Turla, also known as Venomous Bear, Waterbug, and Uroboros, may be best known for what was at the time an “ultra complex” snake rootkit focused on NATO-related targets, but their malware set and activity is much broader. Our current focus is on more recent and upcoming activity from this APT, which brings an interesting mix of old code, new code, and new speculations as to where they will strike next and what they will shed.

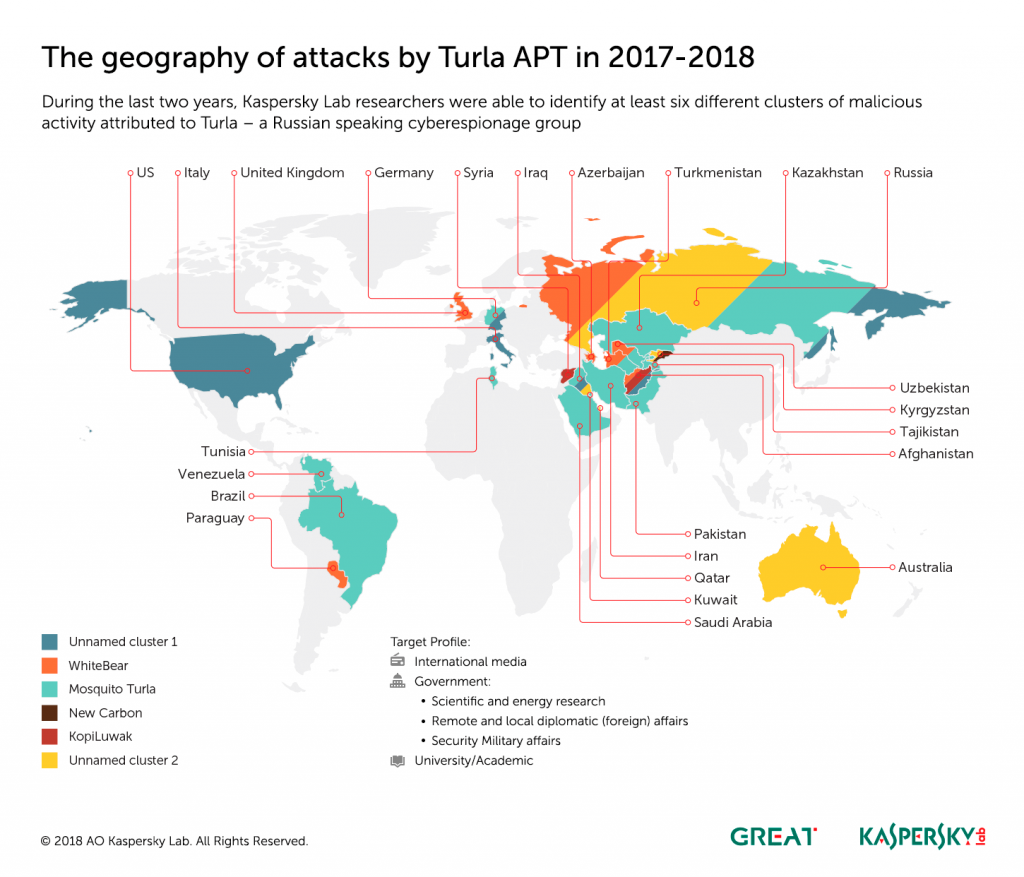

Much of our 2018 research focused on Turla’s KopiLuwak javascript backdoor, new variants of the Carbon framework and meterpreter delivery techniques. Also interesting was Mosquito’s changing delivery techniques, customized PoshSec-Mod open-source powershell use, and borrowed injector code. We tied some of this activity together with infrastructure and data points from WhiteBear and Mosquito infrastructure and activity in 2017 and 2018.

For a first, our KopiLuwak research identified targets and delivery techniques, bringing more accuracy and reliability to the discussion. Also interesting is a review of Turla scripting artefacts leading to newer efforts like KopiLuwak, tracing from older scripting in development efforts in WhiteAtlas and WhiteBear. And, we find 2018 KopiLuwak delivery techniques that unexpectedly matched Zebrocy spearphishing techniques for a first time as well.

Also highly interesting and unusual was the MiTM techniques delivering Mosquito backdoors. In all likelihood, Turla delivered a physical presence of some sort within Wifi range of targets. Download sessions with Adobe’s website were intercepted and injected to deliver Mosquito trojanized installers. This sort of hypothesis is supported by Mosquito installers’ consistent wifi credential theft. Meanwhile, injection and delivery techniques are undergoing changes in 2018 with reflective loaders and code enhancements. We expect to see more Mosquito activity into 2019.

And finally, we discuss the Carbon framework, tying together the older, elegant, and functional codebase sometimes called “Snake lite” with ongoing efforts to selectively monitor high value targets. It appears that the backdoor is pushed with meterpreter now. And, as we see code modifications and deployment in 2018, we predict more development work on this matured codebase along with selective deployment to continue into 2019.

Essentially, we are discussing ongoing activity revolving around several malware families:

- KopiLuwak and IcedCoffeer

- Carbon

- Mosquito

- WhiteBear

Technical Rattle

Turla’s Shifting to Scripting

KopiLuwak and IcedCoffee, WhiteBear, and WhiteAtlas

Since at least 2015 Turla has leveraged Javascript, powershell, and wsh in a number of ways, including in their malware dropper/installation operations as well as for implementing complete backdoors. The White Atlas framework often utilized a small Javascript script to execute the malware dropper payload after it was decrypted by the VBA macro code, then to delete the dropper afterwards. A much more advanced and highly obfuscated Javascript script was utilized in White Atlas samples that dropped a Firefox extension backdoor developed by Turla, but again the script was responsible for the simple tasks of writing out the extension.json configuration file for the extension and deleting itself for cleanup purposes.

IcedCoffee

Turla’s first foray into full-fledged Javascript backdoors began with the usage of the IcedCoffee backdoor that we reported on in our private June 2016 “Ice Turla” report (available to customers of Kaspersky APT Intelligence Services), which led later to their more fully functional and complex, recently deployed, KopiLuwak backdoor. IcedCoffee was initially dropped by exploit-laden RTF documents, then later by macro-enabled Office documents. The macro code used to drop IcedCoffee was a slightly modified version of that found in White Atlas, which is consistent with the code sharing present in many Turla tools. A noteworthy change to the macro code was the addition of a simple web beacon that relayed basic information to Turla controlled servers upon execution of the macro, which not only helped profile the victim but also could be used to track the effectiveness of the attack.

IcedCoffee is a fairly basic backdoor which uses WMI to collect a variety of system and user information from the system, which is then encoded with base64, encrypted with RC4 and submitted via HTTP POST to the C2 server. IcedCoffee has no built-in command capability, instead it may receive javascript files from the C2 server, which are deobfuscated and executed in memory, leaving nothing behind on disk for forensic analysis. IcedCoffee was not widely deployed, rather it was targeted at diplomats, including Ambassadors, of European governments.

KopiLuwak

In November 2016, Kaspersky Lab observed a new round of weaponized macro documents that dropped a new, heavily obfuscated Javascript payload that we named KopiLuwak (one of the rarest and most expensive types of coffee in the world). The targeting for this new malware was consistent with earlier Turla operations, focusing on European governments, but it was even more selectively deployed than IcedCoffee.

The KopiLuwak script is decoded by macro code very similar to that previously seen with IcedCoffee, but the resulting script is not the final step. This script is executed with a parameter used as a key to RC4 decrypt an additional layer of javascript that contains the system information collection and command and control beaconing functionality. KopiLuwak performs a more comprehensive system and network reconnaissance collection, and like IcedCoffee leaves very little on disk for investigators to discover other than the base script.

Unlike IcedCoffee, KopiLuwak contains a basic set of command functionality, including the ability to run arbitrary system commands and uninstall itself. In mid-2017 a new version was discovered in which this command set had been further enhanced to include file download and data exfiltration capabilities.

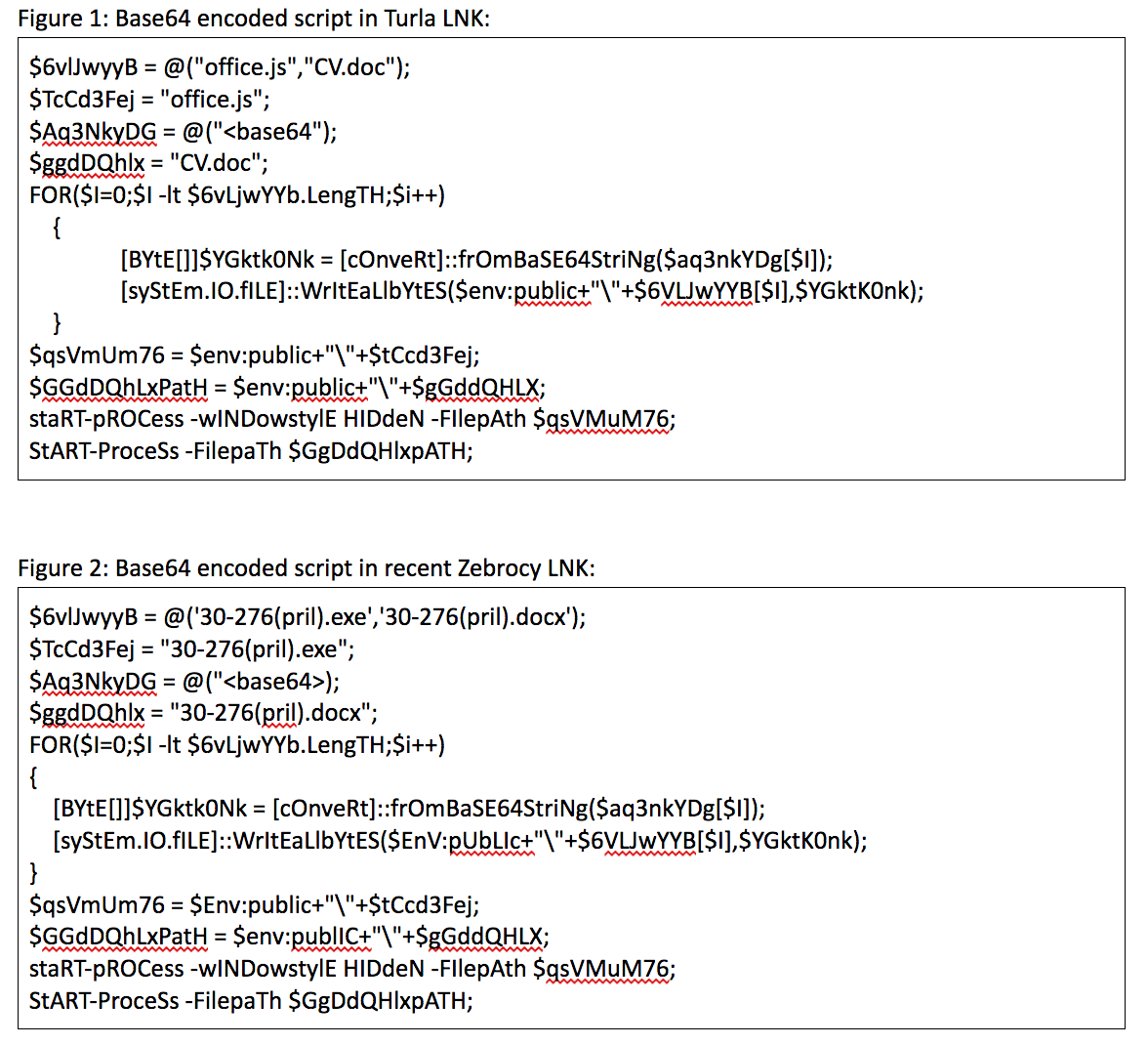

The most recent evolution in the KopiLuwak life cycle was observed in mid-2018 when we observed a very small set of systems in Syria and Afghanistan being targeted with a new delivery vector. In this campaign the KopiLuwak backdoor was encoded and delivered in a

Windows shortcut (.lnk) file. The lnk files were an especially interesting development because the powershell code they contain for decoding and dropping the payload is nearly identical to that utilized by the Zebrocy threat actor a month earlier.

Carbon – the long tail

Carbon continues to be deployed against government and foreign affairs related organizations in Central Asia. Carbon targeting in this region has shifted across a few countries since 2014. Here, we find a new orchestrator v3.8.2 and a new injected transport library v4.0.8 deployed to multiple systems. And while we cannot identify a concrete delivery event for the dropper, its appearance coincides with the presence of meterpreter. This meterpreter reliance also coincides with wider Turla use of open source tools that we documented towards the end of 2017 and beginning of 2018.

The Epic Turla operation reported in 2014 involved highly selective Carbon delivery and was a long term global operation that affected hundreds of victims. Only a small portion of these systems were upgraded to a malware set known as “the Carbon framework”, and even fewer received the Snake rootkit for “extreme persistence”. So, Carbon is known to be a sophisticated codebase with a long history and very selective delivery, and coincides with Snake rootkit development and deployment. In light of its age, it’s interesting that this codebase is currently being modified, with additional variants deployed to targets in 2018.

We expect Carbon framework code modifications and predict selective deployment of this matured codebase to continue into 2019 within Central Asia and related remote locations. A complex module like this one must require some effort and investment, and while corresponding loader/injector and lateral movement malware moves to open source, this backdoor package and its infrastructure is likely not going to be replaced altogether in the short term.

.JS attachments deliver Skipper/WhiteAtlas and WhiteBear

We introduced WhiteBear actionable data to our private customers early 2017, and similar analysis to that report was publicly shared eight months later. Again, it was a cluster of activity that continued to grow past expectations. It is interesting because WhiteBear shared known compromised infrastructure with KopiLuwak: soligro[.]com. WhiteBear scripted spearphish attachments also follows up on initial WhiteAtlas scripting development and deployment efforts.

Mosquito’s Changing 2018 Delivery Techniques

In March 2018, our private report customers received actionable data on Mosquito’s inclusion of fileless and customized Posh-SecMod metasploit components. When discussion of the group’s metasploit use was made public, their tactics began to change.

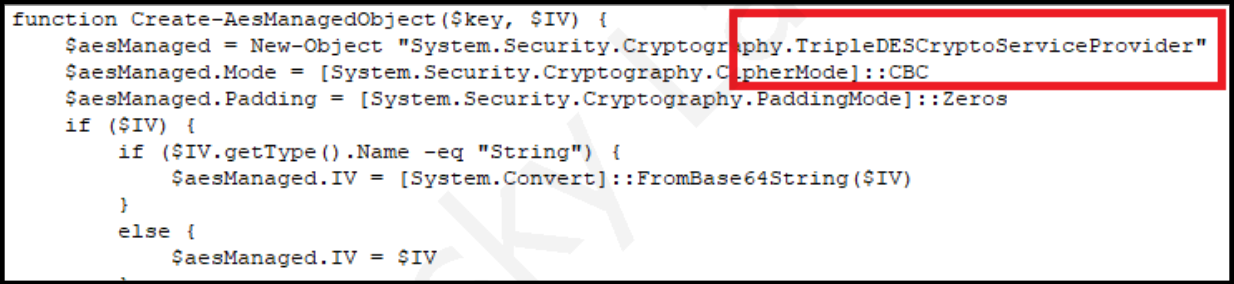

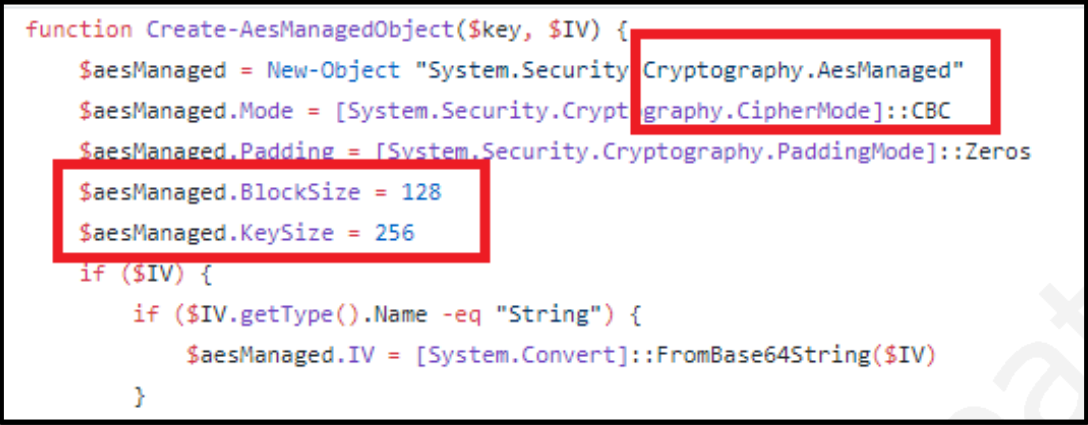

The “DllForUserFileLessInstaller” injector module maintained a compilation date of November 22, 2017, and was starting to be used by Mosquito to inject ComRAT modules into memory around January 2018. It is a small piece of metasploit injector code that accounts for issues with Wow64. Also, related open source powershell registry loader code oddly was modified to avoid AES use, and opt for 3DES encryption instead. Here is the modified Mosquito code:

And here is the default Posh-SecMod code that they ripped from:

We expect to see more open-source based or inspired fileless components and memory loaders from Mosquito throughout 2018. Perhaps this malware enhancement indicates that they are more interested in maintaining current access to victim organizations than developing offensive technologies.

MiTM and Ducking the Mosquito Net

We delivered actionable data on Mosquito to our private intel customers in early 2017. Our initial findings included data around an unusual and legitimate download URL for trojanized installers:

hxxp://admdownload.adobe[.]com/bin/live/flashplayer23ax_ra_install.exe

While we could not identify the MiTM techniques with accuracy at the time, it is possible either WiFi MiTM or router compromise was used in relation to these incidents. It is unlikely, but possible, that ISP-level FinFisher MiTM was used, considering multiple remote locations across the globe were targeted.

But there is more incident data that should be elaborated on. In some cases, two “.js” files were written to disk and the infected system configured to run them at startup. Their naming provides insight into the intention of this functionality, which is to keep the malware remotely updated via google application, and maintain local settings updates by loading and running “1.txt” at every startup. In a way, this staged script loading technique seems to be shared with the IcedCoffee javascript loading techniques observed in past Turla incidents focused on European government organizations. Updates are provided from the server-side, leading to fewer malware set findings.

- google_update_checker.js

- local_update_checker.js

So, we should consider the wifi data collection that Mosquito Turla performed during these updates, as it hasn’t been documented publicly. One of the first steps that several Mosquito installer packages performed after writing and running this local_update js file was to export all local host’s WiFi profiles (settings and passwords) to %APPDATA%\<profile>.xml with a command line call:

cmd.exe /c netsh wlan export profile key=clear folder="%APPDATA%"

They then gather more network information with a call to ipconfig and arp -a. Maintaining ongoing host-based collection of wifi credentials for target networks makes it far easier to possess ongoing access to wifi networks for spoofing and MiTM, as brute-forcing or otherwise cracking weakly secured WiFi networks becomes unnecessary. Perhaps this particular method of location-dependent intrusion and access is on the decline for Mosquito Turla, as we haven’t identified new URLs delivering trojanized code.

The Next Strike

It’s very interesting to see ongoing targeting overlap, or the lack of overlap, with other APT activity. Noting that Turla was absent from the milestone DNC hack event where Sofacy and CozyDuke were both present, but Turla was quietly active around the globe on other projects, provides some insight as to ongoing motivations and ambitions of this group. It is interesting that data related to these organizations has not been weaponized and found online while this Turla activity quietly carries on.

Both Turla’s Mosquito and Carbon projects focus mainly on diplomatic and foreign affairs targets. While WhiteAtlas and WhiteBear activity stretched across the globe to include foreign affairs related organizations, not all targeting consistently followed this profile. Scientific and technical centers were also targeted, and organizations outside of the political arena came under focus as well. Turla’s KopiLuwak activity does not necessarily focus on diplomatic/foreign affairs, and also winds down a different path. Instead, 2018 activity targeted government related scientific and energy research organizations, and a government related communications organization in Afghanistan. This highly selective but wider targeting set most likely will continue into 2019.

From the targeting perspective, we see closer ties between the KopiLuwak and WhiteBear activity, and closer alignments between Mosquito and Carbon activity.

And WhiteBear and KopiLuwak shared infrastructure while deploying unusual .js scripting. Perhaps open source offensive malware will become much more present in Mosquito and Carbon attacks as we see more meterpreter and injector code, and more uniquely innovative complex malware will continue to be distributed with KopiLuwak and a possible return of WhiteBear. And as we see with borrowed techniques from the previous zebrocy spearphishing, techniques are sometimes passed around and duplicated.

KopiLuwak: A New JavaScript Payload from Turla

Introducing WhiteBear

Gazing at Gazer [pdf]

APT Trends report Q2 2017

Diplomats in Eastern Europe bitten by a Turla mosquito [pdf]

The Epic Turla Operation

Peering into Turla’s second stage backdoor

Shedding Skin – Turla’s Fresh Faces