Not so long ago, Kaspersky clients in the United States approached Kaspersky researchers with a request to investigate a new type of malicious software that they were able to recover from their organizations’ servers. The malware calls itself Grabit and is distinctive because of its versatile behavior. Every sample we found was different in size and activity from the others but the internal name and other identifiers were disturbingly similar. The timestamp seems valid and close to the documented infection timeline. Our documentation points to a campaign that started somewhere in late February 2015 and ended in mid-March. As the development phase supposedly ended, malware started spreading from India, the United States and Israel to other countries around the globe.

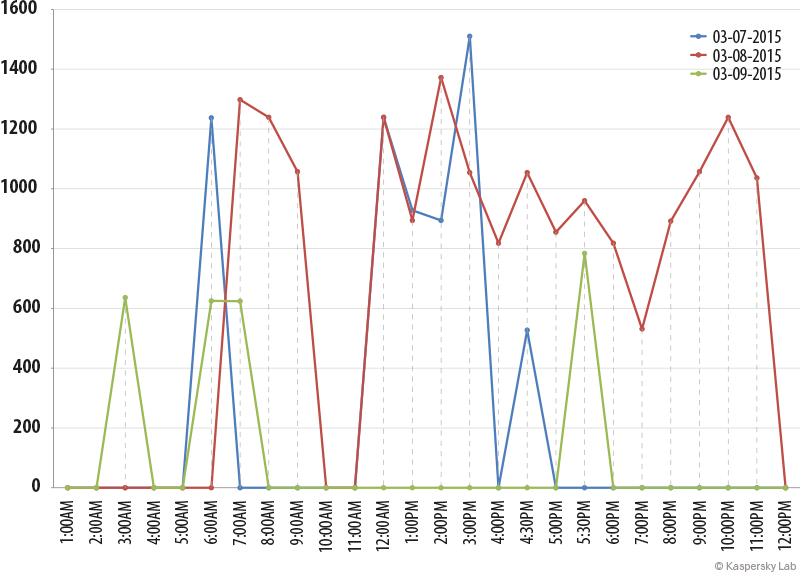

All of the dozens of samples we managed to collect were programmed in Windows machine 32bit processor, over the Microsoft .NET Framework (Visual Basic/C#). Files were compiled over the course of three days, between March 7th and 9th of 2015. The following chart illustrates how the group or individual created the samples, the size of each sample, the time of the day when each was compiled and the time lapses between each compilation.

Malware compilation timeline

The smallest sample (0.52Mb) and the largest (1.57Mb) were both created on the same day, which could indicate experiments made by the group to test features, packers and “dead code” implementations.

Looking at the chart, it is interesting to see the modus operandi as the threat actor consistently strives to achieve a variety of samples, different code sizes and supposedly more complicated obfuscation.

Along with these different sizes, activities and obfuscation, a serious encryption algorithm was also implemented in each one of them. The proprietary obfuscated string, methods and classes made it rather challenging to analyze. ASLR is also enabled, which might point to an open source RAT or even a commercial framework that packed the malicious software in a well written structure. This type of work is known as a mitigation factor for threat actors to keep their code hidden from analysts’ eyes.

During our research, dynamic analysis showed that the malicious software’s “call home” functionality communicates over obvious channels and does not go the extra mile to hide its activity. In addition, the files themselves were not programmed to make any kind of registry maneuvers that would hide them from Windows Explorer. Taking that into an equation, it seems that the threat actors are sending a “weak knight in a heavy armor” to war. It means that whoever programmed the malware did not write all the code from scratch. A well trained knight would never go to war with a blazing shield and yet a stick for a sword.

Looking into the “call home” traffic, the Keylogger functionality prepares files that act as a container for keyboard interrupts, collecting hostnames, application names, usernames and passwords. However, the interesting part lies here.

The file names contain a very informative string:

HawkEye_Keylogger_Execution_Confirmed_<VICTIM> 3.10.2015 6:08:31 PM

HawkEye is a commercial tool that has been in development for a few years now; it appeared in 2014, as a website called HawkEyeProducts, and made a very famous contribution to the hacker community.

In the website, the product shows great versatility as it contains many types of RATs, features and functionality, such as the traditional HawkEye Logger or other types of remote administration tools like Cyborg Logger, CyberGate, DarkComet, NanoCore and more. It seems to support three types of delivery: FTP, SMTP and Web-Panel.

As seen, the malware uses a number of RATs to control its victims or track their activity. One of the threat actor’s successful implementations contained the well-known DarkComet. This convenient “choose your RAT” functionality plays a very important role in the malware infection, routine and survival on the victim’s machine. The DarkComet samples are more complicated than the traditional HawkEye logger. One instance had a random key generator which sets an initialization vector of the first 4 bytes of the executable file and appends a random 5 byte key that unpacks another PE file, less than 20Kb in size. The PE file then contains another packer with an even more challenging obfuscation technique. The last sample we tested had still more complicated behavior. The code itself had the same obfuscation technique, though traffic was not transferring in clear text. Stolen data was packed and sent encrypted over HTTP random ports. This means that the group is trying to produce other types of malicious samples with different RATs.

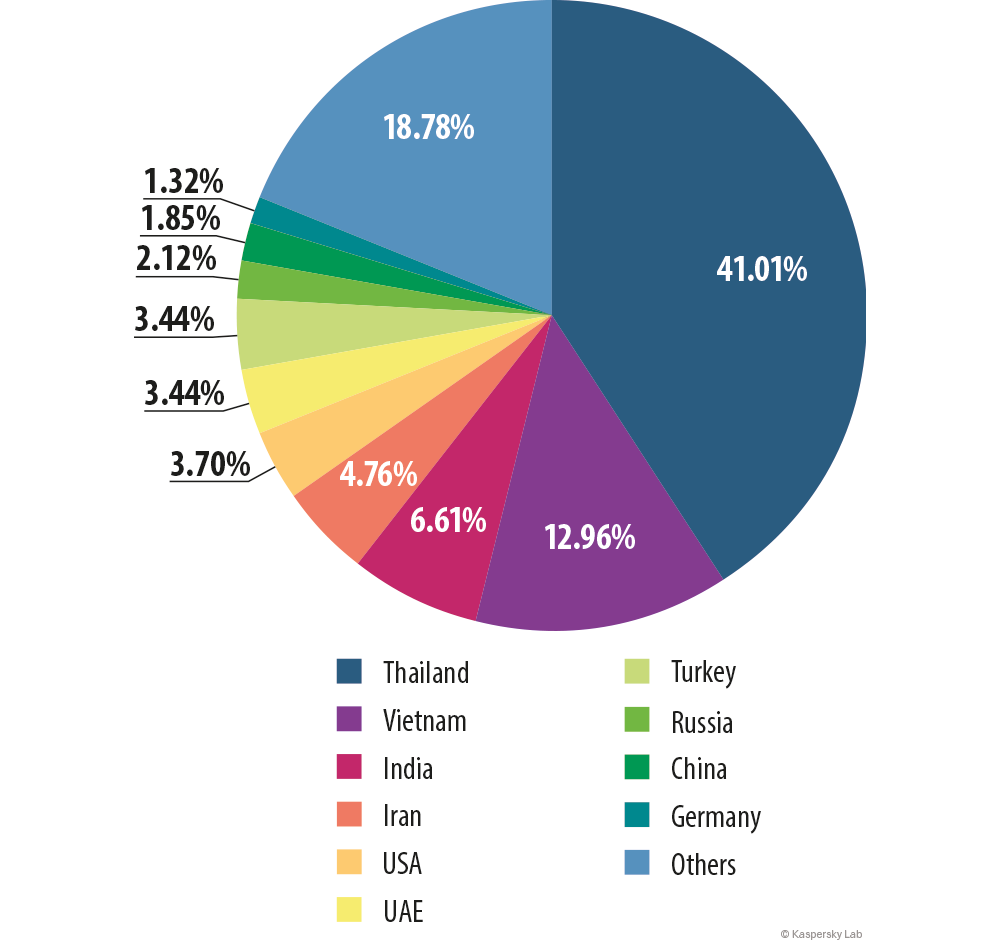

Approximately 10,000 stolen files have been collected. Companies based in Thailand and India had the largest percentage of infected machines. By looking at the stolen credentials, it is very clear that employees sent the malware to one another, as stolen host names and internal applications are the same.

The following is the full chart, updated to May 2015:

Malware distribution by country

Demonstrating the effectiveness of their simple Keyloggers, one C2 (on May 15th) maintained thousands of victim account credentials from hundreds of infected systems.

To sum it up, Grabit threat actors did not use any sophisticated evasions or maneuvers in their dynamic activity. It is interesting to see the major differences between the core development of the malware and the actual functionality it uses.

Some malware samples used the same hosting server, and even the same credentials. Could it be that our threat actor was in a hurry?

Our guess is that we are looking at a group and not an individual. Some members of the group are more technical than the others and some are more security oriented and aware of the risks they might expose themselves to.

Back to square one:

From what we have seen so far, the malware is being delivered as a Microsoft Office Word (.doc) email attachment, containing a malicious macro called AutoOpen. This macro simply opens a socket over TCP and sends an HTTP request to a remote server that was hacked by the group to serve as a malware hub, before downloading the malware. In some cases the malicious macro was password protected, but our threat actor might have forgotten that a .doc file is actually an archive and when that archive is opened in a convenient editor of your choice, the macro strings are shown in clear-text.

The malware is in plain view, modifying commonplace registry entries, such as the startup configurations, and not covering its tracks. Its binaries are not deleted in most cases, and its communication is in clear-text, where the victim can sniff the communication and grab the FTP/SMTP server’s credentials.

Malware derivatives are mainly located in:

C:\Users\ <user> \AppData\Roaming\Microsoft

Phishing extensions: .doc

3f77403a64a2dde60c4962a6752de601d56a621a

4E7765F3BF73AEC6E350F412B623C23D37964DFC

Icons: .pdf, .doc, .ttf, .xls, .ppt, .msg, .exe

Stealer: .txt, .jpeg, .eml

Additional Executable names:

AudioEndpointBuilder.exe

BrokerInfrastructure.exe

WindowsUpdate.exe

Malware extensions: .zip or .exe

9b48a2e82d8a82c1717f135fa750ba774403e972b6edb2a522f9870bed57e72a

ea57da38870f0460f526b8504b5f4f1af3ee490ba8acfde4ad781a4e206a3d27

0b96811e4f4cfaa57fe47ebc369fdac7dfb4a900a2af8a07a7b3f513eb3e0dfa

1948f57cad96d37df95da2ee0057dd91dd4a9a67153efc278aa0736113f969e5

1d15003732430c004997f0df7cac7749ae10f992bea217a8da84e1c957143b1c

2049352f94a75978761a5367b01d486283aab1b7b94df7b08cf856f92352166b

26c6167dfcb7cda40621a952eac03b87a2f0dff1769ab9d09dafd09edc1a4c29

2e4507ff9e490f9137b73229cb0cd7b04b4dd88637890059eb1b90a757e99bcf

3928ea510a114ad0411a3528cd894f6b65f59e3d52532d3e0c35157b1de27651

710960677066beba4db33a62e59d069676ffce4a01e63dc968ad7446158f55d6

7371983a64ef9389bf3bfa8d2abacd3a909d13c3ee8b53cccf437026d5925df5

76ba61e510a340f8751e46449a7d857a2d242bd4724d0d040b060137ab5fb31a

78970883afe52e4ee846f4a7cf75b569f6e5a8e7a830d69358a8b33d186d6fec

7c8c3247ffeb269dbf840c7648e9bfaa8cf3d375a03066b57773c48de2b6d477

7f0c4d3644fdcd8ac5bc2e007bb5c3e9eab56a3d2d470bb796af88125cd74ac9

IP Addresses:

31.220.16.147

204.152.219.78

128.90.15.98

31.170.163.242

185.77.128.65

193.0.200.136

208.91.199.223

31.170.164.81

185.28.21.35

185.28.21.32

112.209.76.184

Grabit and the RATs

Linda Nelson

Ido,

I found a site that has exactly what you described – Hawkeye_Keylogger_Execution Contirmed … but do not want to give you the link because there are MANY passwords that I can see!

Please reply so I can send you the real thing! It is a treasure-trove of personal information.

Linda

Linda Nelson

IDO

I do not want to post the link publicly because I’d be revealing other people’s personal secure data. Please send me your private email. Will not post the info here. Thanks

Ido Naor

You can send me a message via Twitter and we can share details.

Thanks again,

Ido

Ido Naor

Thank you very much Linda, please send me the link

Hector Suarez Planas

Hi, Ido Naor.

Can you tell us what are de TCP/UDP port that Grabit use. It’s posible to have more IP addresses than that.

Ido Naor

Hi Hector,

The ports are not constant. It depends mostly on the RAT implementation the attacker decided to use. The obvious ones were 21, 25, 80, 443, 587 etc, but sometimes 9009, 5001, 5005 and so on.

Each sample has its own characteristics.

Regards,

Ido

Hector Suarez Planas

Greetings, Ido.

Thanks for reply. The deny of the Grabit IP group was added on my routers and services.

🙂