Background

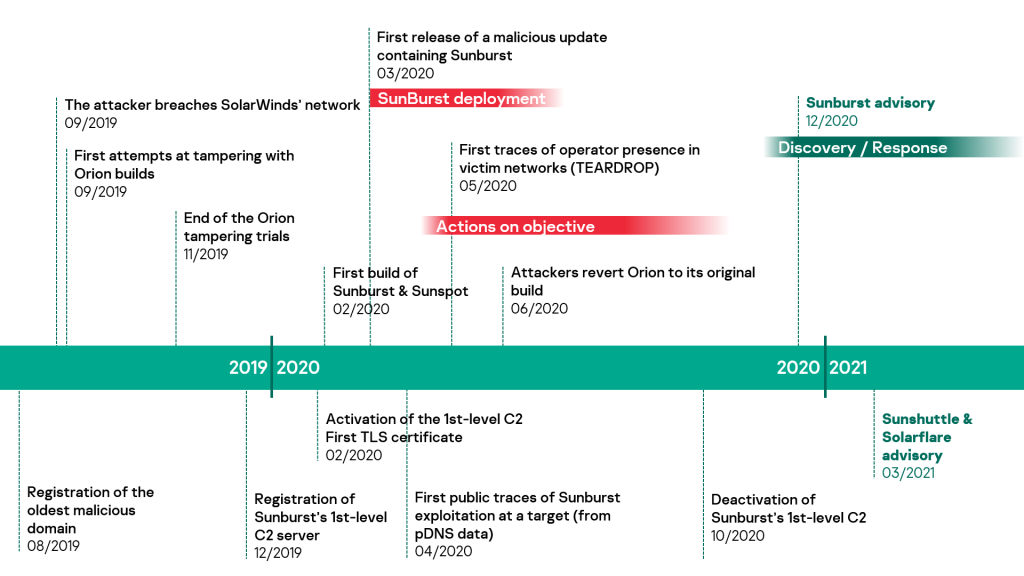

In December 2020, news of the SolarWinds incident took the world by storm. While supply-chain attacks were already a documented attack vector leveraged by a number of APT actors, this specific campaign stood out due to the extreme carefulness of the attackers and the high-profile nature of their victims. It is believed that when FireEye discovered the first traces of the campaign, the threat actor (DarkHalo aka Nobelium) had already been working on it for over a year. Evidence gathered so far indicates that DarkHalo spent six months inside OrionIT’s networks to perfect their attack and make sure that their tampering of the build chain wouldn’t cause any adverse effects.

The first malicious update was pushed to SolarWinds users in March 2020, and it contained a malware named Sunburst. We can only assume that DarkHalo leveraged this access to collect intelligence until the day they were discovered. The following timeline sums up the different steps of the campaign:

Kaspersky’s GReAT team also investigated this supply-chain attack, and released two blog posts about it:

- In December 2020, we analyzed the DNS-based protocol of the malicious implant and determined it leaked the identity of the victims selected for further exploitation by DarkHalo.

- One month later, we discovered interesting similarities between Sunburst and Kazuar, another malware family linked to Turla by Palo Alto.

In March 2021, FireEye and Microsoft released additional information about the second-stage malware used during the campaign, Sunshuttle (aka GoldMax). Later in May 2021, Microsoft also attributed spear-phishing campaign impersonating a US-based organization to Nobelium. But by then the trail had already gone cold: DarkHalo had long since ceased operations, and no subsequent attacks were ever linked to them.

DNS hijacking

Later this year, in June, our internal systems found traces of a successful DNS hijacking affecting several government zones of a CIS member state. These incidents occurred during short periods in December 2020 and January 2021 and allowed the malicious threat actor to redirect traffic from government mail servers to machines they controlled.

| Zone | Period during which the authoritative servers were malicious | Hijacked domains |

| mfa.*** | December 22-23, 2020 and January 13-14, 2021 |

mail.mfa.*** kk.mfa.*** |

| invest.*** | December 28, 2020 to January 13, 2021 | mail.invest.*** |

| fiu.*** | December 29, 2020 to January 14, 2021 | mx1.fiu.*** mail.fiu.*** |

| infocom.*** | January 13-14, 2021 | mail.infocom.*** |

During these time frames, the authoritative DNS servers for the zones above were switched to attacker-controlled resolvers. These hijacks were for the most part relatively brief and appear to have primarily targeted the mail servers of the affected organizations. We do not know how the threat actor was able to achieve this, but we assume they somehow obtained credentials to the control panel of the registrar used by the victims.

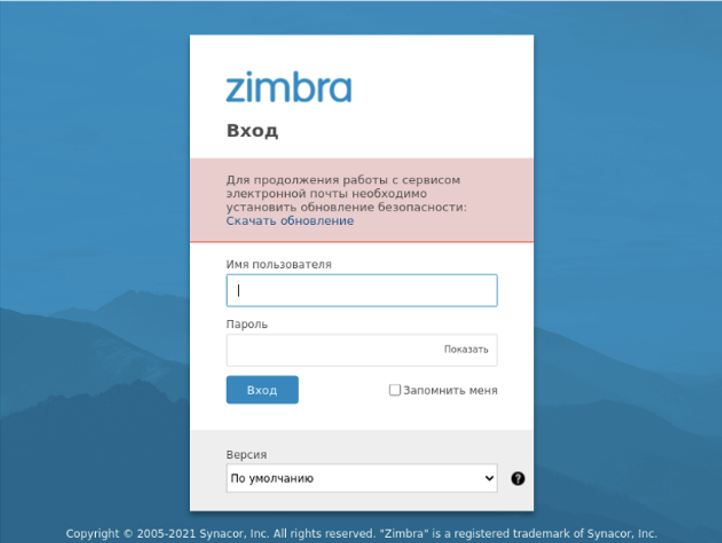

While the malicious redirections were active, visitors were directed to webmail login pages that mimicked the original ones. Due to the fact that the attackers controlled the various domain names they were hijacking, they were able to obtain legitimate SSL certificates from Let’s Encrypt for all these fake pages, making it very difficult for non-educated visitors to notice the attack – after all, they were connecting to the usual URL and landed on a secure page.

Malicious webmail login page set up by the attackers

In all likelihood, any credentials typed in such webpages were harvested by the attackers and reused in subsequent stages of the attack. In some cases, they also added a message on the page to trick the user into installing a malicious “security update”. In the screenshot above, the text reads: “to continue working with the email service, you need to install a security update: download the update”.

The link leads to an executable file which is a downloader for a previously unknown malware family that we now know as Tomiris.

Tomiris

Tomiris is a backdoor written in Go whose role is to continuously query its C2 server for executables to download and execute on the victim system. Before performing any operations, it sleeps for at least nine minutes in a possible attempt to defeat sandbox-based analysis systems. It establishes persistence with scheduled tasks by creating and running a batch file containing the following command:

|

1 |

SCHTASKS /CREATE /SC DAILY /TN StartDVL /TR "[path to self]" /ST 10:00 |

The C2 server address is not embedded directly inside Tomiris: instead, it connects to a signalization server that provides the URL and port to which the backdoor should connect. Then Tomiris sends GET requests to that URL until the C2 server responds with a JSON object of the following structure:

|

1 |

{"filename": "[filename]", "args": "[arguments]", "file": "[base64-encoded executable]"} |

This object describes an executable that is dropped on the victim machine and run with the provided arguments. This feature and the fact that Tomiris has no capability beyond downloading more tools indicates there are additional pieces to this toolset, but unfortunately we have so far been unable to recover them.

We also identified a Tomiris variant (internally named “SBZ”, MD5 51AA89452A9E57F646AB64BE6217788E) which acts as a filestealer, and uploads any recent file matching a hardcoded set of extensions (.doc, .docx, .pdf, .rar, etc.) to the C2.

Finally, some small clues found during this investigation indicate with low confidence that the authors of Tomiris could be Russian-speaking.

The Tomiris connection

While analyzing Tomiris, we noticed a number of similarities with the Sunshuttle malware discussed above:

- Both malware families were developed in Go, with optional UPX packing.

- The same separator (“|”) is used in the configuration file to separate elements.

- In the two families, the same encryption/obfuscation scheme is used to encode configuration files and communicate with the C2 server.

- According to Microsoft’s report, Sunshuttle relied on scheduled tasks for persistence as well.

- Both families comparably rely on randomness:

- Sunshuttle randomizes its referrer and decoy URLs used to generate benign traffic. It also sleeps 5-10 seconds (by default) between each request.

- Tomiris adds a random delay (0-2 seconds or 0-30 seconds depending on the context) to the base time it sleeps at various times during the execution. It also contains a list of target folders to drop downloaded executables, from which the program chooses at random.

- Tomiris and Sunshuttle both gratuitously reseed the RNG with the output of Now() before each call.

- Both malware families regularly sleep during their execution to avoid generating too much network activity.

- The general workflow of the two programs, in particular the way features are distributed into functions, feel similar enough that this analyst feels they could be indicative of shared development practices. An example of this is how the main loop of the program is transferred to a new goroutine when the preparation steps are complete, while the main thread remains mostly inactive forever.

- English mistakes were found in both the Tomiris (“isRunned”) and Sunshuttle (“EXECED” instead of “executed”) strings.

None of these items, taken individually, is enough to link Tomiris and Sunshuttle with sufficient confidence. We freely admit that a number of these data points could be accidental, but still feel that taken together they at least suggest the possibility of common authorship or shared development practices.

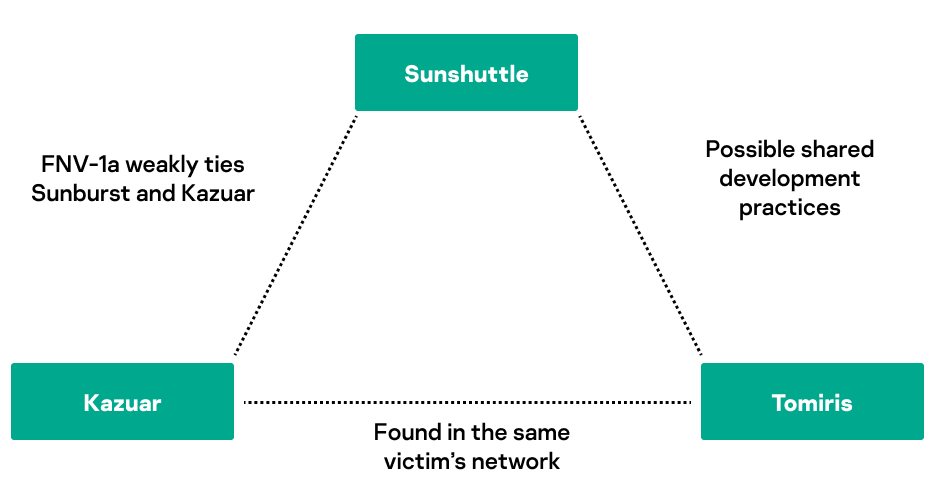

A final piece of circumstantial evidence we would like to present is the discovery that other machines in a network infected with Tomiris were infected with the Kazuar backdoor. Unfortunately, the available data doesn’t allow us to determine whether one of the malicious programs leads to the deployment of the other, or if they originate from two independent incidents.

The next diagram sums up the weak links we were able to uncover between the three malware families mentioned in this article:

In the end, a number of clues hint at links between Sunburst, Kazuar and Tomiris, but it feel like we’re still missing one piece of evidence that would allow us to attribute them all to a single threat actor. We would like to conclude this segment by addressing the possibility of a false flag attack: it could be argued that due to the high-profile nature of Sunshuttle, other threat actors could have purposefully tried to reproduce its design in order to mislead analysts. The earliest Tomiris sample we are aware of appeared in February 2021, one month before Sunshuttle was revealed to the world. While it is possible that other APTs were aware of the existence of this tool at this time, we feel it is unlikely they would try to imitate it before it was even disclosed. A much likelier (but yet unconfirmed) hypothesis is that Sunshuttle’s authors started developing Tomiris around December 2020 when the SolarWinds operation was discovered, as a replacement for their burned toolset.

Conclusions

If our guess that Tomiris and Sunshuttle are connected is correct, it would shed new light on the way threat actors rebuild capacities after being caught. We would like to encourage the threat intelligence community to reproduce this research, and provide second opinions about the similarities we discovered between Sunshuttle and Tomiris. In order to bootstrap efforts, Kaspersky is pleased to announce a free update to our Targeted Malware Reverse Engineering class, featuring a whole new track dedicated to reverse engineering Go malware and using Sunshuttle as an example. The first two parts are also available on YouTube:

For more information about Tomiris, subscribe to our private reporting services: intelreports@kaspersky.com

Indicators of compromise

Tomiris Downloader

109106feea31a3a6f534c7d923f2d9f7

7f8593f741e29a2a2a61e947694445f438b33380

8900cf88a91fa4fbe871385c8747c7097537f1b5f4a003418d84c01dc383dd75

fd59dd7bb54210a99c1ed677bbfc03a8

292c3602eb0213c9a0123fdaae522830de3fad95

c9db4f661a86286ad47ad92dfb544b702dca8ffe1641e276b42bec4cde7ba9b4

Tomiris

6b567779bbc95b9e151c6a6132606dfe

a0de69ab52dc997ff19a18b7a6827e2beeac63bc

80721e6b2d6168cf17b41d2f1ab0f1e6e3bf4db585754109f3b7ff9931ae9e5b

Tomiris staging server

51.195.68[.]217

Tomiris signalization server

update.softhouse[.]store

Tomiris C2

185.193.127[.]92

185.193.126[.]172

Tomiris build path

C:/Projects/go/src/Tomiris/main.go

DarkHalo after SolarWinds: the Tomiris connection

virendra

amazing article , appreciate the endeavors looking forward to the response from the experts now

moustaffa

i wantu servez my kasperty my computer