Introduction

The number of bootkits is steadily growing. All kinds of new bootkits are appearing: sophisticated and simple, serving different purposes (such as rootkits or ransomware Trojans). Malware writers are not above analyzing their competitors’ malicious code.

It is not easy to impress a malware expert with a new bootkit nowadays: boot-record infections have been studied sufficiently in-depth and plenty of information on the subject can be found online. However, this time we have come across an interesting specimen: the Xpaj file infector, complete with bootkit functionality and able to run both under Windows x86 and Windows x64. What makes it stand out is that it successfully runs on Windows x64 with PatchGuard enabled, using splicing in the kernel to protect the infected boot record from being read or modified.

In this paper, I analyze the rootkit’s operation under Windows 7 x64. It is not worth analyzing the rootkit’s operation under Windows x86, since the malware uses more or less the same algorithm in both operating system versions.

Test payload?

The following conclusions can be made from an analysis of the same Xpaj modification produced by our colleagues from Symantec:

- the Xpaj file infector does not infect 64-bit executable modules, including kernel-mode drivers, i.e. the virus infects only 32-bit executables (.exe and .dll);

- infected files do not have a self-replication mechanism;

- code injected from the kernel mode into a 64-bit application only displays a debug message and does not do anything else.

Based on the above conclusions and on infection statistics (see below), it can be conjectured that this variant of the virus is merely a test version. The next modification of the malware could be fully-functional and, who knows, perhaps its authors will implement a mechanism for infecting 64-bit executables, including kernel-mode drivers (which will of course involve disabling signature checking).

Loading

As usual, everything starts with an infected MBR. As in virtually all previous cases, the main purpose of the infected boot record is to read additional sectors and pass control to them.

The additional sectors at the end of the disk include modules that are loaded by the bootkit as required. All the modules, with the exception of the first one, are compressed using APLib.

The first module operates according to the following algorithm:

- read the original, uninfected MBR and write it to memory in place of the infected MBR;

- hook interrupt 13h, which is responsible for disk sector read and write operations;

- pass control to the original boot record.

Having passed control to the original MBR, the operating system will continue initializing. During initialization, the kernel file and the necessary components are read from the disk. In the interrupt hook, the bootkit waits for the kernel file to be read, calculating a checksum from the beginning of the file and checking some of the fields in the header.

To continue the initialization of the bootkit, the malware writers chose a method similar to that used in TDL-4, the difference being that this time the kernel file is selected as the target, rather than KDCOM.DLL. When it detects that the kernel file is being read, the bootkit saves the first 0x120 bytes from the beginning of the file and overwrites the header with its own code.

Figure 1. Modified kernel file header

Next, the bootkit finds an exported function named MmMapIoSpace and hooks it using splicing. The hook points to the code in the kernel file header.

Figure 2. MmMapIoSpace function hook

Here is what the function’s prototype looks like:

IN PHYSICAL_ADDRESS PhysicalAddress,

IN SIZE_T NumberOfBytes,

IN MEMORY_CACHING_TYPE CacheType

);

This function maps a physical address to the virtual memory. Don’t forget that the bootkit’s first module is still in the physical memory when this function is first called.

Further initialization of the bootkit takes place after the hooked function is called.

Figure 3. MmMapIoSpace call stack

When first called, the code in the kernel file’s header restores the stolen bytes of the MmMapIoSpace function and calls the original function, which maps the physical address of the bootkit’s first module (see Figure 1 and Figure 5) to virtual memory. Then control is passed to the mapped code.

Figure 5. Function call for the original MmMapIoSpace function and physical memory contents

The bootkit’s initialization continues by passing control to the mapped physical memory.

Subsequent operation is based on the following algorithm:

- restore the stolen 0x120 bytes at the beginning of the kernel file;

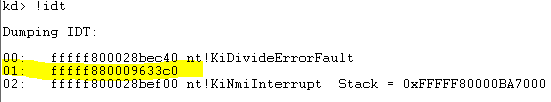

- hook interrupt INT 0x01 (KiDebugTrapOrFault) for each processor;

- find the exported function ZwLoadDriver by its hash;

- hook ZwLoadDriver using splicing;

- find the exported function NtReadFile by its hash;

- hook NtReadFile using splicing;

- find the exported function NtWriteFile by its hash;

- hook NtWriteFile using splicing;

- remove the interrupt hook from INT 0x01 (KiDebugTrapOrFault) from each processor;

- call MmMapIoSpace with the original parameters, i.e. pass control to the kernel for further initialization of the operating system.

Figure 7. KiDebugTrapOrFault hook

Figure 8. First stage of hooking ZwLoadDriver, NtReadFile and NtWriteFile

The bootkit’s further initialization is handled by the ZwLoadDriver function hook, since in the first stage of the bootkit’s operation the NtReadFile/NtWriteFile hooks are stubs which pass control to the original functions and do not do any other work.

Figure 9. Stub for the NtReadFile function

Obviously, this is a placeholder specially prepared to insert the working code for the NtReadFile/NtWriteFile hooks later.

When the ZwLoadDriver function is first called, the bootkit continues to initialize.

The ZwLoadDriver hook operates according to the following algorithm:

- open link “??physicaldrive0”;

- read sectors holding the third module from disk;

- unpack APLib;

- pass control to the third module’s entry point;

- call the original ZwLoadDriver.

This ends the first module’s operation and control is passed to the third module, which completes the bootkit’s initialization in the system.

Figure 10. The third module’s main functionality

The third module performs the following operations:

- loads various settings;

- sets up a callback function to be invoked when a process is created;

- sets up a callback function to be invoked when a module is loaded into memory;

- replaces the stubs of NtReadFile/NtWriteFile hooks with their functional versions.

Figure 11. Functional version of the NtReadFile hook

Compare the NtReadFile function hook in Figure 11 with the hook in Figure 9.

It is quite obvious that the NtReadFile/NtWriteFile hooks are needed to protect the bootkit’s critical areas from being read and modified.

Callback functions

Two callback functions are installed when the bootkit is initialized.

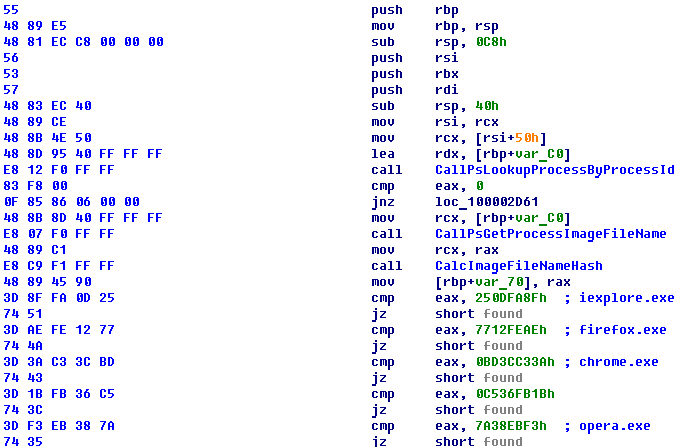

The first function terminates any antivirus processes. When the function is called during the creation of any process in the system, the bootkit calculates a checksum from the name of the process and compares it against its internal list of checksums.

Figure 12. Process name checksums

If a process name checksum matches a checksum on the bootkit’s list, the bootkit inserts a RET instruction in the process entry point and the process is terminated.

Figure 13. Process termination function

The second callback function is invoked by the bootkit when a module is loaded into the memory. It is used to inject code into various processes, including those of popular web browsers. Similar to the process termination function, this function calculates a checksum from the name of the process and checks it against an internal list of checksums.

Figure 14. Code injection function

What about PatchGuard?

Earlier, I mentioned a protection mechanism integrated into the kernel of the 64-bit Windows operating system. PatchGuard was created to prevent modifications to the kernel of the operating system and its critical structures, such as various service tables (SSDT, IDT, GDT), kernel objects and so on. The protection mechanism activates at an early stage of kernel initialization and scans the above structures over certain periods of time for the introduction of modifications. Should any modifications be identified, the system is deliberately crashed. This mechanism was primarily designed to protect against kernel-mode rootkits. However, there is a downside: many antivirus and security products use kernel-level intercepts for different, legitimate purposes, including pro-active protection modules.

Arguments over this matter still persist between antivirus vendors and Microsoft. Some maintain that antivirus companies should not use undocumented hooks within the system kernel, so other methods must be used to stop the penetration of malicious code into the kernel. Others think that Microsoft is failing to deliver the required security level, and these hooks are essential to enhance the security of the OS. A further group argues that the system cannot be trusted once malicious code penetrates into its kernel, and there is no use in treating such systems. All of these points of view have some merit, so I will not dwell further on the issue.

Any protection tool can be hacked or bypassed one way or another. PatchGuard is no exception. This mechanism was closely examined by both third-party researchers and cybercriminals, and several bypass methods were invented. For instance, TDL-4 uses a conceptual method, in which the rootkit’s hook spot is simply ignored by the protection mechanism. Other methods also exist, including those based on modifying the loader and the file of the operating system’s kernel; all these are designed to disable the initialization of PatchGuard. Yet another method is based on modifying an initialized kernel; it disables the launch of the scan mechanism. Also, PatchGuard will not initialize if the kernel debugger is enabled while the operating system is booting – this feature was built in so the developers could use breakpoints to test and debug their drivers.

Xpaj is interesting in that it uses yet another conceptual method to bypass PatchGuard. The thing about PatchGuard is that it initializes at a fairly late stage of booting the operating system. Since Xpaj is a bootkit, it can control any stage of booting the operating system and modify the kernel before the protection mechanism is initialized. At the time the kernel is initialized, it already contains all modifications and hooks Xpaj has introduced, so PatchGuard starts protecting these modifications rather than detecting them.

To confirm that PatchGuard does indeed protect the ZwLoadDriver/NtReadFile/NtWriteFile hooks, I carried out a small experiment. I started an infected system in the debug mode, waited for it to boot, enabled the kernel debugger and restored the modified bytes in one of the hooked functions. After a while, the system crashed – PatchGuard detected kernel modifications in the memory and called BSOD.

Figure 15. System crash after a hooked function is restored.

There’s no real need for any further commentary.

Statistics

I used KSN, our cloud service, to collect statistics on detected Xpaj boot record infections and on detections of the malicious program’s installer. The most useful data that can be derived from these statistics includes the bootkit’s geographical distribution and of course infected operating system versions.

Figure 16. Installer geographical distribution

Figure 17. Infected MBR geographical distribution

Figure 18. Infected operating systemstatistics

Conclusion

In 2008, we saw an old technology, MBR infection, return to the scene. Since then, plenty of time has passed. Today’s bootkits represent the modern trend of ‘rootkit building’. This mechanism is set to remain in the cybercriminal arsenal for the foreseeable future.

Infecting the boot record is a very convenient method of initializing malicious code as early as possible. On top of everything else, it offers enormous possibilities in terms of controlling operating system startup.

The Windows x64 family of operating systems has become very widespread, and malware writers are trying to make their malicious programs more versatile in order to maintain a high rate of infections.

Microsoft has introduced some restrictions and new technologies for Windows x64 designed to combat rootkits. However, in practice neither the requirement that kernel-mode drivers should be signed with valid signatures, nor the PatchGuard mechanism have succeeded in rectifying the overall situation. There have been and will be rootkits designed for 64-bit operating systems, and their number continues to grow.

XPAJ: Reversing a Windows x64 Bootkit