The growing popularity of car sharing services has led some experts to predict an end to private car ownership in big cities. The statistics appear to back up this claim: for example, in 2017 Moscow saw the car sharing fleet, the number of active users and the number of trips they made almost double. This is great news, but information security specialists have started raising some pertinent questions: how are the users of these services protected and what potential risks do they face in the event of unauthorized access to their accounts?

Why is car sharing of interest to criminals?

The simple answer would be because they want to drive a nice car at somebody else’s expense. However, doing so more than once is likely to be problematic – once the account’s owner finds out they have been charged for a car they never rented, they’ll most likely contact the service’s support line, the service provider will check the trip details, and may eventually end up reporting the matter to the police. It means anyone trying it a second time will be tracked and caught red-handed. This is obvious and makes this particular scenario the least likely reason for hijacking somebody’s account.

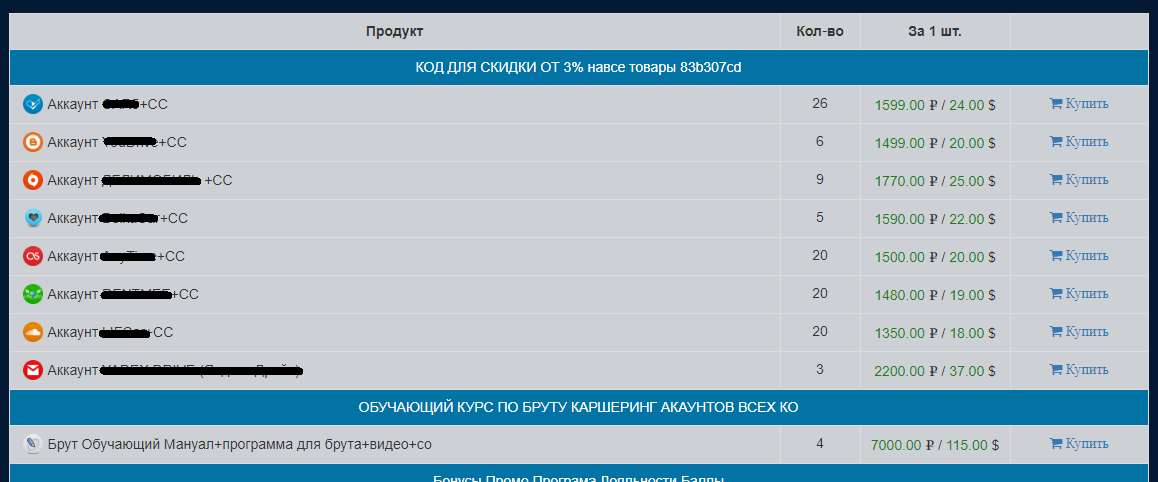

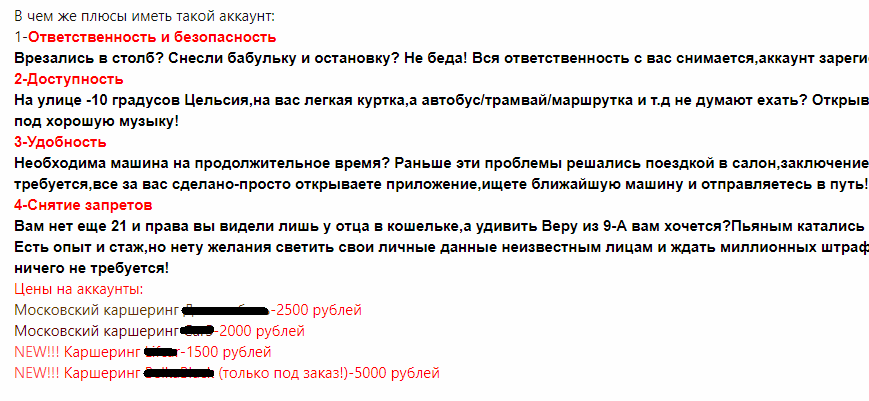

The selling of hijacked accounts appears to be a more viable reason. There is bound to be demand from those who don’t have a driving license or those who were refused registration by the car sharing service’s security team. Indeed, offers of this nature already exist on the market.

In addition, someone who knows the details of a user’s car sharing account can track all their trips and steal things that are left behind in the car. And, of course, a car that is fraudulently rented in somebody else’s name can always be driven to some remote place and cannibalized for spare parts.

Application security

So, we know there is potential interest among criminal elements; now let’s see if the developers of car sharing apps have reacted to it. Have they thought about user security and protected their software from unauthorized access? We tested 13 mobile apps and (spoiler alert!) the results were not very encouraging.

We started by checking the apps’ ability to prevent launches on Android devices with root privileges, and assessed how well the apps’ code is obfuscated. This was done for two reasons:

- the vast majority of Android applications can be decompiled, their code modified (e.g. so that user credentials are sent to a C&C), then re-assembled, signed with a new certificate and uploaded again to an app store;

- an attacker on a rooted device can infiltrate the process of the necessary application and gain access to authentication data.

Another important security element is the ability to choose a username and password when using a service. Many services use a person’s phone number as their username. This is quite easy for cybercriminals to obtain as users often forget to hide it on social media, while car sharing users can be identified on social media by their hashtags and photos.

We then looked at how the apps work with certificates and if cybercriminals have any chance of launching successful MITM attacks. We also checked how easy it is to overlay an application’s interface with a fake authorization window.

Reverse engineering and superuser privileges

Of all the applications we analyzed, only one was capable of countering reverse engineering. It was protected with the help of DexGuard, a solution whose developers also promise that protected software will not launch on a device where the owner has gained root privileges or that has been modified (patched).

However, while that application is well protected against reverse engineering, there’s nothing to stop it from launching on an Android device with superuser privileges. When tested that way, the app launches successfully and goes through the server authorization process. An attacker could obtain the data located in protected storage. However, in this particular app the data was encrypted quite reliably.

Password strength

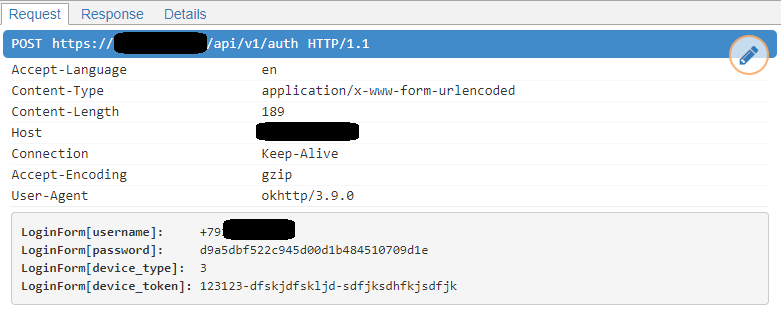

Half the applications we tested do not allow the user to create their own credentials; instead they force the user to use their phone number and a PIN code sent in a text message. On the one hand, this means the user can’t set a weak password like ‘1234’; on the other hand, it presents an opportunity for an attacker to obtain the password (by intercepting it using the SS7 vulnerability, or by getting the phone’s SIM card reissued). We decided to use our own accounts to see how easy it is to find out the ‘password’.

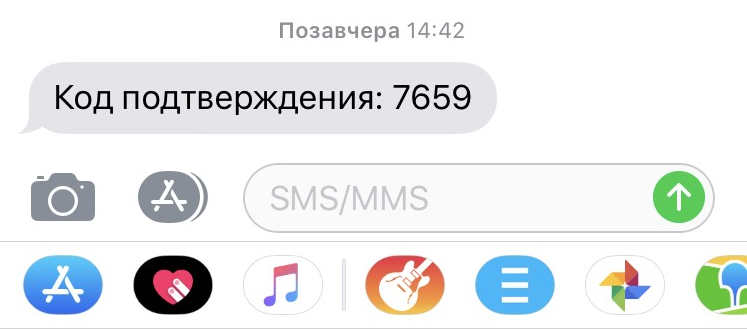

If an attacker finds a person’s phone number on social media and tries to use it to log in to the app, the owner will receive an SMS with a validation code:

As we can see, the validation code is just four digits long, which means it only takes 10,000 attempts to guess it – not such a large number. Ideally, such codes should be at least six digits long and contain upper and lower case characters as well as numbers.

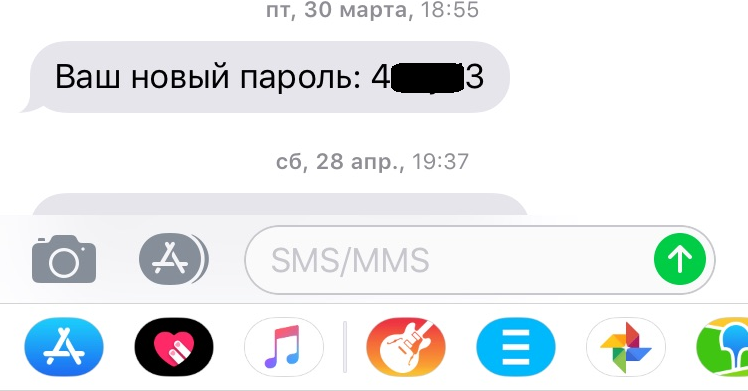

Another car sharing service sends stronger passwords to users; however, there is a drawback to that as well. Its codes are created following a single template: they always have numbers in first and last place and four lower-case Latin characters in the middle:

That means there are 45 million possible combinations to search through; if the positioning of the numbers were not restricted, the number of combinations would rise to two billion. Of course, 45,000,000 is also large amount, but the app doesn’t have a timeout for entering the next combination, so there are no obstacles to prevent brute forcing.

Now, let’s return to the PIN codes of the first application. The app gives users a minute to enter the PIN; if that isn’t enough time, users have to request a new code. It turned out that the combination lifetime is a little over two minutes. We wrote a small brute force utility, reproduced part of the app/server communication protocol and started the brute force. We have to admit that we were unable to brute force the code, and there are two possible reasons for that. Firstly, our internet line may have been inadequate, or secondly, the car sharing operator set an appropriate two-minute timeout for the PIN code, so it couldn’t be brute forced within two minutes even with an excellent internet connection. We decided not to continue, confirming only that the service remained responsive and an attack could be continued after several attempts at sending 10,000 requests at a time.

While doing so, we deliberately started the brute force in a single thread from a single IP address, thereby giving the service a chance to detect and block the attack, contact the potential victim and, as a last resort, deactivate the account. But none of these things happened. We decided to leave it at that and moved on to testing the next application.

We tried all the above procedures on the second app, with the sole exception that we didn’t register a successful brute force of the password. We decided that if the server allows 1,000 combinations to be checked, it would probably also allow 45 million combinations to be checked, so it is just a matter of time.

This is a long process with a predictable result. This application also stores the username and password locally in an encrypted format, but if the attacker knows their format, brute forcing will only take a couple of minutes – most of this time will be spent on generating the password/MD5 hash pair (the password is hashed with MD5 and written in a file on the device).

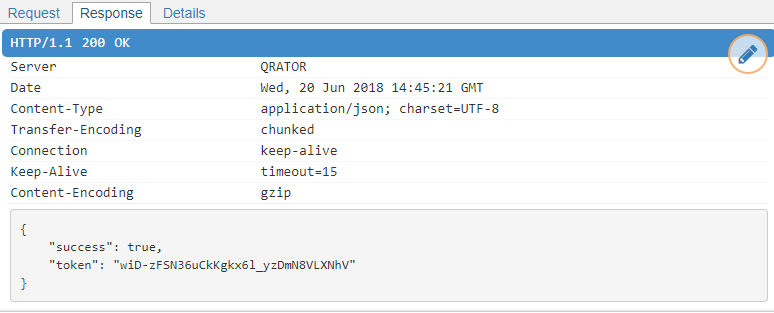

MITM attack

It’s worth noting that the applications use HTTPS to communicate data to and from their control centers, so it may take quite a while to figure out the communication protocol. To make our ‘attack’ faster, we resorted to an MITM attack, aided by another global security flaw: none of the tested applications checks the server’s certificate. We were able to obtain the dump of the entire session.

Protection from overlaying

Of course, it’s much faster and more effective (from the attacker’s point of view) if an Android device can be infected, i.e., the authorization SMS can be intercepted, so the attacker can instantly log in on another device. If there’s a complex password, then the attacker can hijack the app’s launch by showing a fake window with entry fields for login details that covers the genuine app’s interface. None of the applications we analyzed could counter this sort of activity. If the operating system version is old enough, privileges can be escalated and, in some cases, the required data can be extracted.

Outcome

The situation is very similar to what we found surrounding Connected Car applications. It appears that app developers don’t fully understand the current threats to mobile platforms – that goes for both the design stage and when creating the infrastructure. A good first step would be to expand the functionality for notifying users of suspicious activities – only one service currently sends notifications to users about attempts to log in to their account from a different device. The majority of the applications we analyzed are poorly designed from a security standpoint and need to be improved. Moreover, many of the programs are not just very similar to each other but are actually based on the same code.

Russian car sharing operators could learn a thing or two from their colleagues in other countries. For example, a major player in the market of short-term car rental only allows clients to access a car with a special card – this may make the service less convenient, but dramatically improves security.

Advice for users

- Don’t make your phone number publicly available (the same goes for your email address)

- Use a separate bank card for online payments, including car sharing (a virtual card also works) and don’t put more money on it than you need.

- If your car sharing service sends you an SMS with a PIN code for your account, contact the security service and disconnect your bank card from that account.

- Do not use rooted devices.

- Use a security solution that will protect you from cybercriminals who steal SMSs. This will make life harder not only for free riders but also for those interested in intercepting SMSs from your bank.

Recommendations to car sharing services

- Use commercially available packers and obfuscators to complicate reverse engineering. Pay special attention to integrity control, so the app can’t be modified.

- Use mechanisms to detect operations on rooted devices.

- Allow the user to create their own credentials; ensure all passwords are strong.

- Notify users about successful logons from other devices.

- Switch to PUSH notifications: it’s still rare for malware to monitor the Notification bar in Android.

- Protect your application interface from being overlaid by another app.

- Add a server certificate check.

A study of car sharing apps