into the browser context.

JavaScript injected into a browser execution context

The value of the {DOMAIN} field is taken from the list of initial C&C servers, e.g.:

googlesindication.com, gotredirect.com, dotheredirect.com, adfreefeed.com, googlesindications.cn, googlesindications.in, instasearchmod.com, jsseachupdates.cn.

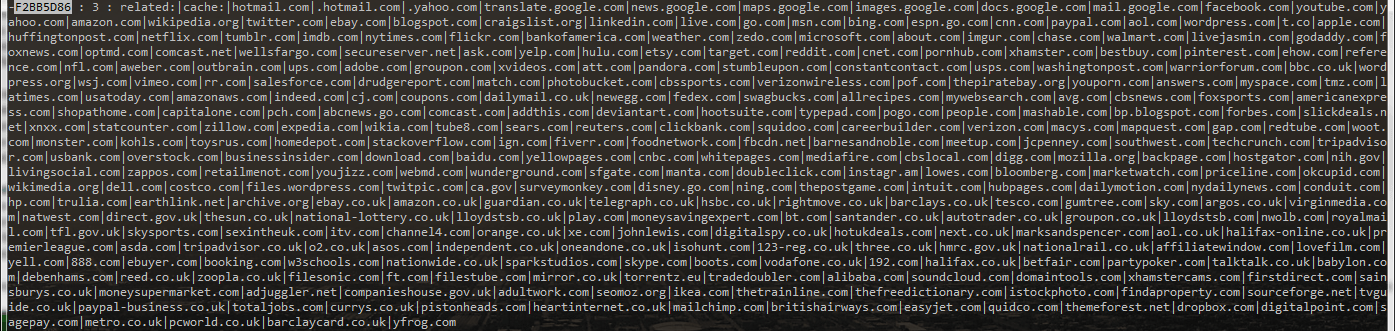

By default, this JavaScript is always executed whenever the browser accesses google.com. However, the configuration block contains a list of 321 domains for which the JavaScript is not permitted to execute when they are mentioned in search requests. As well as search engines, the list includes social networks, news sites, and online stores and banks. These domains are most probably on the list in order to minimize traffic to the cybercriminals’ server.

The list of domains that are excluded from the JavaScript injection

Version audit

The dynamic library’s functionality includes a self-updating mechanism. The creators have also included a mechanism that verifies C&C servers and update signatures using an RSA algorithm. At present there are two main versions of the malicious library. Unfortunately, the linking date for all the malicious files is set as 1 January 1970, which prevents us from creating an exact timeline for the release of the libraries. Nevertheless, differences in the functions included in the libraries may allow us to establish when they appeared.

Based on our analysis, the characteristic features of version 1.0 (MD50x8ACFEBD614C5A9D4FBC65EDDB1444C58), which was active until March 2012, are random library names, hooking of the CFReadStreamRead and CFWriteStreamWrite functions, and installation in /Users/Shared/.svcdmp. The malicious JavaScript is also included in the body of the actual malicious program. The only differences in version 1.1 are changes to the initial list of C&C servers, and the algorithm for generating their new domain names.

In version 2.0 (MD5 434C675B67AB088C87C27C7B0BC8ECC2) – active in March 2012 – a C&C server search algorithm that functions via Twitter.com was added. The malicious JavaScript was moved to the configuration block, and support was added to the send and recv functions for traffic interception and spoofing. A fixed name for the malicious library – libmbot.dylib – was also added in version 2.0, as well as additional loaders and an additional check of the input parameter for activating the main part of the malicious program. Version 2.1 includes a new algorithm for searching for C&C servers via Twitter. The latest version of the library that we currently know of – version 2.2 – is of interest primarily due to its Firefox browser add-on.

Firefox add-on

In this version of the dynamic library all the machinations with user search requests in Google are by default carried out by hooking the send, recv, CFReadStreamRead, and CFWriteStreamWrite functions. This is a universal approach for all browsers on Mac OS X, but it requires extra effort when crafting code to decode user traffic. It therefore looks like an add-on for Firefox named AdobeFlashPlayer 11.1 has appeared in the configuration block in order to minimize the modifications to version 2.2.

The malicious add-on for Firefox disguised as an Adobe Flash Player add-on

Genuine Adobe Flash add-on

This malicious add-on has the same functionality, i.e., intercepting user data from Google and substituting traffic using data from C&C servers.

Conclusion

Flashfake is currently the most widespread malicious program for Mac OS X computers. This fact is down to Apple’s negligence when it comes to updating its operating system as well as the ability of cybercriminals to bring all the latest malware technology into play: zero-day vulnerabilities, checking for the presence of antivirus solutions on a system, self-protection measures, cryptographically strong algorithms for communicating with C&C servers, making use of publically available services to manage botnets. And all these technologies are capable of targeting both Mac and Windows systems. By interfering with user activity on Google, the Flashfake authors have created a steady source of income that is capable of generating thousands of dollars per day. It remains unclear which partner program is providing links for the fake search results and who exactly is helping the cybercriminals to spread the program.

That means we’ll be back with more on this topic…

The anatomy of Flashfake. Part 2