Early reporting blind to likely external KCNA attacker

Security researchers recently announced that that the official website for the Korean Central News Agency of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea has been serving malware disguised as a Flash Player update. The immediately conspicuous code is still active on the KCNA front page. The javascript variables at the top of the front page source code are part of an interwoven js mechanism meant to check for specific requirements before redirecting the visitor to a relative location, /download/FlashPlayer10.zip.

The malware delivery site has been live, although response to connection attempts is intermittent at best. The zip file contains two executables with the common Flash installer names.This malware has been around since the end of 2012.

What appears to be rushed attribution and pretty faux-intelligence diagrams proposes the standard hypothesis that the malware was placed there by the site’s developers in an attempt to infect the endpoints of those outsiders interested in the goings-on of the DPRK. This may not be the case, because incidents are usually more complex than they seem. And clearly, this is a significant piece of the puzzle – there was human involvement in adding this web page filtering. It is not a part of the viral routines in its handful of components. Instead, the malware’s trigger, system requirements, and technical and operational similarities with the more recent DarkHotel campaigns point in the direction of an external actor, possibly looking to keep tabs on the geographically dispersed DPRK internet-enabled elite.

The larger spread of victims include telecommunications network engineering staff, wealth management and trading staff, a pharmaceutical’s electrical engineering staff, distributed software development teams, business management and related school faculty and IT, and many, many more.

Website Attack and Geographic Spread

One of the most notable characteristics is that the malware isn’t being delivered to every site visitor. The delivery trigger is contingent on the absence of the legitimate Flash Player 10 or newer being present on the target’s Windows system. If a user attempts to view the videos or picture slideshows linked on the bottom right pane of the front page, the user is presented with a gif in place of the desired content indicating that flash player is required. Naturally, clicking on the gif will redirect to the malicious zip file. It’s also interesting that this malware has no Linux or OS X variant, deliverables are exclusively Windows executables. It’s also interesting that the malware components were first detected in Nov of 2012, two months prior to the first known appearance of the Flashplayer bundle on the kcna.kp website. While we don’t know definitively the exact origin of these infections, at this point, we suspect it was in fact the kcna website. There are no other known sources.

KSN data also includes few select cases where Firefox users were served up the malware while visiting a page known for cross-site scripting, described in the following section “Potential XSS-Enabled Watering Hole”. Basically, the timing and resource location of this vulnerability presents the definite possibility of an external actor’s intrusion.

The delivery of a zip file dependent on user interaction and self-infection initially implies a fairly low level of attack sophistication, but let’s go farther than the social engineering elements of the attack and consider the victim profiling too. From this web site in particular, the attackers are initially targeting users with not only a low-level of technical expertise and general knowledge, but also tragically outdated Windows systems. Flash Player version 10 was released on October 2008, and newer browsers like Google Chrome include a more recent flash plug-in out of the box. These attacks took place in the third quarter of 2012 at the earliest.

Most likely, the intended victims are known to use outdated systems that fit these specifications. This is the case in North Korea, where Global Stats places nearly half of desktop computers systems still running Windows XP. In comparison, South Korea has a steady Windows 7 adoption rate of nearly 80% over the past year.

So what is the actual geographic spread of the malware? Well, the two main associated components mscaps.exe and wtime32.dll were detected on systems mostly in China, followed by South Korea, and Russia. We can infer that these systems were infected at some point and were victim systems of the kcna.kp spread malware:

| China | 450 |

| Korea, Republic of | 43 |

| Russian Federation | 25 |

| Malaysia | 20 |

| Italy | 11 |

| India | 10 |

| Korea, Democratic People’s Republic of | 7 |

| Germany | 7 |

| Hong Kong | 6 |

| Iran, Islamic Republic of | 4 |

However, reading into the geolocation of the top hits is not as straightforward as it may seem. Reports suggest that NK elites have access to various internet providers that may geolocate their ip in Chinese, Russian, and Hong Kong IP ranges.

Potential XSS-Enabled Watering Hole

Given the recent branding of NK threat actor as the culprit of the Sony hack, original reporting has had no difficulty accepting the idea that this is an attack perpetrated from within the DPRK in order to keep track of those people interested in the official state media. Let’s examine the difficulties in arriving at that conclusion.

First, the site itself was vulnerable to XSS in the early 2013 time frame, when the Flashplayer installer bundle first appeared on the site. The site’s vulnerability is recorded here by “Hexspirit” on XSSed in April 2013. As a matter of fact, the first pages we are aware of that referred to the flashplayer bundle on kcna.kp by the exact same XSS-vulnerable page were seen in Jan 2013:

hxxp://www.kcna.kp/kcna.user.home.photo.retrievePhotoList.kcmsf;jsessionid=xxx

So, the flashplayer bundle may have been delivered by any APT actor and not simply the site’s governmental sponsor. Coupling that possibility with the Darkhotel APT’s penchant for delivering Flashplayer installers from compromised resources, this scenario holds weight. Also, the strong possibility that the site’s developers unknowingly maintained infected machines is present.

The operational angle of placing malware on the state’s official news site is dependent on who is most likely to view this site or directed to it and be interested in its content – to the point of arriving at the download trigger deep in the media section. Sure, we can consider that key elements in the international community, like dissidents, think tanks, and foreign institutions are likely to keep an eye on NK state news but their systems are unlikely to fit the Flash player requirements for the infection. We also have seen forums maintaining emotionally charged discussions containing links to photo images redirecting to the Flash installer malware. Perhaps forum participants were targeted actively in this way as well. So this watering hole attack may be focused inward, intentionally targeting the geographically-spread North Korean internet-enabled elite and other interested readers by an external threat actor.

Malware Similarities to Darkhotel APT Toolset

The original finding includes a preliminary analysis of the quirky inner workings of the malware dropper, delving into the two executables masquerading as Flash Player 10 updates. Let’s go a step further and discuss the following similarities between the viral code hosted on kcna.kp and the previously documented Darkhotel malware in the following categories:

- Social engineering

- Distribution

- Data collection

- Network configuration and simple obfuscation

- Infection and injection behavior

- Timestamps and timelines

A referent for these malware similarities can be found in descriptions of the malware distributed during the DarkHotel campaigns. Comparisons follow.

Social engineering

The most blatant and obvious similarity between these campaigns is the approach of delivering spoofed FlashPlayer installers bound with backdoors from compromised server resources. This is the first page out of the Darkhotel playbook and one of its most distinct qualities now replicated in the KCNA attack. The benefits of this approach are significant, especially when considering that the malware in the case of KCNA is not digitally signed and requires express user interaction for execution.

Data Collection

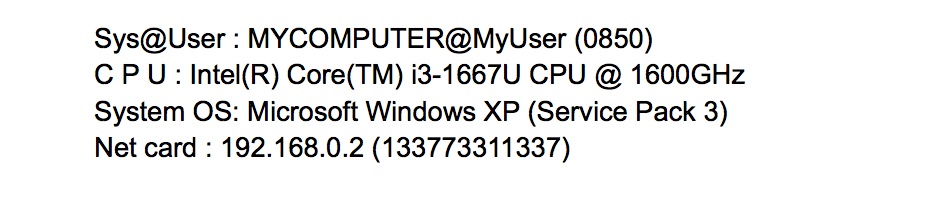

On a technical level, it’s interesting to recall the Darkhotel information stealer from 2012. Its purpose is to collect identifying data points from victim systems. The data points of interest to the DH information stealer are very similar to that of its KCNA equivalent (shown below):

Coincidentally, the KCNA dropper collects much the same identifying data points from victim systems. The Darkhotel item missing from this list is the ‘CPU Name and Identifier’, supplanted by ‘time of infection’.

The Darkhotel stealer maintained the stolen data in a specific internal format of label-colon-value as follows:

The KCNA stealer maintained the stolen data in the following internal format, very similar to the Darkhotel format (label-colon-value):

The KCNA stealer maintained the stolen data in the following internal format, very similar to the Darkhotel format (label-colon-value):

Network configuration and simple obfuscation

This package’s network callback includes several unusual Fully Qualified Domain Names (FQDNs). This network configuration is specifically hardcoded within wtime32.dll:

a.gwas.perl.sh

a-gwas-01.dyndns.org

a-gwas-01.slyip.net

It’s interesting that the malware is configured with three connectback command & control servers, just like the network configuration of tens of the Darkhotel backdoors. Also, a very simple routine locates these strings within the wtime32.dll component’s .data section and decodes them as global variables. Those strings are obfuscated within the binary with a simple XOR 0x12 loop. The later Darkhotel samples maintain a somewhat more complicated approach, but not by much. Here are strangely obfuscated strings:

Software\Microsoft\Active Setup\Installed Components

{ef2b00e3-19da-4e78-b118-6b6451b719f2}

{a96adc11-e20e-4e21-bfac-3e483c40906e}

Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

JREUpdate

mscaps.exe

a.gwas.perl.sh

a-gwas-01.slyip.net

a-gwas-01.dyndns.org

update.microsoft.com

20

%SystemRoot%\system32

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\Protect\SETUP

%SystemRoot%\system32\gdi32.dll

Targeting Specificity

The Darkhotel actor is unusual in the varying degrees of specificity it uses to spread its malware: “This APT precisely drives its campaigns by spear-phishing targets with highly advanced Flash zero-day exploits that effectively evade the latest Windows and Adobe defenses, and yet they also imprecisely spread among large numbers of vague targets with peer-to-peer spreading tactics.”

In other words, the group is surprisingly open to their worms spreading indiscriminately across entire countries, hitting tens of thousands of systems. This is also the case in the KCNA campaign wherein malware is positioned in a way meant to attract a specific target audience with uncommon system requirements and yet the malware itself is designed to spread indiscriminately (via a mechanism described below).

Infection and Injection Behaviors

Much like the Darkhotel toolset, the KCNA malware includes viral code. The routine is maintained in the fil.dll code. After sleeping for a couple of minute intervals, the code repeatedly looks through attached network drives for executables to infect. It infects these files with its explorer shellcode and the @AE1.tmp dropper itself. It’s a strange infection strategy – notably, the shellcode blob does not transfer control back into the original file.

The injection behavior is both intricate and indiscriminate as the malware not only infects executables on network shares but also locally. As an example, the size of an infected Skype installer on a network drive increased in size from its original 1,513 kb to 3,221 kb.

Great strides, however inelegant, were taken in adding to the malware’s injection capabilities beyond simple executables. For this purpose, the malware drops a copy of command-line WinRar version 4.1.0 (released January 2012) in %USERS%\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Identities\\Rar.exe. This Winrar software is used in order to access ZIP, RAR, ISO, and 7Z files in search of any executable contents to infect. Archives in the aforementioned formats containing executables are infected and then repackaged under their original filenames but with their new executable contents under the Daws.awfy scheme.

All resultant infected files are detected by our products as Trojan-Dropper.Win32.Daws.awfy. Several networks were affected by this viral code, and almost one thousand unique md5s representing related infected files across various systems were recorded as “Trojan-Dropper.Win32.Daws.awfy”.

Viral Victimology

Given the malware’s viral propagation capabilities, we can distinguish the infection spread data above, which relates directly to the Flashplayer hosted on KCNA, from the malware’s viral spread through network shares and removable drives. While each count in this list represents a unique organization or system that detected a set of KCNA-viral infected files on their drives, the total infected file detection count is almost 20,000 files. Focusing on the Daws.awfy spread, we get a different picture of the malware’s reach:

| Country | Systems and organzations encountering infected files |

| China | 481 |

| Malaysia | 51 |

| Russia | 47 |

| Korea, Republic of | 34 |

| Taiwan | 14 |

| Senegal | 14 |

| Korea, Democratic People’s Republic of | 11* |

| India | 9 |

| Mexico | 9 |

| Qatar | 9 |

It’s important to note the different conditions that apply to North Korea. First of all, the limited IP space means that multiple unique systems share IP addresses –in the case of DPRK victims above, the number is based on unique systems instead of unique IP addresses. Next, we attribute the relatively low number of network-based infections to the restrictive policies that keep many users from connecting to the larger Internet from KP ip ranges in the first place. A network- and usb-based viral infector is a great tool for a malicious actor to use the few front-facing systems in order to infect computers on an isolated intranet, like the one connecting most machines inside NK. However, that very isolation makes it impossible to precisely quantify the malware’s success inside that intranet at this time.

Timestamps and timelines

KCNA malware dropper compilation timestamp: Tue, 13 Mar 2012 02:24:49 GMT.

Darkhotel information stealer compilation timestamp: Mon, 30 Apr 2012 00:25:59 GMT.

Also interesting is that mostly all of the additional KCNA malware related components were compiled in mid-March 2012.

The first Darkhotel APT spoofed flashplayer installer incidents recorded in our KSN data began in 2012 and peaked in 2013. This KCNA incident would fall in the peak timeframe for this type of offensive activity for Darkhotel.

Noteworthy Components

In addition to the legitimate flash player upgrade that this archive maintains, the backdoor components that it drops to disk and executes seem to be clustered as Windows Live components (i.e.: Defender, IM Messenger). The two most interesting dropped files are the following:

78d3c8705f8baf7d34e6a6737d1cfa18,c:\windows\system32\mscaps.exe

978888892a1ed13e94d2fcb832a2a6b5,c:\windows\system32\wtime32.dll

The mscaps.exe component’s reboot persistence setting is added to the registry here: HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Active Setup\Installed Components\{a96adc11-e20e-4e21-bfac-3e483c40906e}, where its stubpath is set to ‘”C:\WINDOWS\system32\mscaps.exe” /s /n /i:U shell32.dll’. This setting ensures that every time the explorer.exe shell is started or restarted on the system, this executable injects its code.

Other analyses of this malware failed to mention the presence of Madshi’s madCodeHook. It is a legitimate commercial DLL injection and api hooking framework, in this case used to inject the att.dll spyware component specifically into the following communications applications:

- Internet Explorer – iexplore.exe, ieuser.exe

- Mozilla Firefox, firefox.exe

- Google Chrome, chrome.exe

- Microsoft Outlook Express, msimn.exe

- Microsoft Outlook, outlook.exe

- Windows Mail, winmail.exe

- Windows Live Mail, wlmail.exe

- MSN Messenger, msnmsgr.exe

- Yahoo! Messenger, yahoomessenger.exe

- Windows FTP Client, ftp.exe

The LoadLibraryExW hook is placed here:

The hook jmp listed here:

Related string parsing loop here:

Other analysis notes that ws2_32.dll, or the winsock2 library, is dropped to disk and copied to mydll.dll. The reason for this is most likely to maintain stable Winsock2 hooks across Windows OS. In the past, some madCodeHooks set on Winsock2 api proved to be unstable, so these guys just include one that they know works.

This implementation throws a wrench in the works, it is certainly a dissimilarity. The madCodeHook library was not observed in Darkhotel malware.

The wtime32.dll component is dropped to disk and loaded at startup into explorer.exe. It is then injected into each of the listed “interesting” processes. It is a very interesting bot component, communicating with its three c2 domains and listening for further commands. It maintains 13 primitive interactive bot commands:

| Command | Command Description |

| cmd | run provided cmd and output to file as a part of newly created and killed process, i.e. “cmd /c tree > file 2>&1” |

| inf | collect system information – operating system version, username, computername, system drive, local time, all connected drives and properties, network adapter properties, disk free space, enumerate all installed programs as per-user or per-machine |

| cap | capture screenshot and send to c2 |

| dlu | ncomplete function |

| dll | open a process with all access, write a dll to memory and remotely create thread (load a dll into a remote process) |

| put | receive, decrypt, and write specified file to disk |

| got | report status on retrieved file |

| get | collect, encrypt, and retrieve specified file |

| exe | run provided executable name with WinExec |

| del | record file attributes to specified c2 and delete specified file |

| dir | record and report to c2 all files in current directory tree and their attributes: filename, file size, last write time, archive or directory, hidden, system |

| quit | exit thread |

| prc | process request |

Its functionality includes older technologies used here that we just don’t see anymore. Not only does it provide for NTFS, FAT32, FAT16, and FAT filesystem I/O routines, but it implements the older FAT12 I/O routines as well. Low level Windows95 raw disk access is enabled with CreateFileA on \\.\vwin32 through the vwin32 virtual driver.

Finally, the KCNA malware does have a unique trick up its sleeve. Its dropped components’ ability to scan connected drives and network shares to copy their contents and deliver a special something to further its spread. So in its own crude way, this malware could hop across usb-enabled air-gapped networks by infecting both executables and archives on usb sticks.

Conclusions

The KCNA incident and the related viral bot’s spread leaves more questions than solid answers. Chalking this campaign up to DPRK operations is certainly a simplistic thing to do and unsupported here. The possibility for the spread of an internal network virus or the possibility of an XSS-enabled website compromise are both high. Some similarities with the Darkhotel toolset are present, including the network configuration, spoofing technique, as well as the format and selection of stolen data. Were these to be related campaigns, particularities of the KCNA malware show that the Darkhotel actor may still have some tricks up its sleeve.

Appendix

Components Dropped by the KCNA Malware

78d3c8705f8baf7d34e6a6737d1cfa18, mscaps.exe, Tue, 12 Apr 2011 09:15:59 GMT

978888892a1ed13e94d2fcb832a2a6b5, wtime32.dll, 213kb, Trojan.Win32.Agent.hwgw, CompiledOn:Wed, 29 Feb 2012 00:50:36 GMT

2d9df706d1857434fcaa014df70d1c66, arc.dll, 1029kb, Trojan.Win32.Agent.hwgw, CompiledOn:Tue, 13 Mar 2012 02:34:00 GMT

fffa05401511ad2a89283c52d0c86472, att.dll, 229KB, Trojan.Win32.Agent.hwgw, CompiledOn:Tue, 13 Mar 2012 02:24:32 GMT

1fcc5b3ed6bc76d70cfa49d051e0dff6, dis.dll, 120.kb, Trojan.Win32.Agent.hwgw, CompiledOn:Tue, 13 Mar 2012 02:24:36 GMT

d0c9ada173da923efabb53d5a9b28d54, fil.dll, 126kb, UDS:DangerousObject.Multi.Generic, CompiledOn:Tue, 13 Mar 2012 02:24:41 GMT

daac1781c9d22f5743ade0cb41feaebf, launch.exe, 172KB, HEUR:Trojan.Win32.Generic, CompiledOn:Tue, 13 Mar 2012 02:24:52 GMT

6a9461f260ebb2556b8ae1d0ba93858a, sha.dll, 89KB, Trojan.Win32.Agent.hwgw, CompiledOn:Tue, 13 Mar 2012 02:24:43 GMT

f1c9f4a1f92588aeb82be5d2d4c2c730, usd.dll, 99KB, Trojan.Win32.Agent.hwgw, CompiledOn:Tue, 13 Mar 2012 02:24:46 GMT

59ee2ff6dbac2b6cd3e98cb0ff581bdb, WdExt.exe, 1.66MB, Trojan.Win32.Agent.hwgw, CompiledOn:Tue, 13 Mar 2012 02:24:49 GMT

f415ea8f2435d6c9656cc6525c65bd3c, wtmps.exe, 1.94MB, Trojan-Dropper.Win32.Daws.awfy, CompiledOn:Mon, 05 Mar 2012 08:37:55 GMT

Related MD5s, Domains, and Detections

Trojan.Win32.Agent.hwgw

78d3c8705f8baf7d34e6a6737d1cfa18, mscaps.exe

2d9df706d1857434fcaa014df70d1c66, arc.dll

1e7c6907b63c4a485e7616aa04351da7, @aedf66.tmp.exe

1fcc5b3ed6bc76d70cfa49d051e0dff6, dis.dll

523b4b169dde3bcab81311cfdee68e92, wdext.exe

541989816355fd606838260f5b49d931, wdext.exe

5e34f85278bf3504fc1b9a59d2e7479b, wdext.exe

6a9461f260ebb2556b8ae1d0ba93858a, sha.dll

78ba5b642df336009812a0b52827e1de, wdexe.exe

7f15d9149736966f1df03fc60e87b8ac, wdext.exe

7f3a38093bd60da04d0fa5f50867d24f

82206de94db9fb9413e7b90c2923d674

a59d9476cfe51597129d5aec64a8e422, @ae465f.tmp.exe

f1c9f4a1f92588aeb82be5d2d4c2c730, usd.dll

fffa05401511ad2a89283c52d0c86472, att.dll

d0c9ada173da923efabb53d5a9b28d54, fil.dll

Trojan-Dropper.Win32.Daws.awfy

2f7b96b196a1ebd7b4ab4a6e131aac58

8948f967b61fecf1017f620f51ab737d

…and almost 800 other executables that were infected on network shares and attached drives

c2 Domains

a.gwas.perl.sh,211.233.75.83

a-gwas-01.dyndns.org

a-gwas-01.slyip.net

Who’s Really Spreading through the Bright Star?