Introduction

It’s almost a year since the publication of Part 4 of Mobile Malware Evolution. At that time, we made several predictions about the development of threats targeting mobile platforms in 2011. Let us take a look to see if they were right.

In brief, we predicted:

- SMS Trojans would be dominant.

- The number of threats targeting Android would increase.

- The number of vulnerabilities found in different mobile platforms would increase, and their use in attacks could increase.

- The amount of spyware would increase.

Now, in early 2012, we can see that our predictions have, unfortunately, all been correct.

- SMS Trojans are actively being developed.

- The number of threats for Android is growing significantly.

- Malicious users are aggressively exploiting vulnerabilities.

- Spyware is now causing a host of problems for mobile device users.

We also need to note that the dominance of malicious programs targeting the J2ME platform has come to a definitive end. This was primarily due to the fact that virus writers have shifted their focus to the Android platform. As a result of the popularity of this platform, virus writers now face a number of additional problems that will be addressed below.

Overall, in 2011 malicious programs reached a new qualitative level — simply speaking, they became more complex. Yet most mobile threats are still less sophisticated than the originals produced by Russian and Chinese virus writers, and that isn’t likely to change any time soon.

This edition of Mobile Malware Evolution (Part 5) will cover these and other developments.

Statistics

Following the format of previous editions, we’ll start with some statistics.

The number of families and modifications

Readers may remember that by late 2010 our collection had a total of 153 families and over 1,000 modifications of mobile threats. Furthermore, the 2010 detection rate for new malicious programs targeting mobile devices was up 65.12% on the previous year.

The number of modifications and families of mobile malicious programs in Kaspersky Lab’s records as of 1 January 2012 is shown in the table below.

| Platform | Modifications | Families |

| Android | 4139 | 126 |

| J2ME | 1682 | 63 |

| Symbian | 435 | 111 |

| Windows Mobile | 81 | 23 |

| Others | 19 | 8 |

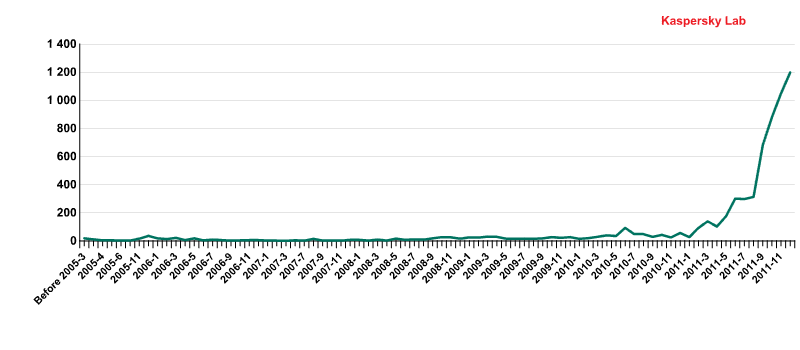

By how much did the number of threats rise in 2011? Over the course of 2011, we recorded 5,255 new modifications of mobile threats and 178 new families! Moreover, the total number of threats over just one year increased 6.4 times. In December 2011 alone we uncovered more new malicious programs targeting mobile devices than over the entire 2004-2010 period.

The number of new modifications of mobile threats by month, 2004-2011

The diagram clearly shows a sharp surge in the number of new threats during the last six months of 2011. We have not seen anything like this in the entire history of mobile threats.

Behaviors

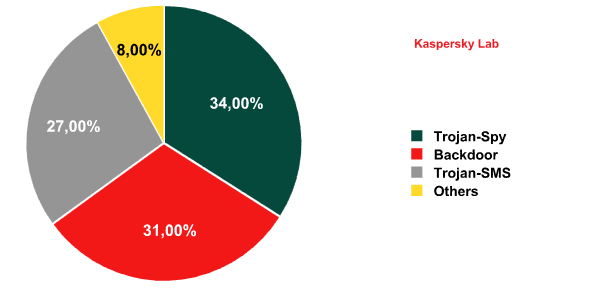

Previously, we shared statistics for mobile threats by behavior. However, Kaspersky Lab’s data for 2011 is rather unusual.

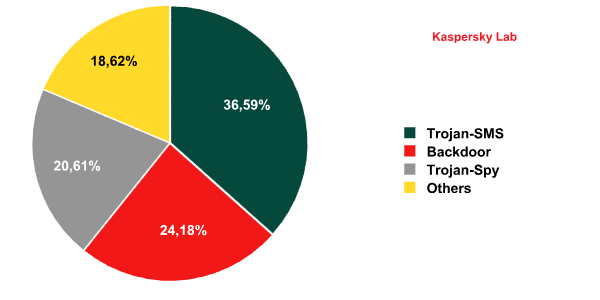

The distribution of malicious programs targeting mobile devices by behavior in 2011

As we noted above, in 2011, not only did the number of mobile threats rise drastically, but we also saw some qualitative changes take place among threats. While SMS Trojans are still the dominant behavior among all detected mobile threats, making easy money for malicious users, their share of all mobile threats has fallen from 44.2% in 2010 to 36.6% in 2011.

Backdoors represent the second most prevalent behavior. In 2010, malicious users barely gave this behavior a second glance. The surge in interest in backdoors has been sparked by virus writers’ growing interest in the Android OS, and the overwhelming majority of detected mobile backdoors target Android smartphones. All too frequently, a backdoor will be bundled with a root exploit, and if the device is infected, the malicious user will take full control of the mobile device.

The third most common mobile threat behavior is spyware. These programs steal personal user data and/or data about the infected mobile device. Our prediction of the development of a threat that will try to steal everything has turned out to be correct for mobile devices as well: in 2011, virus writers actively created and spread these types of malicious programs.

Platforms

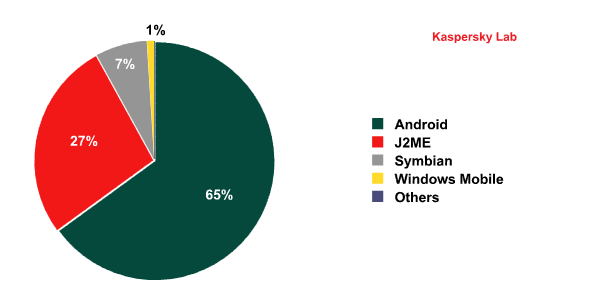

If we look at the distribution of mobile threats by platform, then — as we mentioned above — J2ME is no longer the top targeted operating system among mobile threats.

The distribution of mobile threats by platform in 2011

The reason the J2ME platform is no longer the main target is clear: the number of mobile devices running on the Android operating system has risen considerably. The same thing happened with Symbian a while back. In 2004-2006, Symbian was indisputably the platform most frequently targeted by virus writers. However, it was pushed out by J2ME, as threats for that platform were able to reach a greater number of mobile devices. Today, Android is the world’s most widespread operating system for mobile devices, which is why so many new threats have been developed for this platform. According to various estimates, the Android operating system runs on 40-50% of all smartphones.

A steady rise in the number of threats targeting Android was observed during the last six months of 2011. By approximately mid-summer, the number of malicious programs for Android had surpassed the number of threats targeting Symbian, and by autumn, it had left J2ME behind as well. By the end of the year Android was the undisputed leader among the targeted platforms– and that probably won’t be changing any time soon.

Android under attack

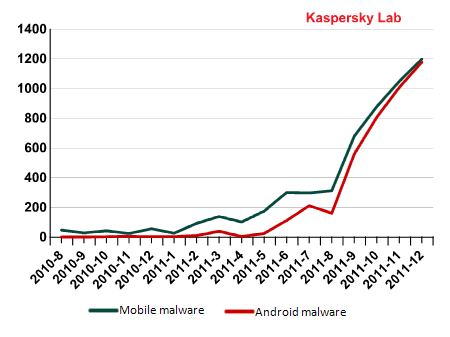

The explosive growth in the number of malicious programs for all mobile platforms was driven by the surge in the number of threats targeting Android.

The number of new modifications of all mobile threats, and threats targeting Android, by month in 2011

The chart above illustrates that in the second half of the year, when the number of new malicious programs targeting mobile devices began to grow at a faster rate, most of the threats detected each month were aimed at the Android platform. The table below sets out the situation in absolute terms.

| Month | Total number of new modifications |

Number of new modifications targeting Android |

| 2011-1 | 27 | 4 |

| 2011-2 | 93 | 11 |

| 2011-3 | 139 | 39 |

| 2011-4 | 102 | 5 |

| 2011-5 | 175 | 25 |

| 2011-6 | 301 | 112 |

| 2011-7 | 298 | 212 |

| 2011-8 | 313 | 161 |

| 2011-9 | 680 | 559 |

| 2011-10 | 879 | 808 |

| 2011-11 | 1049 | 1008 |

| 2011-12 | 1199 | 1179 |

All of the mobile malware for Android that Kaspersky Lab has detected can be divided into two major groups:

- threats designed to steal money or data;

- threats designed to take control of the infected device.

The distribution of behaviors among malicious programs targeting the Android platform

Objective: steal data or money

As early as October 2011, one third of the threats targeting Android were designed to steal personal data from a user’s device in one way or another (be it contacts, the call log, text messages, GPS coordinates, photos, etc.).

Chinese cybercriminals are the front-runners when it comes to stealing data. What’s more, they are typically most interested in information about the device itself (the IMEI and IMSI, the country, the telephone number itself) rather than the owner’s personal and confidential information.

The Nickspy Trojan (Trojan-Spy.AndroidOS.Nickspy) is probably the exception to the rule here. This threat is capable of recording all of the owner’s conversations on the infected device on audio files and then uploading those files to a remote server controlled by malicious users. One of the Nickspy modifications disguises itself as a Google+ app and can accept incoming calls from the telephone numbers of malicious users unnoticed (the numbers are written into the malicious program’s configuration file). When an infected phone accepts a call like this without the owner noticing, the malicious user can then hear everything happening near the infected device, including the conversations held by the device’s owner. This Trojan is also interested in text messages, call data, and the device’s GPS coordinates. All of this data is also sent to remote servers run by malicious users.

While Nickspy hails from China, Antammi (Trojan-Spy.AndroidOS.Antammi) was created by Russian virus writers. Antammi’s “cover” is a legitimate, functioning app for downloading ringtones. The Trojan can steal just about all of a user’s personal data: contacts, the text message archive, GPS coordinates, photos, and more. It has also been used to send its activity logs to cyber criminals by email, and to upload the data onto their servers.

One major story ought to be mentioned in this section. In mid-November, the researcher and blogger Trevor Eckhart published an article based on open-source documents. He explained that some US-based cellular providers, as well as smartphone manufacturers, are pre-installing software developed by CarrierIQ on mobile devices sold in the US. This software collects a range of information about the smartphone itself, its operations, and is also capable of saving data about the keys pressed by the user and the websites he visits. In other words, the CarrierIQ program collects quite a bit of personal information about a smartphone’s owner.

Researchers and the media began to take a close look at Android phones, specifically those made by HTC. It was also reported that software from CarrierIQ is supported on Blackberry and Nokia phones, although both companies have issued official statements denying those allegations and stating that they have never pre-installed the software on their devices. Apple, however, has stated the opposite. CarrierIQ’s development has been pre-installed on devices produced by the company, although since the release of iOS5 it is no longer used on any devices, apart from iPhone4. In November 2011, iPhone 4 users received CarrierIQ even with iOS5, but according to Apple’s statement, it should have been removed in subsequent system updates.

After this story sent shockwaves through the media, CarrierIQ issued a statement, in which it explained why its software collects information not only about a device and its operations (for example, the battery and its charge, the presence of a WiFi connection), but also keylogging data and website addresses. According to CarrierIQ’s assurances, all of this is meant to serve as diagnostic information for cellular providers. In other words, the program sends data about access problems with Facebook, but not Facebook content itself. The company also stated that the data is sent directly to the cellular providers, which are their clients.

One important question remains: why are users essentially unable to opt out of having this “assistance in collecting diagnostic data” on their phone?

Today, the problems surrounding the protection of personal data is more pressing than ever before. Similar discoveries only provoke more interest in the subject. Isn’t it likely that this situation will lead to the discovery of more cases where this type of software has been pre-installed by other cellular providers and manufacturers?

As regards mobile threats used to steal money, Russian virus writers are still on the frontline. They have begun to create SMS Trojans for Android en masse. New affiliate programs are emerging and making it possible to automatically general a variety of SMS Trojans and offer a selection of tools and options for proliferating them (fake storefront apps, QR codes, scripts, domain parking, etc.). We address this problem in more detail below.

Objective: device control

Threats designed to control a device became very common in 2011. Today, backdoors are edging ahead of Trojan spyware targeting Android.

Chinese virus writers have been engaged in the non-stop production of backdoors. Incidentally, most of these backdoors contain exploits, the sole purpose of which is to execute the device’s root (i.e., gain super-user privileges or obtain maximum privileges on the device). This allows a malicious user to obtain full remote control over the entire smartphone. In other words, after infection and execution of the exploit, a malicious user can remotely execute just about any action via smartphones.

It is the root exploits for Android that started the mass use exploitation of vulnerabilities in mobile operating systems, and they are the go-to choice for Chinese virus writers. Furthermore, most of the exploits that are being used have been around for a long time and are for outmoded versions of the Android system. However, since most users rarely update their systems, many users could still potentially be victims of cyber criminals.

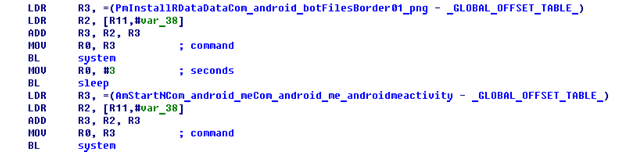

Perhaps the best (and most serious in terms of functions) example of a backdoor was detected at the very start of 2012 on the RIC bot: Backdoor.Linux.Foncy. This backdoor was in APK Dropper (Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Foncy), which — in addition to the backdoor — also had an exploit (Exploit.Linux.Lotoor.ac) in order to gain root rights on the smartphone and an SMS Trojan (Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Foncy).

The dropper copies the exploit, IRC bot, and SMS Trojan into a new directory (/data/data/com.android.bot/files), and then launches the root exploit. If the exploit runs successfully, it will then launch the backdoor, which goes on to install the Foncy SMS Trojan (which we will address in more detail in the section on SMS Trojans). To be clear, the backdoor has to install and launch the APK file of the SMS Trojan; until then, the dropper just copies the Trojan into the system:

The Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Foncy installation process

After launching the SMS Trojan, the backdoor attempts to connect with a remote IRC server on the #andros channel using a random username. After that, it can accept any shell commands from the server and execute them on the infected device.

Malware on the Android Market

Malicious programs available on the official Android Market became yet another headache in 2011. The first such incident was recorded in early March 2011, after which threats began to appear on the Android Market on a regular basis. The popularity of the Android platform and the simplicity of developing software for the OS, combined with the ability to share it via an official source without an effective threat analysis system turned Google’s Market into something of a sick joke. Malicious users were sure to take advantage of all of these factors, and as a result, we encountered a situation where threats were being spread via the Android Market not just for a few hours or days but over the course of weeks and even months, leading to a large number of infections.

SMS Trojans

In 2011, the way in which the most prevalent behavior among mobile threats developed underwent some changes. For starters, SMS Trojans ceased to be the exclusive problem of Russian-speaking users. Second, the attacks against Russian users grew exponentially. And finally, the J2ME platform was phased out as the main environment for SMS Trojans.

Over the first half of 2011, SMS Trojans continued to be dominant among the other types of mobile threat behaviors. Only by the end of the year did the gap begin to close somewhat, due to the non-stop activities of Chinese virus writers producing backdoors and spyware Trojans.

In early 2011, many mobile device users were inundated with regular text messages informing them that they had won an MMS gift from a certain Katya. It’s no surprise that when attempts were made to download this “present”, users received a JAR file that was actually an SMS Trojan. Nearly all of the malicious programs detected by Kaspersky Lab were from the Trojan-SMS.J2ME.Smmer family. These Trojans are relatively primitive in terms of their functions, but considering the enormous scale and frequency at which they were sent out, the simplicity of the threat did not prevent malicious users infecting a large number of mobile devices. The scale of these mailings was considerably larger than prior attacks. The mobile phones of tens of thousands of users were regularly subjected to the risk of infection.

In 2008, 2009, and 2010, the main platform targeted by SMS Trojans was J2ME. In 2011, a change took place, and now most SMS Trojans are designed to target the Android platform. The new Trojans are essentially the same as their J2ME counterparts. The methods used to disguise them are the same — usually an imitation of a legitimate app, such as Opera or JIMM. They also spread the same way that J2ME Trojans spread, typically with assistance from affiliate programs. Usually, one and the same affiliate will specialize in J2ME threats and malware targeting Android.

Before 2011, SMS Trojans were primarily aimed at users from Russia, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan. But in 2011, Chinese virus writers began to create and spread SMS Trojans as well. However, Chinese virus writers tended not to develop malicious programs which function solely as an SMS Trojan. Sending out text messages to paid numbers is now an “extra feature” that’s bundled with other Chinese threats.

Kaspersky Lab also recorded the first attacks aimed at users in Europe and North America. One of the first to cross the borders was the GGTracker Trojan, which is aimed at US-based users. The program is disguised as a utility that will reduce a smartphone’s battery use, although in fact it actually subscribes the user to a paid service via text messaging.

The Foncy family of SMS Trojans is yet another shining example. Despite its primitive functions, Foncy became the first threat targeting users in Western Europe and Canada. Later on, its modifications attacked users in Western Europe, Canada, the US, Sierra Leone, and Morocco. Moreover, based on some of its features, we can conclude that the authors of this malicious program are not based in Russia.

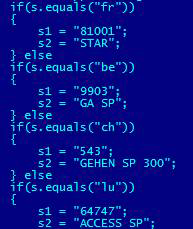

The Foncy Trojan has two specific features. First, it integrates easily. The threat is able to determine the country of the infected device from the SIM card, and depending on the country, it will select an appropriate area code and number to where text messages will be sent.

An incomplete list of the short numbers for different countries in the body of the Foncy Trojan

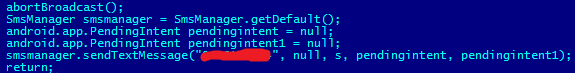

Second, the Trojan sends a report about its activity to malicious users. As a rule, the Trojan sends a text message to a paid number without the user knowing. This message buys certain services. This might include access to a website or archive, a subscription to a mailing list from a website, etc. In response, a text message is received to confirm payment, and the malicious program hides this confirmation from the user. Foncy resends the text of these confirmation texts and the short numbers from which they came to the Trojan’s owners. At first, this information was simply forwarded by text message to malicious users. Subsequent modifications of the Trojan have uploaded the data directly to their servers.

Forwarding certain incoming text messages

This is clearly how malicious users obtain information about the number of paid text messages that are sent and the number of Foncy-infected devices.

Man-in-the-M(iddle)obile

The first attack using Man-in-the-Mobile technology took place in 2010. However, these attacks were developed primarily in 2011, when we saw the emergence of a version of threats such as ZitMo and SpitMo for different platforms (ZitMo for Windows Mobile, and ZitMo and SpitMo that both target Android) and malicious users continued to improve the functions of their programs.

The ZitMo (ZeuS-in-the-Mobile) and SpitMo (SpyEye-in-the-Mobile) Trojans work in connection with the regular ZeuS and SpyEye programs and are some of the most complex mobile threats detected recently. Their features include:

- Working as a team of two. ZitMo or SpitMo by themselves are your typical spyware programs capable of sending text messages. However, when they are used together with “classic” ZeuS or SpyEye, malicious users are able to overcome security barriers protecting users against mTAN bank transactions.

- A narrow field of specialization: forwarding incoming messages with mTAN to malicious users or to their servers. The mTAN codes are then used by cyber criminals to confirm financial operations using hacked bank accounts.

- They exist for numerous platforms. Versions of ZitMo have been found for Symbian, Windows Mobile, Blackberry and Android, while SpitMo has been found for Symbian and Android.

Perhaps among the most critical events of the past year was the confirmation of the existence of ZitMo for Blackberry and the emergence of a ZitMo and SpitMo version for Android. The appearance of ZitMo and SpitMo for Android is especially interesting, since the authors of these threats seemed to have passed over the most popular mobile platform for a relatively long time.

Attacks using ZitMo, SpitMo, and similar threats will continue in the future and attempt to steal mTANs (or perhaps other secret data transferred by text message). However, more likely than not, these attacks will become more targeted and will begin to hit a wider number of victims.

QR codes: a new way to spread threats

QR codes are becoming more prevalent and widely used in a variety of advertising, badges, and other things to provide fast, simple access to specific information. That is why the first attacks using QR codes did not come as a huge surprise.

Today, people who use smartphones often look for software for their devices using a regular computer. In these cases, the user must manually enter a URL in their mobile device’s browser. This can be very inconvenient, so websites that offer apps for smartphones typically have QR codes.

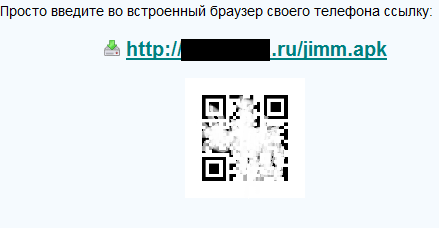

Many malicious programs for mobile devices (and especially SMS Trojans) are spread on websites were all of the software is malicious. On these sites, in addition to direct links leading to threats, cyber criminals have also started to use malicious QR codes with an encrypted link to the same malware.

The first attempt to use this technology was made by Russian cyber criminals who hid SMS Trojans for Android and J2ME in QR codes.

An example of a malicious QR code

(“Just enter the following link into your phone’s browser”)

Fortunately, attacks that use QR codes are still rare. However, the growing prevalence of this technology among users means that it is likely to become just as common among malicious users. Furthermore, malicious QR codes are used not only by virus writers (or groups of virus writers) but are becoming more common among the infamous affiliate programs, which will soon ensure that they become popular among cyber criminals.

Mobile hacktivism: the beginning

Over the course of 2011, Kaspersky Lab observed a previously unseen surge in computer-based activity among malicious users whose main goal was not to generate cash, but to protest or even get revenge against politiciains, government agencies, large corporations, and countries. Politically motivated hackers have penetrated even the most secure systems and have published the data of hundreds of thousands of people around the world. Even the most technologically advanced systems have found themselves the victims of DDoS attacks from major hacktivist botnets.

Hacktivism also includes malicious programs that are designed with a clear political motive. This type of malware has emerged in the mobile world.

The threats detected by Kaspersky Lab, such as Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Arspam, are targeted at users in Arab countries. This ‘Trojan-ified’ compass app was spread in Arabic-speaking forums. The Trojan’s main function is to send text mesesages with a link to a forum dedicated to Mohamed Bouazizi to randomly selected contacts on the infected device. (Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in Tunisia, sparking mass riots which then turned into a revolution.)

Furthermore, Arspam also attempts to determine the ISO code of the country in which the smartphone is being used. If the code is BN (Bahrain), then the malware attempts to download a PDF containing a report from the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry (BICI) on the violation of civil rights.

At this point in time, this appears to be the only example of mobile hacktivism – but it is likely that we will encounter some others in 2012.

Conclusion

To summarize the past year, we can say with confidence that it was one of the most critical so far for the evolution of mobile threats. First of all, this was because of the steady growth in the number of malicious programs targeting mobile devices. Second, because malicious users moved to Android as their main targeted platform. Finally, because 2011 was the year in which malicious users essentially automated the production and proliferation of mobile threats.

What’s waiting for us in 2012? In brief, we expect to see the following:

- Interest in Android OS will continue to rise among mobile virus writers, whose efforts will be focused primarily on creating malicious programs that target this specific platform.

- A rise in the number of attacks using vulnerabilities. Today, exploits are used only to obtain root access on a smartphone, but in 2012 we can expect the first attacks where exploits are used to infect the mobile operating system.

- An increase in the number of incidents involving malicious programs found in official app stores, primarily Android Market.

- The first mass worms for Android.

- The spread of mobile espionage.

Mobile Malware Evolution, Part 5