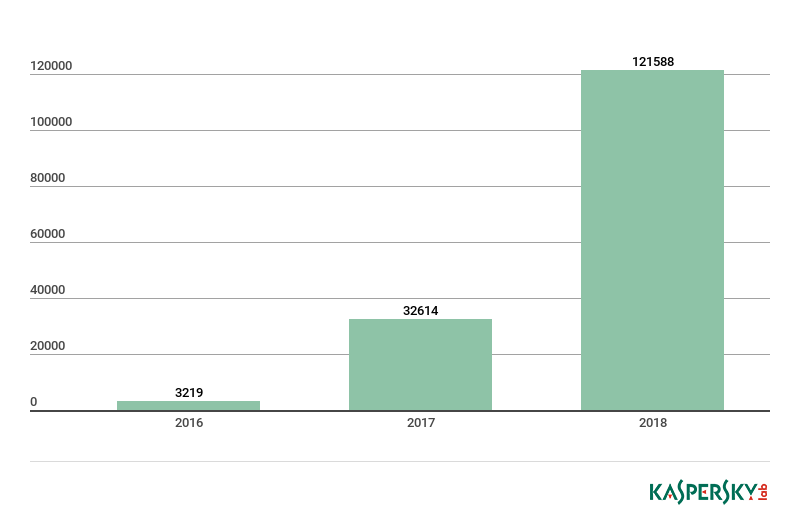

Cybercriminals’ interest in IoT devices continues to grow: in H1 2018 we picked up three times as many malware samples attacking smart devices as in the whole of 2017. And in 2017 there were ten times more than in 2016. That doesn’t bode well for the years ahead.

We decided to study what attack vectors are deployed by cybercriminals to infect smart devices, what malware is loaded into the system, and what it means for device owners and victims of freshly armed botnets.

Number of malware samples for IoT devices in Kaspersky Lab’s collection, 2016-2018.

One of the most popular attack and infection vectors against devices remains cracking Telnet passwords. In Q2 2018, there were three times as many such attacks against our honeypots than all other types combined.

| service | % of attacks |

| Telnet | 75.40% |

| SSH | 11.59% |

| other | 13.01% |

When it came to downloading malware onto IoT devices, cybercriminals’ preferred option was one of the Mirai family (20.9%).

| # | downloaded malware | % of attacks |

| 1 | Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.c | 15.97% |

| 2 | Trojan-Downloader.Linux.Hajime.a | 5.89% |

| 3 | Trojan-Downloader.Linux.NyaDrop.b | 3.34% |

| 4 | Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.b | 2.72% |

| 5 | Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.ba | 1.94% |

| 6 | Trojan-Downloader.Shell.Agent.p | 0.38% |

| 7 | Trojan-Downloader.Shell.Agent.as | 0.27% |

| 8 | Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.n | 0.27% |

| 9 | Backdoor.Linux.Gafgyt.ba | 0.24% |

| 10 | Backdoor.Linux.Gafgyt.af | 0.20% |

Top 10 malware downloaded onto infected IoT device following a successful Telnet password crack

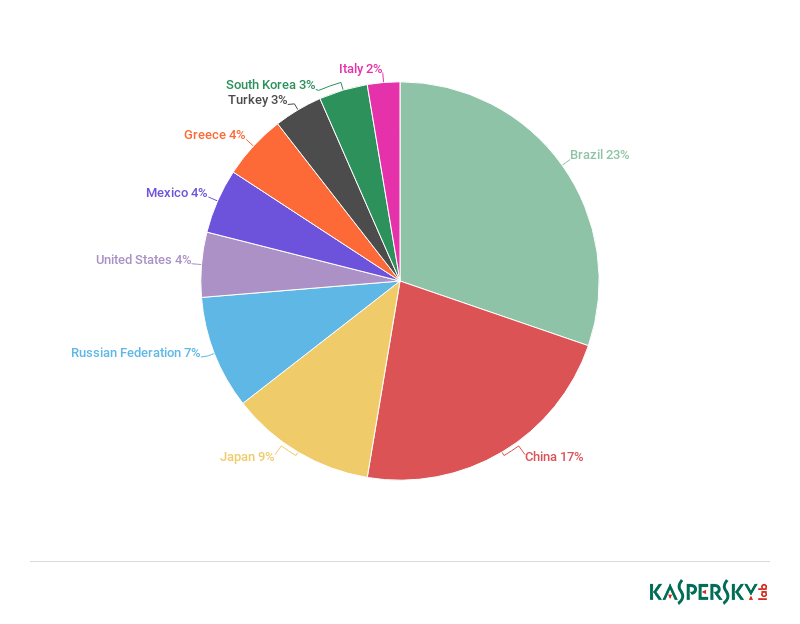

And here are the Top 10 countries from which our traps were hit by Telnet password attacks:

Geographical distribution of the number of infected devices, Q2 2018.

As we see, in Q2 2018 the leader by number of unique IP addresses from which Telnet password attacks originated was Brazil (23%). Second place went to China (17%). Russia in our list took 4th place (7%). Overall for the period January 1 – July 2018, our Telnet honeypot registered more than 12 million attacks from 86,560 unique IP addresses, and malware was downloaded from 27,693 unique IP addresses.

Since some smart device owners change the default Telnet password to one that is more complex, and many gadgets don’t support this protocol at all, cybercriminals are constantly on the lookout for new ways of infection. This is stimulated by the high competition between virus writers, which has led to password bruteforce attacks becoming less effective: in the event of a successful crack, the device password is changed and access to Telnet is blocked.

An example of the use of “alternative technology” is the Reaper botnet, whose assets at end-2017 numbered about 2 million IoT devices. Instead of bruteforcing Telnet passwords, this botnet exploited known software vulnerabilities:

- Vulnerabilities in D-Link 850L router firmware

- Vulnerabilities in GoAhead IP cameras

- Vulnerabilities in MVPower CCTV cameras

- Vulnerability in Netgear ReadyNAS Surveillance

- Vulnerability in Vacron NVR

- Vulnerability in Netgear DGN devices

- Vulnerabilities in Linksys E1500/E2500 routers

- Vulnerabilities in D-Link DIR-600 and DIR 300 – HW rev B1 routers

- Vulnerabilities in AVTech devices

Advantages of this distribution method over password cracking:

- Infection occurs much faster

- It is much harder to patch a software vulnerability than change a password or disable/block the service

Although this method is more difficult to implement, it found favor with many virus writers, and it wasn’t long before new Trojans exploiting known vulnerabilities in smart device software started appearing.

New attacks, old malware

To see which vulnerabilities are targeted by malware, we analyzed data on attempts to connect to various ports on our traps. This is the picture that emerged for Q2 2018:

| Service | Port | % of attacks | Attack vector | Malware families |

| Telnet | 23, 2323 | 82.26% | Bruteforce | Mirai, Gafgyt |

| SSH | 22 | 11.51% | Bruteforce | Mirai, Gafgyt |

| Samba | 445 | 2.78% | EternalBlue, EternalRed, CVE-2018-7445 | – |

| tr-069 | 7547 | 0.77% | RCE in TR-069 implementation | Mirai, Hajime |

| HTTP | 80 | 0.76% | Attempts to exploit vulnerabilities in a web server or crack an admin console password | – |

| winbox (RouterOS) | 8291 | 0.71% | Used for RouterOS (MikroTik) authentication and WinBox-based attacks | Hajime |

| Mikrotik http | 8080 | 0.23% | RCE in MikroTik RouterOS < 6.38.5 Chimay-Red | Hajime |

| MSSQL | 1433 | 0.21% | Execution of arbitrary code for certain versions (2000, 2005, 2008); changing administrator password; data theft | – |

| GoAhead httpd | 81 | 0.16% | RCE in GoAhead IP cameras | Persirai, Gafgyt |

| Mikrotik http | 8081 | 0.15% | Chimay-Red | Hajime |

| Etherium JSON-RPC | 8545 | 0.15% | Authorization bypass (CVE-2017-12113) | – |

| RDP | 3389 | 0.12% | Bruteforce | – |

| XionMai uc-httpd | 8000 | 0.09% | Buffer overflow (CVE-2018-10088) in XionMai uc-httpd 1.0.0 (some Chinese-made devices) | Satori |

| MySQL | 3306 | 0.08% | Execution of arbitrary code for certain versions (2000, 2005, 2008); changing administrator password; data theft | – |

The vast majority of attacks still come from Telnet and SSH password bruteforcing. The third most common are attacks against the SMB service, which provides remote access to files. We haven’t seen IoT malware attacking this service yet. However, some versions of it contain serious known vulnerabilities such as EternalBlue (Windows) and EternalRed (Linux), which were used, for instance, to distribute the infamous Trojan ransomware WannaCry and the Monero cryptocurrency miner EternalMiner.

Here’s the breakdown of possible infected IoT devices that replies on the IPs that attacked our honeypots in Q2 2018:

| Device | % of infected devices |

| MikroTik | 37.23% |

| TP-Link | 9.07% |

| SonicWall | 3.74% |

| AV tech | 3.17% |

| Vigor | 3.15% |

| Ubiquiti | 2.80% |

| D-Link | 2.49% |

| Cisco | 1.40% |

| AirTies | 1.25% |

| Cyberoam | 1.13% |

| HikVision | 1.11% |

| ZTE | 0.88% |

| Unspecified device | 0.68% |

| Unknown DVR | 31.91% |

As can be seen, MikroTik devices running under RouterOS are way out in front. The reason appears to be the Chimay-Red vulnerability. What’s interesting is that our honeypot attackers included 33 Miele dishwashers (0.68% of the total number of attacks). Most likely they were infected through the known (since March 2017) CVE-2017-7240 vulnerability in PST10 WebServer, which is used in their firmware.1

Port 7547

Attacks against remote device management (TR-069 specification) on port 7547 are highly common. According to Shodan, there are more than 40 million devices in the world with this port open. And that’s despite the vulnerability recently causing the infection of a million Deutsche Telekom routers, not to mention helping to spread the Mirai and Hajime malware families.

Another type of attack exploits the Chimay-Red vulnerability in MikroTik routers running under RouterOS versions below 6.38.4. In March 2018, it played an active part in distributing Hajime.

IP cameras

IP cameras are also on the cybercriminal radar. In March 2017, several major vulnerabilities were detected in the software of GoAhead devices, and a month after information about it was published, there appeared new versions of the Gafgyt and Persirai Trojans exploiting these vulnerabilities. Just one week after these malicious programs were actively distributed, the number of infected devices climbed to 57,000.

On June 8, 2018, a proof-of-concept was published for the CVE-2018-10088 vulnerability in the XionMai uc-httpd web server, used in some Chinese-made smart devices (for example, KKMoon DVRs). The next day, the number of logged attempts to locate devices using this web server more than tripled. The culprit for this spike in activity was the Satori Trojan, known for previously attacking GPON routers.

New malware and threats to end users

DDoS attacks

As before, the primary purpose of IoT malware deployment is to perpetrate DDoS attacks. Infected smart devices become part of a botnet that attacks a specific address on command, depriving the host of the ability to correctly handle requests from real users. Such attacks are still deployed by Trojans from the Mirai family and its clones, in particular, Hajime.

This is perhaps the least harmful scenario for the end user. The worst (and very unlikely) thing that can happen to the owner of the infected device is being blocked by their ISP. And the device can often by “cured” with a simple reboot.

Cryptocurrency mining

Another type of payload is linked to cryptocurrencies. For instance, IoT malware can install a miner on an infected device. But given the low processing power of smart devices, the feasibility of such attacks remains in doubt, even despite their potentially large number.

A more devious and doable method of getting a couple of cryptocoins was invented by the creators of the Satori Trojan. Here, the victim IoT device acts as a kind of key that opens access to a high-performance PC:

- At the first stage, the attackers try to infect as many routers as possible using known vulnerabilities, in particular:

- CVE-2014-8361 – RCE in the miniigd SOAP service in Realtek SDK

- CVE 2017-17215 – RCE in the firmware of Huawei HG532 routers

- CVE-2018-10561, CVE-2018-10562 – authorization bypass and execution of arbitrary commands on Dasan GPON routers

- CVE-2018-10088 – buffer overflow in XiongMai uc-httpd 1.0.0 used in the firmware of some routers and other smart devices made by some Chinese manufacturers

- Using compromised routers and the CVE-2018-1000049 vulnerability in the Claymore Etherium miner remote management tool, they substitute the wallet address for their own.

Data theft

The VPNFilter Trojan, detected in May 2018, pursues other goals, above all intercepting infected device traffic, extracting important data from it (user names, passwords, etc.), and sending it to the cybercriminals’ server. Here are the main features of VPNFilter:

- Modular architecture. The malware creators can fit it out with new functions on the fly. For instance, in early June 2018 a new module was detected able to inject javascript code into intercepted web pages.

- Reboot resistant. The Trojan writes itself to the standard Linux crontab job scheduler, and can also modify the configuration settings in the non-volatile memory (NVRAM) of the device.

- Uses TOR for communication with C&C.

- Able to self-destruct and disable the device. On receiving the command, the Trojan deletes itself, overwrites the critical part of the firmware with garbage data, and then reboots the device.

The Trojan’s distribution method is still unknown: its code contains no self-propagation mechanisms. However, we are inclined to believe that it exploits known vulnerabilities in device software for infection purposes.

The very first VPNFilter report spoke of around 500,000 infected devices. Since then, even more have appeared, and the list of manufacturers of vulnerable gadgets has expanded considerably. As of mid-June, it included the following brands:

- ASUS

- D-Link

- Huawei

- Linksys

- MikroTik

- Netgear

- QNAP

- TP-Link

- Ubiquiti

- Upvel

- ZTE

The situation is made worse by the fact that these manufacturers’ devices are used not only in corporate networks, but often as home routers.

Conclusion

Smart devices are on the rise, with some forecasts suggesting that by 2020 their number will exceed the world’s population several times over. Yet manufacturers still don’t prioritize security: there are no reminders to change the default password during initial setup or notifications about the release of new firmware versions, and the updating process itself can be complex for the average user. This makes IoT devices a prime target for cybercriminals. Easier to infect than PCs, they often play an important role in the home infrastructure: some manage Internet traffic, others shoot video footage, still others control domestic devices (for example, air conditioning).

Malware for smart devices is increasing not only in quantity, but also quality. More and more exploits are being weaponized by cybercriminals, and infected devices are used to steal personal data and mine cryptocurrencies, on top of traditional DDoS attacks.

Here are some simple tips to help minimize the risk of smart device infection:

- Don’t give access to the device from an external network unless absolutely necessary

- Periodic rebooting will help get rid of malware already installed (although in most cases the risk of reinfection will remain)

- Regularly check for new firmware versions and update the device

- Use complex passwords at least 8 characters long, including upper and lower-case letters, numerals, and special characters

- Change the factory passwords at initial setup (even if the device does not prompt you to do so)

- Close/block unused ports, if there is such an option. For example, if you don’t connect to the router via Telnet (port TCP:23), it’s a good idea to disable it so as to close off a potential loophole to intruders.

1 — The previous version of the text incorrectly stated that Kaspersky Lab honeypots, used for detecting botnets, were attacked by 33 Miele dishwashers.

A Miele representative shared new details with us so we could review our earlier findings.

We understand that connection attempts were performed by other objects from the networks that presented the targeted IP-addresses – including, but not limited to, a router or another device within the network.

We would like to thank the company for bringing this to our attention and being able to clarify our findings. We apologize for any confusion caused.

New trends in the world of IoT threats

Selene Gong

As a network engineer at router-switch.com, I’ve worked with many industrial and enterprise clients deploying IoT devices.

One common issue we continue to see — even in 2025 — is brute-force attacks over Telnet and SSH. These are still surprisingly effective when default credentials are left unchanged or remote access is exposed.

We always recommend:

1. Disabling Telnet and limiting SSH access to trusted subnets

2.Changing all default usernames/passwords

3.Keeping firmware up to date and monitoring for new CVEs

Awareness is improving, but it’s critical that installers and admins treat IoT with the same security mindset as traditional infrastructure.