In this article, I want to demonstrate extracting the firmware from a secure USB device running on the Cortex M0.

Who hacks video game consoles?

The manufacture of counterfeit and unlicensed products is widespread in the world of video game consoles. It’s a multi-billion dollar industry in which demand creates supply. You can now find devices for almost all the existing consoles that allow you to play copies of licensed video game ‘backups’ from flash drives, counterfeit gamepads and accessories, various adapters, some of which give you an advantage over other players, and devices for the use of cheats in online and offline video games. There are even services that let you buy video game achievements without having to spend hours playing. Of course, this is all sold without the consent of the video game console manufacturers.

Modern video game consoles, just like 20 years ago, are proprietary systems where the rules are set by the hardware manufacturers, and not by the millions of customers using those devices. A variety of protective measures are included in their design to ensure these consoles only run signed code, so they only play licensed and legally acquired video games and all players have equal rights and only play with officially licensed accessories. In some countries it’s even illegal to try and hack your own video game console.

But at the same time the very scale of the protection makes these consoles an attractive target and one big ‘crackme’ for enthusiasts interested in information security and reverse engineering. The more difficult the puzzle, the more interesting it is to solve. Especially if you’ve grown up with a love for video games.

Protection scheme of DualShock 4

Readers who follow my twitter account may know that I’m a long-time fan of reverse engineering video game consoles and everything related to them, including unofficial game devices. In the early days of PlayStation 4, a publicly known vulnerability in the FreeBSD kernel (which PlayStation 4 is based on) let me and many other researchers take a look at the architecture and inner workings of the new game console from Sony. I carried out a lot different research, some of which included looking at how USB authentication works in PlayStation 4 and how it distinguishes licensed devices and blocks unauthorized devices. This subject was of interest because I had previously done similar research on other consoles. PlayStation 4’s authentication scheme turned out to be much simpler than that used in Xbox 360, but no less effective.

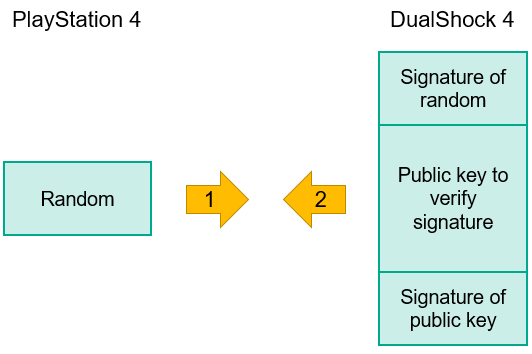

PS4 sends 0x100 random bytes to DualShock 4 and in response the gamepad creates an RSASSA-PSS SHA-256 signature and sends it back among the cryptographic constants N and E (public key) needed to verify it. These constants are unique for all manufactured DualShock 4 gamepads. The gamepad also sends a signature needed for verification of N and E. It uses the same RSASSA-PSS SHA-256 algorithm, but the cryptographic constants are equal for all PlayStation 4 consoles and are stored in the kernel.

This means that if you want to authenticate your own USB device, it’s not enough to hack the PlayStation 4 kernel – you need the private key stored inside the gamepad. And even if someone manages to hack a gamepad and obtains the private key, Sony can still denylist the key with a firmware update. If after eight minutes a game console has not received an authentication response it stops communication with the gamepad and you need to remove it from the USB port and plug it in again to get it to work. That’s how the early counterfeit gamepads worked by simulating a USB port unplug/plug process every eight minutes, and it was very annoying for anyone who bought them.

Rumors of super counterfeit DualShock 4

There were no signs of anyone hacking this authentication scheme for quite some time until I heard rumors about new fake gamepads on the market that looked and worked just like the original. I really wanted to take a look at them, so I ordered a few from Chinese stores.

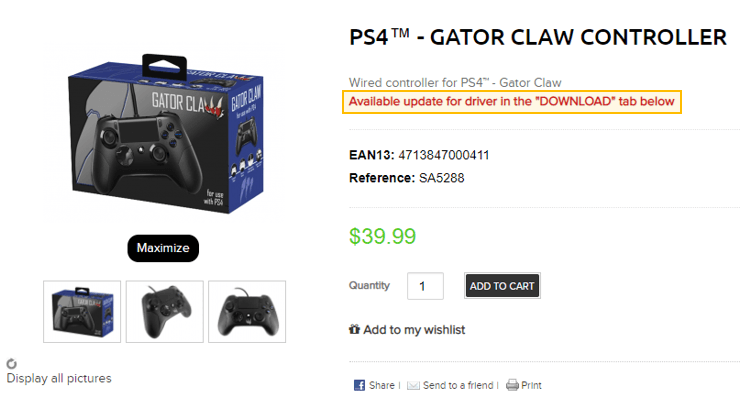

While I was waiting for my parcels to arrive, I decided to try and gather more information about counterfeit gamepads. After quite a few search requests I found a gamepad known as Gator Claw.

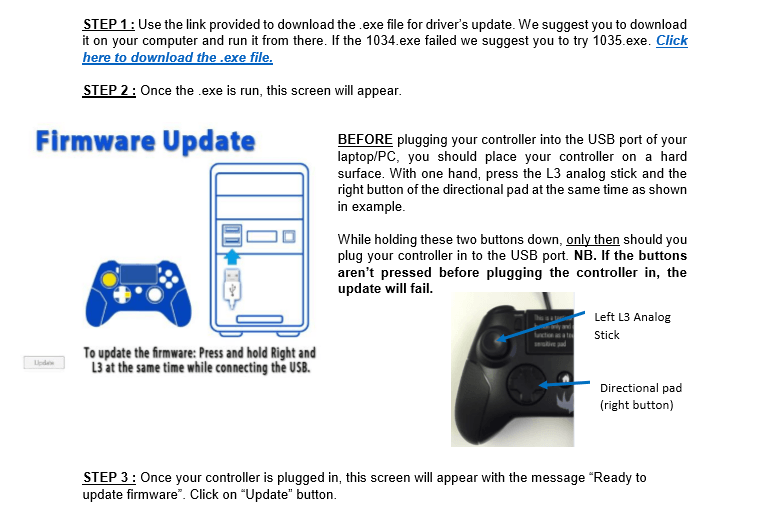

There was an interesting discussion on Reddit where people were saying that it worked just like other unauthorized gamepads but only for eight minutes, but that the developers had managed to fix this with a firmware update. The store included a link to the firmware update and a manual.

Basics of embedded firmware analysis

The first thing I did was to take a look at the resource section of the firmware updater executable.

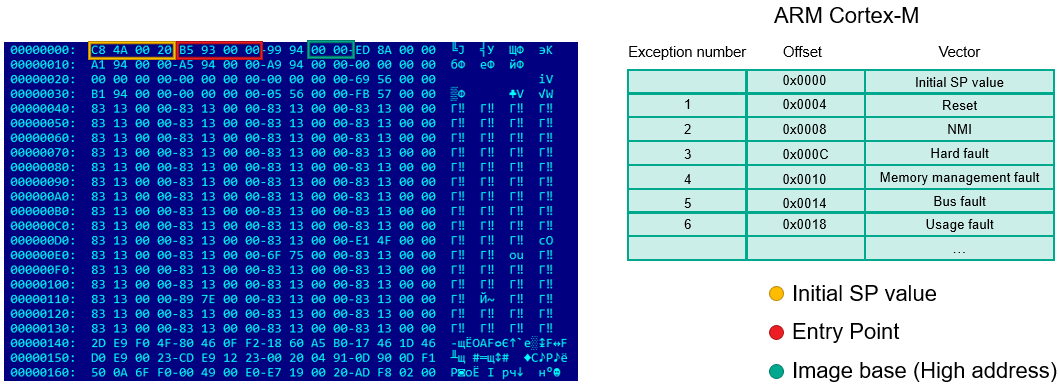

Readers who are familiar with writing code for embedded devices will most likely recognize this file format. This is an Intel HEX file format which is commonly used for programming microcontrollers, and many compilers (for example GNU Compiler) may output compiled code in this format. Also, we can see that the beginning of the firmware doesn’t have high entropy and sequences of bytes are easily recognizable. That means the firmware is not encrypted or compressed. After decoding the firmware from Intel HEX format and loading in hex editor (010 Editor is able to open files directly in that format) we are able to take a look at it. What architecture is it compiled for? ARM Cortex-M is so widely adopted that I recognize it straight away.

According to the specifications, the first double word is the initial stack pointer and after that comes the table of exception vectors. The first double word in this table is Reset vector that is used as the firmware entry point. The high addresses of other exception handlers give an idea of the firmware’s base address.

Besides firmware, the resource section of the firmware updater also contained a configuration file with a description of different microcontrollers. The developers of the firmware updater most probably used publicly available source code from the manufacturers of microcontrollers, which would explain why this configuration file came with source code.

After searching the microcontroller identificators from the config file, we found the site of the manufacturer – Nuvoton. Product information among technical documentation and the SDK is freely available for download without any license agreements.

At this point we have the firmware, we know its architecture and microcontroller manufacturer, and we have information about the base address, initial stack pointer and entry point. We have more information than we actually need to load the firmware in IDA Pro and start analyzing it.

ARM processors have two different instruction sets: ARM (32 bit instructions) and Thumb (16-bit instructions extended with Thumb-2 32-bit instructions). Cortex-M0 supports only Thumb mode so we will switch the radio button in “Processor options – Edit ARM architecture options – Set ARM instructions” to “NO” when loading the firmware in IDA Pro.

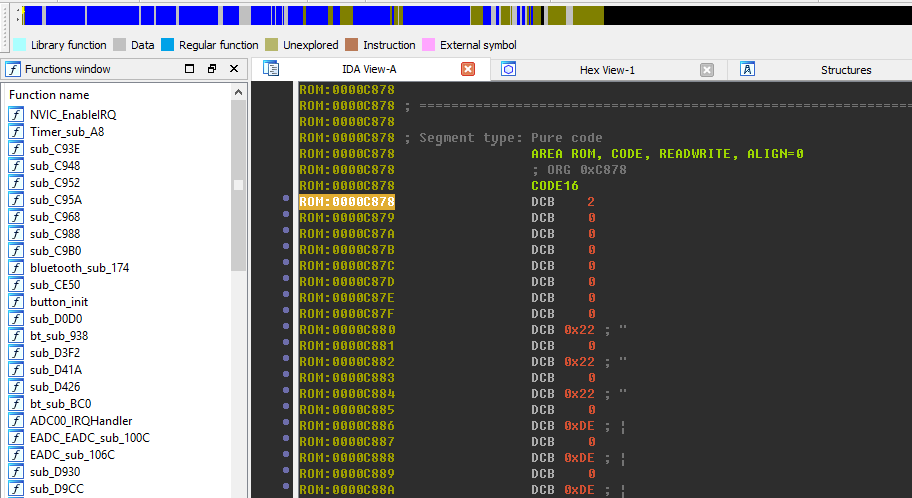

After that we can see the firmware has loaded at base address 0 and automatic analysis has recognized almost every function. The question now is how to move forward with the reverse engineering of the firmware?

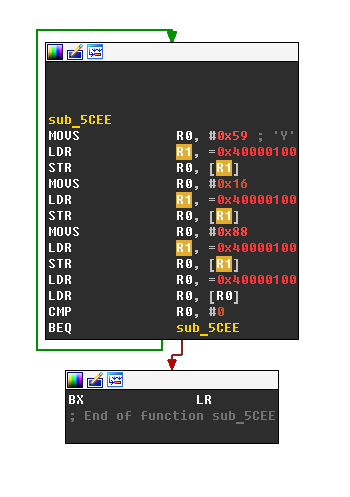

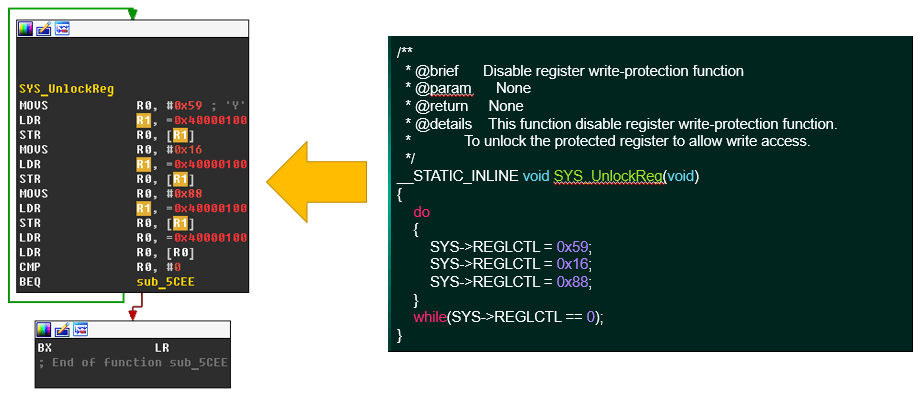

If we analyze the firmware, we’ll see that throughout it performs read and write operations to memory with the base address 0x40000000. This is the base address of memory mapped input output (MMIO) registers. These MMIO registers allow you to access and control all the microcontroller’s peripheral components. Everything that the firmware does happens through access to them.

By searching through the technical documentation for the address 0x40000000 we find that this microcontroller belongs to the M451 family. Now that we know the family of the microcontroller, we are able to download the SDK and code samples for this platform. In the SDK we find a header file with a definition of all MMIO addresses, bit fields and structures. We can also compile code samples with all the libraries and compare them with functions in our IDB, or we can look for the names of the MMIO addresses in the source code and compare it with our disassembly. This makes the process of reverse engineering straightforward. That’s because we know the architecture and model of the microcontroller and we have a definition of all MMIO registers. Analysis would be much more complicated if we didn’t have this information. It’s fair to say that is why many vendors only distribute the SDK after an NDA is signed.

In the shadow of colossus

I analyzed Gator Claw’s firmware while waiting for my fake gamepad to arrive. There wasn’t much of interest inside – authentication data is sent to another microcontroller accessible over I2C and the response is sent back to the console. The developers of this unlicensed gamepad knew that this firmware may be reverse engineered and the existence of more counterfeit gamepads may hurt their business. To prevent this, another microcontroller was used for the sole purpose of keeping secrets safe. And this is common practice. The hackers put a lot of effort into their product and don’t want to be hacked too. What really caught my attention in this firmware was the presence of some seemingly unused string. Most likely it was meant to be part of a USB Device Descriptor but that particular descriptor was left unused. Was this string left on purpose? Is it some kind of signature? Quite probably, because this string is the name of a major hardware manufacturer best known for their logic analyzers. But it also turns out they have a gaming division that aims to be an original equipment manufacturer (OEM) and even has a number of patents related to the production of gaming accessories. Besides that, they also have subsidiary and their site has huge assortment of gaming accessories sold under a single brand. Among the products on sale are two dozen adapters that allow the gamepads of one console to be used with another console. For example, there’s one product that lets you connect the gamepad of an Xbox 360 to PlayStation 4, another product that lets you connect a PlayStation 3 gamepad to Xbox One, and so on, including a universal ‘all in one’. The list of products also includes adapters that allow you to connect a PC mouse and keyboard to the PS4, Xbox One and Nintendo Switch video game consoles, various gamepads and printed circuit boards to create your own arcade controllers for gaming consoles. All the products come with firmware updaters similar to the one that was provided for Gator Claw, but with one notable difference – all the firmware is encrypted.

The printed circuit boards for creating your own arcade controllers let you take a look at PCB design without buying a device and taking it apart. Their design is most likely very close to that of Gator Claw. We can see two microcontrollers; one of them should be Nuvoton M451 and the other is an additional microcontroller to store secrets. All traces go to the microcontroller under black epoxy, so it should be the main microcontroller, and the microcontroller with the four yellow pins seems to have what’s required to work over I2C.

Revelations

By this time I had finally received my parcel from Shenzhen and this is what I found inside. I think you’ll agree that the counterfeit gamepad looks exactly like the original DualShock 4. And it feels like it too. It’s a wireless gamepad made with good quality materials and has a working touch pad, speaker and headset port.

I pressed one of the combinations found in the update instructions and powered it on. The gamepad booted into DFU mode! After connecting the gamepad to a PC in this mode it was recognized as another device with different identifiers and characteristics. I already knew what I was going to see inside…

I soldered a few wires to what looked like JTAG points and connected it to a JTAG programmer. The programming tool recognized the microcontroller, but a Security Lock was set.

Hacking microcontroller firmware through a USB

After this rather lengthy introduction, it’s now time to return to the main subject of this article. USB (Universal Serial Bus) is an industry standard for peripheral devices. It’s designed to be very flexible and allow a wide range of applications. USB protocol defines two entities – one host to whcih other devices connect. USB devices are divided into classes such as hub, human interface, printer, imaging, mass storage device and others.

Data and control exchange between the devices with the host happens through a set of uni-directional or bi-directional pipes. By pipes we consider data transfers between host software and a particular endpoint on a USB device. One device may have many different endpoints to exchange different types of data.

There are four different types of data transfers:

- Control Transfers (used to configure a device)

- Bulk Data Transfers (generated or consumed in relatively large and bursty quantities)

- Interrupt Data Transfers (used for timely but reliable delivery of data)

- Isochronous Data Transfers (occupy a prenegotiated amount of USB bandwidth with a prenegotiated delivery latency)

All USB devices must support a specially designated pipe at endpoint zero to which the USB device’s control pipe will be attached.

Those types of data transfers are implemented with the use of packets provided according to the scheme below.

In fact, USB protocol is a state machine and in this article we are not going to examine all those packets. Below you can see an example of the packets used in a Control Transfer.

USB devices may contain vulnerabilities when implementing Bulk Transfers, Interrupt Transfers, Isochronous Transfers, but those types of data transfers are optional and their presence and usage will vary from target to target. But all USB devices support Control Transfers. Their format is common and this makes this type of data transfer the most attractive to analyze for vulnerabilities.

The scheme below shows the format of the SETUP packet used to perform a Control Transfer.

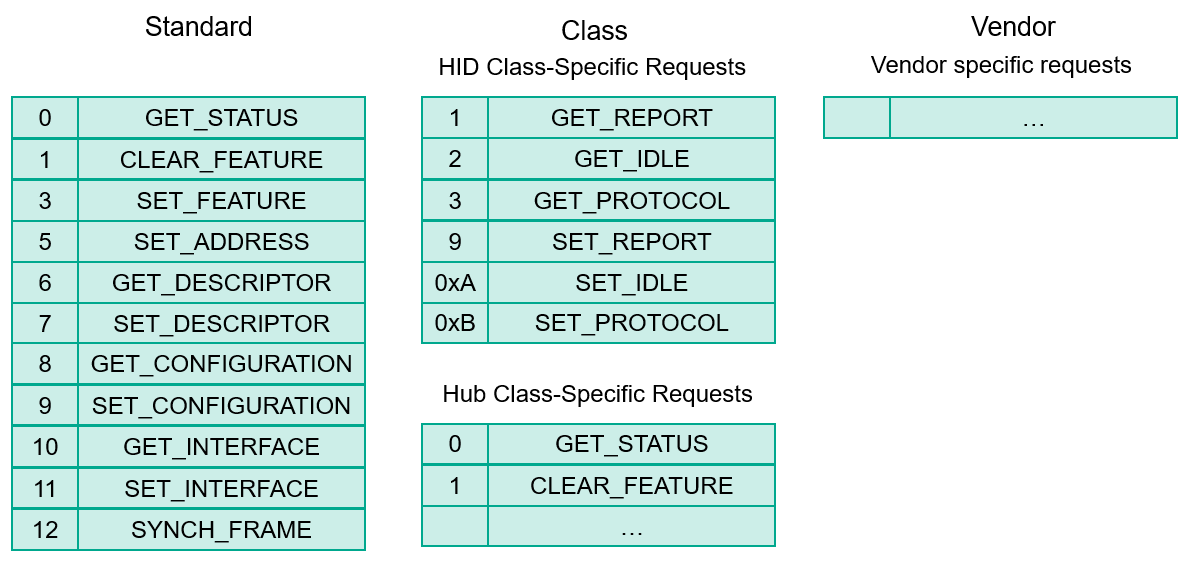

The SETUP packet occupies 8 bytes and it can be used to obtain different types of data depending on the type of request. Some requests are common for all devices (for example GET DESCRIPTOR); others depend on the class of device and manufacturer permission. The length of data to send or receive is a 16-bit word provided in the SETUP packet.

Summing up: Control Transfers use a very simple protocol that’s supported by all USB devices. It can have lots of additional requests and we can control the size of data. All of that makes Control Transfers a perfect target for fuzzing and glitching.

Exploitation

To hack my counterfeit gamepad I didn’t have to fuzz it because I found vulnerabilities while I was looking at the Gator Claw code.

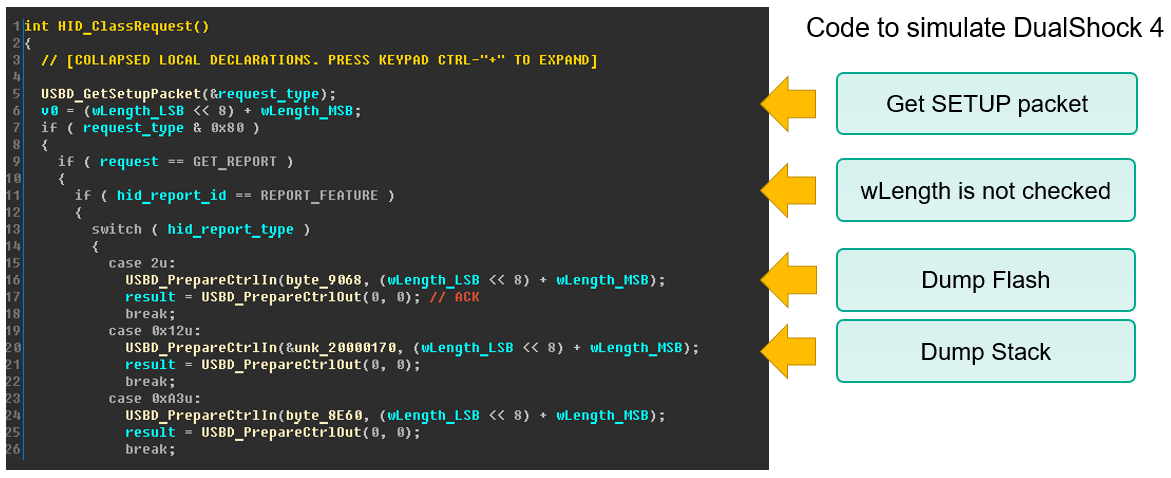

Function HID_ClassRequest() is present to emulate the work of the original DualShock 4 gamepad and implements the bare minimum of required requests to get it working with PlayStation 4. USBD_GetSetupPacket() gets the SETUP packet and depending on the type of report it will either send data with the function USBD_PrepareCntrlIn() or will receive with the function USBD_PrepareCntrlOut(). This function doesn’t check the length of the requested data and this should allow us to read part of the internal Flash memory where the firmware is located and also read and write to the beginning of SRAM memory.

The size of the DATA packet is defined in the USB Device Descriptor (also received with the Control Transfer), but what seems to be left unnoticed is the fact that this size defines the length of a single packet and there may be lots of packets depending on the length set in the SETUP packet.

It is noteworthy that the code samples provided on the site of Nuvoton also don’t have checks for length and it could lead to the spread of similar bugs in all products that used this code as a reference.

SRAM (static random access memory) is a memory that among other things is occupied by stack. SRAM is often also executable memory (this is configurable). This is usually done to increase performance by making firmware copy pieces of code that are often called (for example, Real-Time Operating System) to SRAM. There is no guarantee that the top of the stack will be reachable by buffer overflow, but the chances of that are nevertheless high.

Surprisingly, the main obstacle to exploiting USB firmware is the operating system. The following was observed while I was working with Windows, but I think most of it also applies to Linux without special patches.

First of all, the operating system doesn’t let you read more than 4 kb during a Control Transfer. Secondly, in my experience the operating system doesn’t let you write more than a single DATA packet during a Control Transfer. Thirdly, the USB device may have hidden requests and all attempts to use them will be blocked by the OS.

This is easy to demonstrate with human interface devices (HID), including gamepads. HIDs come with additional descriptors (HID Descriptor, Report Descriptor, Physical Descriptor). A Report Descriptor is quite different from the other descriptors and consists of different items that describe supported reports. If a report is missing from Report Descriptor, then the OS will refuse to complete it, even if it’s handled in the device. This basically detracts from the discovery and exploitation of vulnerabilities in the firmware of USB devices and those nuances most probably prevented the discovery of vulnerabilities in the past.

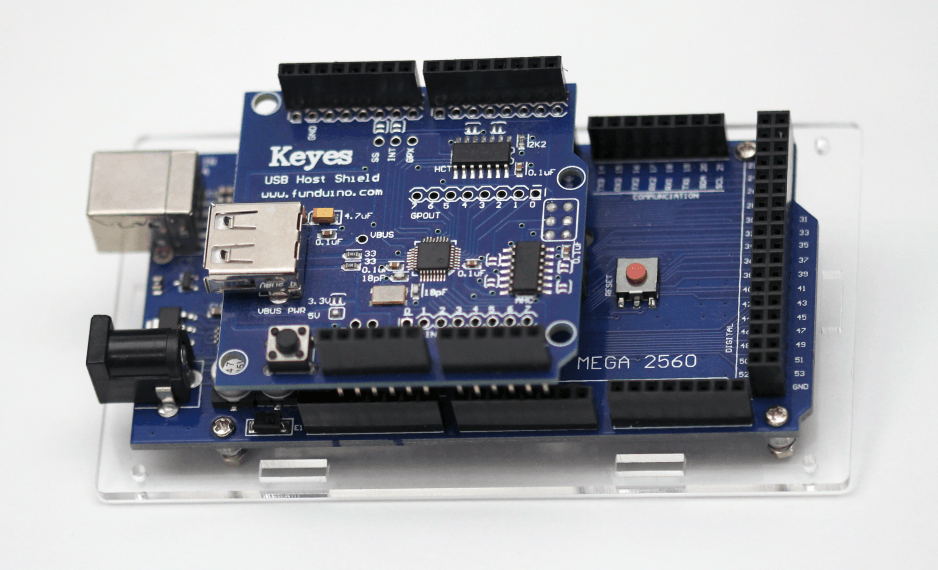

To solve this problem without having to read and recompile the sources of the Linux kernel, I just used low end instruments that I had available at hand: Arduino Mega board and USB Host Shield (total < $30).

After connecting devices with the above scheme, I used the Arduino board to perform a Control Transfer without any interference from the operating system.

The counterfeit gamepad had the same vulnerabilities as Gator Claw and the first thing I did was to dump part of the firmware.

The easiest way to find the base address of the firmware dump is to find a structure with pointers to known data. After that we can calculate the delta of addresses and load a partial dump of the firmware to IDA Pro.

The firmware dump allowed us to find out the address of the printf() function that outputs the information in UART required for factory quality assurance. More than that, I was able to find the hexdump() function in the dump, meaning I didn’t even need to write shellcode.

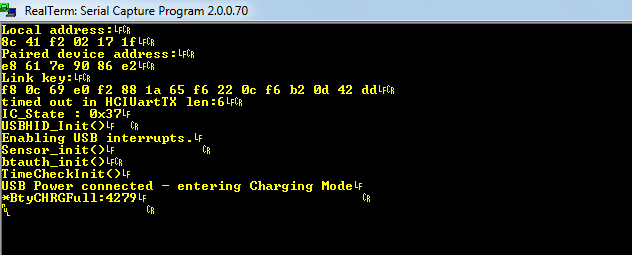

After locating the UART points on the printed circuit board of the gamepad, soldering wires and connecting them to a TTL2USB adapter, we can see the output in a serial terminal.

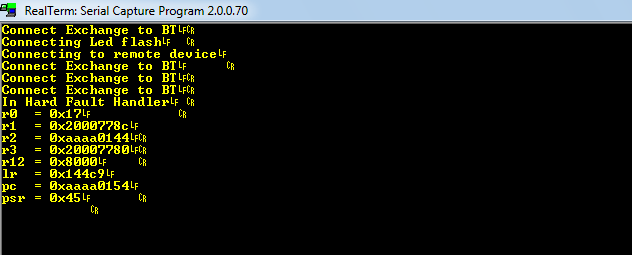

A standard library for Nuvoton microcontrollers comes with a very handy handler of Hard Fault exceptions that outputs a register dump. This greatly facilitates in exploitation and allows exploits to be debugged.

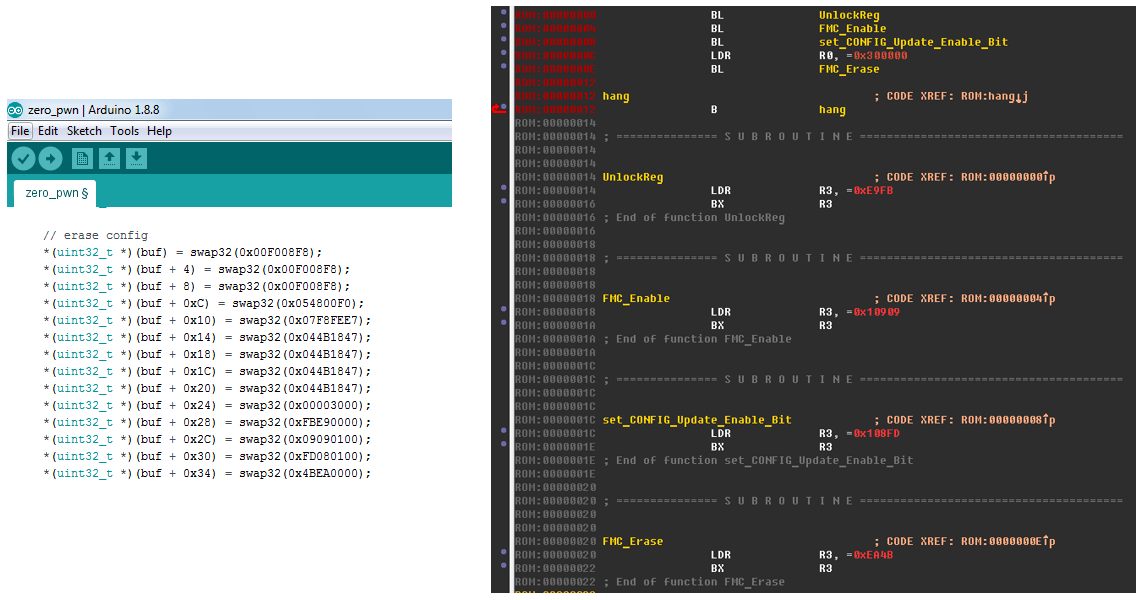

A final exploit to dump firmware can be seen in the screenshot below.

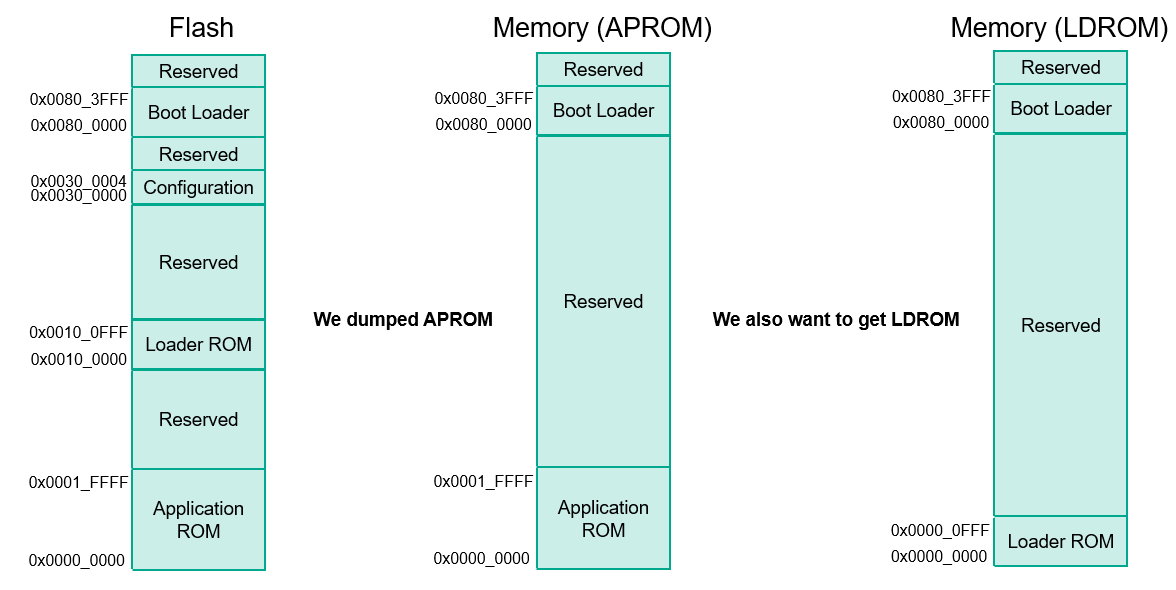

But this way to dump firmware is not perfect because the microcontrollers of the Nuvoton M451 family may have two different types of firmware – main firmware (APROM) and mini-firmware for device firmware update (LDROM).

APROM and LDROM are mapped at the same memory addresses and because of that it’s only possible to dump one of them. To get a dump of LDROM firmware we need to disable the security lock and read the flash memory with a programming tool.

Crypto fail

Analysis of the firmware responsible for updates (LDROM) revealed that it’s mostly standard code from Nuvoton, but with added code to decrypt firmware updates.

The cryptographic algorithm used for decrypting firmware updates is a custom block cipher. It is performed in cipher block chaining mode, but the block size is just 32 bits. This algorithm takes a key that is a textual (ascii) identificator of the product and array of instructions that define what transformation should be performed on the current block. After encountering the end of the key and array their current position is set to the initial position. The list of transformations includes six operations: xor, subtraction, subtraction (reverse), and the same operations but with the bytes swapped. Because the firmware contains large areas filled with zeroes, it makes it easy to calculate the secret parts of this algorithm.

Applying the algorithm extracted from the firmware of the counterfeit gamepad to all the firmware of the accessories found on the site of a major OEM manufacturer revealed that all of them use this encryption algorithm, and the weaknesses in this algorithm allowed us to calculate the encryption keys for all devices and decrypt their firmware updates. In other words, the algorithm used inside the counterfeit product led to the security of all the products developed by that manufacturer being compromised.

Conclusion

This blog post turned out to be quite long, but I really wanted to prepare it for a very wide audience. I have given a step-by-step guide on the analysis of embedded firmware, finding vulnerabilities and exploiting them to acquire a firmware dump and to carry out code execution on a USB device.

The subject of glitching attacks is not included in the scope of this article, but such attacks are also very effective against USB devices. For those who want to learn more about them, I recommend watching this video. For those wondering how pirates managed to acquire the algorithm and key from DualShock 4 to make their own devices, I suggest reading this article.

As for the mystery of the auxiliary microcontroller that was used to keep secrets, I found out that it was not used in all devices and was only added for obscurity. This microcontroller doesn’t keep any secrets and is only used for SHA1 and SHA256. This research also aids enthusiasts to create their own open source projects for use with game consoles.

As for buyers of counterfeit gamepads, they are not in an enviable position because manufacturers block illegally used keys and the users end up without a working gamepad or hints on where to get firmware updates.

Hacking microcontroller firmware through a USB

Martin Rakhmanov

Good research! Small note: you give a link to https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=CVE-2014-9322 saying it’s a FreeBSD bug. Isn’t it about some Linux kernel issue?