Web injection attacks

There’s an entire class of attacks that targets browsers – so-called Man-in-the-Browser (MITB) attacks. These attacks can be implemented using various means, including malicious DLLs, rogue extensions, or more complicated malicious code injected into pages in the browser by spoofing proxy servers or other ways. The purpose of an MITB attack may vary from relatively innocuous ad spoofing on social networks or popular websites to stealing money from user accounts – the latter is what happened in the Lurk case.

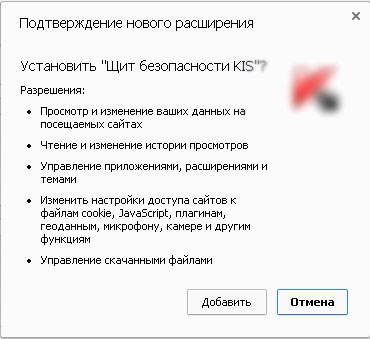

A malicious app masquerades as a Kaspersky Lab product in an MITB attack

Web injection is used in most cases when an MITB-class attack targets online banking. This type of web injection attack involves malicious code being injected into an online banking service webpage to intercept the one-time SMS message, harvest information about the user, spoof banking details, etc. For example, our Brazilian colleagues have long reported about barcode spoofing attacks performed when users print out Boletos – popular banking documents issued by banks and all kind of businesses in Brazil.

Meanwhile, the prevalence of MITB attacks in Russia is decreasing – cybercriminals are opting for other methods and attack vectors to target banking clients. For the average cybercriminal, it is much easier to use readily available tools than develop and implement web injection tools.

Despite this, we’re often asked if there are any web injection attacks for Android devices. This is our attempt to investigate and give as full an answer as possible.

Web injection on Android

Despite the term ‘inject’ being used in connection with mobile banking Trojans (and sometimes used by cybercriminals to refer to their data-stealing technologies), Android malware is a whole different world. In order to achieve the same goals pursued by web injection tools on computers, the creators of mobile Trojans use two completely different technologies: overlaying other apps with a phishing window, and redirecting the user from a banking web page to a specially crafted phishing page.

Overlaying apps with phishing windows

This is the most popular technology with cybercriminals and is used in practically all banking Trojans. 2013 was when we first encountered a piece of malware overlaying other apps with its phishing window – that was Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Svpeng.

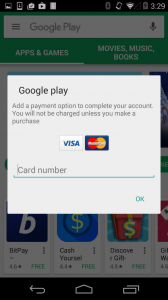

Today’s mobile banking Trojans most often overlay the Google Play Store app with their phishing window – this is done in order to steal the user’s bank card details.

The Marcher malware

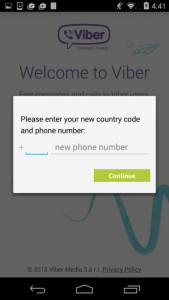

Besides this, Trojans often overlay various social media and instant messaging apps and steal the passwords to them.

The Acecard malware

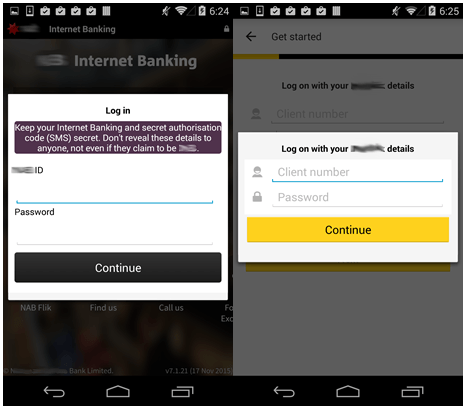

However, mobile banking Trojans typically target financial applications, mostly banking apps.

Three methods of MITB attacks for mobile OS can be singled out:

1. A special Trojan window, crafted beforehand by cybercriminals, is used to overlay another app’s window. This method was used, for example, by the Acecard family of mobile banking Trojans.

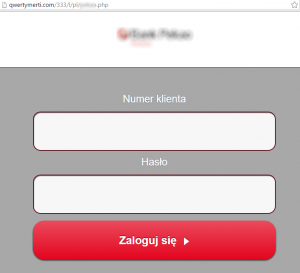

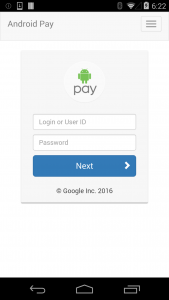

Acecard phishing windows

2. Apps are overlaid with a phishing web page located on a malicious server. This way, the cybercriminals can modify its contents any time they need to. This method is used by the Marcher family of banking Trojans.

Marcher phishing page

3. A template page is downloaded from a malicious server, to which the icon and the name of the attacked application is added. This is how one of the Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Faketoken modifications manages to attack over 2,000 financial apps.

FakeToken phishing page

It should be noted that starting from Android 6, for the above attack method to work, the FakeToken Trojan has to request the privilege of displaying its window on top of other app windows. It’s not alone though: as new versions of Android are gaining popularity, a growing number of mobile banking Trojans are beginning to request such privileges.

Redirecting the user from the bank’s page to a phishing page

We were only able to identify the use of this technology in the Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Marcher family. The earliest versions of the Trojan that redirected the user to a phishing page are dated late April 2016, and the latest are from the first half of November 2016.

Redirecting the user from a bank’s webpage to a phishing page works as follows. The Trojan subscribes to modify browser bookmarks, which includes changes in the current open page. This way the Trojan knows which webpage is currently open, and if it happens to be one of the targeted pages, the Trojan opens the corresponding phishing page in the same browser and redirects the user there. We were able to find over a hundred web pages belonging to financial organizations that were targeted by the Marcher family of Trojans.

However, two points need to be raised:

- All new modifications of the Marcher Trojan that we were able to detect no longer use this technology.

- Those modifications that used this technology also used a method of overlaying other apps with their phishing window.

Why then was the method of redirecting the user to a phishing page used by only one family of mobile banking Trojans, and why is this technology no longer used in newer modifications of the family? There are several reasons:

- In Android 6 and later versions, this technology no longer works, meaning the number of potential victims is decreasing every day. For example, around 30% of those using Kaspersky Lab’s mobile security solutions now use Android 6 or a later version;

- The technology only worked on a limited number of mobile browsers;

- The user can easily spot that they are being redirected to a phishing site and they may also notice that the URL of the webpage has changed.

Attacks launched using root privileges

With superuser privileges, Trojans can perform any attack, including real malicious injections into browsers. Although we were unable to find a single case of this happening, the following should be noted:

- Some modules of Backdoor.AndroidOS.Triada can substitute websites in certain browsers, using superuser privileges. All the attacks we found were launched with the purpose of making some money from advertising only, and did not result in the theft of banking information.

- The banking Trojan Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Tordow, using superuser privileges, can steal passwords saved in browsers, which may include passwords to financial websites.

Conclusions

We can state that, despite all the available technical capabilities, cybercriminals that target banks do not make use of malicious web injections in mobile browsers or injections in mobile apps. Sometimes they use these technologies to spoof adverts, but even then that requires highly sophisticated malicious software.

So why do cybercriminals ignore the available opportunities? Most probably it is because of the diversity of mobile browsers and apps. Malware writers would have to adapt their creations to a long list of programs, which is rather costly, while simpler and more versatile attacks involving phishing windows do not require so much effort to target a larger number of users.

Nonetheless, the Triada and Tordow examples suggest that similar attacks may well take place in the future as malware creators gain more expertise.

Do web injections exist for Android?