A review from KasperskyOS developers

At Kaspersky Lab we analyze the technologies available on cybersecurity market and this time we decided to look at what OS developers are offering for embedded systems (or, in other words, the internet of things). Our primary interest is how and to what degree these OSs can solve cybersecurity-related issues.

We’d like to point out that this review reflects the author’s subjective opinion, and for the purposes of this analysis we developed our own classification of OSs.

Moreover, throughout this research we have compared other operating systems with KasperskyOS to see what we can learn from them and how we can improve KasperskyOS. The results of this comparison will also be presented in this article.

We analyzed a total of several dozen operating systems, from the most widespread to some niche players. The vast majority of the operating systems we looked at primarily handle practical functional tasks. Information security features, if they are included in the design, are merely extensions to the existing functionality in the form of plugins, components implementing encryption algorithms or add-in architecture. These measures can help improve the overall information security posture of a solution, but cannot guarantee protection from all modern threat models. If cybersecurity issues are not addressed in the initial design, it inevitably leads to compromises later when protection mechanisms are added.

Operating systems can be classified according to numerous criteria. Our approach was to treat operating systems from an architecture standpoint, so we classified them into four large classes according to their kernel types.

- monolithic systems,

- operating systems with monolithic kernels,

- microkernel-based operating systems,

- hybrid systems.

Monolithic systems

This is the most widespread type of operating system architecture for embedded devices. Most of the operating systems we analyzed are monolithic environments designed to work in microcontrollers where all processes (both user and system) run in a single address space without restrictions.

From an information security standpoint, this architecture is only suitable for very simple tasks – as the functionality becomes more complex, the risk of vulnerabilities becomes too great. Whenever vulnerabilities occur in such systems, whether it’s in implementations of system services or in an auxiliary application, this leads to the entire solution being compromised.

Libraries containing sets of encryption algorithms are usually offered as extra security measures for such operating systems. However, these measures can hardly be described as sufficient, because they don’t envisage a comprehensive solution to many important issues, such as the generation and storage of keys and certificates, ensuring trusted downloads, secure updates, etc. Also, because these libraries are created specifically for the appropriate operating systems, they often don’t undergo verification and/or sufficient testing, so they themselves may contain vulnerabilities and therefore reduce (rather than improve) the overall security of the solutions they’re part of.

Other measures (such as stack protection, various types of additional checks etc.) may ensure protection against different types of failures and errors, but they are often useless at protecting against targeted attacks that exploit known vulnerabilities within the system.

Even if a microkernel architecture was formally applied in a solution like this, an acceptable level of protection is impossible to ensure unless user processes are isolated from system processes, since any user process could affect the operation of the microkernel. Examples of microkernel operating systems in which processes are not isolated properly include the popular RIOT OS, Zephyr, Unison RTOS, and even the commercial microcontroller kernel µ-velOSity provided by Green Hills, as well as Microsar OS, the basic operating system for automotive solutions provided by Vector.

Despite all the security shortcomings of monolithic systems, such compact operating systems are suitable for work in cheap microcontrollers. They can be used in simple and compact devices where the only task is to measure a single parameter, such as temperature, pressure, volume, etc. Devices like these must be simple, compact and cheap. In our view, monolithic systems are not the best option when faced with tasks that are more complex.

Monolithic kernel systems

Monolithic kernel systems are another type of operating system architecture. This is perhaps the most widespread and popular type of operating system architecture both for embedded systems and for general-purpose systems (i.e. servers, workstations and mobile devices.)

Unlike in purely monolithic solutions, user processes in monolithic kernel systems are isolated from the kernel and only have access to its functions via a limited number of system calls. This constitutes a serious advantage from the information security standpoint.

A large number of services run in the kernel context, such as protocol implementations, file systems, device drivers, etc. Examples of monolithic kernel operating systems include those based on the Linux kernel (and its derivatives), as well as Windows, FreeBSD, RTEMS, etc.

The operating system’s kernel services still leave a large attack surface, while the code base operating in the kernel context cannot be considered as trusted. Therefore, don’t expect the kernel services to be free from vulnerabilities (in fact, vulnerabilities are regularly detected).

The compromise of any kernel service inevitably leads to the entire system being compromised, no matter what tools are employed to protect it.

The second problem is especially relevant for embedded systems. It is the need to restart the device when kernel models are updated. Indeed, restarting is not always required, however any case when a restart is not required is the exception rather than the rule.

The main advantage of monolithic kernel architecture is its better performance as compared to microkernel operating systems. This is due to the smaller number of context switches.

Different Linux distributions

Operating systems based on the Linux kernel are very user-friendly: they are available in source code, offer excellent hardware support and have a large amount of application and system software. All this makes these operating systems extremely attractive for developers of embedded systems.

Note: Linux only serves as the kernel of an operating system. Full-fledged operating systems are Linux-based distributions.

It’s worth noting that Linux was developed as a kernel for a multi-user operating system and contains a set of built-in security mechanisms, but from a modern-day perspective it has a number of information security issues, both in terms of architecture and implementation.

Conventional wisdom suggests that a properly configured Linux-based solution is sufficiently secure. However, the actual configuration process is quite complicated and most security restrictions can be bypassed. Besides, there are also difficulties with Linux that are related to the implementation of secure boot mechanisms, updating operating system components, and a multitude of other problems.

A large number of Linux-based branches and distributions have been developed that aim to improve security. Extensions have also been developed to tackle information security issues, including AppArmour, GRSecurity, PAX, SELinux, etc. These extensions help improve the security posture, though they cannot guarantee sufficient security, because the code base of the Linux kernel is quite large, and there’s no way of making the kernel’s computing base trusted. This problem appears to be insurmountable. According to www.cvedetails.com, 453 vulnerabilities were detected in Linux kernels in 2017. That number includes 159 vulnerabilities that allow execution of arbitrary code in the kernel context. Exploitation of a vulnerability in the Linux kernel makes it possible to circumvent any protection mechanisms, even the most sophisticated and carefully configured.

Android

Android 8.0 Oreo is the latest version of the Android operating system for mobile devices and, according to the developers, contains a multitude of new information security mechanisms. The key security features in this operating system are aimed at mitigating the consequences of exploiting vulnerabilities and reducing the attack surface, as well as the use of the principle of least privilege. There have also been changes to the API design and to the architecture. Some of the innovations are described below:

- Smart protection of app authorization.

- Advanced verification during updates of applications and the operating system to prevent common types of attacks, including rollback.

- In-built support of HSM (hardware security module).

- Application sandboxing with support for seccomp filters (secure computing restricts apps’ ability to make system calls) and the WebView component is isolated.

- Support for a set of encryption profiles (different profiles use different sets of keys).

- In-built support for two-factor authentication using physical keys.

- Complicating paths to apps. An app can no longer be found at its static location. Instead, it is installed each time to a new location, and a special call to the system must be made to gain access to the app.

- Discontinued support of outdated and vulnerable protocols and algorithms, such as SSL v3.0.

These are all necessary and useful measures that substantially complicate post exploitation of vulnerabilities and the ability to gain root privileges.

However, it shouldn’t be forgotten that the Linux kernel is inside Android with all the drawbacks inherent to it. An analysis of the monthly security bulletins shows that new vulnerabilities are being discovered in Android all the time, and a significant portion of them enable execution of arbitrary code.

Microkernel operating systems

One possible solution to the above problems is the use of microkernel architecture.

A microkernel provides only the elementary functions of process management and a minimum set of hardware abstractions. Most of the work is done with the help of dedicated user processes that don’t run in the kernel’s address space. This helps to substantially reduce the attack surface of the kernel services, while the kernel of the operating system can be rigorously verified (thanks to the small code base) using, among other things, formal verification methods. To learn more about verification and how it is different from validation, check out Ekaterina Rudina’s article devoted to this topic.

The most meaningful results from an information security standpoint have been shown for microkernel architectures, for example, the Separation Kernel approach and the use of MILS architecture.

Different types of microkernels and microkernel operating systems are widely available on the market. Some examples from this category are QNX, INTEGRITY RTOS, Genode, the L4 kernel and its derivatives.

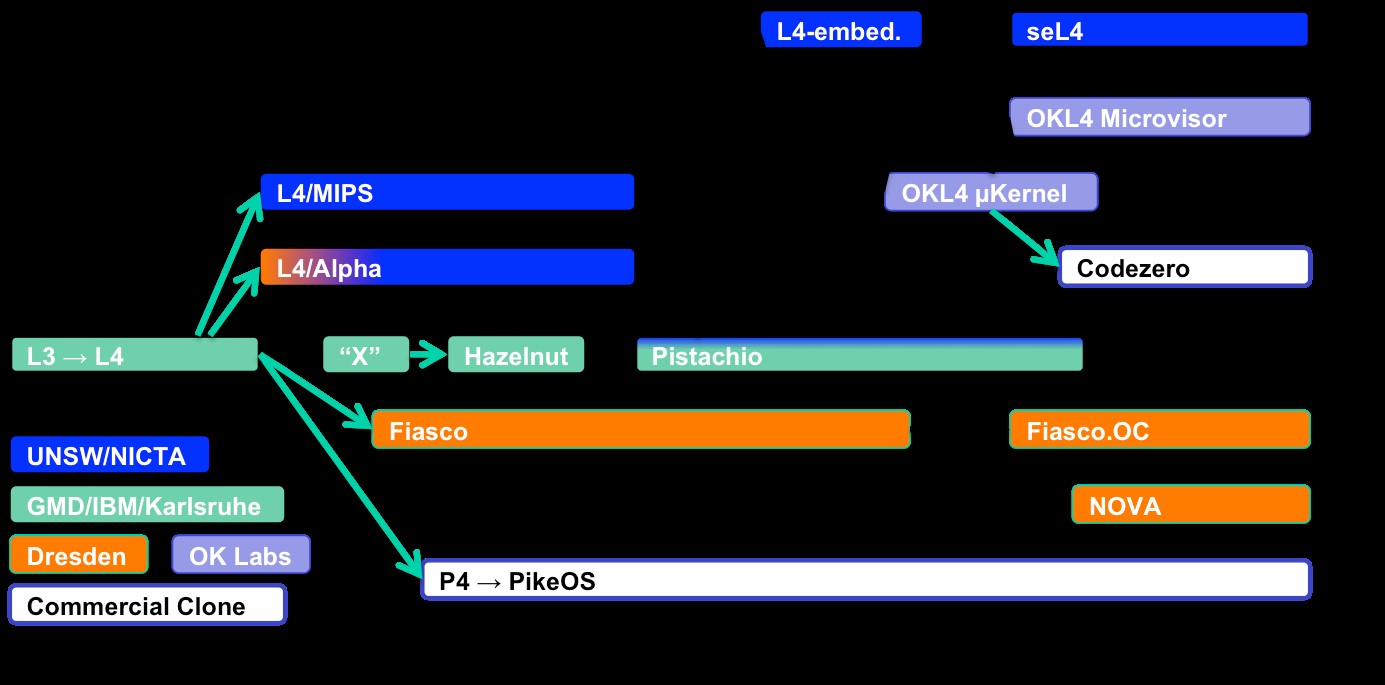

We would like to dwell a little bit on the microkernel L4. It’s the result of an evolutionary process in the microkernel approach to the development of operating systems. Today, L4 is effectively the de facto standard in the development of microkernel operating systems.

L4 microkernel family

The L4 kernel was initially developed to demonstrate the feasibility of creating a microkernel that is suitable for use in real-life, general-purpose operating systems. This attempt can be considered rather successful: there now exists a whole family of research and commercial projects that make use of the L4 derivatives. The kernels of this family have been ported on a large number of hardware platforms. It should be noted that solutions based on L4 support operation in hard real-time mode.

Among the microkernel implementations currently supported the following can be highlighted:

- seL4 – the first microkernel to be formally verified. It is still undergoing active development.

- Codezero – a commercial version of the K4 kernel. The source code of the kernel is available under GPLv3 license, while the source of the additional modules and libraries is closed and distributed under commercial licenses.

- OC – a version developed by TU Dresden and distributed under GPLv2 license; commercial support is available.

For the listed operating systems, there are different virtualization solutions available. There are also other virtualization solutions based on the L4 microkernel that are worth mentioning – they are OKL4, NOVA and the PikeOS operating system.

The microkernels of the L4 family are also used in the following operating systems:

- Genode

- TUD:OS – an operating system developed by TU Dresden on the basis of L4Re, which is an L4-based framework for constructing solutions.

- CAamkES – a framework based on the L4 microkernel that was developed by Trustworthy Systems Research Group @Data61.

- L4Linux – a porting of the Linux operating system based on the L4-family kernel. In this implementation of L4, Linux plays the role of a user mode service operating simultaneously with other L4 applications (including real-time components). Linux kernel versions up to 4.14 and hardware platforms x86 and ARM are supported.

From a security point of view, the seL4 kernel is the most important member of the L4 family.

The microkernel seL4 implements an object-capability model. Formal verification has been conducted for it, meaning the operating system’s properties can be guaranteed within specified concepts and assumptions; this improves the overall protection status of the solution. However, if the input assumptions are incorrect, problems can arise. For instance, a substantial drawback of the formal model during seL4 verification is that it rules out simultaneous execution of several processes (a single-processor system with blocked interruptions is envisaged).

The object-capability model provides detailed control over system behavior, but by no means all security properties can be described with its help. There are numerous other security models whose properties are impossible to express based on the object-capability model. For example, security properties may depend on system status, take time relationships into account, etc. To describe such properties, extra mechanisms need to be added to the solution, and in that case the advantages of seL4 are lost.

KasperskyOS makes use of many of the ideas used in seL4. However, it also allows for a description of any security properties by using Kaspersky Security System (KSS), part of the KasperskyOS architecture.

Hybrid operating systems

A hybrid kernel exhibits a combination of properties typical of monolithic and microkernel architectures; a hybrid kernel-based operating system architecture is essentially a modified microkernel that allows operating system modules to be executed in the kernel space to expedite operation.

Operating systems with hybrid kernels have emerged as a result of attempts to use the advantages of microkernel architecture while retaining as much of the well-tested monolithic kernel code as possible. In operating systems of this class, however, the problem of information security remains unsolved, because the attack surface remains large.

The ‘secure by design’ requirement

Many of the older operating systems were initially developed with no regard for information security. When security features are introduced, functional mechanisms cease to operate as they did before, and compatibility issues arise. For this reason, and a host of others, it’s impossible to completely revisit the architectures of these systems, and there can be no security guarantees – it’s only possible to talk of enhancing some security-related properties. There are many examples of such solutions, including QNX, Linux, and FreeBSD.

Only those operating systems that took information security requirements into consideration during development can ensure proper implementation of security mechanisms without impacting their functional capabilities. The use of a secure-by-design approach is a key requirement for the final solution to be certified to Common Criteria standard, starting with EAL4. Examples of secure-by-design operating systems are seL4, INTEGRITY RTOS, MUEN RTOS, KasperskyOS and several others.

KasperskyOS

From the very start, KasperskyOS was created to meet the most rigid information security requirements. It was based on advanced practices and approaches to creating secure systems, in line with the requirements of all essential security standards. In light of this, KasperskyOS can be considered a truly secure operating system from its inception.

KasperskyOS uses microkernel architecture in which the microkernel system tools divide the system into security domains, or ‘entities’ in KasperskyOS terms. All communications between security domains (inter-process communications, IPC) are performed using the microkernel – and controlled by it. No communications are allowed to bypass the microkernel.

All communications are typed: the interface of the entities is described in IDL (Interface Definition Language), and only this interface can be used for IPCs. This is where KasperskyOS differs significantly from most other operating systems.

The KasperskyOS microkernel operates in conjunction with Kaspersky Security System (KSS), which is a subsystem that calculates security verdicts. For each IPC, the KasperskyOS microkernel requests a verdict from KSS, which it uses as a basis for permitting or blocking that particular IPC. For verdict calculation, it is not only the fact and type of communication that is taken into account but also the system’s topology, the context in which the communication takes place, as well as the assigned policy described within the framework of a set of formal security models.

KSS supports a large number of formal security models, for example, Domain Type Enforcement, Object Capability, Role-Based Access, diverse temporal logic dialects, etc. New models can be added when required.

This provides the developer with a flexible tool to describe security policies with as high a level of detail as required. We are not aware of any other solution that provides this degree of detail.

Security policies are defined in a high-level language, which greatly simplifies the verification of the solution in accordance with stipulated requirements. This also makes it possible to run formal verification of the described properties[1].

If we consider systems with limited functional capabilities that perform a limited set of functions, theoretically it’s possible to provide the specified security properties and guarantee there are no vulnerabilities in the software code.

As a solution grows progressively more complex, the addition of different protocols, algorithms, functions, etc. makes it impossible to guarantee there are no vulnerabilities in it. Special measures must be taken to ensure these vulnerabilities cannot be exploited or that their exploitation does not lead to undesirable consequences. These protection measures should include isolation of processes, restricted access to resources, attack detection systems and countermeasures, etc. In that case, the security properties must be guaranteed by the system’s trusted components, i.e., by the OS kernel, security features, subsystems providing specific types of protection, such as cryptographic protection, etc.

At the same time, the relevant security policies need to be defined in an increasingly detailed way, and there comes a point when the capabilities of policy refinement reach a limit. For example, capability-based policies can allow or deny access to a certain resource, though there is no ability to define a situation in which such access would be contingent on something. In such cases, the required security properties are considered functional requirements, and are implemented in the solution’s code along with its other features. This leads to a progressive growth in the volume of the code base that needs to be controlled, and ensuring its verifiability becomes an increasingly challenging task. Consequently, the solution again becomes insecure.

With the help of KasperskyOS and KSS, it’s possible to provide as detailed a description of security properties as desired, and through decomposition of the solution it’s possible to select a limited set of individual modules containing the minimum required functions that require verification. These modules can be viewed as standalone and isolated – their verification then becomes easy.

The code base of KSS responsible for implementing the solution’s security policies can be generated, is formally verifiable[2] and, in this sense, it is trusted. This solves the problem of uncontrolled growth of the code base to which requirements of trust are imposed.

Since security properties are defined regardless of the functional logic, the developer can construct a security system for their solutions without taking into account the details of how specific components are implemented.

The described capabilities of KasperskyOS make it possible to follow a natural course of developing secure solutions that includes the following steps:

- Threat analysis and threat modeling.

- Development of a set of formal security policies to counter the threats described in step 1.

- Decomposition of the solution into security domains, and definition of IPC interfaces in line with the data obtained at step 2.

- Implementation of the solution in line with the data obtained at step 3, and configuration of security policies aligned with the results obtained at step 2.

The ability to follow the described process of development is an important methodological advantage over other operating systems. This ensures a key advantage of KasperskyOS: complex systems can be built to meet specific information security characteristics.

KasperskyOS supports virtualization with the help of the Kaspersky Secure Hypervisor (KSH) application. Its key feature is that it can work together with KSS to implement security policies related to the control of virtual machine access to the hypervisor’s internal resources. KSH is a lightweight solution. This makes it possible to verify its code base and means it can be viewed as being part of a trusted platform. The hypervisor can apply KSS verdicts to its internal processes even in situations where cross-domain interaction does not take place.

This capability does not exist in any other virtualization solutions; it is only possible to set rules to define how a specific virtual machine interacts with other isolated components of the system.

Conclusion

Now, in the internet-of-things era, cybersecurity issues surrounding connected devices are becoming increasingly critical. In our opinion, it is the security of the operating system that defines the overall level of cybersecurity of an entire embedded system. Unfortunately, issues of information security are still not given sufficient consideration during the development of operating systems. For nearly half of the operating systems we have considered, information security aspects are either not addressed whatsoever, or the functions associated with information security are implemented at a level that is unsatisfactory.

We hope that this review will, firstly, encourage the developers of operating systems for embedded systems to devote more attention to issues of cybersecurity, and, secondly, help developers choose an operating system for their projects. After all, it’s important for all of us that the internet of things doesn’t grow into an internet of threats.

[1] No formal verification of KSS has been performed as of yet; however, the approach employed allows for it.

[2] At this time, the requirement of formal verifiability is not met; however, there are vigorous efforts being made towards this end.

Modern OSs for embedded systems

RIYAD AMIN

Absolutely excellent