Targeted attacks and malware campaigns

Operation AppleJeus: the sequel

In 2018, we published a report on Operation AppleJeus, one of the more notable campaigns of the threat actor Lazarus, currently one of the most active and prolific APT groups. One notable feature of this campaign was that it marked the first time Lazarus had targeted macOS targets, with the group inventing a fake company in order to deliver its manipulated application and exploit the high level of trust among potential victims.

Our follow-up research revealed significant changes to the group’s attack methodology. To attack macOS victims, Lazarus has developed homemade macOS malware and added an authentication mechanism to deliver the next stage payload very carefully, as well as loading the next-stage payload without touching the disk. In addition, to attack Windows victims, the group has elaborated a multi-stage infection procedure and made significant changes to the final payload. We believe Lazarus has been more careful in its attacks since the release of Operation AppleJeus and has employed a number of methods to avoid detection.

We identified several victims as part of our ongoing research, in the UK, Poland, Russia and China. Moreover, we were able to confirm that several of the victims are linked to cryptocurrency business organizations.

Roaming Mantis turns to SMiShing and enhances anti-researcher techniques

Kaspersky continues to track the Roaming Mantis campaign. This threat actor was first reported in 2017, when it used SMS to distribute its malware to Android devices in just one country – South Korea. Since then, the scope of the group’s activities has widened considerably. Roaming Mantis now supports 27 languages, targets iOS as well as Android and includes cryptocurrency mining for PCs in its arsenal.

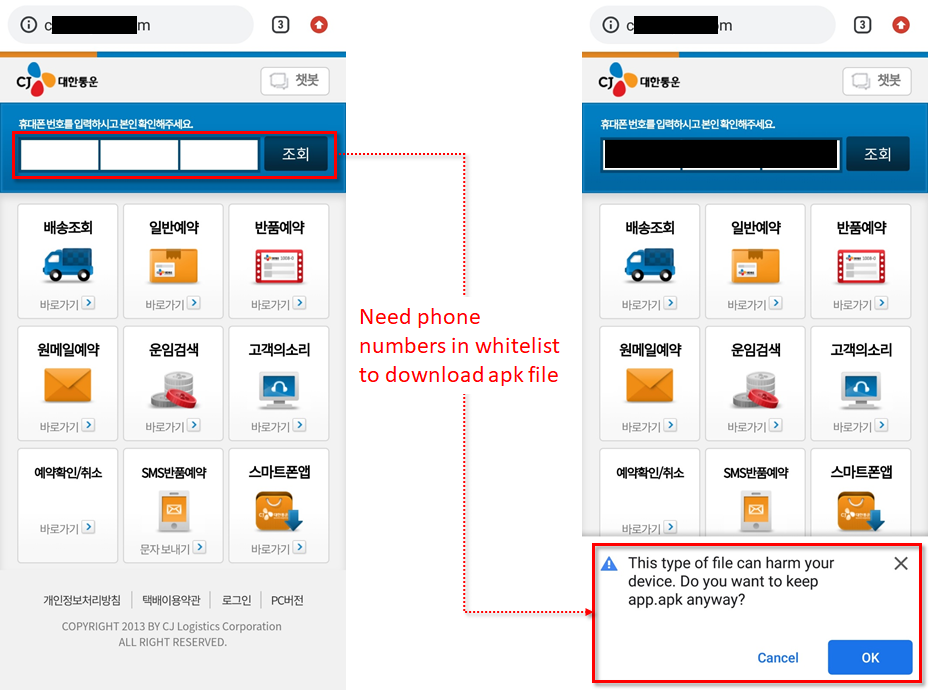

Roaming Mantis is strongly motivated by financial gain and is continuously looking for new targets. The group has also put a lot of effort into evading tracking by researchers, including implementing obfuscation techniques and using allowlisting to avoid infecting researchers who navigate to the malicious landing page. While the group is currently applying allowlisting only to Korean pages, we think it is only a matter of time before Roaming Mantis implements this for other languages.

Roaming Mantis has also added new malware families, including Fakecop and Wroba.j. The actor is still very active in using ‘SMiShing‘ for Android malware distribution. This is particularly alarming, because it means that the attackers could combine infected mobile devices into a botnet for malware delivery, SMiShing, and so on. In one of the more recent methods used by the group, a downloaded malicious APK file contains an icon that impersonates a major courier company brand: the spoofed brand icon is customized for the country it targets – for example, Sagawa Express for Japan, Yamato Transport and FedEx for Taiwan, CJ Logistics for South Korea and Econt Express for Russia.

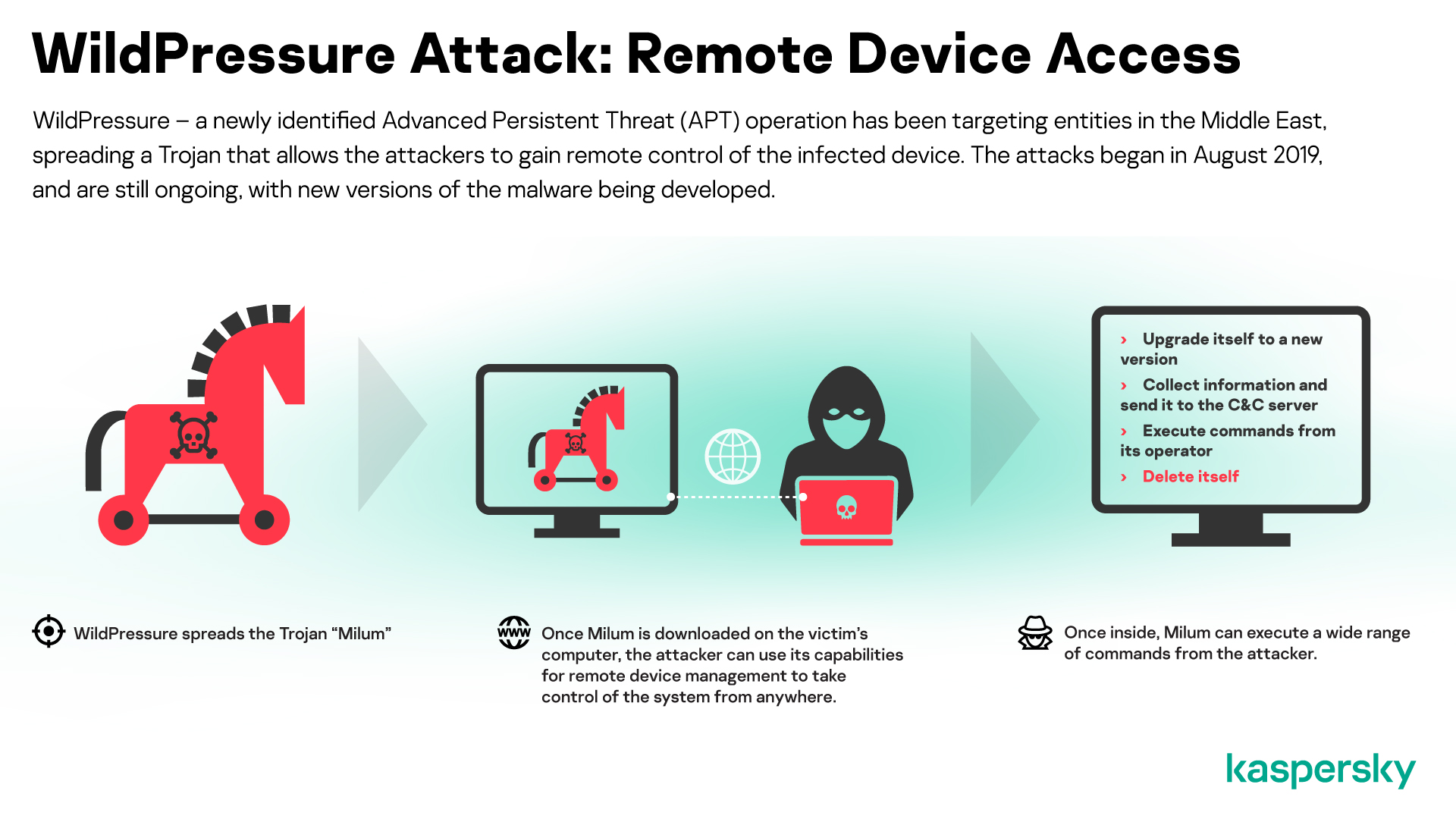

WildPressure on industrial networks in the Middle East

In March, we reported a targeted campaign to distribute Milum, a Trojan designed to gain remote control of devices in target organizations, some of which operate in the industrial sector. We detected the first signs of this operation, which we have dubbed WildPressure, in August 2019; and the campaign remains active.

The Milum samples that we have seen so far do not share any code similarities with any known APT campaigns. All of them allow the attackers to control infected devices remotely: letting them download and execute commands, collect information from the compromised computer and send it to the C2 server and install upgrades to the malware.

Attacks on industrial targets can be particularly devastating. So far, we haven’t seen evidence that the threat actor behind WildPressure is trying to do anything beyond gathering data from infected networks. However, the campaign is still in development, so we don’t yet know what other functionality might be added.

To avoid becoming a victim of this and other targeted attacks, organizations should do the following.

- Update all software regularly, especially when a new patch becomes available.

- Deploy a security solution with a proven track record, such as Kaspersky Endpoint Security, that is equipped with behavior-based protection against known and unknown threats, including exploits.

- On top of endpoint protection, implement a corporate-grade security solution designed to detect advanced threats against the network, such as Kaspersky Anti Targeted Attack Platform.

- Ensure staff understand social engineering and other methods used by attackers and develop a security culture within in the organization.

- Provide your security team with access to comprehensive cyberthreat intelligence, such as Kaspersky APT Intelligence Reporting.

TwoSail Junk

On January 10, we discovered a watering-hole attack that utilized a full remote iOS exploit chain to deploy a feature-rich implant named LightSpy. Judging by the content of the landing page, the site appears to have been designed to target users in Hong Kong.

Since then, we have released two private reports on LightSpy, available to customers of Kaspersky Intelligence Reporting (please contact intelreports@kaspersky.com for further information).

We are temporarily calling the APT group behind this implant TwoSail Junk. Currently, we have hints from known backdoor callbacks to infrastructure about clustering this campaign with previous activity. We are also working with fellow researchers to tie LightSpy to prior activity from a well-established Chinese-speaking APT group, previously reported (here and here) as Spring Dragon (aka Lotus Blossom and Billburg(Thrip)), known for its Lotus Elise and Evora backdoors.

As this LightSpy activity was disclosed publicly by fellow researchers from Trend Micro, we wanted to contribute missing information to the story without duplicating content. In addition, in our quest to secure technologies for a better future, we have reported this malware and activity to Apple and other relevant companies.

Our report includes information about the Android implant, including its deployment, spread and support infrastructure.

A sprinkling of Holy Water in Asia

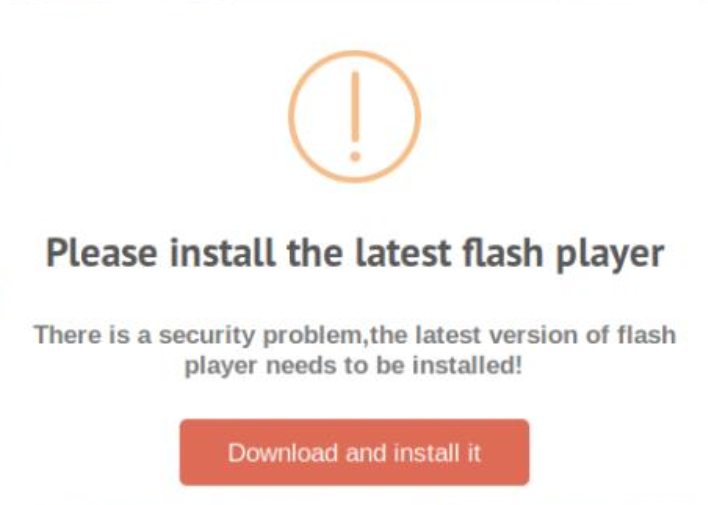

In December, we discovered watering-hole websites that were compromised to selectively trigger a drive-by download attack with fake Adobe Flash update warnings.

This campaign, which has been active since at least May 2019, targets an Asian religious and ethnic group. The threat actor’s unsophisticated but creative toolset, which has evolved greatly and may still be in development, makes use of Sojson obfuscation, NSIS installer, Python, open-source code, GitHub distribution, Go language and Google Drive-based C2 channels.

The threat actor’s operational target is unclear because we haven’t been able to observe many live operations. We have also been unable to identify any overlap with known APT groups.

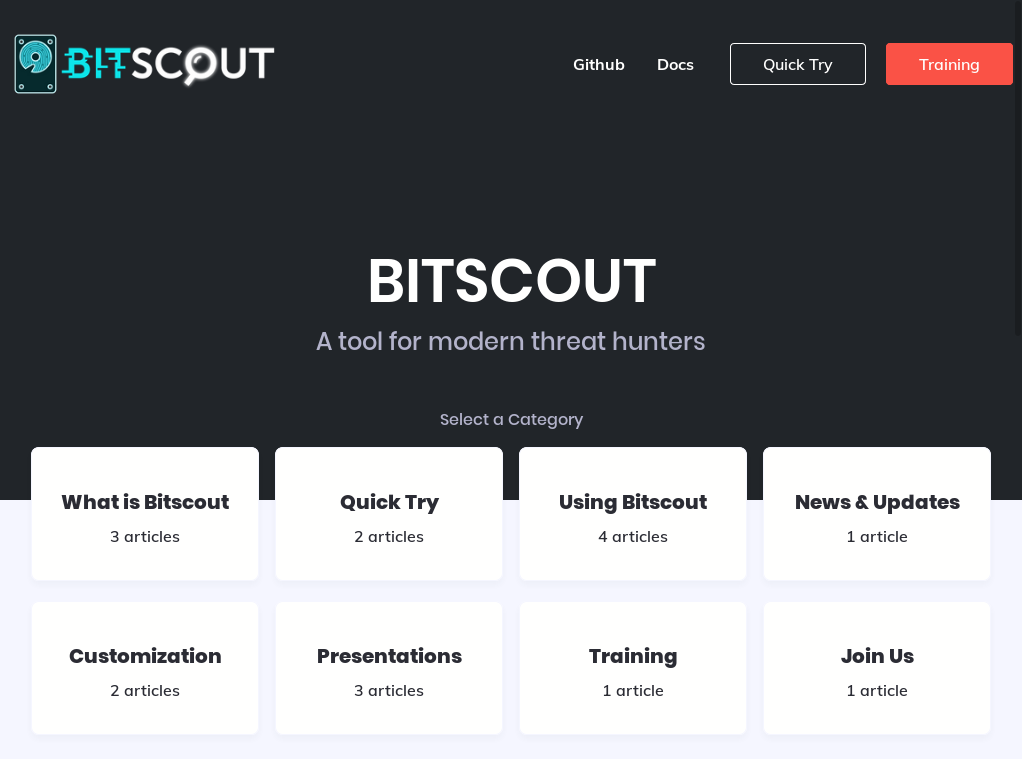

Threat hunting with Bitscout

In February, Vitaly Kamluk, from the Global Research and Analysis Team at Kaspersky, reported on a new version of Bitscout, based on the upcoming release of Ubuntu 20.04 (scheduled for release in April 2020).

Bitscout is a remote digital forensics tool that we open-sourced about two and a half years ago, when Vitaly was located in the Digital Forensics Lab at INTERPOL. Bitscout has helped us in many cyber-investigations. Based on the widely popular Ubuntu Linux distribution, it incorporates forensics and malware analysis tools created by a large number of excellent developers around the world.

Here’s a summary of the approach we use in Bitscout

- Bitscout is completely FREE, thereby reducing your forensics budget.

- It is designed to work remotely, saving time and money that would otherwise be spent on travel. Of course, you can use the same techniques locally.

- The true value lies not in the toolkit itself, but in the power of all the forensic tools that are included.

- There’s a steep learning curve involved in mastering Bitscout, which ultimately reinforces the technical foundations of your experts.

- Bitscout records remote forensics sessions internally, making it perfect for replaying and learning from more experienced practitioners or using as evidential proof of discovery.

- It is fully open source, so you don’t need to wait for the vendor to implement a patch or feature for you: you are free to reverse-engineer and modify any part of it.

We have launched a project website, bitscout-forensics.info, as the go-to destination for those looking for tips and tricks on remote forensics using Bitscout.

Hunting APTs with YARA

In recent years, we have shared our knowledge and experience of using YARA as a threat hunting tool, mainly through our training course, ‘Hunting APTs with YARA like a GReAT ninja’, delivered during our Security Analyst Summit. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced us to postpone the forthcoming SAS.

Meanwhile, we have received many requests to make our YARA hands-on training available to more people. This is something we are working on and hope to be able to provide soon as an online training experience. Look out for updates on this by following us on Twitter – @craiu, @kaspersky.

With so many people working from home, and spending even more time online, it is also likely the number of threats and attacks will increase. Therefore, we decided to share some of the YARA experience we have accumulated in recent years, in the hope that all of you will find it useful for keeping threats at bay.

If you weren’t able to join the live presentation, on March 31, you can find the recording here.

We track the activities of hundreds of APT threat actors and regularly highlight the more interesting findings here. However, if you want to know more, please reach out to us at intelreports@kaspersky.com

Other security news

Shlayer Trojan attacks macOS users

Although many people consider macOS to be safe, there are cybercriminals who seek to exploit those who use this operating system. One malicious program stands out – the Shlayer Trojan. In 2019, Kaspersky macOS products blocked this Trojan on every tenth device, making this the most widespread threat to people who use macOS.

Shlayer is a smart malware distribution system that spreads via a partner network, entertainment websites and even Wikipedia. This Trojan specializes in the installation of adware – programs that feed victims illicit ads, intercepting and gathering their browser queries and modifying search results to distribute even more advertising messages.

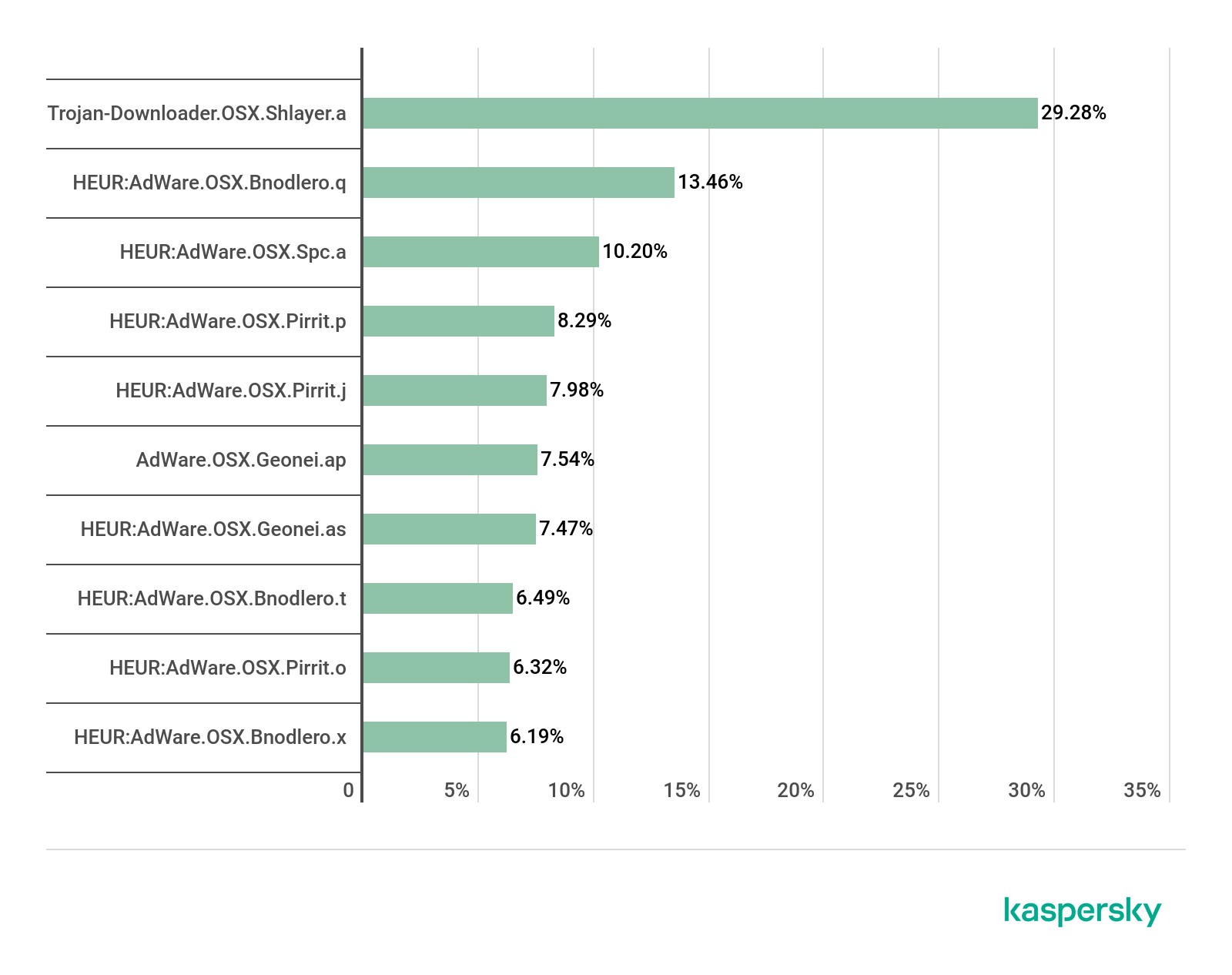

Shlayer accounted for almost one-third of all attacks on macOS devices registered by Kaspersky products between January and November last year – and nearly all other top 10 macOS threats were adware programs that Shlayer installs.

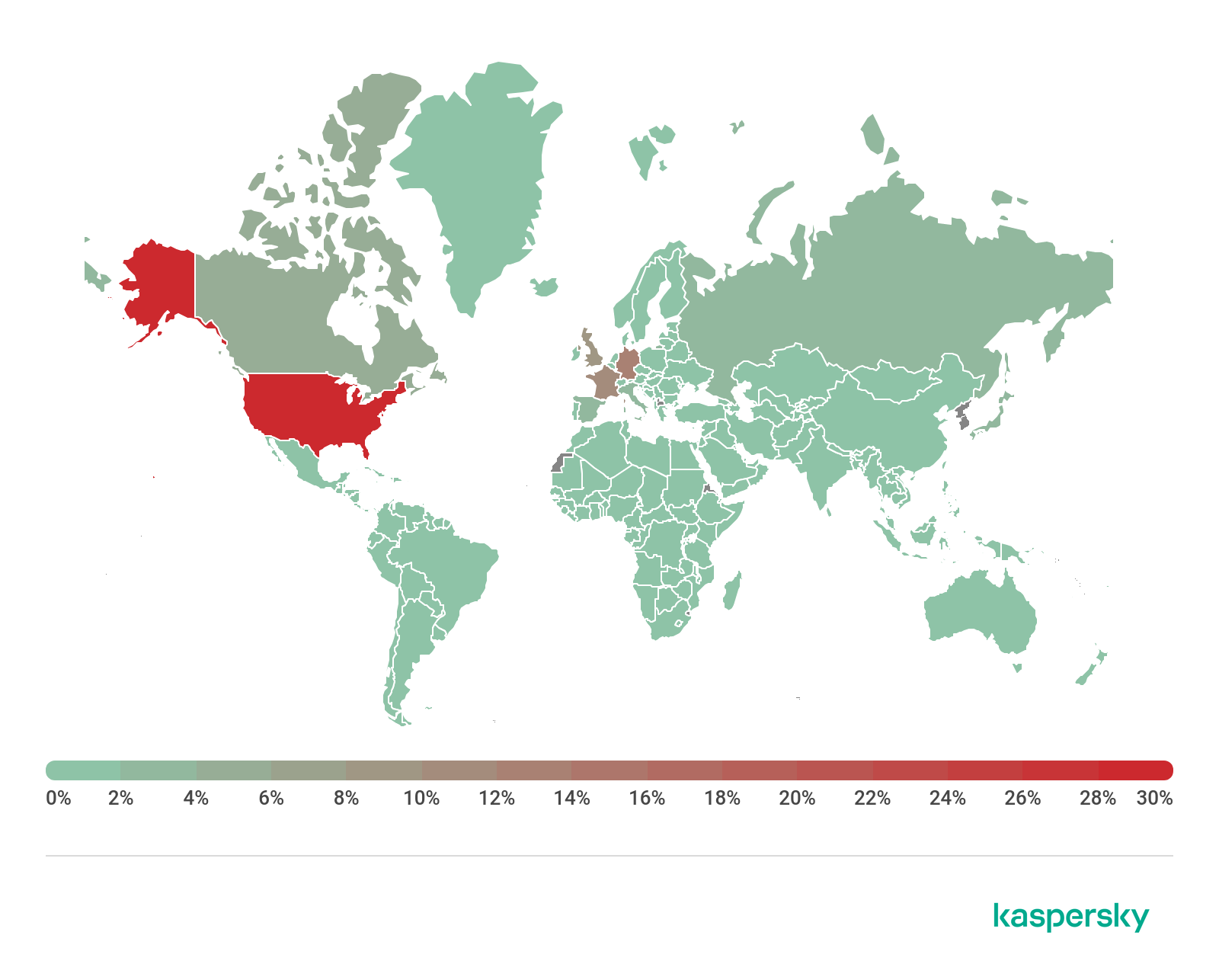

The infection starts with an unwitting victim downloading the malicious program. The criminals behind Shlayer set up a malware distribution system with a number of channels leading their victims to download the malware. Shlayer is offered as a way to monetize websites in a number of file partner programs, with relatively high payment for each malware installation made by users in the US, prompting over 1,000 ‘partner sites’ to distribute Shlayer. This scheme works as follows: a user looks for a TV series episode or a football match, and advertising landing pages redirect them to fake Flash Player update pages. From here, the victim downloads the malware; and for each installation, the partner who distributed links to the malware receives a pay-per-install payment.

Other schemes that we saw led to a fake Adobe Flash update page that redirected victims from various large online services with multi-million audiences, including YouTube, where links to the malicious website were included in video descriptions, and Wikipedia, where such links were hidden in article references. People that clicked on these links would also be redirected to the Shlayer download landing pages. Kaspersky researchers found 700 domains containing malicious content, with links to them on a variety of legitimate websites.

Almost all the websites that led to a fake Flash Player contained content in English. This corresponds to the countries where we have seen most infections – the US (31%), Germany (14%), France (10%) and the UK (10%).

Blast from the past

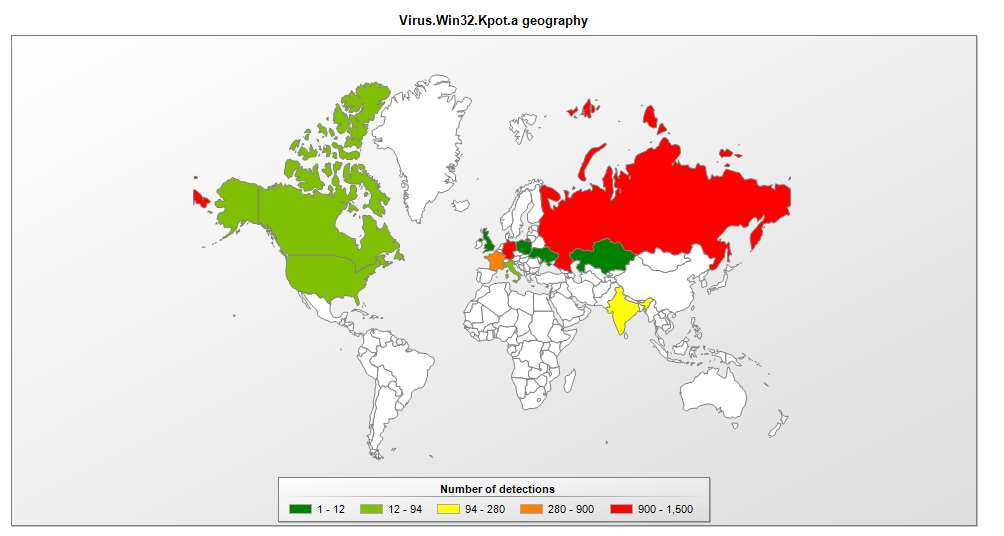

Although many people still use the term “virus” to mean any malicious program, it actually refers specifically to self-replicating code, i.e., malicious code that copies itself from file to file on the same computer. Viruses, which used to dominate the threat landscape, are now rare. However, there are some interesting exceptions to this trend and we came across one recently – the first real virus we’ve seen in the wild for some time.

The virus, called KBOT, infects the victim’s computer via the internet, a local network, or infected external media. After the infected file is launched, the malware gains a foothold in the system, writing itself to Startup and the Task Scheduler, and then deploys web injects to try to steal the victim’s bank and personal data. KBOT can also download additional stealer modules that harvest and send to the Command-and-Control (C2) server comprehensive information about the victim, including passwords/logins, crypto-wallet data, lists of files and installed applications, and so on. The malware stores all its files and stolen data in a virtual file system, encrypted using the RC6 algorithm, making it hard to detect.

Cybercriminals exploiting fears about data breaches

Phishers are always on the lookout for hot topics that they can use to hook their victims, including sport, politics, romance, shopping, banking, natural disasters and anything else that might entice someone into clicking on a link or malicious file attachment.

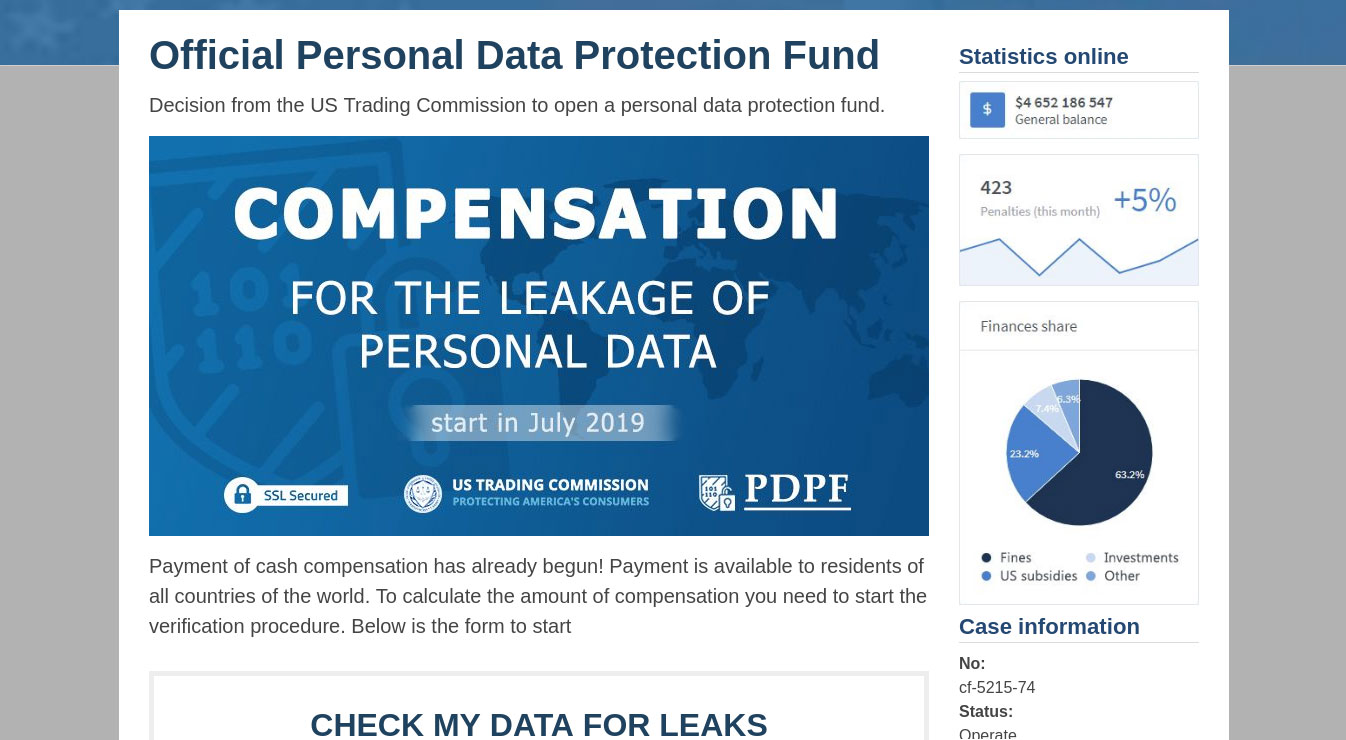

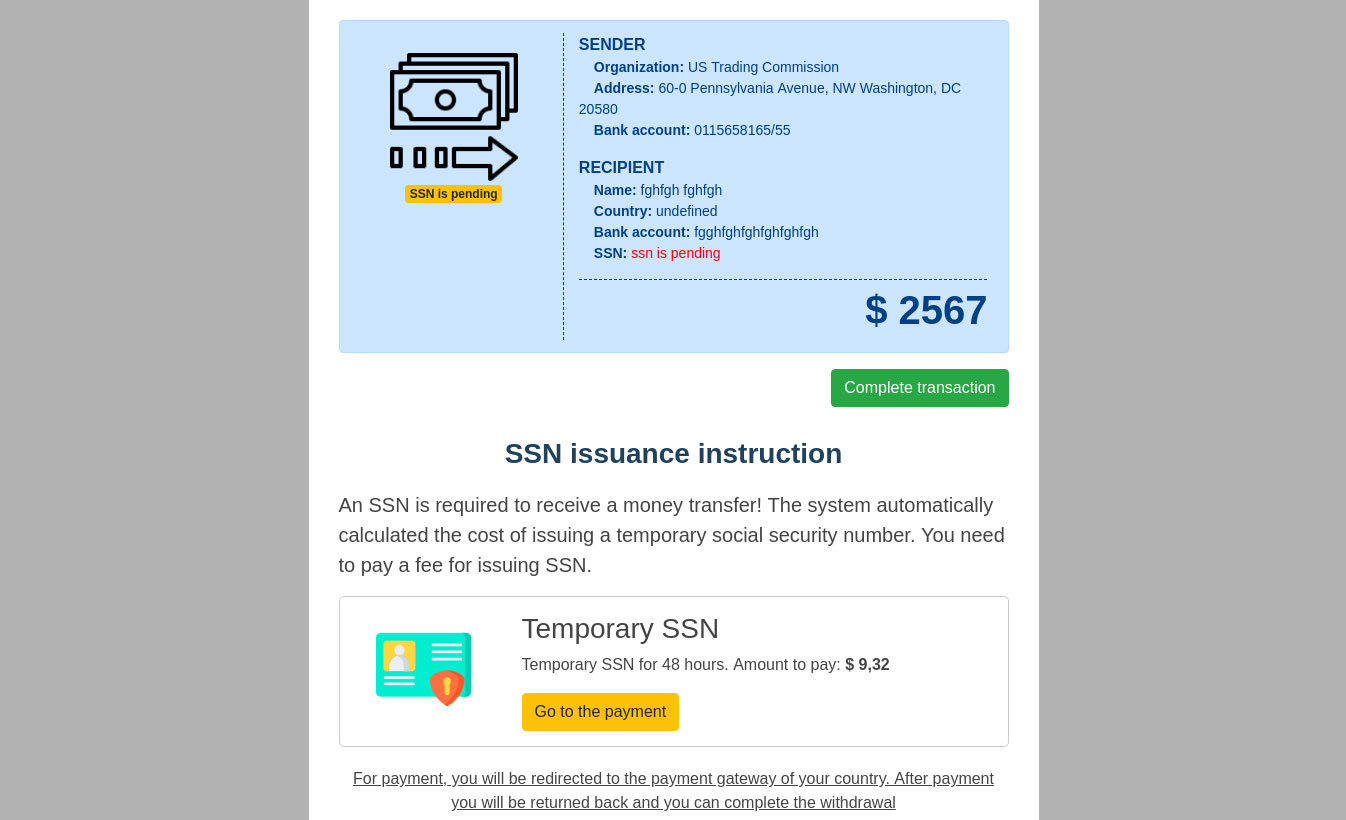

Recently, cybercriminals have exploited the theme of data leaks to try to defraud people. Data breaches, and the fines imposed for failing to safeguard data, are now a staple feature of the news. The scammers posed as an organization called the “Personal Data Protection Fund” and claim that the “US Trading Commission” had set up a fund to compensate people whose personal data had been exposed.

However, in order to get the compensation, the victims are asked to provide a social security number. The scammers offer to sell a temporary SSN to those who don’t have one.

Even if the potential victim enters a valid SSN, they are still directed to a page asking them to purchase a temporary SSN.

You can read the full story here.

… and coronavirus

The bigger the hook, the bigger the pool of potential victims. So it’s no surprise that cybercriminals are exploiting the COVID-19 pandemic. We have found malicious PDF, MP4 and DOCX files disguised as information about the coronavirus. The names of the files suggest they contain video instructions on how to protect yourself, updates on the threat and even virus detection procedures. In fact, these files are capable of destroying, blocking, modifying or copying data, as well as interfering with the operation of the computer.

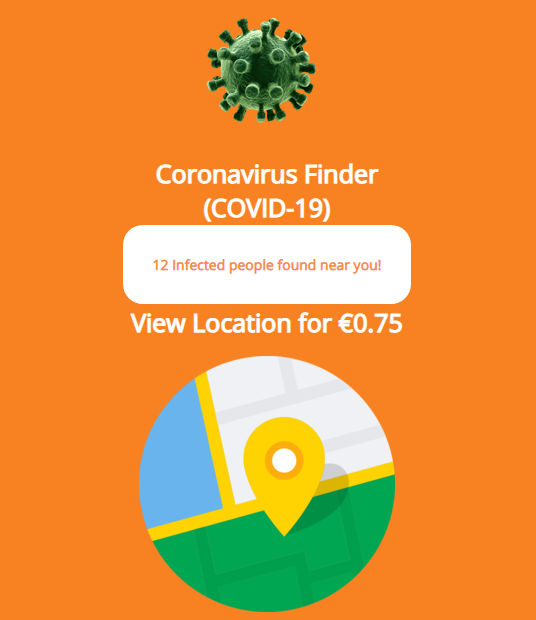

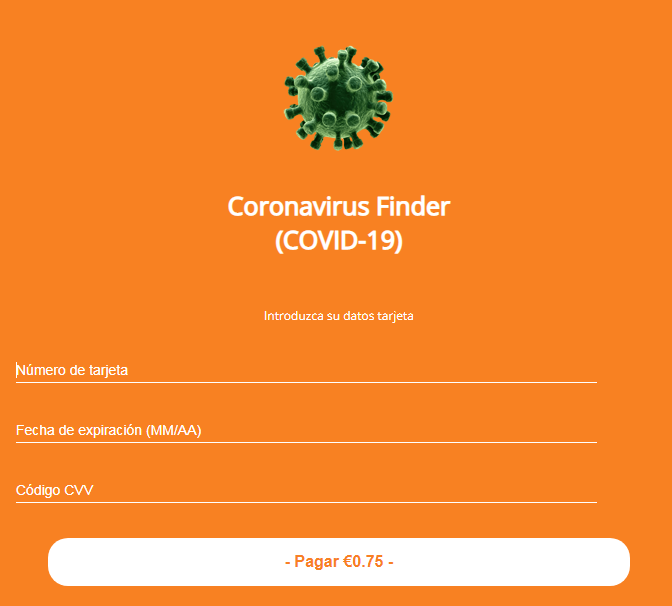

The cybercriminals behind the Ginp banking Trojan recently developed a new campaign related to COVID-19. After receiving a special command, the Trojan opens a web page called Coronavirus Finder. This provides a simple interface that claims to show the number of people nearby who are infected with the virus and asks you to pay a small sum to see their location.

The Trojan then provides a payment form.

Then … nothing else happens – apart from the criminals taking your money. Data from the Kaspersky Security Network suggests that most users who have encountered Ginp are located in Spain. However, this is a new version of Ginp that is tagged “flash-2”, while previous versions were tagged “flash-es12”. So perhaps the lack of “es” in the tag of the newer version means the cybercriminals are planning to expand their campaign beyond Spain.

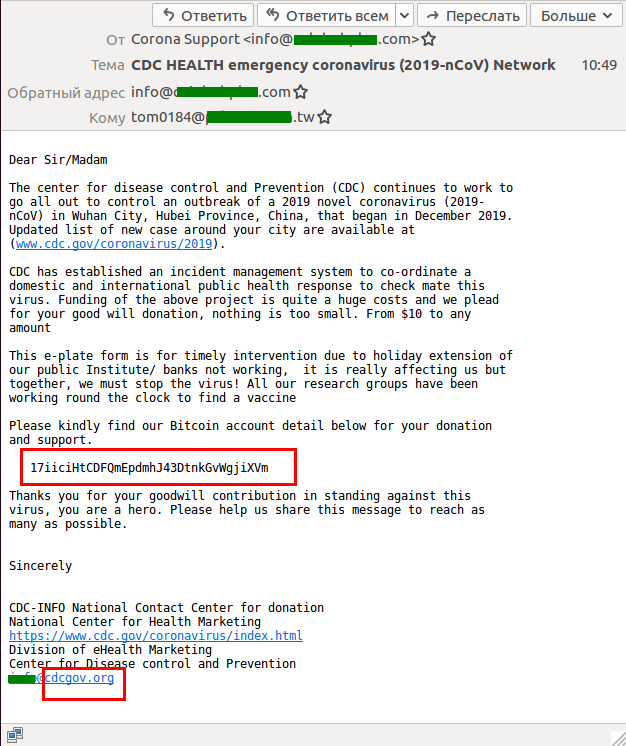

We have also seen a number of phishing scams where cybercriminals pose as bona fide organizations to trick people into clicking on links to fake sites where the scammers capture their personal information, or even ask them to donate money.

If you’ve ever wanted to know why it’s so easy for phishers to create spoof emails, and what efforts have been made to make it harder for them, you can find a good overview of the problems and potential solutions here.

Cybercriminals are also taking the opportunity to attack the information infrastructure of medical facilities, clearly hoping that the overload on IT services will provide them with an opportunity to break into hospital networks, or are attempting to extort money from clinical research companies. In an effort to ensure that IT security isn’t something that medical teams have to worry about, we’re offering medical institutions free six-month licenses for our core solutions.

AZORult campaign abuses popular VPN service to steal crypto-currency

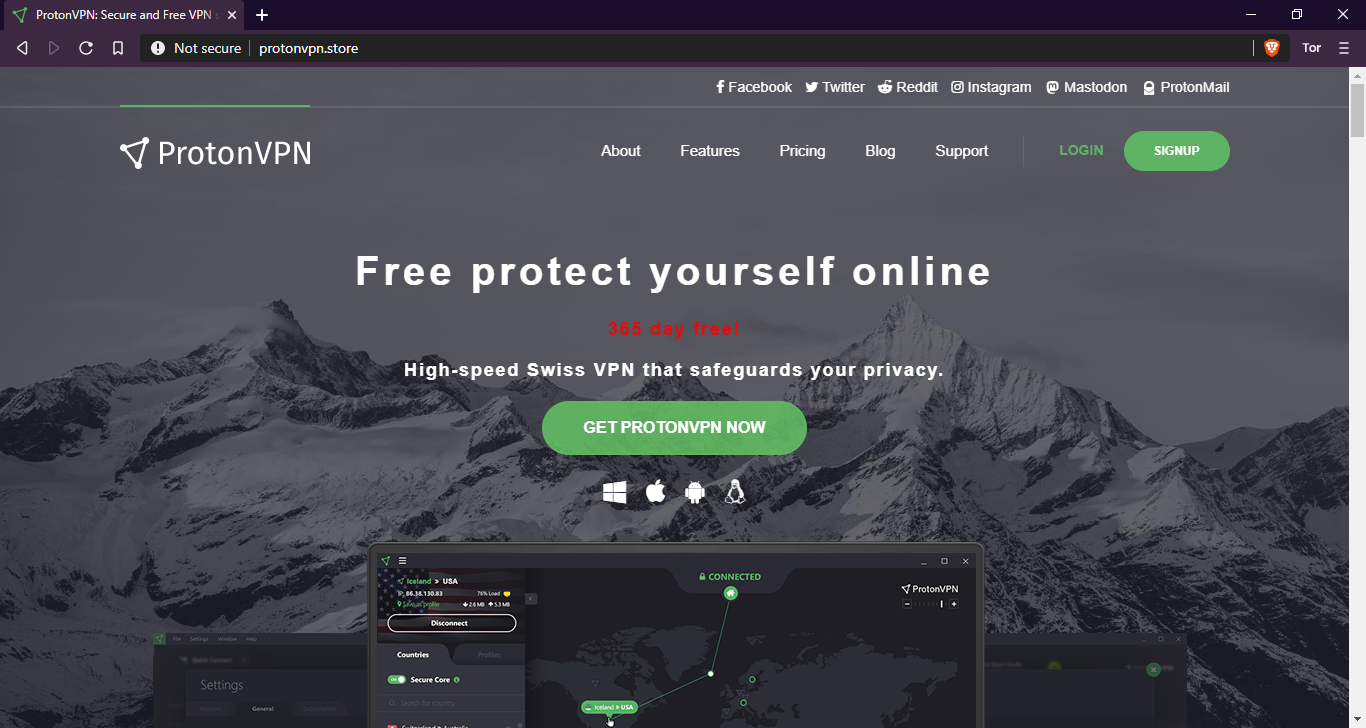

In February, we reported an unusual malware campaign in which cybercriminals were spreading the AZORult Trojan as a fake installer for ProtonVPN.

The aim of the campaign is to steal personal information and crypto-currency from the victims.

The attackers created a spoof copy a VPN service’s website, which looks like the original but has a different domain name. The criminals spread links to the domain through advertisements using different banner networks – a practice known as malvertizing. When someone visits a phishing website, they are prompted to download a free VPN installer for Windows. Once launched, this drops a copy of the AZORult botnet implant. This collects the infected device’s environment information and reports it to the server. Finally, the attackers steal crypto-currency from locally available wallets (Electrum, Bitcoin, Etherium and others), FTP logins, and passwords from FileZilla, email credentials, information from locally installed browsers (including cookies), credentials from WinSCP, Pidgin messenger and others.

AZORult is one of the most commonly bought and sold stealers on Russian forums due to its wide range of capabilities. The Trojan is able to harvest a good deal of data, including browser history, login credentials, cookies, files and crypto-wallet files; and can also be used as a loader to download other malware.

Distributing malware under the guise of security certificates

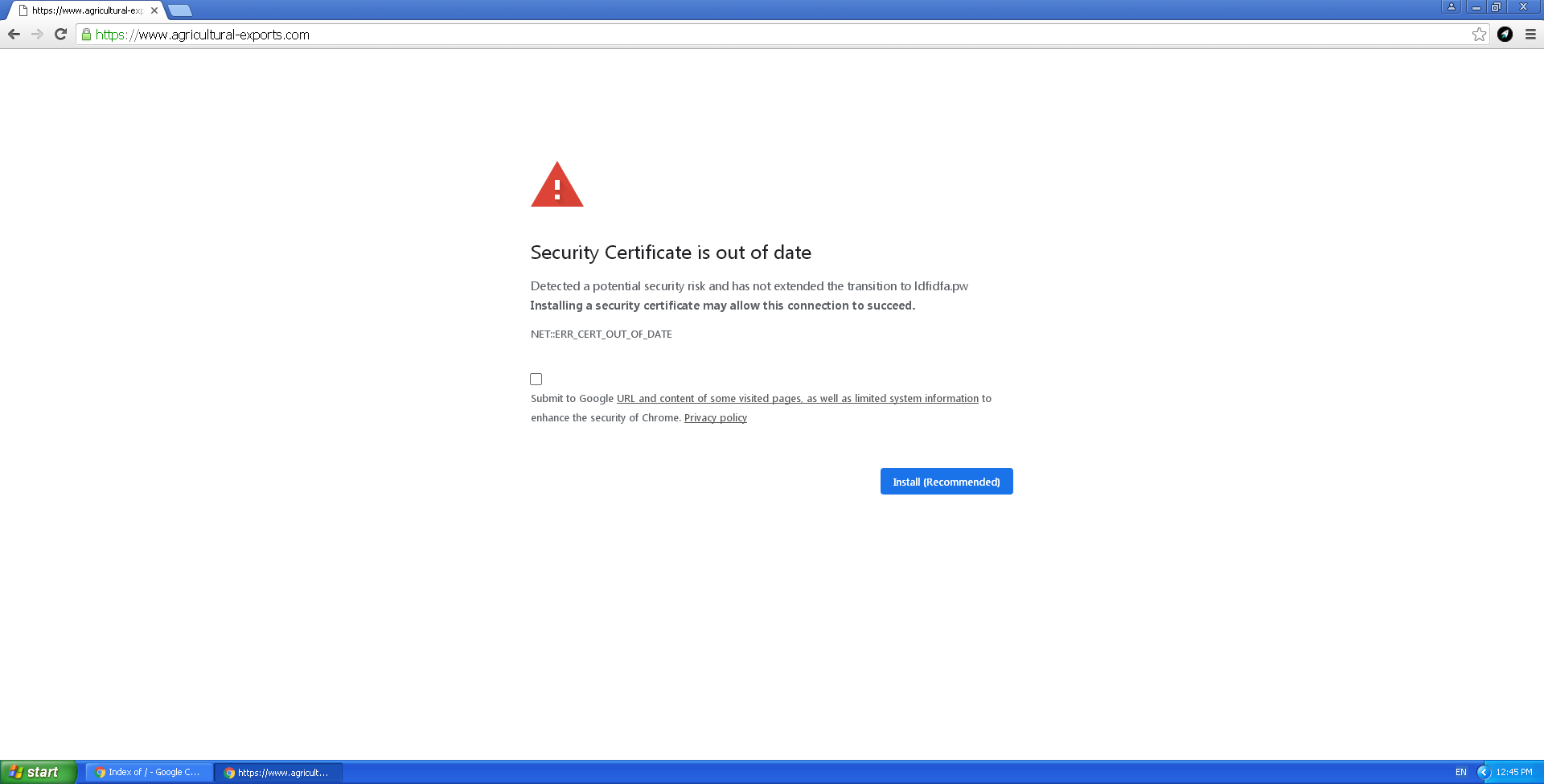

Distributing malware under the guise of legitimate software updates is not new. Typically, cybercriminals invite potential victims to install a new version of a browser or Adobe Flash Player. However, we recently discovered a new approach: visitors to infected sites were informed that some kind of security certificate had expired.

They were offered an update that infected them with malware – specifically the Buerak downloader and Mokes backdoor.

We detected the infection on variously themed websites – from a zoo to a store selling auto parts. The earliest infections that we found date back to January 16.

Mobile malware sending offensive messages

We have seen many mobile malware apps re-invent themselves, adding new layers of functionality over time. The Faketoken Trojan offers a good example of this. Over the last six years, it has developed from an app designed to capture one-time passcodes, to a fully-fledged mobile banking Trojan, to ransomware. By 2017, Faketoken was able to mimic many different apps, including mobile banking apps, e-wallets, taxi service apps and apps used to pay fines and penalties – all in order to steal bank account data.

Recently, we observed 5,000 Android smartphones infected by Faketoken sending offensive text messages. SMS capability is a standard feature of many mobile malware apps, many of which spread by sending links to their victims’ contacts; and banking Trojans typically try to make themselves the default SMS application, in order to intercept one-time passcodes. However, we had not seen one become a mass texting tool.

The messages sent by Faketoken are charged to the owner of the device; and since many of the infected smartphones we saw were texting a foreign number, the cost was quite high. Before sending any messages, the Trojan checks to see if there are sufficient funds in the victim’s bank account. If there are, Faketoken tops up the mobile account sending any messages.

We don’t yet know whether this is a one-off campaign or the start of a trend. To avoid becoming a victim of Faketoken, download apps only from Google Play, disable the downloading of apps from other sources, don’t follow links from messages and protect your device with a reputable mobile security product.

The use and abuse of the Android AccessibilityService

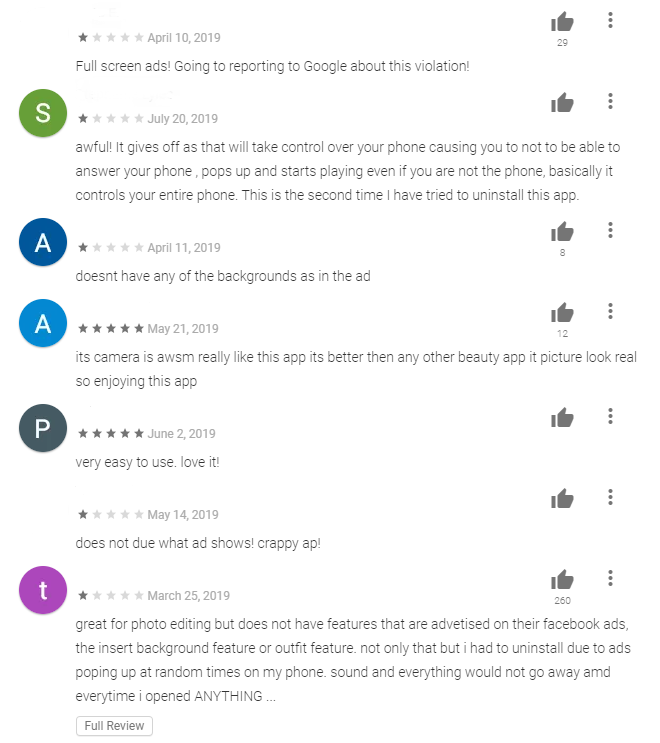

In January, we reported that cybercriminals were using malware to boost the rating of specific apps, to increase the number of installations.

The Shopper.a Trojan also displays advertising messages on infected devices, creates shortcuts to advertising sites and more.

The Trojan opens Google Play (or other app store), installs several programs and writes fake user reviews about them. To prevent the victim noticing, the Trojan conceals the installation window behind an ‘invisible’ window. Shopper.a gives itself the necessary permissions using the Android AccessibilityService. This service is intended to help people with disabilities use a smartphone, but if a malicious app obtains permission to use it, the malware has almost limitless possibilities for interacting with the system interface and apps – including intercepting data displayed on the screen, clicking buttons and emulating user gestures.

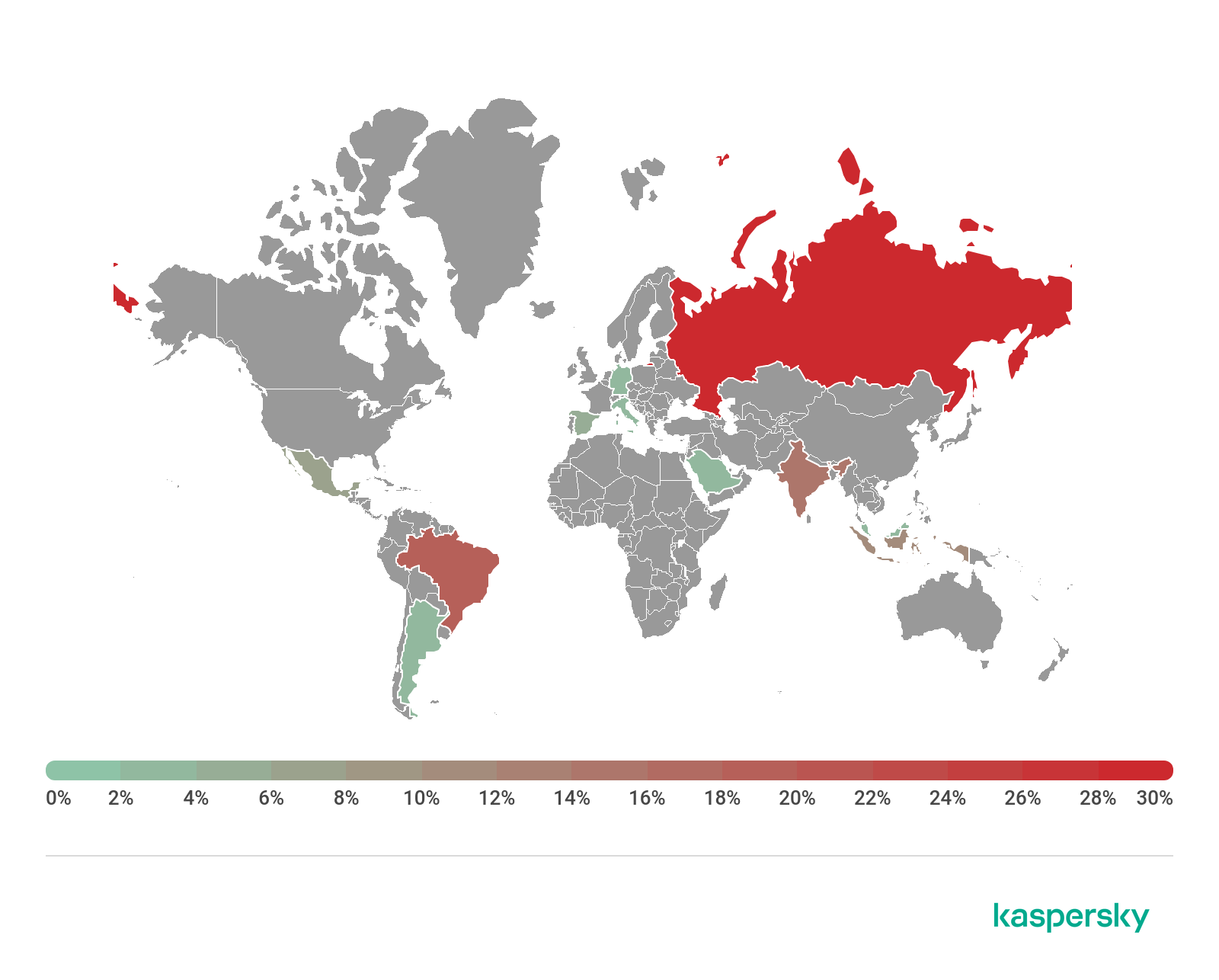

Shopper.a was most widespread in Russia, Brazil and India.

You should be wary if an app requests access to the AccessibilityService but doesn’t need it. Even if the only danger posed by such apps comes from automatically written reviews, there is no guarantee that its creators will not change the payload later.

Everyone loves cookies – including cybercriminals

We recently discovered a new malicious Android Trojan, dubbed Cookiethief, designed to acquire root permissions on the victim’s device and transfer cookies used by the browser and the Facebook app to the cybercriminals’ C2 server. Using the stolen cookies, the criminals can gain access to the unique session IDs that websites and online services use to identify someone, thereby allowing the criminals to assume someone’s identity and gain access to online accounts without the need for a login and password.

On the C2 server, we found a page advertising services for distributing spam on social networks and messengers, which we think is the underlying motive in stealing cookies.

From the C2 server addresses and encryption keys used, we were able to link Cookiethief to widespread Trojans such as Sivu, Triada, and Ztorg. Usually, such malware is either planted in the device firmware before purchase, or it gets into system folders through vulnerabilities in the operating system and then downloads various applications onto the system.

Stalkerware: no place to hide

We recently discovered a new sample of stalkerware – commercial software typically used by those who want to monitor a partner, colleague or others – that contains functionality beyond anything we have seen before. You can find more information on stalkerware here and here.

MonitorMinor, goes beyond other stalkerware programs. Primitive stalkerware uses geo-fencing technology, enabling the operator to track the victim’s location, and in most cases intercept SMS and call data. MonitorMinor goes a few steps further: recognizing the importance of messengers as a means of data collection, this app aims to get access to data from all the popular modern communication tools.

Normally, the Android sandbox prevents direct communication between apps. However, if a superuser app has been installed, which grants root access to the system, it overrides the security mechanisms of the device. The developers of MonitorMinor use this to enable full access to data on a variety of popular social media and messaging applications, including Hangouts, Instagram, Skype and Snapchat. They also use root privileges to access screen unlock patterns, enabling the stalkerware operator to unlock the device when it is nearby or when they next have physical access to the device. Kaspersky has not previously seen this feature in any other mobile threat.

Even without root access, the stalkerware can operate effectively by abusing the AccessibilityService API, which is designed to make devices friendly for users with disabilities. Using this API, the stalkerware is able to intercept any events in the applications and broadcast live audio.

Our telemetry indicates that the countries with the largest share of installations of MonitorMinor are India, Mexico, Germany, Saudi Arabia and the UK.

We recommend the following tips to reduce the risk of falling victim to a stalker:

- Block the installation of apps from unknown sources in your smartphone settings.

- Never disclose the password or passcode to your mobile device, even with someone you trust.

- If you are ending a relationship, change security settings on your mobile device, such as passwords and app location access settings.

- Keep a check on the apps installed on your device, to see if any suspicious apps have been installed without your consent

- Use a reliable security solution that notifies you about the presence of commercial spyware programs aimed at invading your privacy, such as Kaspersky Internet Security.

- If you think you are being stalked, reach out to a professional organization for advice.

- For further guidance, contact the Coalition against Stalkerware

- There are resources that can assist victims of domestic violence, dating violence, stalking and sexual violence. If you need further help, please contact the Coalition against Stalkerware.

IT threat evolution Q1 2020

Stephine Busboom

I agree with you